1. Background

Malaria, a parasitic disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite, transmitted through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes (1), remains a significant global health challenge, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, as exemplified in Africa (2). While malaria primarily affects the blood and can lead to severe health complications (3), recent studies suggest its potential effects on the reproductive system and health (4, 5).

Chronic malaria infections have been linked to sexual dysfunction in males (4), possibly due to disruptions in the endocrine system leading to hormonal imbalances (6, 7). Moreover, malaria has been associated with reduced sperm quality, including decreased sperm count, impaired motility, and abnormal morphology (4, 7). Severe malaria infections may also lead to testicular damage due to inflammation and oxidative stress (8). Therefore, there is a need to explore the testicular protective potential of herbs used in the traditional treatment of malaria. One such medicinal plant is Azadirachta indica.

Azadirachta indica, commonly known as neem, has garnered attention for its potential effects on reproductive health (9). Neem has been traditionally used as a natural contraceptive (10) and has shown antimicrobial properties against sexually transmitted infections (9, 11). Research has explored neem's impact on male and female fertility (5, 12), including its potential to disrupt embryo implantation in females (13).

While much research has focused on malaria's general health impact, recent evidence suggests its effects on male reproductive health. This study investigates the reproductive effects of neem leaf extract on Plasmodium berghei-infected mice, contributing to our understanding of both malaria treatment and its potential reproductive consequences.

2. Objectives

By examining plant-based treatments and their implications for reproductive health, this study addresses critical health challenges, particularly in developing countries, and aims to improve overall well-being.

3. Methods

3.1. Preparation of Plant Extracts

The plant was harvested in Abraka, Delta State, Nigeria. The plant's identity was confirmed using the LeafSnap App at the collection site and authenticated in the Department of Botany, Delta State University (DELSU), Abraka, Nigeria. After plucking, the leaves were rinsed in running tap water, air-dried, and finely powdered. The powdered leaves underwent maceration extraction using absolute ethanol with intermittent shaking for 72 hours. The resulting mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated using a freeze dryer to obtain the ethanol extract of A. indica leaves, which was stored frozen until required for use.

3.2. Oral Acute Toxicity

This was performed in vivo by administering a single oral dose of 5,000 mg/kg of ethanol leaf extract of Azadirachta indica (EEAi) to mice, following the procedure outlined by Ugbogu et al. (14).

3.3. Assessment of In Vivo Antiplasmodial Activity (Curative Study)

Thirty male mice were used, and P. berghei-infected donor mice were sourced from the Nigerian Institute for Medical Research, Lagos, Nigeria. Animal handling complied with the ARRIVE guidelines, and ethical approval was provided by the Research and Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, DELSU, Abraka.

3.4. Experimental Design

The curative test, conducted as described by Christian et al. (15), involved the administration of various doses (100, 200, 400 mg/kg) of the ethanol extract of A. indica to different groups of mice, along with controls, and monitoring of treatment effects.

3.5. Determination of Plasmodial Load in Blood Samples

Blood samples were collected and stained for parasite counts using established methods (16, 17), followed by examination under a microscope.

3.6. Hormonal Assays

Serum levels of testosterone, follicular stimulating hormone, Anti-Müllerian hormone, and luteinizing hormone were measured using ELISA kits and methods already described (18).

3.7. Epididymal Spermatozoa Collection and Examination

Spermatozoa were collected from the epididymis and analyzed following established procedures (19, 20). Superoxide dismutase activity, catalase activity, glutathione level, lipid peroxidation, and nitric oxide concentration in testicular homogenate were measured using standard methods (21-24).

3.8. Immunohistochemical Staining

About 5 to 10 μm sections of tissue samples were cut onto multiwell slides with a cryostat and air-dried overnight. The sections were fixed in acetone for 10 min and air-dried for 30 min at room temperature. They were then stored at -20°C until use. Sections were incubated with a 1:20 dilution of normal swine serum in TBS in a humidified chamber for 20 min to reduce nonspecific binding and then stained using the indirect immunoperoxidase technique (25). Negative controls included the omission of the primary antibody and the use of isotype-specific monoclonal antibodies recognizing antigens of the murine malaria parasite, P. berghei. Positive controls were antibodies recognizing constitutive endothelial antigens known to be expressed in the organ examined.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Results were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) for n = 5 mice/group in murine experiments, and in triplicates for phytochemical profiling. Data were subjected to ANOVA and Tukey post hoc analyses using GraphPad Prism (V 7). P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The results obtained from the investigation into the impact of A. indica’s antimalarial efficacy on testicular functions are presented below in the following order:

