1. Background

Economic crises often lead companies to reduce their investment in innovation, resulting in increased scientific and cultural dependency (1). These crises have a significant impact on societies, one of which is their effect on the education system (2). The Greek medical education system has been one of the biggest victims of the economic crisis in the country. The government's failure to fulfill its financial obligations, especially regarding joint projects with universities, has affected medical schools, weakened the medical profession, and jeopardized high-quality research (3). The impact of economic crises and reduced budgets for medical schools in the 1970s also weakened and threatened the medical profession (4). In 2018, the US National Academy of Sciences stated that the difficulty in financing medical students, particularly for Black men, can present both a financial and psychological barrier to pursuing this field (5).

One of the most severe and serious economic crises a society can face is economic sanctions. Article 41 of the United Nations Charter states: "The Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of armed force are to be taken to give effect to its decisions; and it may call upon the members of the United Nations to apply such measures. These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations." However, as shown by the impact of economic sanctions on Cuba, Haiti, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Syria, and Iran, economic sanctions are considered one of the greatest social disasters (6). Sanctions can often have a more devastating impact on people in a sanctioned country than wars (7). Moini's estimate of the financial consequences of economic sanctions in Iran revealed that the costs to society from the decrease in income following the sanctions amounted to about 18% of the gross domestic product (8). Mahrabi argued that economic sanctions have negatively affected the quality of healthcare and child health and can have numerous other adverse consequences (9). Moini also believes that the negative effects of economic sanctions on education will not be recoverable, even after the sanctions are lifted (8). Teaching and public education in many countries worldwide have come under severe pressure due to international sanctions (10).

To produce science and provide up-to-date and effective services to the public, medical universities need to be connected with global research communities. In Sudan, the isolation of academics has led to organizations becoming reluctant to collaborate with them in research or publish articles (11).

Recently, the renowned publisher Elsevier asked its American editors and reviewers not to publish manuscripts authored by Iranian researchers who are affiliated with the Iranian government (12). Dehghani et al. highlighted one of the effects of economic sanctions as a disruption in international research collaborations and activities, leading to an increase in stress and workload for the medical community (13). Tabrizi cites economic sanctions as the reason for the university's inability to procure modern and essential hospital equipment, stating that this poses a barrier to education: “Currently, public hospitals are facing many problems in providing equipment, which indirectly affects the educational and training programs for residents in large areas of Iran. Many surgeries are not being performed, and the necessary training equipment is not available, putting educational programs at risk” (14). The results of studies conducted indicate the destruction of various systems, including educational systems, as a result of economic crises. However, whether economic sanctions can harm education, particularly medical education, requires further investigation.

2. Objectives

This research was designed to address the question of whether economic sanctions can affect medical education.

3. Methods and Results

This review is a narrative review. Narrative reviews allow the authors to describe their findings on a specific topic while critically evaluating and analyzing existing literature (15). The present research was conducted to answer the question: What is the impact of economic sanctions on the Iranian medical science education system?

In the extensive initial research conducted on the topic, it was determined that the existing literature regarding the effects of economic sanctions on education primarily pertains to the years after 1995. Notable researchers, such as Garfield, typically investigate and publish the effects of economic sanctions on societies several years later. This led us to continue our search for studies published in Persian or English in both Iranian and international scientific journals from 1995 to 2023.

The search for English-language articles involved the following electronic sources and databases: EMBASE, Ovid, PubMed, PsycINFO, ERIC, Medline, and Google and Google Scholar search engines. The following keywords and their combinations were used: Economic sanctions, medical education, sanctions, and education.

The search for Persian-language articles involved using the following keywords: Sanctions, economic sanctions, medical education, and education. The databases searched for this purpose included SID, Magiran, IranMedex, and Google and Google Scholar search engines. These keywords were initially used individually, followed by the use of search operators (AND, OR) and possible combinations of the keywords to ensure a comprehensive search.

