1. Context

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system (CNS), defined by immune-mediated demyelination and progressive neurodegeneration (1). The exact etiology of MS remains incompletely characterized, though interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and immune system dysfunction are considered contributory (2, 3). The immune system attacks myelin, leading to inflammation and damage, which in turn causes neurological symptoms and nerve apoptosis (4). The implementation of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) in MS treatment has been linked to the emergence of secondary autoimmune diseases (SADs), representing an unexpected therapeutic complication (5). However, as the utilization of these immunotherapies expands, there is an increasing awareness of potential adverse effects (6). Contemporary research has offered post-marketing insights, examining novel adverse effects of oral MS therapies, highlighting the importance of comprehensive understanding regarding treatment consequences (7, 8). This demonstrates the disease’s intricacy and the need for continued research to better understand its etiology and develop effective treatment plans. The development of secondary autoimmune dermatological conditions in patients receiving MS immunotherapy represents an additional complication of concern (9). Immunotherapy medications employed in MS treatment, including alemtuzumab, may result in secondary autoimmune manifestations (10). However, there is potential for the use of skin-induced immune tolerance, particularly through the use of dermal dendritic cells, in the treatment of MS (11). Recent studies further emphasize immune response modifications in MS patients, which may contextualize these dermatological risks (12). Additionally, associated conditions like spasticity treatments (13) and sleep disorders (14) highlight the multifaceted nature of MS complications.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to analyze existing literature to provide a comprehensive review of the current knowledge on the underlying mechanisms and risk factors associated with this complex interplay.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Data Sources

The present review focuses on identifying and analyzing autoimmune dermatological disorders associated with DMTs used to manage MS. A comprehensive search was conducted across three major databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus, for publications available up to January 2024.

3.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in three major databases — Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus — for publications available up to January 2024. The search terms included combinations of “multiple sclerosis” with (“Natalizumab” OR “Ocrelizumab” OR “Rituximab” OR “Alemtuzumab” OR “Ofatumumab” OR “Ublituximab”) and “case report”. Relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were also incorporated. The biologic agents of interest were selected based on treatment recommendations outlined in Wolters Kluwer’s UpToDate®. No additional filters for date (beyond up to January 2024) or study type were applied, but limits included English language and full-text availability only.

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (A) case reports or case series; (B) reports describing autoimmune dermatological complications associated with MS immunotherapy; and (C) availability of the full text in English. Exclusion criteria included (A) non-English publications; or (B) SADs other than dermatological disorders; (C) reviews, meta-analyses, letters to editors, clinical trials, and qualitative studies; (D) studies without patient timelines or outcomes; (E) non-biological MS therapies; and (F) incomplete case descriptions. To standardize the scope, autoimmune conditions were identified using the 2024 Autoimmune Disease List of the Global Autoimmune Institute.

3.4. Data Extraction

Data from the eligible studies were screened and extracted using EndNote® version 7 (Clarivate Analytics). Two independent researchers reviewed the data to ensure accuracy and consistency, with the findings subsequently cross-verified by two additional team members.

3.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included case reports was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist (15). This tool assesses eight Likert key aspects such as patient demographics, clinical history, diagnostic approaches, therapeutic interventions, and post-treatment outcomes of case reports. Each case report was systematically reviewed to determine its methodological robustness. The assessment also included an evaluation of the overall utility of the case reports, as detailed in Table 1.

| Authors | References No. | Were Patients’ Demographic Characteristics Clearly Described? | Was the Patient’s History Clearly Described and Presented as a Timeline? | Was the Current Clinical Condition of the Patient on Presentation Clearly Described? | Were Diagnostic Tests or Assessment Methods and the Results Clearly Described? | Was the Intervention(s) or Treatment Procedure(s) Clearly Described? | Was the Post-intervention Clinical Condition Clearly Described? | Were Adverse Events (Harms) or Unanticipated Events Identified and Described? | Does the Case Report Provide Takeaway Lessons? | Overall Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molazadeh et al., 2021 | (16) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Tzanetakos et al., 2022 | (17) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Jakob Brecl et al., 2022 | (18) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Dikeoulia et al., 2021 | (19) | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Include |

| Darwin et al., 2018 | (20) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Include |

