1. Context

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by segmental inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. According to the global burden of disease (GBD) data (1), China harbors the largest proportion of IBD patients worldwide, and this number is expected to rise further by 2030. The highest incidence rates of CD are reported in North America (20.7 per 100,000) and Europe (12.7 per 100,000) (2). Epidemiological surveys conducted in China between 2010 and 2011 indicate an incidence rate of CD ranging from 0.13 to 1.09 per 100,000 individuals (3). Another study estimates that this incidence rate has nearly doubled over the past three decades (4).

The pathological hallmark of CD is transmural inflammation, with intestinal fibrosis being a key pathophysiological process. This condition can lead to severe complications such as intestinal strictures and obstruction, significantly impairing patients' quality of life and increasing the burden on healthcare systems. It is estimated that approximately 30 - 50% of CD patients will develop intestinal fibrosis within 10 years of diagnosis (5).

Although various studies have explored the mechanisms underlying intestinal fibrosis in CD, its exact pathogenesis and effective prevention and treatment strategies remain elusive. Therefore, this review systematically examines the progress in understanding intestinal fibrosis in CD and explores both conventional and integrative medicine approaches to prevention and treatment (Table 1).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Original research or meta-analysis | Non-English/non-Chinese publications |

| Focus on CD-related intestinal fibrosis | Case reports or editorials |

| Human/animal model studies | Studies without fibrosis assessment |

| TCM/Western medicine interventions | Duplicated data or incomplete outcomes |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn's disease; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

2. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Intestinal Fibrosis in Crohn's Disease

