1. Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous hematopoietic malignancy with various subtypes defined by the genetic and molecular characteristics of the leukemia cells, characterized by the rapid expansion of undifferentiated myeloid precursors, resulting in disturbed normal hematopoiesis (1, 2). Accordingly, leukemic cells exhibit various manifestations, including morphological, immunophenotypes, genetic, and cellular metabolomic profiles (3-5). The significance of identifying genetic abnormalities in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of hematological malignancies, such as AML, is now well-documented (6). In this regard, the World Health Organization (WHO) and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) guidelines rely on cytomorphology, immunophenotyping, cytogenetics, and molecular genetics (7). The patient’s genetic profile has a significant role in the diagnosis of hematological malignancies. The RUNX1-RUNX1T1 translocation is among the most prevalent, detected in approximately 15% of AML cases, and is associated with a favorable prognosis (8, 9). Three to five percent of AML patients who are positive for RUNX1-RUNX1T1 exhibit three-way breakpoints involving several chromosomes, including 2q, 17p, and 18p (10, 11).

The PML-RARα transcript is detected in 8 - 10% of AML patients, specifically in those with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Among the three main breakpoints producing different variants of t(15;17), bcr1 and bcr3 are detected in 90 - 95% of APL patients (12, 13). Approximately 8 - 10% of AML cases are characterized by inv(16)(p13.1q22) [t(16;16) (p13.1;q22)]/CBFB-MYH11. Among the different variants of CBFB-MYH11, type A is detected in more than 85% of patients with a positive result (13, 14).

Over time, several diagnostic methods have emerged and improved to detect clinically significant genetic alterations. These methods differ from one another in terms of time, cost, availability, sensitivity, specificity, and the minimum required sample size (15). The accessibility and rapid reporting, alongside favorable sensitivity and specificity, have introduced molecular methods as the main tool in AML diagnostic practices (16, 17). Although karyotyping is one of the most pioneering methods for cytogenetic analysis, it is no longer popular due to its time-consuming and challenging process (18). Similarly, the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) method is not widely used because it requires unique probes and has a high workload burden (19, 20). Innovative techniques like next-generation sequencing and single-cell assays are emerging and offering detailed insights in the context of leukemia. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) can be used for AML patients with recurrent translocations, profiling subpopulations, tracking clonal evolution, and detecting prognostic biomarkers (21). Due to amplification-induced noise, the necessity of joint cell analysis, and the substantial data volume, fusion detection in scRNA-seq remains a major challenge. A statistical and deep-learning model called scFusion showed acceptable performance for T cell receptor (TCR) gene recombination and multiple myeloma subclones with IgH-WHSC1 fusions (22). Digital PCR (dPCR) assays now enable precise, absolute quantification of fusion transcripts for measurable residual disease (MRD) monitoring, with excellent reported limits of detection, especially for deep molecular response quantification in chronic myeloid leukemia (23).

Although new methods are emerging, real-time PCR remains a leading, widely accessible diagnostic tool for identifying leukemic translocations. Its advantages include quick results, the ability to quantify genetic abnormalities, and the detection of cryptic translocations (14, 24). Additionally, its DNA amplification improves sensitivity by up to 6 - 10 times, making it applicable for detecting MRD (7, 24).

While developing novel diagnostic techniques is beneficial, upgrading the known ones is also valuable (25). Simultaneous amplification and detection of multiple target DNA sequences within one PCR reaction is a variant of real-time PCR known as multiplex real-time PCR (26). The SYBR Green real-time PCR assay is a time-consuming and cost-effective screening method that detects a translocation in approximately 4 hours via the melting temperature (Tm). Besides saving time and lab resources, multiplexing minimizes the contamination risks and inter-assay variability (27).

2. Objectives

In the present study, we developed a screening assay applicable in multiplex formats, using the same materials, instruments, and conditions for screening the three most frequent translocations: RUNX1-RUNX1T1, PML-RARα, and CBFB-MYH11.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

The EDTA samples were obtained from bone marrow or peripheral blood aspirates of 50 newly diagnosed and de novo AML patients. The cohort consisted of 29 males and 21 females, with a median age of 48 years, ranging from 20 to 65 years. Diagnoses were determined based on a combination of pathology and immunotyping results. al approval was waived by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.486).

