1. Background

Graduates of medical universities must acquire competencies beyond theoretical knowledge, so the curriculum is based on the competency-based approach, which in turn necessitates changes in student assessment methods from an overemphasis on knowledge to assessment in a real environment (1). Assessment is the study of the achievement of the desired goals in the learning activities of learners and is a tool to improve the quality of educational programs, motivate students to learn, and guide them toward educational goals (1, 2). Therefore, assessment seeks to strengthen effective educational programs and methods and weaken or eliminate ineffective or undesirable programs (3).

Clinical assessment of medical students in clinical environments is of great importance to ensure their proper progress based on the goals of the program and the extent to which these goals are achieved (4, 5). Assessment in the clinical environment is crucial and requires evidence that the student has acquired the necessary competence to function properly in the real environment (6). Medical assessment methods, especially in clinical education, often lack the necessary efficiency in assessing practical skills due to insufficient educational goals (7). Multiple and combined methods are currently needed for the assessment of clinical capability as a complex structure. These assessment methods, such as portfolio, Logbook, mini-clinical evaluation exercise (Mini-CEX), objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), and direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS), may involve patients in hospitals and other healthcare facilities, communities, simulation and learning laboratories, and virtual environments. Many of the student assessment methods in medical universities are conducted using traditional methods such as multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and general assessment by professors (8-11).

Based on studies, the OSCE method can assess students' clinical skills more effectively than common clinical assessment methods, leading to greater student satisfaction (12). Additionally, the use of DOPS and Mini-CEX assessment methods, compared to traditional methods, has improved the clinical skills of students (13). According to research findings, the usual assessment of students is often limited to subjective information, with little attention given to accurately assessing their clinical skills (14). Moreover, the assessment methods in most clinical courses do not align with educational goals and lack efficiency in measuring clinical skills and student performance. Although clinical skills and practical work are central to medical education, the success of medical students in these exams largely depends on their mental reservations (15, 16). While skill and practical work play the main role in medical education, mental information is of secondary importance (17).

Furthermore, the implementation of traditional assessment methods has led to student dissatisfaction. A study showed that 62% of male students and 82% of female students believed that not all skills could be evaluated through conventional assessment, and this dissatisfaction can be an inhibiting factor in learning (18). Given the ever-increasing changes in clinical education approaches, the need to use new assessment methods that are appropriate to these changes is becoming more apparent. Research conducted in the nursing schools of South American states found that 45% of the schools had not revised their clinical assessment methods for 5 years, 35% for 6 - 10 years, 17% for 11 - 15 years, and 3% for more than 15 years (19). Additionally, research in nursing schools in Tehran determined that 62% of the students believed that the clinical assessment conditions and cases were not consistent and satisfactory for all students (20).

At the same time, there is no single method universally used among educational groups, so some tests may be more frequently used while others are less commonly applied. Since each test has a specific score for clinical performance assessment, the proper use of these tests can significantly affect the quality of assessment. Therefore, it seems necessary to investigate the extent and factors affecting the use of these tests.

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate the extent of use of different clinical assessment methods for medical students at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

In this observational study, educational records of the exam methods used to evaluate the clinical performance of medical students by 19 educational departments of the medical school at KUMS from 2014 to 2019 were analyzed. For this purpose, we gathered data from two sources: Educational supervisors and faculty members (attending) of educational departments simultaneously. The inclusion criteria for faculty members were having at least 1 year of experience participating in the exams and willingness to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for educational supervisors (usually nurses with experience in the field of educational management) were access to records of the exams in the given department and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criterion for both faculty members and educational supervisors was incomplete checklists. Informed consent was provided by all participants. Finally, 19 educational supervisors and 195 faculty members participated in this study.

3.2. Measures

We used two separate checklists for educational supervisors and faculty members. The checklist for faculty members included two parts. The first part assessed demographic information of the faculty member, such as their work experience. The second part dealt with questions about the methods used for the assessment of medical students in two stages: Extern (stager stage) and intern. The questions were answered dichotomously with "Yes" or "No", and "Yes" answers were further categorized into three options using a Likert scale: "Occasionally", "Usually", and "Always".

