1. Background

It is estimated that Iran will require approximately sixty-three specialist doctors for every 100,000 people in 2026. Failure to meet this need could lead to a serious crisis for the country. Additionally, it is imperative to consider the distribution of expertise, as the number of graduates may not adequately meet future requirements in certain fields (1). While non-completion of capacity in certain specialized fields in Iran was rare in the past, for the first time in the academic year 2021, there has been a widespread reluctance to enter many specialized fields. This is a serious warning for health policymakers in Iran (2).

The decision to continue studying in various fields is a difficult and complicated issue as it directly impacts a person’s career and life. Moreover, the distribution and presence of graduate residents in different fields in society can lead to imbalances in the supply and demand of various specialties. These imbalances have been present in the past and are now becoming more serious (3). The issue directly influences the health status of the community and even impacts medical research. For instance, an increase in the number of graduates in the field of primary care has been linked to improved cardiovascular health, lower mortality rates, increased lifespan, and reduced rates of low birth-weight babies (3, 4).

Factors such as personal purpose, self-efficacy, and understanding outcome expectations have been identified as determinants of career development (5). Additionally, personal interest (6), institutional characteristics, medical school experiences, curricular features, demographic variables, specialty characteristics, lifestyle factors, and financial issues have been reported as predictors of specialty choices among medical students (7). Despite the multitude of factors that influence the career prospects of doctors, the main and consistent factor remains the personal interests of medical students, which may not always align with the medical needs of society (8).

In the past decade, there have been limited studies addressing the choices and views of medical students regarding their future planning in Iran. However, investigating which specialties medical students prefer for their future careers can be crucial for medical schools and health policymakers. Understanding these preferences can facilitate the development and optimization of curricula to inspire and guide students in their career choices (9). This approach aligns with the needs and priorities of health systems.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the level of interest in residency courses, immigration status, and the choice of specialty fields and influential factors among medical students in Guilan, Iran.

3. Methods

First, the protocol of this descriptive cross-sectional study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), and then it was performed at hospitals affiliated with GUMS from April to September 2023.

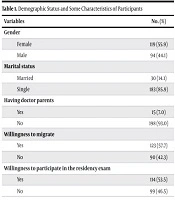

A total of 213 medical students in their final two years of study, ranging from the fifth to seventh years, who were willing to participate were consecutively enrolled in the study. The questionnaire was completed through a direct interview. The first part of the questionnaire comprised demographic and general information, including age, gender, marital status, desire to emigrate, willingness to participate in the residency entrance exam, and whether participants had parents who were doctors. The second part of the questionnaire included factors that could influence the choice of a specialization for a future career, such as hard work, income, work-life balance, the possibility of infection, exposure to patients, familiarity with the specialty field, on-call situation, duration of residency, personal interest, compatibility of the field with individual capabilities, and influence from attending and providing more services to the people. The third part of the questionnaire specified the participants’ top five preferred postgraduate specialties as well as the five specialties they definitely did not choose.

3.1. Statistics Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were utilized for the analysis. Additionally, a multinomial logistic regression model was applied to predict factors significantly affecting students’ preferences. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.2. Sample Size Calculation Method

In this study, the census method was used for the process of collecting data.

4. Results

A total of 213 eligible medical students with a mean age of 25.43 ± 1.66 years enrolled in the study. The demographic status and certain characteristics of the students have been summarized in Table 1. In terms of residency fields, dermatology was ranked highest by 50 (23.5%), followed by radiology with 25 (11.7%), cardiology with 48 (22%), ophthalmology and orthopedics with 36 (17%), and pathology with 16 (7%) as their top five choices, respectively. Conversely, orthopedics was the least preferred specialty with 57 (26.8%) students not choosing it, followed by infectious disease with 25 (11.7%), internal medicine with 21 (9.9%), emergency medicine with 8 (3.7%), and obstetrics and gynecology with 16 (7.5%).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 119 (55.9) |

| Male | 94 (44.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 30 (14.1) |

| Single | 183 (85.9) |

| Having doctor parents | |

| Yes | 15 (7.0) |

| No | 198 (93.0) |

| Willingness to migrate | |

| Yes | 123 (57.7) |

| No | 90 (42.3) |

| Willingness to participate in the residency exam | |

| Yes | 114 (53.5) |

| No | 99 (46.5) |

The reason why orthopedics was selected as both a top five preferred and also undesired field of residency was the influence of individual’s gender; male medical students preferred it as one of their first choices, while female participants had no desire for this specialty as a career and chose it as a non-preferred field. Indeed, the only significant variable that affected preferences (P = 0.001) and non-preferences (P < 0.001) for specialized fields was an individual’s gender. Other variables did not show any significant differences (Tables 2 and 3).