3.2. Primers

The primer sets recommended by the Europe Against Cancer (EAC) program were used in the present study (28) (Appendix 4 in Supplementary File). The assay included a total of seven primers, consisting of forward and reverse primers for RUNX1-RUNX1T1, forward and reverse primers for CBFB-MYH11, type A, and forward and reverse primers for PML-RARα, bcr1. For PML-RARα, bcr3, a forward primer was used in combination with the reverse primer shared with PML-RARα, bcr1. NCBI-Blast was employed to assess the specificity of the primers. Various multiplexing tools were tested to evaluate the primer pooling. Additionally, the risk of primer dimer and secondary structure formation was inspected. The product sizes of the SYBR Green real-time PCR reaction ranged from 97 to 147 bp, and the primer lengths were between 17 and 22 bp, with Tm of 57 to 63°C and GC contents between 45.5% and 64.7%. The primers were ordered in standard desalting quality.

3.3. RNA Extraction and Complementary DNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Pishgam Biotech Co., Tehran, Iran). The RNA purity was assessed by the ratio of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. Gel electrophoresis was performed to assess the RNA integrity. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was carried out in a 20 μL reaction mixture containing 1× reaction buffer, 500 μmol/L each dNTP, 5 μmol/L Oligo(dT) primers, 5 μmol/L random hexamer primers, 2 μg total RNA template, and 10 U/μL reverse transcriptase, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The reverse transcription reaction was incubated at 25°C for 10 minutes and then at 50°C for 60 minutes. The enzyme was inactivated at 80°C for 5 minutes.

3.4. Multiplex Real-time PCR Assay

Multiplex real-time PCR was conducted using the ABI StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) with 48-well plates in a 20 μL reaction volume. ABL, used as the reference gene, was amplified in separate parallel reactions because its Tm (82.5°C) was close to that of RUNX1-RUNX1T1. UltraPure nuclease-free water was used for all amplification processes and non-template controls (NTCs) to minimize the risk of contamination. Negative cDNA control (NC) and non-template control (NTC) were included in all real-time PCR reactions. Plasmid DNAs of RUNX1-RUNX1T1, PML-RARα (bcr1, bcr3), were kindly provided by NovinGene (Tehran, Iran). Additionally, cDNAs synthesized from the positive patients were applied to all four targets.

For each target gene, the temperature gradient PCR was conducted using PeqSTAR 2X Gradient Thermocycler (PEQLAB Biotechnologie, Germany), with an annealing temperature range from 58.0 to 63.0°C as follows: Ten μL master mix (Ampliqon, Denmark), 7.2 μL nuclease-free water (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Iran), 0.4 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), and two μL of cDNA.

Then, a singleplex real-time PCR was performed for all four targets. After ensuring the successful setup, primers were combined to design a two-plex assay. In this approach, targets were multiplexed in pairs, resulting in the development of all two-plex assays. Then, a three-plex and a four-plex real-time PCR were performed. In all multiplex formats (6 two-plex formats, four forms of three-plex formats, and a four-plex format), a singleplex was performed in parallel within the same run to compare the cycle threshold (Ct) and Tm values. Multiplex reactions were carried out in a total volume of 20 µL, which included 10 µL of 2× SYBR Green master mix, 2 µL of cDNA template, and nuclease-free water to reach the final volume. Primer volumes for each 20 µL reaction were as follows: RUNX1-RUNX1T1 forward 0.6 µL and reverse 0.6 µL; CBFB-MYH11 forward 0.7 µL and reverse 0.7 µL; PML-RARα bcr1 forward 0.5 µL; bcr3 forward 0.5 µL; and common reverse ENR962 1.0 µL. Since primer stocks are at 10 µM, the final concentrations per primer were: RUNX1-RUNX1T1 300 nM each; CBFB-MYH11 350 nM each; PML-RARα, bcr1 forward 250 nM; PML-RARα, bcr3 forward 250 nM; and common reverse 250 nM. The remaining volume was filled with nuclease-free water.