2.1. Inflammatory Response and Fibrosis

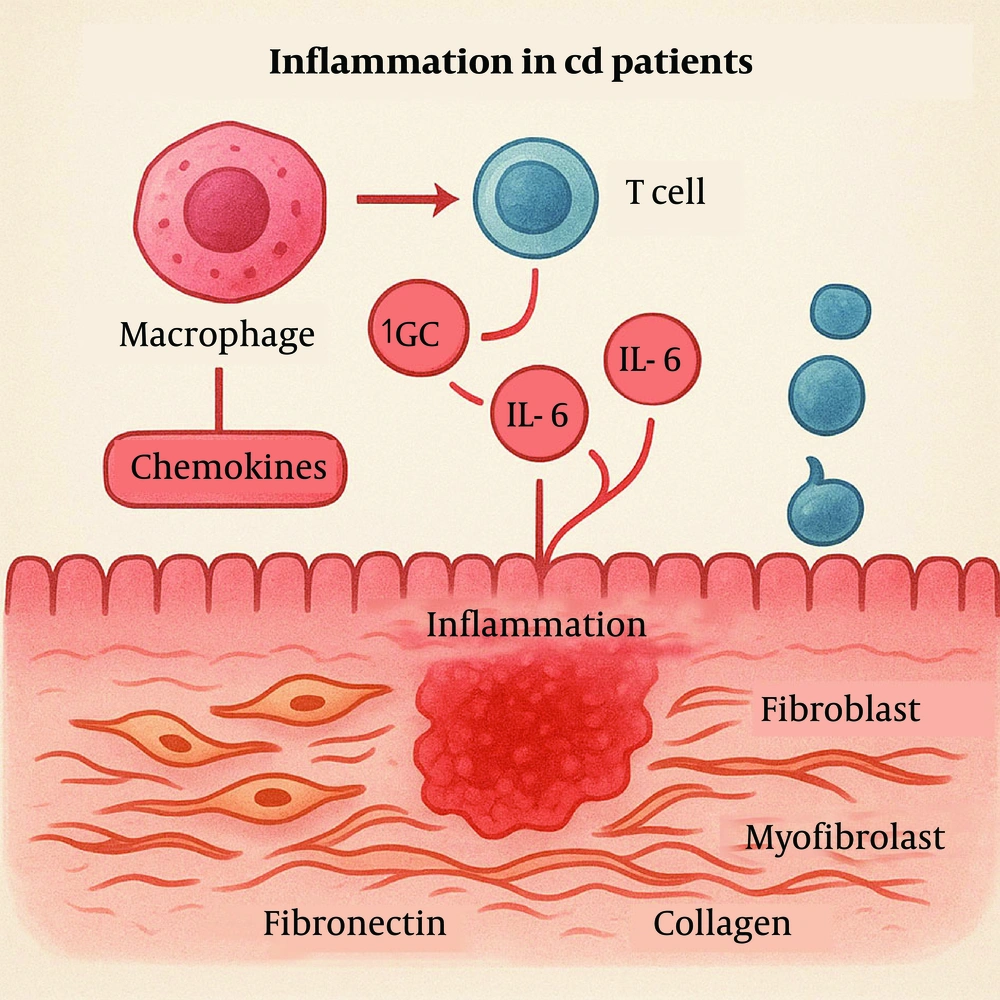

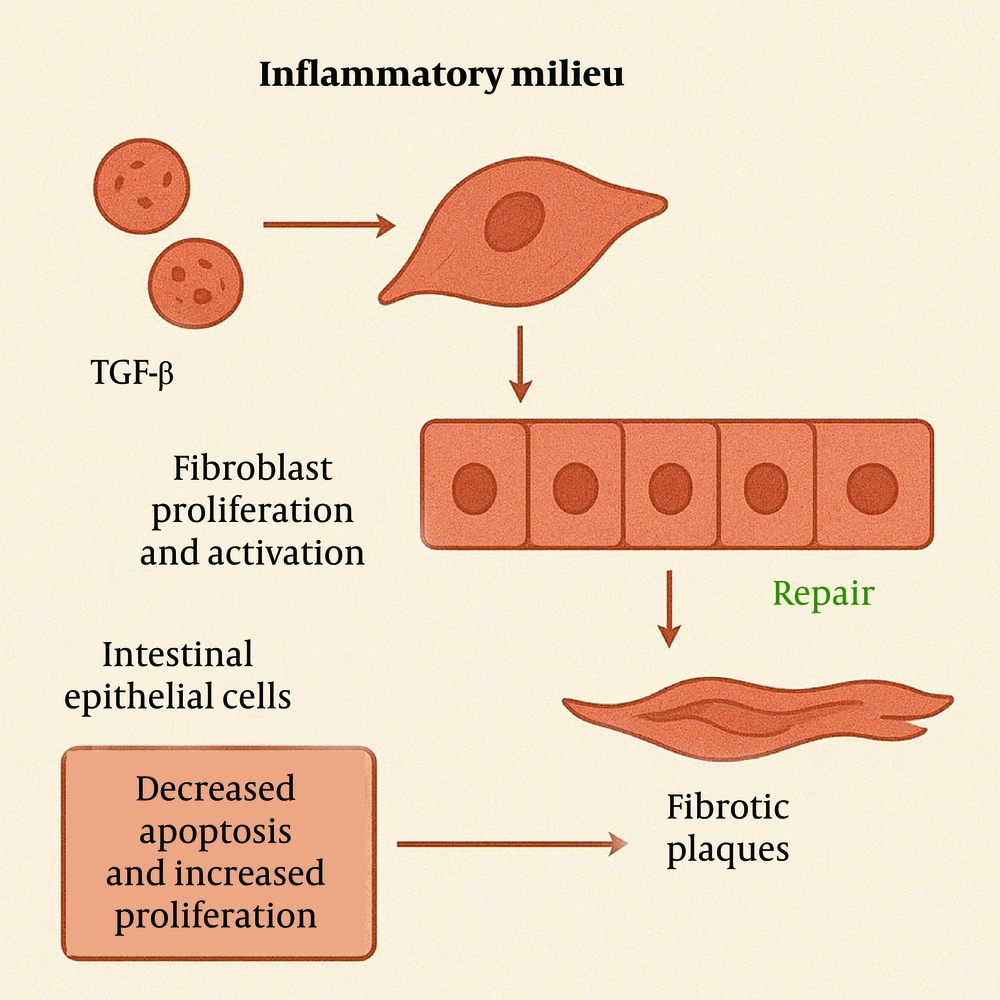

In CD patients, aberrant immune activation drives intestinal inflammation, characterized by excessive cytokine release [e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6)] and recruitment of inflammatory cells. The inflammatory response involves the release of various cytokines, such as TNF-α, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and chemokines, which attract and activate inflammatory cells, including macrophages and T-cells (6). Pro-inflammatory factors not only initiate localized inflammation but also stimulate fibroblasts to transform into myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts secrete large amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as collagen and fibronectin, resulting in the accumulation of fibrous tissue (Figure 1) (7).