| Zimmermann et al., 2017 | (21) | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Borriello et al., 2021 | (22) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Alcala et al., 2019 | (23) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | UC | Y | Y | Include |

| Naranjo Guerrero et al., 2023 | (24) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Chan et al., 2019 | (25) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Ruck et al., 2018 | (26) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | UC | Include |

| Bolton et al., 2020 | (27) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Include |

| Millan-Pascual et al., 2012 | (28) | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Vacchiano et al., 2018 | (29) | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Lappi et al., 2022 | (30) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Include |

| Tsourdi et al., 2015 | (31) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | UC | Y | Include |

| Leussink et al., 2018 | (32) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | Y | Y | Include |

| Durcan et al., 2019 | (33) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Include |

| Bohm et al., 2021 | (34) | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Include |

4. Results

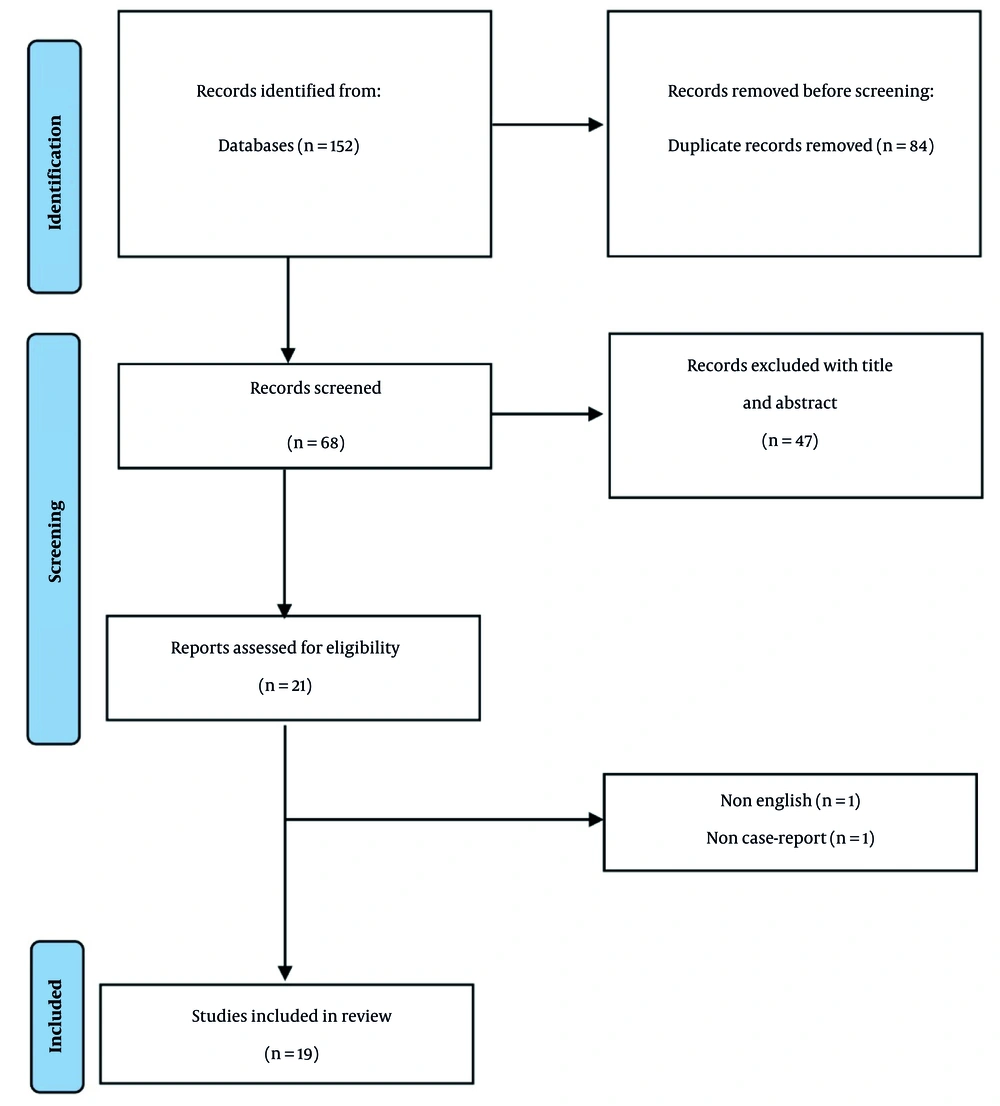

A comprehensive systematic search of the specified databases through January 17, 2024, identified 152 articles. Following the removal of 84 duplicate entries, 68 articles remained for independent evaluation by two researchers. Title and abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of 47 articles. Subsequent full-text review of the remaining studies led to the elimination of two additional articles based on language restrictions and study design criteria (Figure 1). Finally, 19 articles met eligibility requirements, documenting 26 patients’ clinical details. These reports originated primarily from Germany, Spain, and Italy, with additional cases from Canada, Greece, Ireland, the UK, Iran, the USA, and Croatia. The included studies are summarized in Table 2. Ten studies examined autoimmune dermatologic complications of alemtuzumab in MS patients, while natalizumab and ocrelizumab were each the subject of 4 studies, with the remainder documenting rituximab-related effects. In total, 26 patients from 19 studies involving 4 distinct injectable biological MS therapies were identified.

| Drugs and Study | Type of Autoimmunity | Medical History | Timeline of Occurrence | Treatment | Outcome/MS Treatment | Demographic Characteristics | Year of Occurrence/Country | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alemtuzumab | ||||||||