For four-plex real-time PCR, various PCR programs and reaction volumes were tested. The cycling program was conducted as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 15 seconds. Melting curve analysis was applied in the same instrument.

3.5. Criteria for Positive Sample Identification

A sample was considered positive if it met the following criteria: (A) a typical "S-shape" amplification curve above the threshold level; (B) a single, narrow peak obtained from melting analysis with a defined melting Tm value based on the Tm of positive controls (SD ± 1°C); (C) an expected single band on agarose gels; (D) no amplification in the NTC from the same run; and (E) positive amplification of ABL.

3.6. Assay Validation

In this method, the specificity was assessed using the following four strategies: (A) initial screening of primers with BLAST; (B) examination of non-AML individuals (30 healthy individuals; (C) melt-curve analysis; and (D) gel electrophoresis. Repeatability and reproducibility were measured in five replicates within the same run (intra-assay) and across three different runs (inter-assay).

3.7. Comparison Between Multiplex Real-time PCR and Singleplex Real-Time PCR

Clinical testing was performed in parallel on 50 newly-diagnosed samples to compare the singleplex and multiplex real-time PCR methods, identifying whether the singleplex methods can be replaced by the multiplex one.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.1), incorporating the tidyverse, ggpubr, and pwr packages. Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Given the small sample sizes, formal normality assessments were not performed; paired comparisons between singleplex and multiplex assays utilized non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, with asymptotic approximations applied for ties or zeros. Consequently, descriptive statistics, including means and observed trends, were employed.