2.2. Activation of Fibroblasts and Extracellular Matrix Deposition

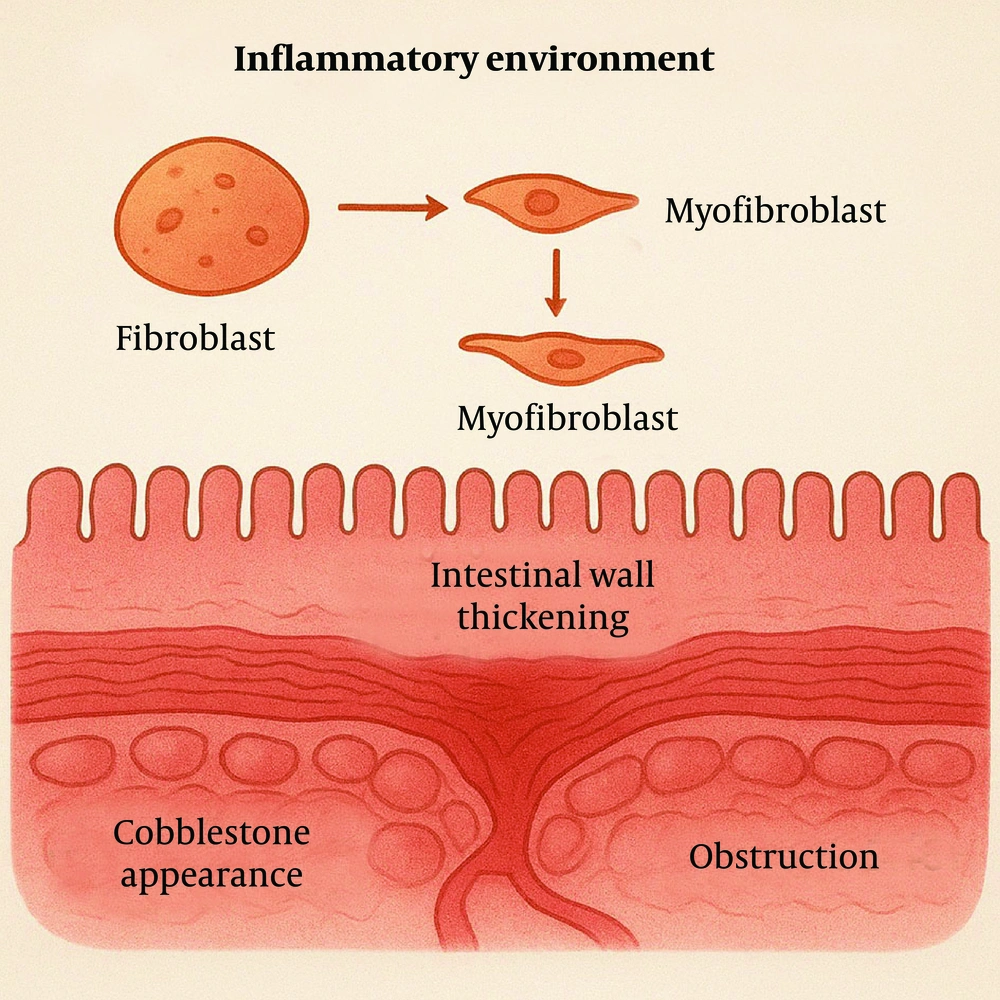

In an inflammatory environment, fibroblasts are activated and differentiate into myofibroblasts, a process typically mediated by transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) (6). Myofibroblasts possess the ability to synthesize significant amounts of ECM, including collagen types I, III, and V. Aberrant ECM deposition leads to intestinal wall thickening, with hyperplasia of the muscularis mucosa and propria, giving rise to the characteristic "cobblestone" appearance (8). These structural changes ultimately result in intestinal stricture and, in severe cases, obstruction (Figure 2).

2.3. Imbalance Between Apoptosis and Proliferation

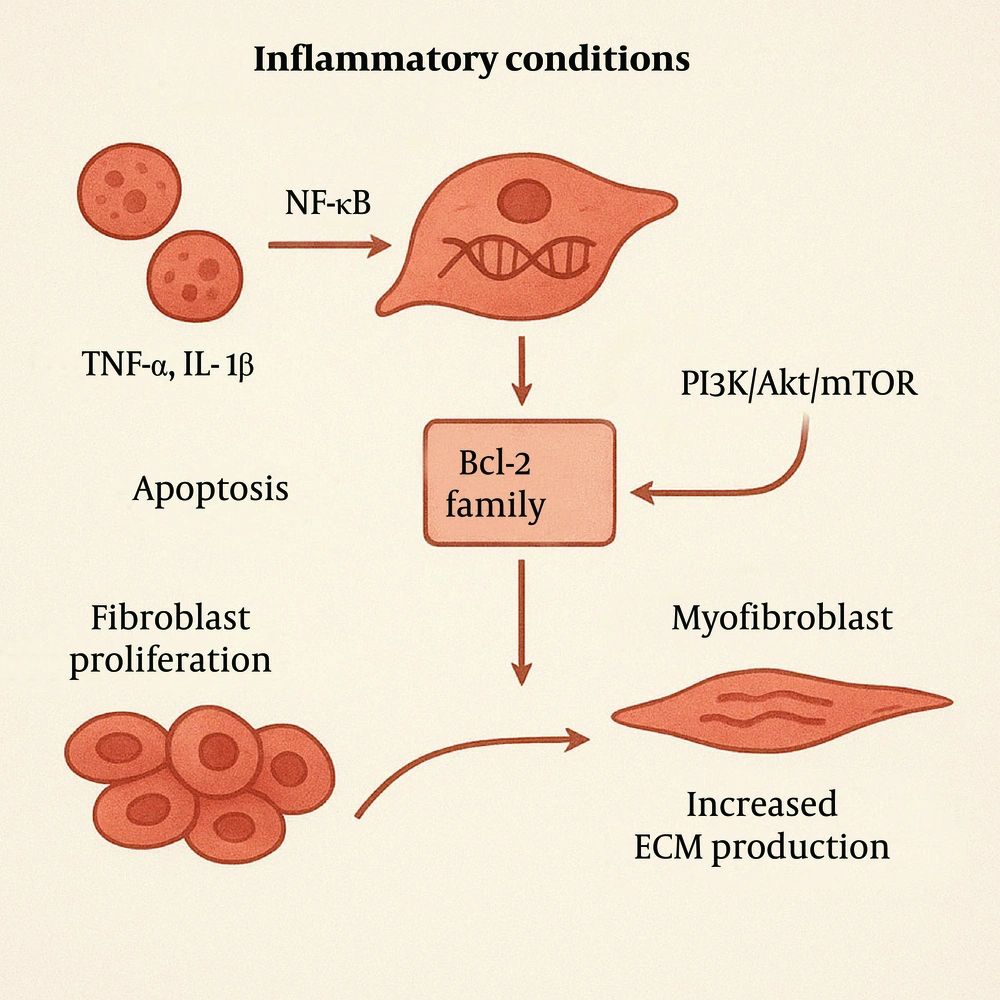

Under inflammatory conditions, elevated levels of certain inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, activate transcription factors like nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). This activation increases the expression of anti-apoptotic genes, such as members of the Bcl-2 family, enabling fibroblasts and myofibroblasts to resist apoptosis (9). Additionally, inflammatory mediators can activate signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, further promoting cell survival and inhibiting apoptosis. These mediators further promote fibroblast proliferation by activating cell cycle progression. These proliferating fibroblasts subsequently differentiate into myofibroblasts, which exhibit enhanced synthetic capacities to produce large quantities of ECM components, such as collagen and fibronectin (Figure 3).

Growth factors like TGF-β and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are upregulated in the inflammatory milieu, directly promoting fibroblast proliferation and activation (10). To counteract tissue damage, intestinal epithelial cells attempt to repair the affected areas through proliferation and migration. However, in the context of chronic inflammation, this repair process is often ineffective and may even exacerbate local tissue injury. When apoptosis decreases and proliferation increases, ECM produced by fibroblasts accumulates within the tissue, leading to the formation of fibrotic plaques (Figure 4) (11, 12).