The steps taken in this review included systematic searching, article screening, quality assessment, and content extraction. To be included in the review, studies had to: Be published in Persian or English, be available in full text, and include the keywords or their equivalents in the title or abstract. Articles presented in proceedings or conferences, letters to the editor, or publications in non-scholarly outlets were excluded from the study.

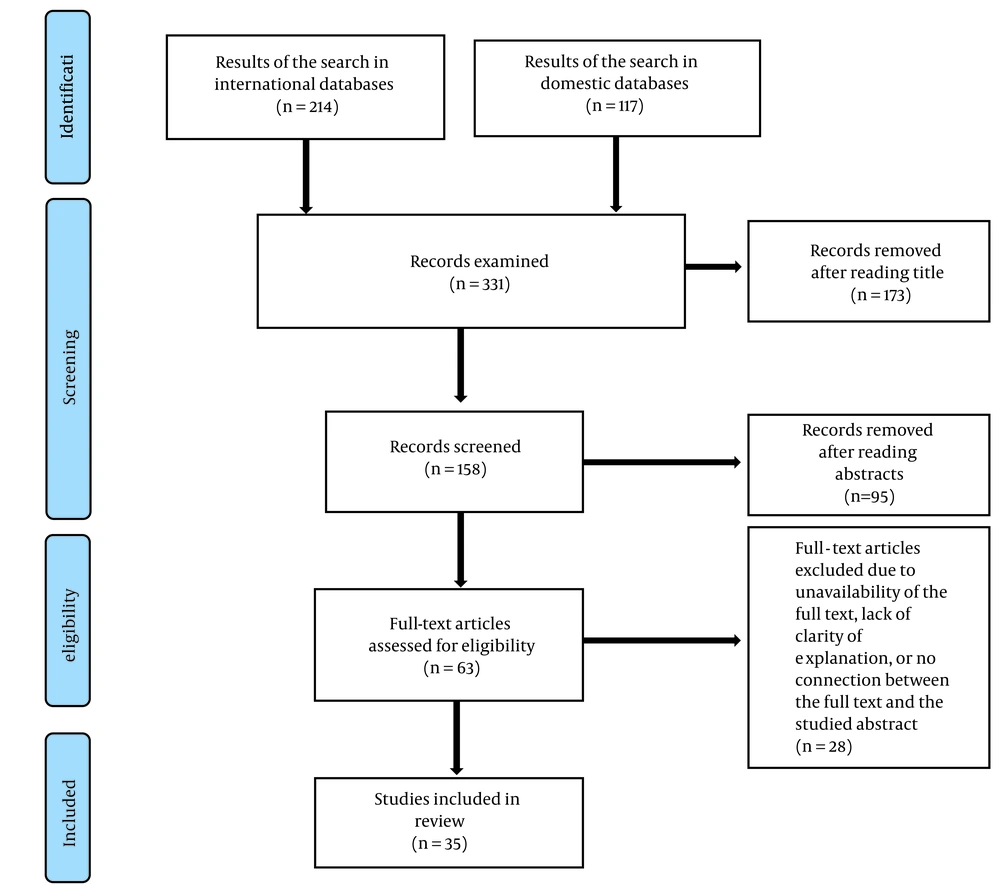

To increase the validity of the study and minimize potential biases, the quality of the collected articles was assessed by the research team (16). The result of the search in English and Persian databases yielded 214 and 117 articles, respectively. In the initial screening, which involved examining the titles, 173 unrelated articles were removed, leaving 158 articles for the abstract screening stage. In this stage, 95 unrelated articles were removed, and after accessing and reviewing the full text of the remaining 63 articles, 35 were ultimately qualified for review. The process of selecting articles based on the PRISMA diagram for narrative review studies (17) is shown in Figure 1.