The methods used included OSCE, objective structured practical examination (OSPE), key feature (KF), objective structured lab examination (OSLE), patient management problem (PMP), Mini-CEX, script concordance (SC), DOPS, case-based discussion (CBD), multi-source feedback (MSF), and global rating form (GRF). These methods have been considered in the general practice curriculum.

The checklist for educational supervisors included questions about the methods used for the clinical assessment of medical students in the two stages of extern and intern over a five-year period. The checklist was scored similarly to the checklist used for faculty members. Checklists were distributed as links via email or through training supervisors.

This checklist was initially compiled by two members of the research team. The basis for designing this checklist was a review of past studies regarding the types of tests used in clinical assessment. In the second step, this tool was reviewed by the research team, and their corrective comments were applied. In the third stage, the finalized checklist was approved by the research team members and three medical education experts in terms of face and content validity.

The assessments included written short answer examinations, which evaluate knowledge recall and application but are not clinical tests in the strict sense. Based on Miller’s Pyramid of Clinical Competence, MCQs and short answer questions (SAQs) primarily assess the ‘Knows’ and ‘Knows How’ levels, whereas OSCE and Mini-CEX evaluate higher levels of competence (‘Shows How’ and ‘Does’).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe demographic information and the frequency of exam methods used over five years and in the two stages of extern and intern. A series of cross-tabulations (frequency and percent) tests were performed to calculate the association between demographic characteristics and exam methods.

4. Results

The information on methods used for the clinical assessment of medical students at KUMS over a five-year period (2014 to 2019) was gathered from 19 educational supervisors of educational departments and 195 faculty members. Table 1 shows some demographic characteristics of faculty members who participated in this study. Of the participants, 74.4% were males. The anesthesiology department had the highest frequency of participants, while urology and social medicine had the lowest (9.7% and 1.5%, respectively). The category of 6 - 10 years was the highest frequency of work experience among the participants (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 50 (25.6) |

| Male | 145 (74.4) |

| Departments | |

| Anesthesiology | 19 (9.7) |

| Dermatology | 7 (3.6) |

| Diagnostic radiology | 0 (0) |

| Emergency medicine | 11 (5.6) |

| Internal medicine | 17 (8.7) |

| Neurology | 13 (6.7) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 8 (4.1) |

| Ophthalmology | 13 (6.7) |

| Pathology | 9 (4.6) |

| Pediatrics | 10 (5.1) |

| Psychiatry | 5 (2.6) |

| Surgery | 18 (9.2) |

| Urology | 3 (1.5) |

| Infectious disease | 9 (4.6) |

| Cardiology | 9 (4.6) |

| Orthopedic | 9 (4.6) |

| Neurosurgery | 12 (6.2) |

| Social medicine | 3 (1.5) |

| ENT | 8 (4.1) |

| Oncology | 8 (4.1) |

| Work history | |

| 1 - 5 | 45 (23.1) |

| 6 - 10 | 47 (24.1) |

| 11 - 15 | 35 (17.9) |

| 16 - 20 | 24 (12.3) |

| 21 - 25 | 17 (8.7) |

| 26 - 30 | 24 (12.3) |

| 31 - 35 | 3 (1.5) |

| Academic rank | |

| Educational co-worker | 13 (6.7) |

| Assistant professor | 114 (58.5) |

| Associated professor | 49 (925.5) |

| Professor | 19 (9.7) |

In Table 2, the methods used for the clinical assessment of medical students in the intern stage are included. As seen in Table 2, MCQs, short answers, OSCE, and Mini-CEX had the highest frequency of being used "always" (26.7%, 12.3%, 11.3%, and 11.3%, respectively), while portfolio (97.9%), CBD and GRF (97.4%), 360-degree feedback (93.8%), and DOPS (93.3%) were the methods with the highest frequency of "not used" (Table 2).