Recent studies have highlighted the regulation of apoptosis and proliferation imbalance as a key therapeutic target for fibrosis. For instance, drugs targeting apoptotic pathways, such as Bcl-2 inhibitors, and therapies that suppress fibroblast activation are under active investigation (13).

2.4. Non-inflammatory Mechanisms of Fibrosis

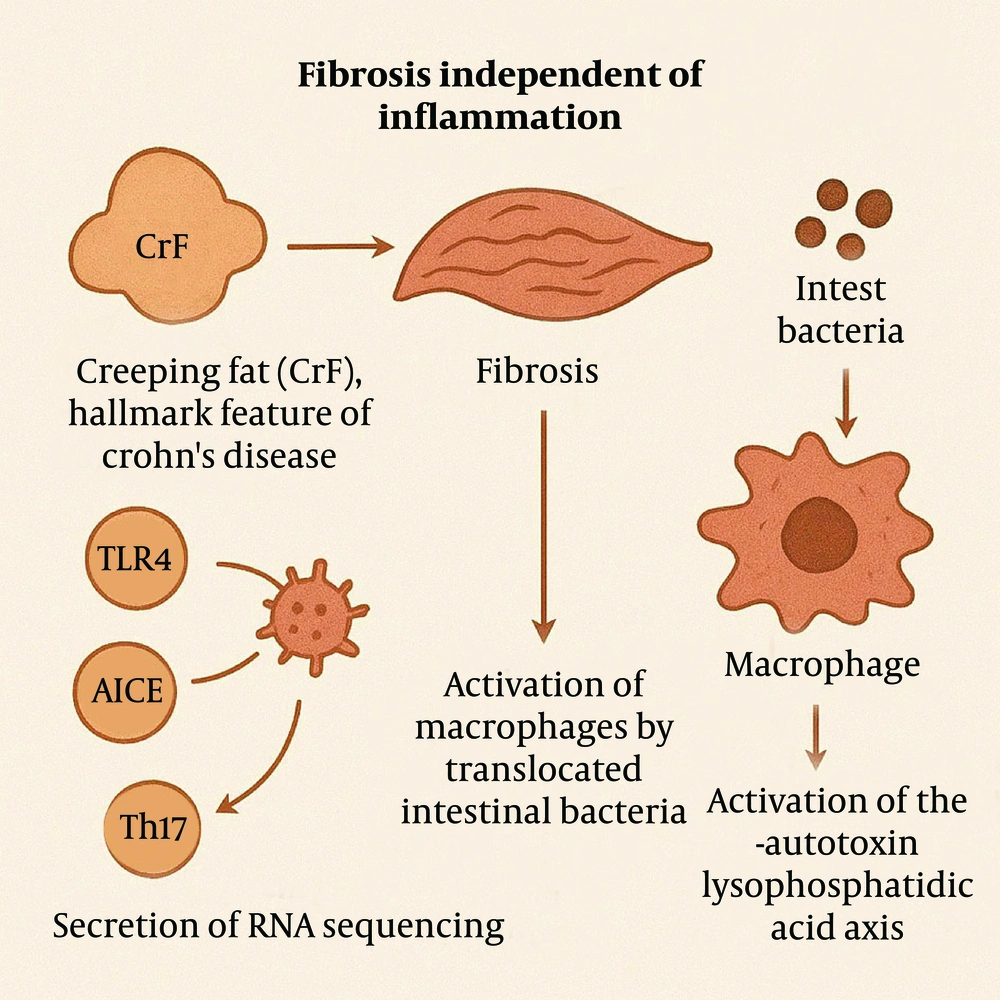

Although inflammation serves as a trigger for fibrosis, studies have shown that the progression of fibrosis can occur independently of the inflammatory process. Certain cellular or molecular factors have been implicated in fibrosis, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), Th17 immune responses, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (14-16). Additionally, creeping fat (CrF), a hallmark feature of CD, is considered to play a significant role in fibrosis development (17). Current research suggests that CrF formation is a response to local microbial translocation into the mesentery following intestinal barrier disruption (18-21).

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed the presence of both pro-fibrotic and pro-adipogenic signals within CrF. These signals may promote fibrosis through several mechanisms, including activation of macrophages by translocated intestinal bacteria (19), secretion of adipokines that facilitate macrophage transformation (18), activation of the autotoxin-lysophosphatidic acid axis (22), and secretion of free fatty acids (Figure 5) (23-25).