| Ruck et al., 2018 (26) | Vitiligo | MS since 2004 | 52 months after initiation, 10 months after 2nd infusion | NM | NM | A 31 year-old woman | 2016/Germany | RRMS |

| Ruck et al., 2018 (26) | Vitiligo | MS Since 2001, fingolimod | 18 months after initiation (6 month after the 2nd dose) | NM | NM | A 34 year-old A man | 2017/Germany | MS |

| Ruck et al., 2018 (26) | Vitiligo | MS since 2015, fingolimod | 14 months after initiation (2 month after the 2nd dose) | NM | NM | A 42 year-old woman | 2018/Germany | MS |

| Bohm et al., 2021 (34) | Halo naevus-like hypopigmentation | MS since 2016 | 11 months after 2nd infusion | NM | NM | A 33 year-old male | 2018/Germany | Highly reactive RRMS |

| Alcala et al., 2019 (23) | Alopecia areata | MS since 4 years ago /fingolimod | 9 months after the 2nd cycle | Interlesional steroids | Improved but new plaques occured again/NM | A 28 year-old woman | 2017/Spain | Aggressive RRMS |

| Dikeoulia et al., 2021 (19) | Alopecia areata | MS since 2006 | 18 months after 2nd infusion | Topical clobetasole then topical immunotherapy | NM | A 31 year-old woman | 2019/ Germany | RRMS |

| Tsourdi et al., 2015 (31) | Alopecia areata with hyperthyroidism | MS since 2004, smoker | 34 months after infusion | Topical mometasone but not effective | Thyroidectomy/NM | A 34 year old women | 2012/Germany | MS |

| Chan et al., 2019 (25) | Alopecia areata | MS since 2015 | 2 months after 2nd course | Interlesional triamcinolone then IV methylprednisolone | Improved and regrowth/NM | A 31 year-old woman | 2017/Canada | RRMS |

| Alcala et al., 2019 (23) | Alopecia universalis | MS since 2005; With history of vitiligo | 5 months after 2nd cycle | Not stated | His vitiligo too was worsened/NM | A 27 year-old man | 2017/Spain | Aggressive RRMS |

| Borriello et al., 2021 (22) | Alopecia universalis with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | NM | 12 months after 2nd dose | Topical minoxidil and retinoic acid/low vid levels | No improvement/NM | A 32 year-old woman | 2019/Italy | MS |

| Borriello et al., 2021 (22) | Alopecia universalis with swelling in her hand | MS since 2015 | 12 months after 2nd dose | IV steroids+pimecrolimus+betamethasone | No hair growth/NM | A 36 year-old woman | 2018/Italy | MS |

| Leussink et al., 2018 (32) | Alopecia universalis | MS since 2014 | 6 months after the last infusion | No intervention | Regrowth after 9 months/NM | A 29 year-old woman | 2015/Germany | Highly active RRMS |