4.1. Toxicity Effects

Acute Toxicity of EEAi has been shown in Table 1.

| Observations | Control | Azadirachta indica | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 14 Days | ||

| Consciousness | N | N | N | N | N |

| Grooming | N | N | N | N | N |

| Touch response | N | N | N | N | N |

| Sleeping duration | N | N | N | N | N |

| Movement | N | N | N | N | N |

| Gripping strength | N | N | N | N | N |

| Righting reflex | N | N | N | N | N |

| Food consumption | N | N | N | N | N |

| Water intake | N | N | N | N | N |

| Tremors | A | A | A | A | A |

| Diarrhea | A | A | A | A | A |

| Hyperactivity | A | A | A | A | A |

| Corneal reflex | N | N | N | N | N |

| Salivation | N | N | N | N | N |

| Skin colour | N | N | N | N | N |

| Lethargy | A | A | A | A | A |

| Convulsion | A | A | A | A | A |

| Sound response | N | N | N | N | N |

| Pinna reflex | N | N | N | N | N |

| Faecal appearance | N | N | P | P | N |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: N, normal; A, absent; P, pasty.

No fatalities related to the treatment were observed over the 3-hour monitoring period and the subsequent 14-day test period. Observations indicated no noticeable changes in general behavior, with no toxicity signs detected. Consequently, the LD50 of EEAi is established to be greater than 5,000 mg/kg body weight.

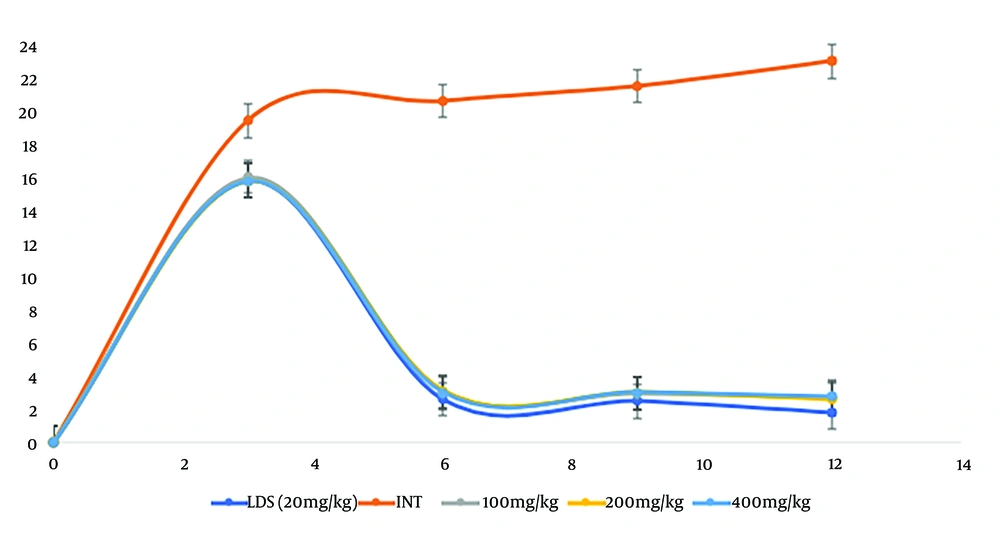

Following the confirmation of parasitaemia post-inoculation, a 4-day oral treatment with varying doses of EEAi and the standard drug (Lonart® DS) was initiated. Blood parasite levels were estimated at 0-, 3-, and 6-days post-treatment (dpt). These values were used to calculate changes in parasitaemia across the different dpt, as depicted in Figure 1.

Indicates that all the doses of ethanol leaf extract of Azadirachta indica (EEAi) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced blood parasitaemia at the end of the 4-day treatment period with EEAi, and this compared well with the standard drug. The reduced levels were sustained throughout the periods of the study (6th dpt), indicating that EEAi is parasitocidal.