2.5. Mucosal Barrier and Microbiota

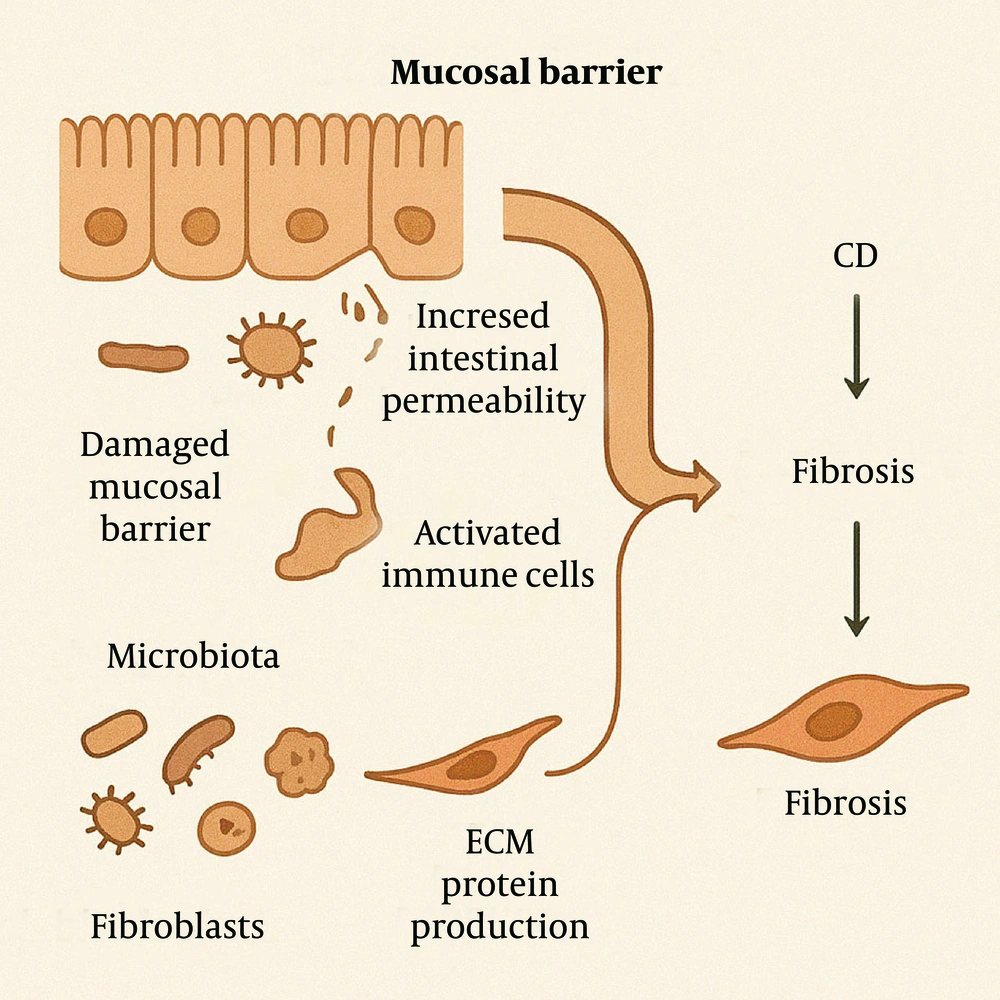

In CD, the disruption of the intestinal mucosal barrier leads to dysbiosis and the activation of stromal cells. Chronic alterations in the intestinal mucosal barrier and microbiota are critical in the pathogenesis of CD and its associated fibrosis. Damage to the mucosal barrier increases intestinal permeability, allowing bacteria and antigens to traverse the mucosa into the lamina propria. This triggers the activation of immune cells, thereby initiating or exacerbating inflammatory responses and promoting the progression of fibrosis (26).

The impairment of the mucosal barrier can manifest as structural and functional abnormalities in tight junction proteins, which disrupt epithelial cell connections and increase intestinal permeability. This heightened permeability may facilitate the progression from IBD to intestinal fibrosis (27). Furthermore, the gut microbiota plays a significant role in CD-related fibrosis. The composition and function of the microbiota can influence the host immune response and inflammatory state, thereby affecting the fibrotic process. For instance, certain bacterial components can activate intestinal fibroblasts and promote the production of ECM proteins, suggesting that specific microbiota-derived molecules may alter the transcriptional state of fibroblasts and contribute to intestinal fibrosis (Figure 6) (28).

2.6. Genetic Factors

Genetic factors play a crucial role in the development of intestinal fibrosis, involving not only specific genetic variants but also epigenetic modifications and interactions with the gut microbiota. These factors collectively influence the intestinal inflammatory response and repair processes, ultimately contributing to fibrosis progression. For example, mutations at certain loci in genes such as NOD2, ATG16L1, CX3CR1, IL-23R, and MMP3 have been associated with the fibrotic-obstructive phenotype of CD (29).

The NOD2 gene encodes an intracellular pattern recognition receptor that detects bacterial cell wall components, playing a role in the intestinal inflammatory response and fibrosis. Similarly, polymorphisms in the TLR4 gene, which regulates immune responses to bacterial stimuli, are linked to an increased risk of fibrotic strictures in CD (Figure 7) (30).

3. Diagnosis of Intestinal Fibrosis

Intestinal fibrosis in CD primarily manifests as intestinal strictures, which may result in varying degrees of obstruction symptoms. Currently, intestinal fibrosis can be assessed using various imaging modalities, including computed tomography enterography (CTE), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE), endoscopy, and ultrasound.

3.1. Computed Tomography Enterography

The CTE enables the evaluation of intestinal wall thickness, mucosal enhancement, bowel wall stratification, mesenteric vascularity, and the extent of lesions, thereby facilitating the assessment of intestinal strictures (31). However, mesenteric vascular proliferation is more strongly associated with tissue inflammation than with fibrosis. Since fibrosis and inflammation often coexist, CTE may not reliably differentiate between fibrotic and inflammatory strictures (32).

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Enterography

The MRE provides comparable capabilities to CTE for assessing intestinal strictures, but it is currently considered the most accurate modality for evaluating fibrosis (33). This is because gadolinium enhancement in fibrotic tissue exhibits delayed characteristics compared to its enhancement in inflammation-rich vascular tissues (34). Indicators such as T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) signal intensity, apparent diffusion coefficient values, intestinal motility, and time-dependent bowel wall enhancement may aid in distinguishing fibrosis within stenotic bowel segments (35). However, severe fibrotic strictures often coexist with active inflammation, and low signal intensity on T2WI cannot entirely predict the presence or absence of intestinal fibrosis. Advanced MRI techniques, including diffusion-weighted imaging, dynamic contrast enhancement, intravoxel incoherent motion imaging, and magnetization transfer imaging, offer promising non-invasive methods for quantifying the extent of intestinal fibrosis in CD (36, 37).