| Tzanetakos et al., 2022 (17) | Alopecia universalis with transient accommodation spasm | MS since 2005 | Fingolimod/8 months after initiation | IV and oral steroid | Roughly one year after Partial hair regrowth/continued | A 24 year-old man | 2018/Greece | MS |

| Zimmermann et al., 2017 (21) | Alopecia universalis | NM; Had received mitoxantrone before | 6 months after 2nd cycles | WHO-UMC probable/likely/not consented to any therapy | No improvement /NM | A 49 year-old man | NM/Germany | RRMS |

| Natalizumab | ||||||||

| Durcan et al., 2019 (33) | Cutaneous sarcoidosis-like reaction | MS since 2017 | Following 4th dose | Topical steroids | Poorly responsive/after 8 weeks subsided/discontinued | A 41 year-old woman | 2019/Ireland | MS |

| Bolton et al., 2020 (27) | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus with positive anti rho ab | NM | Following 2nd infusion | Oral and topical steroid then to MMF | Rash improved/NM | A 51 year-old man | NM/UK | MS |

| Millan-Pascual et al., 2012 (28) | Psoriasis (reactivation) | NM; Topical agents + MTX | After 6th infusion | UVB + topical | Slight resolution/continued | A 31 year-old woman | NM/Spain | RRMS |

| Vacchiano et al., 2018 (29) | Arthritic psoriasis | 20 years history of MS; Positive family history for psoriasis | Skin lesions, after 19th infusion and a month later, arthritis | Steroid | Partially effective/changed to DMF | A 56 year-old woman | NM/Italy | RRMS |

| Ocrelizumab | ||||||||

| Lappi et al., 2022 (30) | Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis | NM | 3 months after the last dose | Treatment with UVB and calcipotriol/betamethasone | Complete resolution/NM | A 38 year-old woman | NM/Italy | Highly active MS |

| Darwin et al., 2018 (20) | Psioriasiform dermatatis | MS diagnosed at 45/trigeminal neurolgia | 3.5 months after 2st infusion (end of induction) | 5 on Naranjo Scale/terbinafine then clobetazole | Improvement /continued | A 68 year-old woman | 2018/USA | MS |

| Naranjo Guerrero et al., 2023 (24) | Psioriasiform dermatatis/ fingernails was involved | NM | 11 months after 2nd dose | Clobetazole/partially responsive | NM/not discontinued | A 33 year-old man | NM/Spain | RRMS |

| Naranjo Guerrero et al., 2023 (24) | Psioriasiform dermatatis | NM | 4 months after 1st dose | Clobetazole topical/complete response | NM/not discontinued | A 36 year-old woman | NM/Spain | RRMS |

| Naranjo Guerrero et al., 2023 (24) | Psioriasiform dermatatis | NM | 5 months after 1st dose | Calcipo/betamethasone | NM/not discontinued | A 45 year-old woman | NM/Spain | RRMS |

| Jakob Brecl et al., 2022 (18) | Psoriasis | MS since 2020 | 6 months after 1st cycle | NA oral and topical | Moderate improvement/discontinued | A 40 year-old woman | 2021/Croatia | PPMS |

| Jakob Brecl et al., 2022 (18) | Psoriasis | MS since 2019; HTN and asthma | 1 month after 2nd cycle | NA topical | Partially regressed/discontinued | A 66 year-old woman | 2020/Croatia | PPMS |

| Rituximab | ||||||||

| Molazadeh et al., 2021 (16) | Psoriasis | MS since 2005 with migraine, bipolar disorder, seizure | 2 months after 4th cycle | Topical steroids | Improved/continued | A 39 year- woman | 2020/Iran | MS |

Abbreviations: MS, multiple sclerosis; RRMS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive multiple sclerosis.

4.1. Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab represents a monoclonal antibody that targets CD52 and has demonstrated efficacy as a therapeutic option for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other lymphoid malignancies (35). Studies have shown its effectiveness in diminishing relapse frequency and decelerating disability progression in MS, as well as demonstrating positive effects on radiological parameters (36). However, its clinical use correlates with the emergence of acquired autoimmune conditions, particularly thyroid-associated disorders, requiring vigilant monitoring and clinical management (37).