4.2. Effects on Hormonal Levels

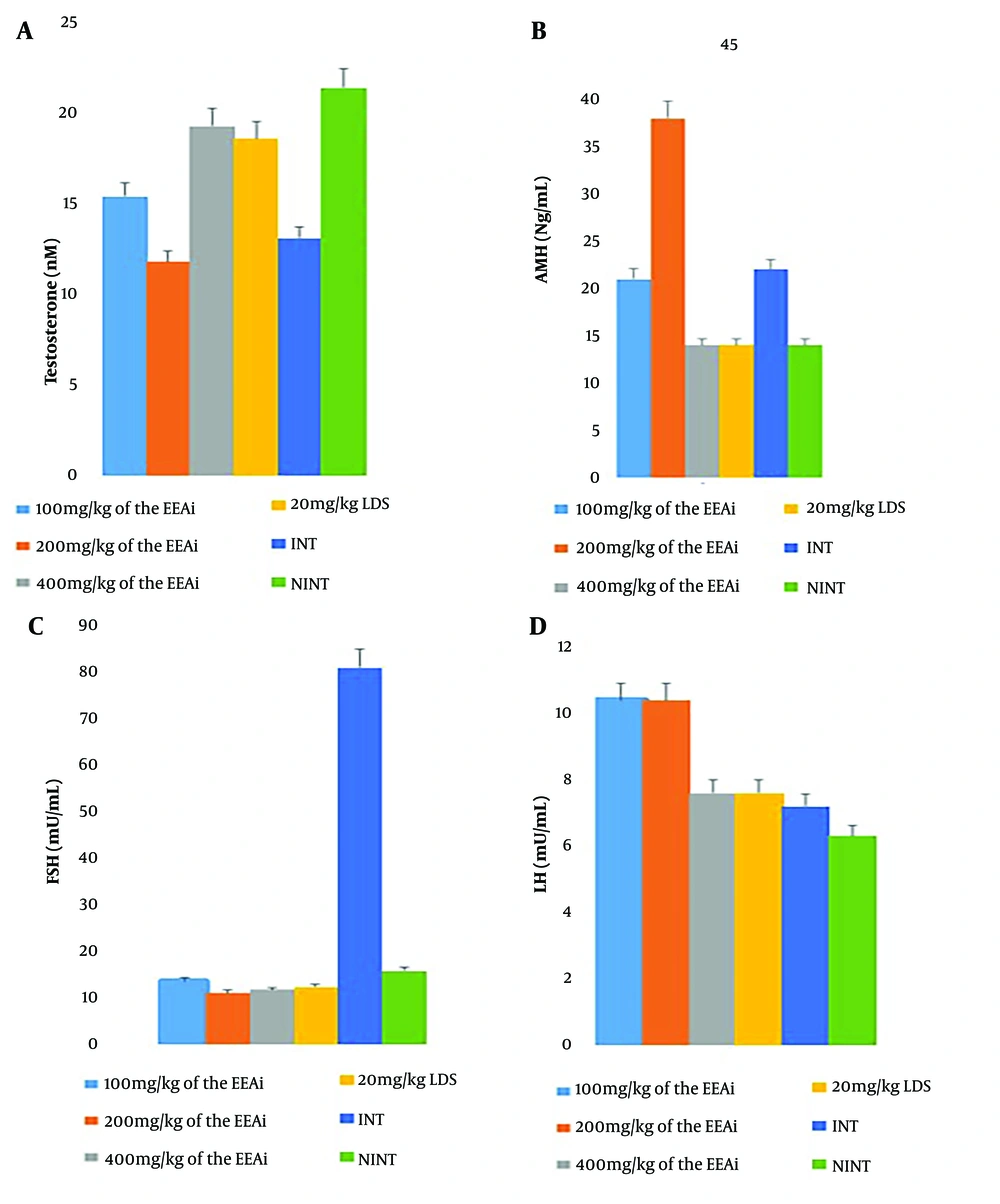

Changes in the hormonal profile of malaria-infected mice treated with EEAi has been shown in Table 2.