3.3. Ultrasonography

Conventional ultrasonography has limited utility in differentiating between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures. However, specialized imaging techniques can enhance this differentiation. In ultrasound imaging, CD-related fibrosis typically presents as hyperechoic changes in the submucosa, while hypoechoic bowel wall signals are associated with inflammatory edema and congestion. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) can evaluate the distribution of microvasculature within the bowel wall, aiding in the differentiation of fibrotic strictures (38).

Studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between the degree of histologically confirmed bowel fibrosis and bowel wall stiffness measured by ultrasound elastography (39). This suggests that ultrasound elastography can predict intestinal fibrosis. Real-time shear wave elastography offers the additional capability of estimating tissue stiffness, enabling more precise grading of fibrotic lesions (40). Ultrasonography also has the advantages of being user-friendly, highly reproducible, and suitable for dynamic monitoring of disease progression. However, its diagnostic accuracy is highly dependent on the operator's skill level.

3.4. Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows for direct visualization of intestinal strictures but has limited ability to determine the presence of fibrosis. It is also not particularly useful for diagnosing multifocal strictures (41). Typically, fibrotic strictures appear as narrowed segments without concomitant mucosal inflammation or ulceration. However, when both active inflammation and fibrotic strictures coexist, endoscopy can reveal mucosal inflammation or ulceration at the site of stricture (42).

It is important to note that no single diagnostic method is sufficient to comprehensively assess the extent of CD and intestinal fibrosis. Therefore, a combination of diagnostic techniques is commonly employed in clinical practice. For example, combining MRE and endoscopic ultrasound can provide detailed information on both full-thickness and localized bowel wall involvement. Additionally, combining imaging techniques with biomarker testing allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of disease activity and fibrosis at both macroscopic and microscopic levels.

Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in the diagnosis of CD is gaining increasing attention. By analyzing large volumes of imaging and endoscopic data using machine learning algorithms, AI systems can assist clinicians in more accurately identifying lesions, assessing disease severity, and predicting treatment responses. For instance, one study utilized deep learning algorithms to analyze MRE images, achieving better results than human interpretation in distinguishing between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures, with an accuracy rate of 89.7% (43). The comparison of various diagnostic techniques is shown in Table 2.

| Modalities | Fibrosis Detection | Limitations | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTE | ★★☆☆☆ (Low) | Tissue inflammation interfering | Not reliable for fibrosis |

| MRE | ★★★★☆ (High) | Cost; limited availability | Gold standard for fibrosis |

| CEUS | ★★★☆☆ (Moderate) | Operator-dependent | Real-time microvascular assessment |

| Endoscopy | ★★☆☆☆ (Low) | Limited ability to determine the presence of fibrosis | Reveal mucosal inflammation or ulceration |

| AI-assisted | ★★★★☆ (High) | Requires validation cohorts | Automated stricture classification |

Abbreviations: CTE, computed tomography enterography; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; CEUS, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography; AI, artificial intelligence.

4. Treatment of Intestinal Fibrosis

4.1. Pharmacological Treatment

Currently, there are no approved drugs that can prevent or reverse CD-related intestinal fibrosis. The primary treatment approach remains the active control of intestinal inflammation (44). Developing effective drugs to inhibit intestinal fibrosis is a major challenge in CD research. In other fibrotic conditions such as liver fibrosis and pulmonary fibrosis, several drugs have advanced to phase 2/3 clinical trials, including the Farnesoid X receptor agonist cilofexor, chemokine receptor inhibitor cenicriviroc, and the Janus kinase inhibitor selonsertib (45). However, research focused on inhibiting intestinal fibrosis is mostly still in the preclinical or animal model stage.

In chronic intestinal inflammation models, Lactobacillus helveticus strain producing Hsp65 antigen has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects. Mice treated with Hsp65 exhibited decreased levels of IL-13 and TGF-β, along with increased IL-10 concentrations, confirming the potential effectiveness of this novel anti-fibrotic strategy (28). In mice with fibrosis induced by TNBS or DSS, oral administration of betulinic acid hydroxamate ester was found to prevent colonic inflammation and fibrosis, significantly lowering both fibrosis and inflammation biomarkers. Additionally, the treated mice showed improved epithelial barrier integrity and wound healing, providing a theoretical foundation for further clinical studies (46). Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor AMA0825 has been shown to reverse intestinal fibrosis in rats and reduce the release of fibrotic factors in CD biopsy specimens (47). A PPARγ ligand with strong affinity, GED-0507-34, was shown to improve intestinal damage in DSS-treated mice and reduce the expression levels of Acta2, COL1a1, and Fn1. It also decreased fibrosis-specific markers, such as α-SMA and α2 type I collagen, displaying varying degrees of anti-fibrotic effects in animal models (48). These research advancements suggest that the development of anti-intestinal fibrosis drugs is progressing actively, with several drugs and therapeutic strategies being explored in hopes of finding effective methods to block or reverse intestinal fibrosis.

Moreover, gene therapy and stem cell therapy, as emerging treatment strategies, show potential applications in CD-related intestinal fibrosis. However, key issues such as ensuring accurate gene editing, stem cell origin, and safety need to be resolved before these therapies can be widely implemented.