3.1. Brief History of Sanctions

In ancient times, if an invading army was unable to conquer a city, it would block the supply of resources needed by the inhabitants by besieging the city (18). Sanctions have long been an important tool in international relations. For example, in ancient Greece, Pericles imposed a trade embargo against Megara in 432 BC after Megara’s invasion of Greek territory and the kidnapping of three Greek women from Athens, which ultimately contributed to the start of the Peloponnesian War (19).

The history of modern sanctions dates back to "Captain Charles Boycott" in Ireland in the late 1870s. During this time, Captain Boycott was economically and socially isolated by the Irish Land League due to his harsh treatment of farmers. Over time, the term "boycott" was extended to the international arena (20). After the First World War, there was growing attention to the idea that economic sanctions could replace armed hostilities as an independent policy tool (21). Some refer to the era after the Cold War as the "era of sanctions." Since 1990, several sanction regimes have been approved by the UN Security Council. Notable cases include sanctions against Iraq (1990), the former Yugoslavia (1991), the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992), Libya (1992), Syria (2011), and Iran (2012) (22).

Sanctions, as they are known today, have only been used since the 1930s. In 1935, the League of Nations organized a boycott or embargo against Italy for its invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). A few years later, in 1940, the United States imposed trade sanctions on Japan, seizing Japanese assets in the U.S. and embargoing its oil industry. In 1945, sanctions were incorporated into the UN Charter, with responsibility for ratification and oversight delegated to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). In 1990, the UN approved sanctions against Iraq in response to Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait (23).

In 1993, one of the few sanctions ever imposed against a country's senior leadership was applied to Iran. U. S. sanctions programs increasingly targeted Iran during the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama. In 2017, President Donald J. Trump signed executive order (E. O.) 13818. Since December 2017, the United States has used this authority to target more than 100 individuals and entities (24).

3.2. Economic Sanctions

International economic sanctions have been used as an alternative to military conflicts since the end of the Cold War (25). Economic sanctions are defined as the "deliberate withdrawal or threat of withdrawal from conventional, commercial, or financial relations." They are sometimes referred to as economic warfare (21). In principle, any restriction imposed by the sending country on the international trade and investment of the target country to force a policy change is considered an economic sanction (26). Lowenfeld defines economic sanctions as: "An economic—as contrasted with diplomatic or military—measure taken to express disapproval of the actions of the target or to induce that target to change some policies, practices, or even its governmental structure" (27).

Economic sanctions can take various forms, including commercial blockades and restrictions on financial transactions. They include the following types:

(a) Tariffs: Compulsory taxes on products imported from other countries;

(b) Quotas: Limits on the amount of goods imported or exported to another country;

(c) Embargoes: Trade restrictions that prohibit trade with a country.

Economic sanctions have been imposed on many countries (28). The penalties associated with economic sanctions usually affect a country’s imports, exports, assets, finances, and economic aid (6).

3.3. Effectiveness of Sanctions

The effectiveness of sanctions as a punitive measure is a subject of ongoing debate, with differing views on their impact (29). Some researchers believe that economic sanctions are effective in achieving their goals. Several studies claim that sanctions can be a suitable and successful alternative or complement to military force. For example, Rogers (1996) argues that the effect of international economic sanctions, particularly on academic life and education, is greater than many analysts suggest. However, the results of these studies are often met with skepticism and are open to debate (9).

Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliott's optimistic view of sanctions is that they succeed in only about one-third of cases, while Pape believes they succeed in at most 5% of cases. In the context of economic sanctions, categorizing the sanctioning parties as "winners" or "losers" is misleading because both parties can be harmed, and the consequences of sanctions may not align with the initial expectations (30).

One of the issues raised regarding the application of sanctions is their costs. Sanctions are intended to deprive the target country of some trade benefits and disrupt its economic interactions. The sanctioning country will also experience negative effects on its economic integration with the target country (31). In 1978, Strack stated that the Rhodesian sanctions not only failed to achieve their political goals but also undermined the situation they were intended to improve. One year later, Losman acknowledged that no political success had been achieved despite the detrimental economic effects caused by the Rhodesian sanctions (22).