| Hormones | EEAi (mg/kg) | LDS 20 | INT | NINT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 400 | ||||

| Testosteronen (M/L) | 15.4 ± 1.3 A | 11.8 ± 0.8 A | 19.3 ± 4.5 A | 18.6 ± 3.4 A | 13.1 ± 1.2 B | 21.4 ± 1.2 A |

| AMH (ng/mL) | 21 ± 0.8 A | 38 ± 3.9 B | 14 ± 3.5 A | 14 ± 6.1 A | 22 ± 0.3 B | 14 ± 1.8 A |

| FSH (mU/mL) | 13.5 ± 2.7 A | 11.0 ± 0.7 A | 11.7 ± 1.1 A | 12.4 ± 1.0 A | 81.0 ± 6.8 B | 15.8 ± 1.9 A |

| LH (mU/M) | 10.4 ± 0.4 A | 10.4 ± 0.2 A | 7.6 ± 1.6 A | 7.6 ± 1.6 A | 7.2 ± 4.2 A | 6.3 ± 1.6 A |

Abbreviations: INT, infected not treated; NINT, not infected not treated; AMH, anti mullerian hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; LDS, Lonart®DS.

a Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 5 mice/group. Different superscript capital letters show significant different.

Malaria infection in experimental mice led to a decrease in PCV, Hb, RBC, and platelet levels, along with an increase in WBC count. However, treatment of the infection with the EEAi and the standard drug (Lonart® DS) rejuvenated these hematological parameters. An inverse relationship was observed between Hb and WBC levels across all treated groups.

Based on MCHC values, malaria infection in mice induced hyperchromic anemia, but treatment with graded doses of EEAi and Lonart® DS effectively restored this anemic condition, with the exception of the lowest dose (100 mg/kg) of EEAi (Figure 2).

4.3. Effects on Sperm Characteristics

Changes in Semen Parameters of malaria-infected mice Treated with EEAi has been shown in Table 3.

| Semen Parameters | EEAi (mg/kg) | LDS 20 | INT | NINT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 400 | ||||

| Viscosity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | None | Yes |

| Morphology (%) | 20 ± 0.13 A | 12.5 ± 10.6 A | 7.5 ± 3.5 A | 12.0 ± 2.5 A | 80 ± 10 A | 5 ± 0 A |

| Head (abnormal) | 13.5 ± 9.2 A | 7.5 ± 3.5 A | 10 ± 7.1 A | 17.5 ± 2.9 A | 81.7 ± 2.9 A | 15 ± 5 A |

| Tail (abnormal) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Volume (mL) | 1.5 ± 0 A | 1.5 ± 0 A | 1.5 ± 0 A | 1.5 ± 0 A | 0.3 ± 0.1 B | 1.5 ± 0 A |

| Sperm count | 24.5 ± 0.7 A | 20 ± 0 A | 20.5 ± 0.7 A | 24.3 ± 1.2 A | 4 ± 1 A | 26 ± 2.6 C |

| Mortility (%) | 55.5 ± 0.7 A | 67.5 ± 3.5 A | 72.5 ± 3.5 A | 66.7 ± 15.3 A | 7.3 ± 2.5 B | 80.3 ± 10.0 C |

| Viability (%) | 50.0 ± 0 A | 50.5 ± 0.7 A | 52.0 ± 1.4 A | 56.7 ± 10.7 A | 4.7 ± 2.5 B | 62.3 ± 2.5 B |

| pH of semen | 7.8 ± 0 A | 7.8 ± 0 A | 7.7 ± 0.1A | 7.5 ± 0 A | 6.0 ± 0 B | 7.5 ± 0 A |

Abbreviations: INT, Infected not treated; NINT, not infected not treated; LDS, Lonart®DS.

a Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 5 mice/group. Different superscript capital letters show significant different.