| First Five Specialty Preferences and Other Fields | Dermatology | Radiology | Cardiology and ENT | Ophthalmology, General Surgery and Orthopedic | Pathology and Psychiatry | Other Fields | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.347 | ||||||

| 25 years or less | 26 (21.5) | 10 (8.3) | 27 (22.3) | 23 (19.0) | 11 (9.1) | 24 (19.8) | |

| More than 25 years | 24 (26.1) | 15 (16.3) | 21 (22.8) | 13 (14.1) | 5 (5.4) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Gender | 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 8 (8.5) | 13 (13.8) | 25 (26.6) | 25 (26.6) | 7 (7.4) | 16 (17.0) | |

| Female | 42 (35.3) | 12 (10.1) | 23 (19.3) | 11 (9.2) | 9 (7.6) | 22 (18.5) | |

| Marriage status | 0.407 | ||||||

| Married | 10 (33.3) | 5 (16.7) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Single | 40 (21.9) | 20 (10.9) | 42 (23.0) | 34 (18.6) | 13 (7.1) | 34 (18.6) | |

| Having doctor parents | 0.850 | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (20.0) | |

| No | 47 (23.7) | 22 (11.1) | 46 (23.2) | 33 (16.7) | 15 (7.6) | 35 (17.7) | |

| Willingness to migrate | 0.809 | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (22.0) | 13 (10.6) | 28 (22.8) | 24 (19.5) | 8 (6.5) | 23 (18.7) | |

| No | 23 (25.6) | 12 (13.3) | 20 (22.2) | 12 (13.3) | 8 (8.9) | 15 (16.7) | |

| Willingness to participate in the residency exam | 0.979 | ||||||

| Yes | 29 (25.4) | 13 (11.4) | 24 (21.1) | 19 (16.7) | 8 (7.0) | 21 (18.4) | |

| No | 21 (21.2) | 12 (12.1) | 24 (24.2) | 17 (17.2) | 8 (8.1) | 17 (17.2) |

Abbreviation: ENT; ear, nose, and throat.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| First Five Specialty Non-preferences and Other Fields | Orthopedics | Infectious Diseases | Internal Medicine | Emergency Medicine | Obstetrics and Gynecology | Other Fields | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.460 | ||||||

| 25 years or less | 37 (30.6) | 16 (13.2) | 11 (9.1) | 3 (2.5) | 7 (5.8) | 47 (38.8) | |

| More than 25 years | 20 (21.7) | 9 (9.8) | 10 (10.9) | 5 (5.4) | 9 (9.8) | 39 (42.4) | |

| Gender | 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 16 (17.0) | 12 (12.8) | 7 (7.4) | 5 (5.3) | 2 (2.1) | 52 (55.3) | |

| Female | 41 (34.5) | 13 (10.9) | 14 (11.8) | 3 (2.5) | 14 (11.8) | 34 (28.6) | |

| Marriage status | 0.363 | ||||||

| Married | 6 (20.0) | 4 (13.3) | 4 (13.3) | 3 (0.10) | 1 (3.3) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Single | 51 (27.9) | 21 (11.5) | 17 (9.3) | 5 (2.7) | 15 (8.2) | 74 (40.4) | |

| Having doctor parents | 0.488 | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (13.3) | 9 (60.0) | |

| No | 54 (27.3) | 24 (12.1) | 21 (10.6) | 8 (4.0) | 14 (7.1) | 77 (38.9) | |

| Willingness to migrate | 0.196 | ||||||

| Yes | 29 (23.6) | 14 (11.4) | 16 (13.0) | 3 (2.4) | 12 (9.8) | 49 (39.8) | |

| No | 28 (31.1) | 11 (12.2) | 5 (5.6) | 5 (5.6) | 4 (4.4) | 37 (41.1) | |

| Willingness to participate in the residency exam | 0.959 | ||||||

| Yes | 33 (28.9) | 14 (12.3) | 10 (8.8) | 4 (3.5) | 9 (7.9) | 44 (38.6) | |

| No | 24 (24.2) | 11(11.1) | 11 (11.1) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.1) | 42 (42.4) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the independent variables that significantly predict the first five specialty field preferences. Gender, hard work, income, work-life balance, on-call status, and duration of residency were found to be significant in univariate analysis and included in the model (P < 0.001). Gender (P = 0.003) and on-call status (P = 0.001) were identified as significant predictors of choosing dermatology over other fields. Additionally, income was the only significant factor affecting medical students’ preference for radiology (P = 0.014), cardiology (P = 0.003), and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) (P < 0.001). Moreover, it was found that the choice of ophthalmology, general surgery, and orthopedic fields was inversely correlated with the factors of hard work (P = 0.026) and work-life balance (P = 0.027) (Table 4).

| Selected Fields and Predictors | β (se) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatology | |||

| Sex (male) | -1.59 (0.54) | 0.20 (0.07 - 0.59) | 0.003 |

| On-call status | 2.13 (0.61) | 8.41 (2.50 - 28.24) | 0.001 |

| Radiology | |||

| Income | 2.74 (1.11) | 15.55 (1.75 - 137.65) | 0.014 |

| Cardiology and ENT | |||

| Income | 1.71 (0.58) | 5.58 (1.78 - 17.43) | 0.003 |

| Ophthalmology, general surgery and orthopedic | |||

| Hard work | -1.45 (0.65) | 0.23 (0.06 - 0.84) | 0.026 |

| Work-life balance | -1.26 (0.57) | 0.28 (0.09 - 0.86) | 0.027 |

| Pathology and psychiatry | - | - | - |

Abbreviation: ENT; ear, nose, and throat.