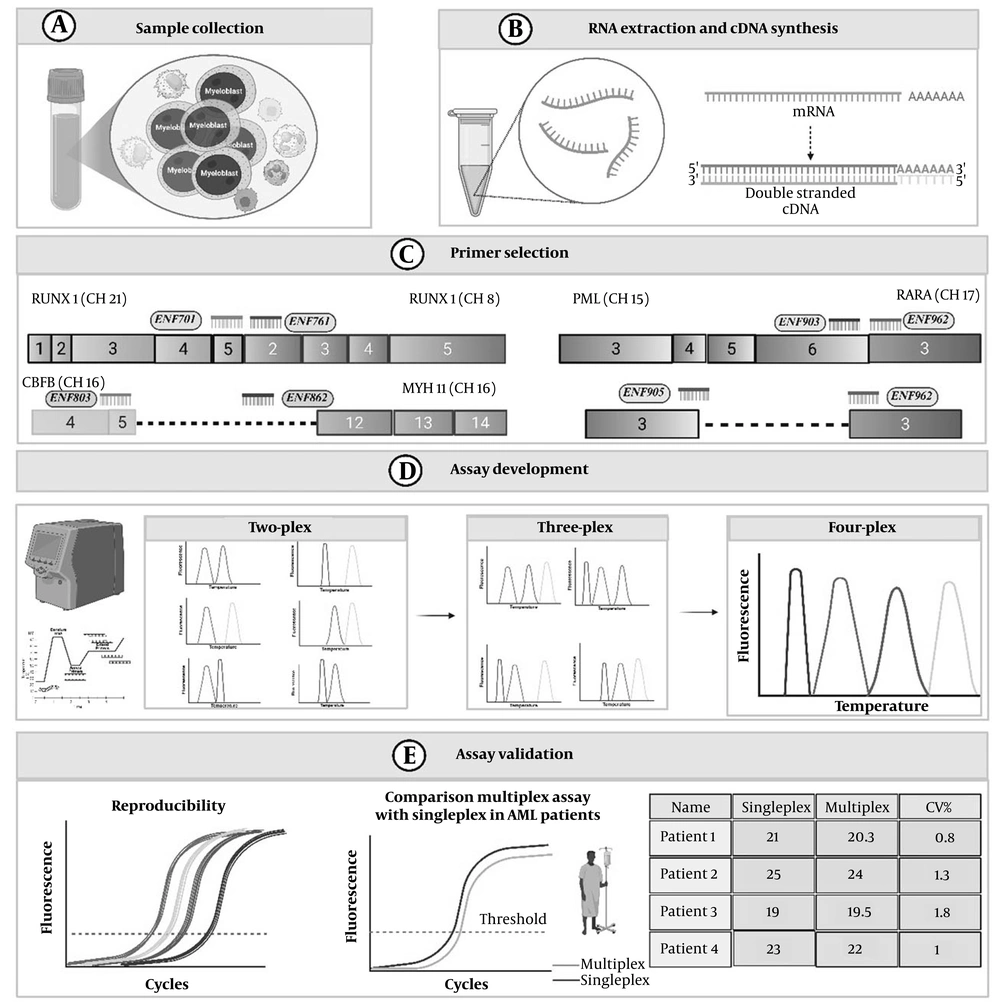

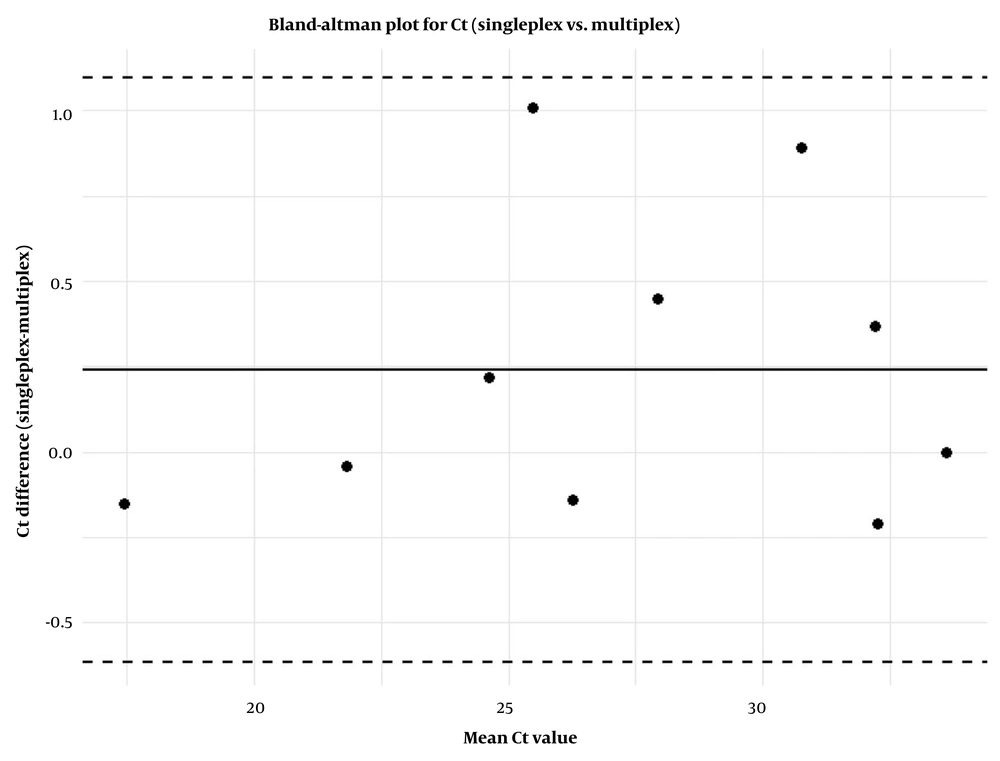

The agreement between singleplex and multiplex methods was assessed using Bland-Altman plots, which provided the mean differences and limits of agreement (± 1.96 SD). Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d (mean difference divided by SD), and post-hoc power analyses were conducted based on a non-central t-distribution (two-sided, α = 0.05). Sensitivity and specificity were estimated using Clopper-Pearson exact 95% binomial CIs. Coefficient of variation (CV) were determined as (SD/mean) × 100%, with NA assigned for mean differences of zero or sample sizes of n = 1. P-values are reported to three decimal places, and results from subgroups with n < 5 are interpreted cautiously due to limited statistical power. All analyses were benchmarked against comparable multiplex assay studies, such as those by Dolz et al. (29). A schematic overview of the method is illustrated in Figure 1.

Schematic overview of development, optimization, and validation of the multiplex SYBR Green real-time PCR assay for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) translocations. A, sample collection; B, RNA extraction and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis; C, primer selection: Europe Against Cancer (EAC)-recommended primer sets were selected; D, primers combined sequentially to establish two-plex, three-plex, and four-plex assays, with all targets showing distinct melting temperature (Tm) values (> 1°C separation); E, assay validation: The assay demonstrated reproducibility with acceptable inter- and intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV), and comparison with singleplex PCR showed minimal, non-significant differences in ΔCt and ΔTm values (The figure is created by BioRender).