4.4. Effects on Oxidative Markers

Changes in testicular oxidative markers of malaria-infected mice treated with EEAi has been shown in Table 4.

| Dose (mg/kg) | EEAi | LDS 20 | INT | NINT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 400 | ||||

| MDA (µM) | 12.6 ± 2.0 A | 14.2 ± 3.9 A | 28.1 ± 2.8 A | 15.8 ± 4.6 A | 57.0 ± 2.5 B | 16.8 ± 3.8 A |

| GSH (µM) | 8.3 ± 4.1 A | 6.7 ± 0.8 A | 11.4 ± 1.4 A | 12.1 ± 2.1 A | 0.50 ± 0.6 B | 12.5 ± 2.3 A |

| GPx (mU/mL) | 5 ± 0.1 A | 4.5 ± 0.8 A | 5.8 ± 0.2 A | 4.7 ± 1.7 A | 0.07 ± 0.02 B | 5.4 ± 0.7 A |

| SOD (U/mL) | 0.5 ± 0.03 A | 0.6 ± 0.1 A | 0.6 ± 0.06 A | 0.67 ± 0.2 A | 0.06 ± 0.02 B | 0.68 ± 0.2 A |

| CAT (U/mL) | 12.4 ± 0.3 A | 11.8 ± 1.8 A | 10.3 ± 0.4 A | 11.4 ± 1.2 A | 1.0 ± 0.3 B | 11.1 ± 0.9 A |

| NO (µmol/L) | 11.8 ± 0.8 A | 22.3 ± 11.2 A | 13.3 ± 1.6 A | 26.0 ± 3.9 A | 1.6 ± 0.4 B | 21.4 ± 9.1 A |

| TAC (µM) | 0.06 ± 0.004 A | 0.05 ± 0.004 A | 0.08 ± 0.003 A | 0.06 ± 0.01 A | 0.008 ± 0.002 B | 0.07 ± 0.01 A |

Abbreviations: MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; Gaps, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; NO, nitric oxide; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; INT, infected not treated; NINT, not infected not treated; EEAi, ethanol leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; LDS, Lonart®DS.

a Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 5mice/group. Different superscript capital letters show significant different.

4.5. Effects on Proliferating Cells Nuclear Antigen Expression

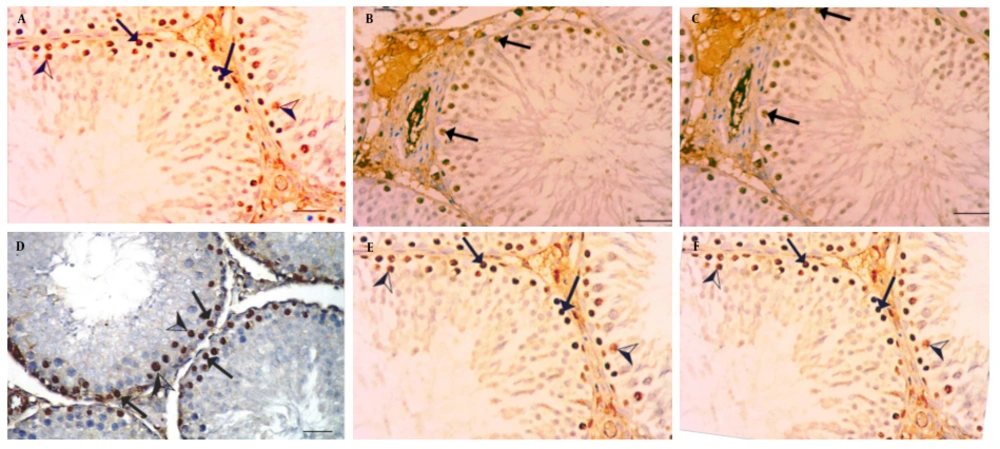

The testicular expression of PCNA, assessed through immunohistochemical staining, is illustrated in Figure 3A - F.

A, Positive control; B, (400 mg/kg A. indica + PB); C, (200 mg/kg A. Indica + PB); D, PB: Infected negative control; E, (standard control + PB + Lonart®DS); F, (100 mg/kg A.Indica + PB) showing view positive nuclear immune reaction in spermatogonia (arrows), while (D) PB infected negative control, illustrates strong positive nuclear immuno reaction in spermatogonia (arrows) for proliferating cells nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunoreaction (400 scale bar, 20 µm).