Hufbauer et al. argue that sanctions are often unsuccessful in changing the behavior of foreign countries for the following reasons: (a) The imposed sanctions may be insufficient; (b) sanctions may create their own countermeasures (economic sanctions, in particular, may prompt the target country to support its government and seek alternative trade partners); (c) sanctions may prompt powerful or wealthy allies of the target country to support it and compensate for the deprivation caused by the sanctions; and finally, (d) the business interests of companies in the sanctioning country and its allies abroad may lead them to find ways to evade sanctions (23). A Gallup and Blame in December 2012 showed that although sanctions on Iran had significantly escalated the hardships and negative conditions in the lives of Iranian people, they had failed to significantly weaken public support for the government (32).

However, recent research goes beyond examining the effectiveness of sanctions and looks at the broader consequences of economic sanctions on the target country. The outcome of economic sanctions is the deprivation of the people in the targeted society of their basic human, health, and education rights.

3.4. The Effect of Sanctions on Education and Medical Education

Article 16 of the UN Charter, which allows the UN Security Council to impose economic sanctions against certain countries, stands in clear contradiction to Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being, including food... (and) medical care." After economic sanctions are imposed on a country, many vital drugs and medications may become unavailable. This silent massacre often goes unnoticed, or perhaps it is intentionally ignored (18).

One of the often neglected areas affected by sanctions is academic education and research systems. Sanctions create "invisible obstacles" to research in target countries by limiting access to necessary resources and restricting their effective use (33). In Zimbabwe, for example, after the imposition of economic sanctions, teachers resorted to teaching in informal schools to earn a living, as their living conditions had already been worsened. By January 2009, only six percent of rural schools in Zimbabwe were open, and thousands of educational institutions were established by individuals and businessmen without permission from the relevant ministry. The European Union's sanctions in 2002, along with other factors, exacerbated Zimbabwe's economic problems and had a major impact on the country's education system. Approximately 94 percent of public schools in rural Zimbabwe were closed until January 2009. The government's justification for closing schools was its failure to fund public schools due to economic sanctions, depriving part of the population—particularly poor children—of the opportunity to study. As a result, education in Zimbabwe gradually became accessible only to the wealthy (34).

In Haiti, gasoline sanctions from 1991 to 1994 led to the closure of schools and a reduction in the number of school days, with most schools operating only three days a week. Gross school enrollment declined from 83% in 1990 to 57% in 1994. Many families had to send their children to school in shifts. The pass rate for master's degree exams dropped from 43% in 1991 to 29% in 1997 (14). The sanctions imposed on Sudan also had a negative impact on various fields of educational activities (35).

Iraq’s education system was once one of the best in the Arab world before the sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council in August 1990. However, this system suffered serious damage due to the sanctions followed by the war. These sanctions rendered the Iraqi education system incapable of serving the people, and even future generations of children who would go to school and university students would inherit an educational system with significant flaws (36). The physical destruction of Iraq’s infrastructure worsened public health, but the true magnitude of the negative effects of the economic sanctions goes beyond their impact on public health. In fact, the lasting negative effects of these sanctions, such as Iraqi children falling behind in their academic trajectory and disruptions in their education, will continue for years to come (37). Stressful factors, including economic sanctions, have caused a significant decline in the educational system, affecting both academic curricula and teaching techniques, particularly in the field of medical education in Iraq. The medical education and training system faced numerous challenges due to the lack of facilities and financial support, as well as the migration of physicians driven by violence and political unrest (38).