4. Results

4.1. Optimization of Multiplex Real-time PCR

- Cycle number: Some negative controls exhibited PCR amplification curves with Ct values greater than 35. Their Tm (ranging from 61°C to 74°C) and electrophoresis band confirmed the nature of their primer-dimer artifacts. To maximize assay sensitivity and minimize possible artifact amplification, 35 cycles were chosen as the optimal number of cycles (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

- Primer concentration: Various primer concentrations were evaluated to determine the most suitable amount for each. The best final concentrations were as follows: RUNX1-RUNX1T1 primers: 300 nM, PML-RARα, bcr1, and bcr3 primers: 250 nM, and CBFB-MYH11 primers: 350 nM.

- Annealing step: The annealing temperature of 60°C was associated with the lowest Ct, indicating it was the ideal annealing temperature in supporting specific amplification.

- Extension step: Compared to the 2-step PCR, the 3-step, including an extension step, resulted in a sharper melt curve. Evaluating the extension time of 15, 20, and 30 seconds for this step indicated that increasing the extension time did not improve the amplification reaction. Considering the length of the target amplicons ranged from 97 to 147 bp and polymerase extension rates, which are typically 10 to 45 nucleotides per second (30), the condition of 72°C for 15 seconds showed the best results for the extension step.

- Reaction components: The magnesium ion is the key parameter affecting the Ct value. MgCl2 titrations were performed to achieve the lowest Ct values. However, no significant improvement was observed. These results indicate that adjusting magnesium concentration does not significantly enhance the overall performance of the multiplex system.

4.2. Assay Validation

This technique met all four mentioned criteria for specificity. The Tm values differed by at least 1°C in all four translocations (Table 1). The multiplex SYBR Green real-time PCR assay effectively amplified all four target fusion genes (RUNX1-RUNX1T1, PML-RARα, bcr1, and PML-RARα, bcr3, and CBFB-MYH11) without interference in their respective melt curves (Appendices 2 and 3 in Supplementary File). The assay demonstrated 100% specificity (95% CI: 91.2% - 100.0%, Clopper-Pearson), with no false positives observed in negative controls or among the 40 patients without translocations. Sensitivity was also 100% (95% CI: 69.2% - 100.0%), accurately detecting all 10 positive cases within the 50-patient cohort (5 RUNX1-RUNX1T1, 1 PML-RARα, bcr1, 2 PML-RARα, bcr3, 2 CBFB-MYH11), aligning with the 100% accuracy reported by Dolz et al. (29) for analogous fusion gene detection.

| Translocation | Mean ± SD of Tm (°C) |

|---|---|

| t(8;21) (q22,q22)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 | 82.01 ± 0.145 |

| t(15;17) (q24;q12)/PML-RARα, bcr1 | 87.57 ± 0.147 |

| t(15;17) (q24;q12)/PML-RARα, bcr3 | 86.07 ± 0.126 |

| t(16;16)(p13.1q22)/CBFB-MYH11, type A | 83.09 ± 0.188 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; Tm, melting temperature.

Reproducibility was evaluated through intra- and inter-assay CV for Ct and Tm values (Table 2). Intra-assay CVs for Ct ranged from 0.68% to 1.12% (means: 19.38 - 27.20), and for Tm from 0.15% to 0.50% (means: 81.95 - 87.77), indicating high consistency within runs. Inter-assay CVs ranged from 0.22% to 1.02% for Ct and 0.08% to 0.57% for Tm, reflecting robust reproducibility across runs. For example, RUNX1-RUNX1T1 showed an intra-assay Ct mean of 19.38 ± 0.21 and Tm mean of 81.95 ± 0.29, with inter-assay values of 19.40 ± 0.19 and 81.96 ± 0.34, demonstrating minimal variability.