5. Discussion

A recent study highlighted the alarming situation of medical residents in Iran. Improving the conditions with adequate salaries and adjusted shift hours could motivate Iranian medical doctors to enter the residency programs (10). Indeed, for better performance of medical students, special attention must be paid to their academic activities, their motivational factors, and the mismatch between their living and educational environments (11).

In the present study, over half of the participants expressed interest in taking the residency exam, while more than 50% desired to immigrate. Gender, on-call status, income, hard work, and work-life balance were identified as significant predictors of medical students’ top five preferences for specialty fields. Many medical students in this study were not willing to participate in the residency exam, while previous studies by Salehian et al., Anand and Sankaran, and Kataria showed that almost all students expressed a desire to continue their education (12-14). In addition, burnout during the general medicine course could justify the unwillingness to continue studying in a specialized field (2, 15).

In this study, female gender had a significant impact only on the choice of dermatology specialty, approximately five times more than males. These findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the influence of gender on specialty choice. However, it is worth noting that in other countries, dermatology is not a high priority for physicians, even among females (16). Salehian et al. also found that dermatology was among the top five preferences of medical students, but only the choice of urology was significantly influenced by participants’ gender (12). Conversely, Alizadeh et al. supported our findings, indicating that dermatology was the most popular choice among female medical students (17). It seems that the high ranking of dermatology as a specialty in Iran could be attributed to the high demand for cosmetic procedures (18). However, our study revealed that the on-call situation is another significant determinant in choosing dermatology as a specialty field.

In our study, income was found to be a significant factor in preference for certain residency fields such as radiology, cardiology, and ophthalmology. This finding is consistent with previous research that has also identified income as a major influencing factor in choosing a specialized field (16, 17, 19, 20). However, it is notable that while income influences medical students’ choices, it often ranks lower compared to other factors such as personal interests and work-life balance (12, 14, 21-23). The preference for fields with less hard work, fewer on-call demands, and better work-life balance, combined with income concerns in other fields, poses a challenge for the healthcare system in terms of the lack of a sufficient number of specialists in some other fields (2).

In our study, the significant factors influencing the choice of specialized fields such as ophthalmology, general surgery, and orthopedics were lack of attention to the difficulty of the job and the balance between work and life. This suggests that students who did not prioritize these influencing factors tended to choose these specializations. Studies show that there are external factors distinct from personality traits associated with specialty choices, and the help of counselors is essential (24). Improving their emotional and spiritual intelligence is also important (25). Another study showed that surgery was the first specialty choice, motivated by higher income. Medical students stated that they need mentoring programs (26). A similar finding was observed in the study of Grasreiner et al. in terms of the surgical specialties (23). Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of considering the balance between work and life as significant factors in choosing a specialized field (8, 12, 13, 16, 19-21, 27). It is crucial to confirm that recognizing the importance of lifestyle factors presents a challenge in terms of providing human resources in specialized fields that may not be attractive to medical students and doctors from this perspective (16).

Our findings highlight that the lack of attention to the issue of quality of life is particularly relevant in surgical specialties. It is highly probable that individuals who choose these fields have expectations of achieving desirable income, which may offset concerns about the demanding nature of the work and the imbalance between work and personal life.

In general, it seems that medical students in Iran suffer from a lack of motivation in terms of continuing education and entering residency programs. Since specialty field preferences are influenced by several factors, including personal purpose, perceived familial support, socio-economic status and attitudes of individuals, self-efficacy, personal interest, institutional characteristics, medical school experiences, lifestyle factors, demographic variables, specialty characteristics, and financial issues, the results from other areas cannot be generalized. The inconsistency of findings in the studies is due to the aforementioned influential factors.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of our study indicate that a significant proportion of individuals were not interested in continuing further education and were inclined to emigrate. The fact that income appears to be a predictive factor for certain fields, coupled with emergency medicine being among the least preferred specialties, underscores the significance of investigating the underlying causes and prioritizing efforts to address this issue within the healthcare system. Gender and on-call situation were significant factors in choosing dermatology specialty. On the whole, the warning situation of residency was highlighted in this study, and attempts should be made to improve the conditions such as adequate salaries and adjusted shift hours. More comprehensive studies across multiple universities offer a valuable opportunity to gather substantial information and provide policymakers with insights on how to more effectively enhance the residency selection process.

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

The strength is that it was a valuable work, given the current medical situation in Iran. Limitations were that a number of medical students refused to participate in the study and complete the checklist, despite receiving explanations about the purpose of this study. It is conceivable that there were more unsatisfied people among them. In addition, we enrolled medical students of the last two years in this survey, but there was a significant difference between the attitude of medical students in their first month of internship with no experience compared to those in their last month of internship who had completed all courses.