In Serbia, before the sanctions, public services, including education and healthcare, were mainly provided by the government. However, after the sanctions and subsequent financial problems of the government, the private sector gradually entered these fields, creating social inequalities. Specialists in medical sciences were prohibited from international travel, their access to scientific information was limited, and their international research budgets were cut off (39). In Sudan, sanctions significantly impacted Sudanese academics, leading foreign organizations to refrain from collaborating on research or publishing articles with them (11). Dezhina (2015) reports that the direct consequences of economic sanctions in Russia were quickly reflected in higher costs and decreased competitiveness of research activities. The lack of imported foreign equipment and reagents, combined with the rising costs of these materials due to the depreciation of the ruble, negatively affected research in universities and research centers (40). Therefore, it is undeniable that sanctions can have a negative impact on education and research, particularly in medical sciences.

In Iran, economic sanctions have negatively affected the higher education system. Approximately 5% of public universities are directly supervised by the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology, nearly 66% are semi-public universities, and 28% are private and non-governmental universities. The budget allocated to public universities comes from government appropriations, while private universities are financed through private investment and high tuition fees. Therefore, the administration of universities is entirely dependent on the economic state of the country (9).

The integration of medical education and healthcare has made the medical education system responsible for the treatment of the community, and the adverse effects of sanctions particularly influence this aspect. Sanctions can impose additional stress and hardships on patients due to drug shortages and high costs (41). They also impact research in universities, particularly those related to medical sciences. During periods of heightened sanctions, Iranian scientists were increasingly deprived of opportunities to publish their scientific findings, participate in scientific meetings, or access essential medical and laboratory equipment and information (42). As Mehrabi states, in international arenas, particularly scientific conferences, this situation, coupled with difficulties in obtaining visas for the countries hosting these events, has caused the isolation and marginalization of Iranian academics. The effects of these sanctions have been so severe that some students, who had studied abroad relying solely on financial support from their families, were forced to return to Iran after the unprecedented drop in the Iranian currency (9). This review was conducted to explore how medical education is affected by economic crises. Economic sanctions are among the most severe and detrimental economic crises a country can face.

4. Discussion

Economic downturns have a significant impact on education, particularly medical education. Similarly, economic sanctions pose substantial challenges to the education system, with higher education often bearing the brunt. As Mehrabi points out, a nation's economy is intrinsically linked to its citizens' well-being in multiple ways. Higher education is a sector highly susceptible to fluctuations in a nation's economy (9). A review of evidence during an economic crisis in India showed that the deterioration of the adult labor market discouraged parents from supporting their children's education (2). In Nigeria, an economic crisis led to a decrease in government financial support for the education sector, negatively impacting the implementation of educational curricula (43). Nambissan argues that during the economic recession in India, the agendas of private schools became driven by markets and profits, and the regulatory role of the government in education was reduced, resulting in serious consequences (44). As mentioned earlier, economic sanctions in Zimbabwe led to poor working conditions for teachers and the closure of 94% of primary schools until January 2009 (22). The negative consequences of economic sanctions on Iraq went beyond their observed impact on public health; the major impact of the 1990 - 2003 sanctions was associated with reduced primary school enrollment in Iraq (37).

Medical education is no exception and is similarly negatively affected by societal economic crises. Following the 1999 economic crisis, academic medical leaders in the U.S. announced that American university hospitals faced an unprecedented financial crisis, which might force these hospitals to cut back on their traditional teaching programs and eliminate a wide range of community health projects and care programs for underserved populations (45). Similarly, the Greek economic crisis severely impacted the country’s medical education system. A notable consequence was undergraduate students’ drastically reduced access to essential textbooks. Significant reductions in government aid to research funding also affected medical schools and jeopardized high-quality research (3). For some individuals, attending university may result in indifference, exhaustion, and inefficiency, rather than positive experiences (46).

The conflicts and economic sanctions in Iraq caused a decline in the quality of both academic curricula and teaching techniques within the educational system. Furthermore, medical education in Iraq faced numerous challenges due to these conditions. Educational researchers in Iraq believe that active learning should be strengthened through modern educational methods such as problem-based learning (PBL) (38). Crises, whether human-induced or natural, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitate a shift from traditional classroom instruction to technology-based learning in medical education (47). Khoshnoodifar et al. advocate for the role of e-learning in improving the quality of higher education (48), while Khoshgoftar and Karimi Rouzbahani emphasize the potential of artificial intelligence in this field (49).