4.2. Endoscopic and Surgical Treatment

When intestinal fibrosis worsens and leads to obstructive symptoms that are difficult to relieve or reappear shortly after temporary relief, endoscopic or surgical treatments should be considered. Endoscopic treatments primarily include endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD), endoscopic stent placement, and endoscopic stricturotomy (EST). The EBD is suitable for single, non-complicated strictures (not associated with fistulas, abscesses, atypical hyperplasia, or malignancy) that are less than 5 cm in length. The success rate and clinical efficacy exceed 80% (49).

Endoscopic stent placement involves the use of self-expanding metal stents or biodegradable stents. Some small studies have shown that biodegradable stents have a higher technical success rate and long-term symptom relief (50), while self-expanding metal stents have a technical success rate and obstruction relief rate of 93% and 60.9%, respectively (51). However, a follow-up study lasting over two years found that approximately 41.3% of patients who underwent stent placement required repeat endoscopic treatment or surgical intervention (52), and the relief time after stent placement was relatively short. Spontaneous stent migration or dislodgement is common, limiting its clinical use.

The EST is primarily suitable for strictures of the anal and distal colon less than 7 cm in length. Non-uniform, non-concentric strictures are more suitable for EST treatment, with a technical success rate of up to 100%. Only 15.3% of patients required additional stricture-related surgery within one year after EST (53).

For stenosis of CD, the main surgical procedures include bowel resection and stricturoplasty (54, 55). Bowel resection is suitable for patients undergoing their first bowel surgery and those at low risk for short bowel syndrome. Stricturoplasty is used for patients with multiple strictures, those who have undergone extensive bowel resections, or those with short bowel syndrome, particularly for duodenal or terminal ileal strictures, as it maximizes bowel preservation (56). The comparison of treatment strategies for CD-related intestinal fibrosis is shown in Table 3.

| Treatment Strategies | Mechanism/Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-fibrotic drug development (experimental) | Targeting fibrosis pathways (e.g., FXR agonists, CCR inhibitors, JAK inhibitors); mostly in preclinical/early trials | Inspired by success in liver/lung fibrosis; multiple candidate drugs being tested | No approved drugs for intestinal fibrosis; efficacy/safety in humans unclear |

| Probiotics (e.g., Lactobacillus helveticus producing Hsp65) | Anti-inflammatory, IL-13 and TGF-β reduction, increase of IL-10 | Non-invasive, microbiota-targeted; showed anti-fibrotic effects in animal models | Limited to animal data; clinical efficacy unproven |

| Natural compounds (betulinic acid derivative) | Colonic inflammation and fibrosis reduction; epithelial barrier repair enhancement | Dual anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects; animal evidence supportive | No clinical trial data yet |

| ROCK inhibitor (AMA0825) | Intestinal fibrosis reversion; fibrotic factor release reduction | Effective in animal and biopsy studies; potential for reversal, not just prevention | Still experimental; long-term safety unknown |

| PPARγ ligand (GED-0507-34) | Decrease of fibrosis markers (α-SMA, collagen I) and intestinal damage improvement | Demonstrated strong anti-fibrotic effects in preclinical models | No human trials yet |

| Gene therapy | Targeting the modification of fibrosis/inflammation-related genes | Potentially precise and long-lasting | Technical, ethical, and safety challenges |

| Stem cell therapy | Repair promotion and modulating immune response | Potential regenerative effect | Safety, source, and standardization issues unresolved |

| EBD | Mechanical dilation of stricture (< 5 cm, non-complicated) | Success rate > 80%; minimally invasive; repeatable | Risk of recurrence; not suitable for long/multiple strictures |

| Endoscopic stent placement | Self-expanding or biodegradable stents | Provides temporary obstruction relief; biodegradable stents show longer effect | Stent migration common; ~41% need repeat/surgery within 2 y |

| EST | Incision of stricture (< 7 cm, distal colon/anal) | Technical success rate up to 100%; low surgery rate within 1 y (15.3%) | Limited to certain stricture types/locations |

| Surgery; bowel resection | Removal of fibrotic bowel segment | Effective for first surgery, low short bowel risk | Risk of recurrence; may lead to short bowel if repeated |

| Surgery; stricturoplasty | Widening of strictures without resection | Preserves bowel length; useful in multiple strictures or prior resections | Technically demanding; not suitable for all stricture sites |

Abbreviations: TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; EBD, endoscopic balloon dilation; EST, endoscopic stricturotomy.

5. Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Prevention and Treatment of Intestinal Fibrosis

5.1. Traditional Chinese Medicine's Understanding of Intestinal Fibrosis

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), there is no specific term for intestinal fibrosis. However, based on the symptoms caused by intestinal fibrosis, such as intestinal narrowing, it can be classified under categories like "accumulation" and manifests clinically as abdominal masses, with pain or distension. The blockage of the intestines and meridians by external pathogens results in the stagnation of Qi, leading to pain when blocked. When Qi stagnation impedes the circulation of blood, it causes blood stasis, depriving the intestines of nourishment, which may lead to ulcers. As blood stagnation worsens over time, accumulation gradually forms.

During the recurrent and chronic phases of the disease, various external pathogens interact with the Qi and blood in the intestines, exacerbating the stasis, making it difficult to resolve. This leads to the stagnation of blood, preventing new blood from being generated. This is the pathological foundation for the development of Qi stagnation and blood stasis in CD. The stagnation of Qi and the accumulation of blood not only exacerbate the condition but also interact with each other, accelerating the accumulation. The transition from deficiency to excess, and from excess to deficiency, runs through the chronic inflammation-to-fibrosis transformation process. Factors such as Qi stagnation, blood stasis, phlegm dampness, and abdominal masses are key pathological contributors to fibrosis. Therefore, eliminating these factors is the primary approach in TCM treatment for fibrosis-related diseases (57-59).