| Gene | Intra-assay Ct Mean (95% CI) | Intra-assay Ct CV (%) | Inter-assay Ct Mean (95% CI) | Inter-assay Ct CV (%) | Intra-assay Tm Mean (95% CI) | Intra-assay Tm CV (%) | Inter-assay Tm Mean (95% CI) | Inter-assay Tm CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUNX1-RUNX1T1 | 19.38 (19.20 - 19.56) | 1.12 | 19.40 (19.24 - 19.56) | 1.02 | 81.95 (81.66 - 82.24) | 0.36 | 81.96 (81.62 - 82.30) | 0.41 |

| PML-RARα, bcr1 | 24.68 (24.50 - 24.86) | 0.81 | 24.51 (24.35 - 24.67) | 0.75 | 87.77 (87.59 - 87.95) | 0.25 | 87.80 (87.72 - 87.88) | 0.08 |

| PML-RARα, bcr3 | 24.19 (24.00 - 24.38) | 1.12 | 24.00 (23.93 - 24.07) | 0.22 | 86.12 (85.83 - 86.41) | 0.50 | 86.29 (85.94 - 86.64) | 0.57 |

| CBFB-MYH11 | 27.20 (27.02 - 27.38) | 0.68 | 27.17 (27.04 - 27.30) | 0.50 | 83.10 (82.98 - 83.22) | 0.15 | 82.96 (82.86 - 83.06) | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; CI, confidence interval; CV, coefficient of variation; Tm, melting temperature.

4.3. Comparison Between Multiplex Real-Time PCR and Singleplex Real-Time PCR

In 50 AML patients, 5 cases of RUNX1-RUNX1T1, 2 cases of CBFB-MYH11, type A, 1 case of PML-RARα, bcr1, and 2 cases of PML-RARα, bcr3 were detected. Validation in 50 AML patients demonstrated strong concordance between singleplex and multiplex assays using Bland-Altman analysis (mean ΔCt: 0.24, limits of agreement: -0.61 to 1.09), as depicted in Figure 2 that shows the distribution of differences, with most data points falling within the limits of agreement, showing good consistency between the methods. A slight bias toward positive differences at higher mean Ct values suggests minor systematic variation that could be explored in larger cohorts. Mean ΔCt ranged from -0.125 (bcr3) to 0.380 (RUNX1-RUNX1T1), with Wilcoxon P-values from 0.106 to 1.000, indicating no significant differences (Table 3). Mean ΔTm ranged from 0.150 (CBFB-MYH11) to 0.325 (bcr3), with P-values from 0.174 to 1.000. Notably, multiplex assays often produced lower Ct values.

| Gene | No. | ΔCt Mean | Ct SD | Ct CV (%) | Ct P-Value | ΔTm Mean | Tm SD | Tm CV (%) | Tm P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUNX1-RUNX1T1 | 5 | 0.380 | 0.421 | 111.0 | 0.106 | 0.240 | 0.227 | 94.8 | 0.174 |

| PML-RARα, bcr1 | 1 | 0.000 | NA | NA | NA | 0.000 | NA | NA | NA |

| PML-RARα, bcr3 | 2 | -0.125 | 0.120 | 96.2 | 0.371 | 0.325 | 0.247 | 76.1 | 0.371 |

| CBFB-MYH11 | 2 | 0.375 | 0.728 | 194.0 | 1.000 | 0.150 | 0.212 | 141.0 | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; Tm, melting temperature; NA, not available.

5. Discussion

Enhancing the simplicity and speed of diagnostic tests is an undeniable aspect of molecular diagnosis in the laboratory. Although novel diagnostic methods are considered revolutionary advances, their accessibility remains limited for all laboratories. Therefore, modifications to conventional methods are still appreciated to enhance their cost-effectiveness, time efficiency, and accessibility. The single amplification method will be replaced by the multiplex assay, as it is less susceptible to pipetting errors and minimizes the hands-on time, offering cost and time benefits. Although multiplex real-time PCR appears straightforward, some critical factors must be considered. A challenge faced by all multiplex methods is competition, a common issue, especially related to viral detection. In contrast to viral or pathogenic multiplexing approaches, detecting two translocations in a single individual is extremely rare (31). This lack of competition among the targets raises interest in conducting multiplex assays for screening fusion transcripts.