4.1.1. Autoimmune Complications

The autoimmune adverse reactions most frequently linked with alemtuzumab encompass thyroid disorders, manifesting in 20 - 30% of cases, with Graves’ disease being the predominant clinical presentation (38). Immune thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, hepatitis, encephalitis, myasthenia gravis, Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, alopecia, myositis, and type 1 diabetes are additional autoimmune sequelae of this therapeutic agent (39). The emergence of these complications appears to correlate with the drug’s mechanism of action, which induces sustained lymphopenia and subsequent lymphocyte repertoire reconstitution (10).

4.2. Natalizumab

Natalizumab functions as a monoclonal antibody utilized in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) management (40). It selectively binds to the α4 subunit of α4β1 and α4β7 integrin receptors, thereby inhibiting α4-mediated leukocyte attachment to their corresponding counter-receptors (41). This mechanism prevents T-cell lymphocyte migration into the CNS, thereby reducing inflammation and neurological damage characteristic of MS.

4.2.1. Autoimmune Complications

Autoimmune hepatitis (42, 43), immune thrombocytopenic purpura (44), and rheumatoid arthritis (45) have been documented with natalizumab therapy. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include a transition toward Th17-mediated inflammatory responses while concurrently blocking Th1 cell entry (45); however, further investigation is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and identify potential risk factors for these adverse effects.

4.3. Ocrelizumab

Ocrelizumab represents a humanized, second-generation, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that has been used in RRMS and early primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). Through binding to CD20 protein expressed on B-cells, it achieves B-cell depletion, thus preventing attacks on the CNS (46).

4.3.1. Autoimmune Complications

Ocrelizumab therapy has been correlated with an elevated risk for psoriasis development and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (47). Furthermore, glomerulosclerosis and Graves’ disease cases have been documented (48, 49). The precise mechanism remains unclear, though some hypotheses suggest a potential association with immune system dysregulation via B-cell depletion (50).

4.4. Rituximab

Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody that targets CD20-expressing B-cells, has been utilized in RRMS treatment (51). In comparison to rituximab, ocrelizumab binds to a distinct but overlapping CD20 epitope (52).

4.4.1. Autoimmune Complications

Several reports document rituximab-induced psoriasis (16) and ulcerative colitis (53) in MS patients. The proposed mechanism involves elimination of B-cell regulatory function that normally controls excessive T-cell activation (16).

5. Discussion

This systematic review of case reports constitutes the initial comprehensive evaluation of case reports examining secondary autoimmune dermatological disorders precipitated by biological immunotherapy agents utilized in MS treatment. We systematically analyzed 19 articles meeting inclusion criteria, encompassing 2 studies from the Americas, 16 from Europe, and 1 from Asia. Among these, ten studies examined alemtuzumab, which correlated with autoimmune dermatological complications in 14 patients. Four studies documented natalizumab, with 4 patients experiencing dermatological adverse reactions, while four additional studies addressed ocrelizumab-related dermal complications, affecting 7 patients. One case study described a single patient who developed secondary autoimmune dermatological disorders associated with rituximab. In total, 26 patients were identified with autoimmune dermatologic adverse effects. Notably, we found no studies documenting autoimmune dermatological complications with ofatumumab or ublituximab, two recently approved monoclonal antibodies for MS treatment, with the majority of complications attributed to alemtuzumab. Various autoimmune mechanisms have been proposed by the reviewed case reports, which are outlined in Table 3.

| Agents and Disorders | Findings and Proposed Pathogenesis |

|---|---|

| Alemtuzumab | |

| Vitiligo and halo naevus-like hypopigmentation | Melanocytes destruction of not-depleted melanocyte-specific CD8+ T-cells (34); Rise in interleukin-21 which drives proliferation of chronically activated, oligoclonal, effector memory T-cells (26); Increment in anti-tyrosinase antibodies and sharp rise in antibodies against tyrosinase -related protein 1 (34) |