| Methods | Never | Sometimes | Most of the Times | Always | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi choice | 127 (65.1) | 4 (2.1) | 12 (6.2) | 52 (26.7) | 195 (100.0) |

| Classify | 180 (92.3) | 7 (3.6) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| Widen response | 174 (89.2) | 6 (3.1) | 6 (3.1) | 9 (4.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| Short answer | 158 (81.0) | 6 (3.1) | 7 (3.6) | 24 (12.3) | 195 (100.0) |

| Descriptive | 172 (88.2) | 7 (3.6) | 6 (3.1) | 10 (5.1) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSCE | 153 (78.5) | 7 (3.6) | 13 (6.7) | 22 (11.3) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSPE | 189 (96.9) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSLE | 190 (97.4) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| PMP | 177 (90.8) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| SC&KF | 193 (99.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| Long case | 185 (94.9) | 6 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.1) | 195 (100.0) |

| Mini-CEX | 161 (82.6) | 3 (1.5) | 9 (4.6) | 22 (11.3) | 195 (100.0) |

| DOPS | 182 (93.3) | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.1) | 5 (2.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| CBD | 191 (97.9) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| Logbook | 181 (92.8) | 4 (2.1) | 2 (1.0) | 8 (4.1) | 195 (100.0) |

| Portfolio | 191 (97.9) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| 360 D (MSF) | 183 (93.8) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| GRF | 190 (97.4) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 195 (100.0) |

Abbreviations: OSCE, objective structured clinical examination; OSPE, objective structured practical examination; OSLE, objective structured lab examination; PMP, patient management problem; SC, script concordance; KF, key feature; Mini-CEX, mini-clinical evaluation exercise; DOPS, direct observation of procedural skill; CBD, case-based discussion; 360 D, 360-degree; MSF, multi-source feedback; GRF, global rating form.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

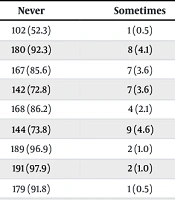

The results of methods used for clinical assessment in the stager stage are listed in Table 3. In the stager stage, MCQs (37.9%), short answers (20%), Mini-CEX (18.5%), and OSCE (16.9%) were the methods with the highest frequency of being used "always". As seen in Table 3, SC&KF, and GRF (98.5%), OSLE (97.9%), portfolio (97.7%), and CBD (96.6%) were the methods with the highest frequency of "not used" (Table 3).

| Methods | Never | Sometimes | Most of the Times | Always | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi choice | 102 (52.3) | 1 (0.5) | 18 (9.2) | 74 (37.9) | 195 (100.0) |

| Matching | 180 (92.3) | 8 (4.1) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| Widen response | 167 (85.6) | 7 (3.6) | 6 (3.1) | 15 (7.7) | 195 (100.0) |

| Short answer | 142 (72.8) | 7 (3.6) | 7 (3.6) | 39 (20.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| Descriptive | 168 (86.2) | 4 (2.1) | 6 (3.1) | 17 (8.7) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSCI | 144 (73.8) | 9 (4.6) | 9 (4.6) | 33 (16.9) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSPE | 189 (96.9) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| OSLE | 191 (97.9) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| PMP | 179 (91.8) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 12 (6.2) | 195 (100.0) |

| SC&KF | 192 (98.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| Long case | 188 (96.4) | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| Mini-CEX | 146 (74.9) | 5 (2.6) | 8 (4.1) | 36 (18.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| DOPS | 179 (91.8) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.6) | 10 (5.1) | 195 (100.0) |

| CBD | 189 (96.9) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

| Logbook | 183 (93.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.6) | 7 (3.6) | 195 (100.0) |

| Portfolio | 190 (97.4) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 195 (100.0) |

| 360 D (MSF) | 185 (94.9) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (3.1) | 195 (100.0) |

| GRF | 192 (98.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 195 (100.0) |

Abbreviations: OSPE, objective structured practical examination; OSLE, objective structured lab examination; PMP, patient management problem; SC, script concordance; KF, key feature; Mini-CEX, mini-clinical evaluation exercise; DOPS, direct observation of procedural skill; CBD, case-based discussion; GRF, global rating form.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

In this study, we reviewed the methods used for the clinical assessment of medical students in the medical school of KUMS from 2014 to 2019. A total of 195 faculty members from 19 educational departments participated in this study. Our results showed that in both the intern and stager stages, more comprehensive assessment methods were not always used. The most widely used forms of clinical examination were MCQ, short answer, OSCE, and Mini-CEX. These findings are consistent with the results of studies conducted by Bahraini Toosi and Kouhpayezadeh et al. in MUMS and TUMS (11-21).