In the current assay, Ct values in multiplex real-time PCR assays conducted on positive samples overlap almost exactly with those from the corresponding singleplex assay, indicating comparable sensitivity of the current multiplex approach. Interestingly, there were several cases where the Ct value from the multiplex was lower than that from the singleplex. Similarly, this phenomenon has been reported in various other multiplex assays within non-hematological fields, particularly in viral detection (32-34). Quality-control studies documented low-frequency discrepancies, particularly at minimal transcript concentrations. Specifically, false-negative rates of up to 12% and false-positive frequencies ranging from 2% to 9.7% were observed, depending on the fusion type and dilution level, especially for CBFB-MYH11 and PML-RARα, bcr1, at 10-4 dilutions (28). In the current study, no false-positive or false-negative results were detected for any of the analyzed fusion transcripts. This outcome can be attributed to our additional verification steps, which include confirmation of amplification specificity through Tm analysis and visualization of the corresponding bands on agarose gel electrophoresis. These complementary criteria minimized the risk of false signal interpretation and strengthened the reliability of our results.

Another critical factor in developing multiplex assays is the number of cycles, as Ibrahim et al. suggested a false positive of NTC after 37 cycles (35). Siraj et al. defined 32 cycles as optimal to avoid primer-dimer formations (36). Successful SYBR Green multiplex assays are typically achieved using fewer amplification cycles. Optimization should begin with a low cycle number and be gradually increased to balance sensitivity and specificity (37). More than 35 cycles increase the probability of smears and false-positive results (26). Therefore, 35 cycles were selected as an optimal number of cycles for our multiplex PCR screening assay.

Our approach could provide several advantages as a practical first-level screening strategy. First, our results showed the adaptability of singleplex primers for multiplex assays. The specificity and sensitivity of primers are crucial for a successful assay; therefore, we used previously validated primers in our study. Because these primers also perform well in singleplex assays, they remain suitable for follow-up testing. This approach simplifies molecular diagnostics by reducing the number of reagents and eliminating the need for complex primer redesign (19). Therefore, using validated primers is more rational than insisting on designing novel primers.

Another benefit of our method was its cost-effectiveness, as the application of intercalating dyes significantly reduces the cost of real-time PCR. Additionally, sample throughput is increased in multiplex PCR, as four variants are evaluated simultaneously with a single control. The assay provided results from a single 20 µL reaction while simultaneously screening for four major prognostic translocations. A negative result for all four targets alerts clinicians that the patient may lack favorable-risk cytogenetics, prompting further molecular investigation (37). However, further investigations are necessary for other mutations and less prevalent translocations.

Furthermore, as the screening of four common translocations was performed by a sole real-time PCR instrument and a single technician, the processing time will be reduced to five hours from sampling, including one hour for RNA extraction, 1.5 hours for cDNA synthesis, and 2.5 hours for the multiplex assay. Moreover, the results are easy to interpret, as four unique Tm values were identified and validated for each target. Although we found primer-dimer artifacts, other studies have also reported this undesired amplification (35, 36). Hence, a possible limitation of this screening method is the weak amplification of NTC due to primer-dimer formation, which often has a different Tm value than the four targets, though this can be eliminated by decreasing the number of cycles. Furthermore, this method is not capable of detecting all variants of CBFB-MYH11 and bcr2. It is worth noting that during the assay development phase, we also evaluated the inclusion of the PML-RARα, bcr2 in a five-plex assay. Although amplification was successful, the Tm of bcr2 (87.8°C) overlapped with that of bcr1, leading to indistinct melting profiles. Therefore, more technical work is required to improve it. Although advanced methods such as dPCR and sequencing offer single-cell resolution and greater analytical depth, our multiplex assay remains a practical, accurate, and cost-effective first-line screening tool.

5.1. Conclusions

Although developing new diagnostic technologies is important in the field of leukemia, ongoing improvement and refinement of current methods are equally essential. Overall, this assay offers a fast, reliable, and cost-effective molecular method for screening three common translocations in AML simultaneously. By allowing quick detection of these favorable genetic alterations, it provides timely risk assessment and supports informed clinical decisions for AML patients.