5. Discussion

This study investigated the toxicity and antimalarial potential of A. indica on testicular functions in experimental mice. The plant contains phytochemicals with medicinal properties (26) and demonstrated no toxicity (Table 1). The EEAi showed significant parasite suppression and parasiticidal effects comparable to standard drug treatment, supporting its traditional use in treating malaria and fever (26). The study found a notable antimalarial effect of A. indica, evidenced by the percentage of parasite suppression in the blood (Figure 1). All three doses of the ethanol extract showed efficacy similar to Lonart®DS, the standard drug. The reduction in parasitemia on Days 6, 9, and 12 suggests the antimalarial potential of A. indica, consistent with previous studies highlighting the plant’s antiparasitic effects (27, 28).

Maintaining proper sperm characteristics is essential for male fertility. Data on parameters related to testicular health, including hormone levels (testosterone, AMH, FSH, LH), sperm characteristics (viscosity, morphology, volume, count, motility, viability, pH), and antioxidant profile, indicate the restorative effects of EEAi against malaria-induced testicular dysfunction and damage. Ethanol leaf extract of A. indica treatment positively influenced testosterone levels, a key hormone for male reproductive health (Table 2). Additionally, A. indica showed potential in enhancing sperm count, motility, viability, and morphology (Table 3), highlighting its beneficial effects on male reproductive health.

Furthermore, our evaluation of testicular function revealed notable improvements in testosterone levels, AMH, FSH, and LH (Figure 2), as well as in semen parameters such as sperm count, motility, viability, and morphology. These findings are consistent with the study by El-Beltagy et al. (29), which demonstrated the ameliorative effects of neem leaf extract on the testes of diabetic male rats, similarly observed in this study using malaria-infected rats.

Azadirachta indica exhibited antioxidant activity by modulating oxidative markers such as MDA, GSH, GPx, SOD, CAT, NO, and TAC (Table 4). These findings indicate that A. indica possesses antioxidant properties, which may play a protective role against oxidative damage in testicular tissue induced by malaria infection. This aligns with Hla et al.'s study (30), which emphasized the antioxidant potential of A. indica, and similar findings have been reported for P. amarus (31). Thus, A. indica exhibits antioxidant activity, helping to reduce oxidative stress in Plasmodium berghei-infected cells, thereby impairing parasite survival and proliferation.

The photomicrographs of PCNA immunostained testicular sections from mice subjected to different treatments are displayed in this study (Figure 3). The staining highlights PCNA, a marker of cellular proliferation, showcasing the nuclear immune reaction in spermatogonia for each treatment group. The A. indica treatments in various doses (Figure 3B, C, F) and the standard drug treatment (Lonart®DS) show varying degrees of nuclear immune reactions in spermatogonia, providing insights into the effects of these treatments on cellular proliferation within the testes. The results indicate a downregulation of PCNA gene expression in the treated and positive control groups when compared with the negative group, suggesting that A. indica leaf extract may exhibit antimalarial properties by modulating PCNA gene expression. This observation aligns with findings by Onuegbu et al. (32), who reported significant changes in the photomicrographs of organs from diabetic rats treated with neem leaf extract.

Histological evaluations of the testes further corroborated our findings, showing minimal injury in the testicular tissue of mice treated with A. indica, particularly at higher doses (Table 5). This suggests a potential protective role of A. indica in mitigating testicular damage caused by P. berghei infection.

| Scoring | NINT | LDS | INT | EEAi (mg/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 400 | ||||

| Seminiferous tubules | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Germinal epithelium | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Superficial and deep cells | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 3/12 | 4/12 | 9/12 | 4/12 | 3/12 | 3/12 |

Abbreviations: INT, infected not treated; NINT, not infected not treated; EEAi, ethanol leaf extract of Azadirachta indica; LDS, Lonart®DS.

a 1 = Necrosis in superficial cells, 2 = Necrosis in superficial and deep cells with structural damage, 3 = Distal necrosis in germ cells, 4 = Disappearance of tubular structures.

A few limitations were observed during the study, including the lack of strict control over environmental and dietary factors that could potentially influence reproductive outcomes. Overall, the study demonstrates the positive influence of A. indica on testicular functions in P. berghei-infected mice.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the antimalarial efficacy of A. indica, demonstrated by its significant suppression of P. berghei parasitemia. Furthermore, A. indica shows potential in preserving testicular function, reducing oxidative stress, and mitigating histological damage in testicular tissue. These beneficial effects are likely due to the antioxidant properties of A. indica, highlighting the need for further investigation to better understand the underlying mechanisms.