5.2. Research Progress in the Prevention and Treatment of Intestinal Fibrosis with Traditional Chinese Medicine

The TCM has shown some success in the prevention and treatment of fibrosis in organs such as the liver, lungs, and kidneys. For instance, compound medicines like Fufang Biejiaruangan Pian, Fuzheng Huayu Pian, and Anluo Huaxian Wan have been demonstrated to exert anti-fibrotic effects through mechanisms such as regulating immune responses, antioxidant properties, and inhibiting the activation of hepatic stellate cells (60).

Some flavonoid-based Chinese herbal monomers, such as hesperidin, hydroxy-safflor yellow A, dendrotoxin, rhodiola rosea glycosides, and ginsenosides, exhibit anti-fibrotic effects in liver and kidney tissues by acting through antioxidant mechanisms and inhibiting TGF-β1 and connective tissue growth factors (61-65).

However, research on the use of TCM for the prevention and treatment of intestinal fibrosis is still in its early stages. Scholars like Zhang Huixiang (66) have observed the effects of total flavonoids from Hibiscus mutabilis flowers on the synthesis of type I collagen by intestinal fibroblasts in rats. They found that total flavonoids from H. mutabilis could inhibit the generation of type I collagen by activating the AMPK/mTOR pathway to regulate autophagy, thereby improving intestinal fibrosis. However, this study lacked translational validation in human tissues.

Xu Su (67) used a modified Sanleng Wan to treat CD-related intestinal fibrosis and found that this TCM formula could improve clinical outcomes of CD-related intestinal stenosis. But the clinical trials had a small sample size (n = 36) and short follow-up (3 months), limiting statistical power. Further rat experiments demonstrated that Sanleng Wan promoted the production of PPARγ and reduced the levels of intestinal fibrosis-related factors, thereby exerting anti-fibrotic effects (68).

Network pharmacology approaches revealed that Qingchang Tongluo Decoction inhibited the TGF-β1/Smad/VEGF pathway and reduced fibrosis markers in TNBS-induced rats, but this research lacked purified active compounds and long-term safety and human data (69). Xue-Jie-San (XJS) as a single formula showed potential to prevent intestinal fibrosis by blocking Notch 1 and FGL 1 signaling pathways (70). Yet mechanistic studies predominantly rely on DSS/TNBS-induced murine models, which may not fully recapitulate human CD pathophysiology. The comparison of these studies is shown in Table 4.

| Medicine/Formula | Target/Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fufang Biejiaruangan Pian, Fuzheng Huayu Pian, Anluo Huaxian Wan | Regulating immune response, antioxidant, inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation | Proven anti-fibrotic effects in liver/lung/kidney; multi-target | Evidence mainly from non-intestinal fibrosis; limited CD-specific data |

| Flavonoids (hesperidin, hydroxy-safflor yellow A, dendrotoxin, rhodiola glycosides, ginsenosides) | Antioxidant effects, inhibition of TGF-β1 and connective tissue growth factors | Clear molecular targets; testing in liver/kidney | Lack of intestinal fibrosis-specific evidence |

| Total flavonoids of Hibiscus mutabilis | Activating AMPK/mTOR pathway, regulating autophagy, inhibition collagen I synthesis | Showing inhibition of intestinal fibroblast collagen production | No human tissue validation; only rat fibroblast data |

| Modified Sanleng Wan | Promoting PPARγ, fibrosis-related factors reduction | Clinical trial in CD patients (n = 36) showing benefit; supported by animal studies | Small sample size, short follow-up (3 months); limited statistical power |

| Qingchang Tongluo decoction | Inhibition of TGF-β1/Smad/VEGF pathway, fibrosis markers reduction | Network pharmacology + animal data; multi-target regulation | Active compounds not purified; lack of long-term safety and human studies |

| XJS | Blocking Notch1 and FGL1 signaling | Showing fibrosis prevention in animal models | Evidence only from DSS/TNBS-induced mice; need of human validation |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn's disease; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; XJS, Xue-Jie-San.

These studies suggest that TCM compound formulas or single components may serve as potential treatments for intestinal fibrosis. However, translating experimental results into clinical applications still requires further exploration. Future TCM research should prioritize randomized controlled trials (RCTs), standardized fibrosis biomarkers, and multi-center validation to mitigate selection bias.

6. Summary and Outlook

Intestinal fibrosis in CD remains a significant challenge in the diagnosis and treatment of the condition. In recent years, research on the diagnosis and treatment of CD has gained significant momentum. With the advancement of multi-omics, gut microbiota, cytokines, and other related fields of study, the mechanisms underlying the occurrence and development of intestinal fibrosis have gradually been revealed. However, effective prevention and reversal of intestinal fibrosis remain to be fully explored.

Clinically, a combined approach integrating both TCM and Western medicine may provide an effective solution to the challenge of CD-related intestinal fibrosis. By combining the strengths of both medical systems, such an approach could help control inflammatory activity while preventing or alleviating the progression of fibrosis, thus achieving a comprehensive treatment strategy that addresses both the symptoms and root causes of the disease.

Future research on integrated treatment strategies should focus on deepening our understanding of the disease mechanisms, developing more precise diagnostic and treatment methods, and exploring the molecular and cellular mechanisms of TCM. Additionally, large-scale, long-term clinical studies are needed to further validate the effectiveness and safety of such approaches.