Although these methods may be useful in assessing some aspects of clinical performance, other important aspects of essential knowledge, such as technical, analytical, communication, counseling, evidence-based, system-based, and interdisciplinary care skills, cannot be assessed. Evaluations are essential steps in the educational process and have a powerful positive steering effect on learning, curriculum, and are purpose-driven (22). Assessment methods should be valid, reliable, and feasible, based on resources and time, and teachers should address what and why should be assessed. Different learning outcomes require different instruments (23-25).

If a large amount of knowledge is required to be tested, MCQs should be used due to their maximum objectivity, high reliability, and relative ease of execution (17). However, limitations of MCQs include the level of applied knowledge (taxonomy), compliance with structural principles, and post-test indicators (26).

The MCQs, essays, and oral examinations can be used to test factual recall and applied knowledge, but more sophisticated methods are needed to assess clinical performance, such as directly observed long and short cases and OSCEs with the use of standardized patients (27). Short answer questions are an open-ended, semi-structured question format. A structured predetermined marking scheme improves objectivity, and the questions can incorporate clinical scenarios (28).

The Mini-CEX is used to assess six core competencies of residents: Medical interviewing skills, physical examination skills, humanistic qualities/professionalism, clinical judgment, counseling skills, and organization and efficiency (29). The OSCE has been widely adopted as a tool to assess students' or doctors' competencies in a range of subjects. It measures outcomes and allows for very specific feedback (13).

Clinical competence has a complex structure, and multiple and combined methods are needed for valid assessment. Choosing appropriate tools for assessment is very important, so clinical teachers should be fully familiar with clinical measurement methods before using the tests appropriately (30). To accept an assessment method, the features of validity, reliability, practicality, and the positive feedback that the method will create on the trainee are very important. In addition, each method has advantages and disadvantages and is able to measure one or at most several specific aspects of students' clinical competence. Therefore, the use of each method depends on the purpose of the assessment and the specific aspect of the students' performance and clinical competence that is to be evaluated. Considering that clinical ability has a very complex structure, it is suggested to evaluate it authentically using multiple and combined methods (31).

In international studies, the use of Mini-CEX together with OSCE has been explored to provide a more holistic assessment of clinical skills. For example, Martinsen et al. in Norway implemented a cluster-randomized trial and found that students who underwent structured Mini-CEX assessments during clerkships had modest improvements on subsequent OSCE and written exams, suggesting that Mini-CEX may enhance formative feedback and observation in clinical settings (32). In another European study, Rogausch et al. observed that Mini-CEX scores were not strongly predicted by prior OSCE performance but were influenced by contextual features such as the clinical environment and trainer characteristics, pointing to the importance of implementation factors (33). Similarly, in Portugal, the translation and adaptation of Mini-CEX showed acceptable reliability when correlated with OSCE performance in various clinical domains, supporting its validity across cultural and linguistic contexts (34).

In the context of Miller’s Pyramid, the most frequently used methods in our study (MCQ and SAQ) were concentrated on lower levels of competence, while performance-based methods such as OSCE and Mini-CEX, which target higher levels of the pyramid, were less frequently applied. This imbalance highlights the need for broader implementation of workplace-based assessments to achieve a comprehensive evaluation of clinical competence.

In conclusion, some methods, including MCQ, short answer, OSCE, and Mini-CEX, were common methods used in the clinical assessment of medical students at KUMS over a five-year period. Given the advantages of these assessment methods for medical students as future physicians, other methods should be used to evaluate the clinical competency of medical students. Therefore, all faculty members and professors should learn assessment methods and use them appropriately.

5.1. Limitations

The study has some limitations that should be mentioned. Firstly, the study was retrospective in nature, so access to more information was limited. Secondly, we did not assess the reasons for using the assessment methods. Finally, due to the small number of some methods used, analytic statistics to assess the association between different variables could not be performed. Further research to overcome these limitations is recommended.