The medical education system in Iran has its own unique characteristics. In 1985, the ministry of health, treatment, and medical education was established independently of the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology. This resulted in significant growth in the number and range of disciplines in basic medical sciences, health, rehabilitation, nursing and midwifery, and allied medical sciences (50). One of the key features of the medical education system in Iran is the integration of clinical and academic fields. In other words, in addition to offering academic courses at universities and university hospitals, the medical education system in Iran is responsible for providing healthcare services throughout the country (51). Promoting medical professionalism among students is a top priority for Iranian medical schools (52).

Regarding the characteristics of medical education in Iran, Azizi insists that the health system must be accountable not only for the quality of services provided by health service providers but also for the knowledge, attitudes, skills, and abilities of the providers who graduate. The separation of clinical and academic fields would reduce this accountability on two levels (51). The integration of theoretical and clinical fields makes the Ministry of Health, Treatment, and Medical Education more vulnerable than other educational institutions during economic crises, particularly in terms of education and research at the university level, as well as in providing health and therapeutic services. Majidi et al. contend that universities are prime environments for fostering innovation and delivering services (53). Gheshlaghi Azar et al. assert that critical thinking is a key educational outcome for health professionals (54).

Economic crises often lead companies to reduce their investment in innovation (1), which in turn leads to scientific and cultural dependence. Momeni suggests that this effect can also impact the next generation to some extent. Estimates indicate that economic sanctions have reduced Iran's national income by approximately 18% of its GDP. This loss is primarily attributed to a 45% decline in current workers' income and a 55% decrease in income for the subsequent generation. According to Arjo and Cuesta, in Iraq, the negative and lasting effects of the sanctions led to the economic and social marginalization of many people, causing disruption in their education. As a result, they will be lagging behind in this regard for a long time (37).

The effects of economic sanctions on primary and high school education, university education, and especially medical education are inevitable. However, what Momeni points out is that these effects will not be compensated even after the sanctions are lifted. By depriving students of the education they need, these sanctions will have long-term consequences for the well-being of these students (8). Therefore, a collective effort to exclude educational systems from these sanctions should be urgently prioritized by all international educational institutions, especially those related to medical education.

4.1. Conclusions

Education plays a crucial role in the development of any society, which is why the United Nations considers education a fundamental human right and emphasizes that higher education should be accessible to everyone. Economic sanctions, as foreign policy tools, can have destructive effects on human rights in target societies. They limit both access to and the quality of higher education in the target country by negatively affecting its economy. The impact of sanctions on education and health in countries such as Sudan, Haiti, Zimbabwe, and Iraq has already been demonstrated. While damaged educational systems are only one of the numerous destructive effects of sanctions, there is an urgent need to focus specifically on the educational consequences above all other aspects. In Iran, considering the responsibility of the medical education system towards the health and well-being of society, any disruption or failure in this system can have irreparable consequences.

4.2. Highlights

Given the impact of economic sanctions on medical education, the need to investigate resilience strategies in such conditions is evident.

Studies have shown an overall impact of economic sanctions on medical education, necessitating quantitative and qualitative research into the nature of this impact.

The provision of practical resilience strategies in the context of economic sanctions, considering the type of damage, is another point that should be examined by researchers.

4.3. Lay Summary

Sanctions are penalties imposed by certain governments, powerful organizations, or global institutions against specific countries. One type of sanction is an economic sanction. Economic sanctions affect various economic aspects of the target country, causing numerous economic problems for its people. The negative effects of these sanctions have been studied from various perspectives, but there is limited information available regarding their impact on medical education. In this research, we found that while economic sanctions can accelerate innovation and self-sufficiency in some areas, they generally have a negative impact on both theoretical and clinical aspects of medical education.