| Alopecia areata and Alopecia universalis | Profound immunosuppression followed by immune cell reconstitution leads to an increased number of T and B lymphocytes and anti-inflammatory cytokines leading to auto reactivity and reduced self-tolerance (23); The unregulated expansion of the B-cell pool, and increase levels of B-cell activating factor leading to uncontrolled autoantibody production (22); Escaped peripheral T-cells proliferate to restore the T repertoire plus over-expression of cytokines, reduced thymic output, and the Treg/non-Treg ratio skewing (22); Immune reconstitution after immunosuppression of alemtuzumab, during which B-cells recover more rapidly than T-cells, resulting in insufficient T-cell regulation, leading to uncontrolled B-cell autoreactivity (19); Lower vitamin D levels leading to rise in interleukin-21 and -17 inducing Th17 and inhibit re-differentiation of regulatory T-cell (22) |

| Natalizumab | |

| Cutaneous sarcoidosis-like reaction | Altering expression of the α4β1− integrin, surrounding lymphocytes and macrophages of sarcoid granulomas which changes the structural extracellular matrix, inducing an inflammatory cascade and subsequent formation of granulomata (33) |

| Cutaneous lupus erythematosus | Apoptosis elevated rates are with α4β1-integrin interactions’ interference, leading to presentation of autoantigens and formation of autoantibodies (27); Disrupted signaling of α4β1-integrin important to T-cell progenitors’ thymic selection (27); Suppressed α4β1-integrin activation related to decrease in the differentiation and suppressive function of peripheral T regulatory cells (27) |

| Psoriasis | In chronic inflammation, proinflammatory cytokines’ dysregulated production leads to adhesion molecules expression rise, blockade of one of these molecules can be compensated for by other pathways (28) |

| Arthritic psoriasis | Altering laminin function (29) |

| Ocrelizumab | |

| Psioriasiform dermatatis | Depletion of regulatory B‐lymphocytes with immunomodulatory function through interleukin‐10 and proinflammatory cytokines release such as tumor necrosis factor‐α, interleukin-6 and -8 (24) |

| Psoriasis | B-cell depletion stops the B-cells regulatory effect on T-cells population (30); Preceding the release of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8, promoting angiogenesis, generating a pro-inflammatory environment, inducing keratinocyte proliferation, and attracting neutrophils (30); Increment the susceptibility to bacterial infection and modification of the microbiome (30) |

| Rituximab | |

| Psoriasis | Removal of B-cell regulatory function by controlling excessive T-cell activity (16); Induce complement activation (16) |

Several patients have been documented with psoriasis development during interferon beta (IFNB) therapy, with some cases showing plaque formation at injection sites. This has been theorized to involve stimulation of the interleukin-23-Th17 pathway, associated with psoriasis pathogenesis, activating granulocyte recruitment and proinflammatory factor release in dermal tissue (28). Interleukin-17 is recognized for inhibiting keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation while simultaneously promoting Th17 cell recruitment, which produces additional interleukin-17, creating a positive feedback loop associated with psoriatic inflammatory responses (29). Documentation of new arthritis during IFNB treatment was also published in 2010 (29). One patient developed alopecia following alemtuzumab during the 4 - 5 year follow-up of 61 patients with high disease activity MS (21). Two individuals in another observational study of 100 patients followed for 6.2 years experienced alopecia characterized as an autoimmune complication after alemtuzumab treatment (54). The pathophysiological basis of alemtuzumab-induced autoimmunity remains inadequately understood. Given the high prevalence of antibody-mediated autoimmune complications, B-cells are presumed to be primary mediators (26). Additionally, chronic activation and proliferation of oligoclonal, effector memory CD8+ T-cells represents one hypothesis explaining this phenomenon (34). Another study proposed that following initial lymphopenia induction (1) The subsequent expansion of T-cells reactive to self-antigens that escaped depletion, combined with increased likelihood of self-antigen encounter and/or; (2) The subsequent B-cell increase are responsible for autoimmune disease secondary to alemtuzumab use (25). Furthermore, analysis demonstrated an increased secondary autoimmunity risk in patients treated with alemtuzumab who previously received fingolimod (17).

Natalizumab specifically targets the α4 integrin subunit, present on both α4β7 and α4β1, also known as very-late antigen-4 (VLA-4). While leukocyte endothelial adherence represents the primary integrin function, α4-integrins also contribute to tissue-specific lymphocyte trafficking in both physiological and pathological contexts. Their blockade has demonstrated paradoxical exacerbation in animal IBD models. The VLA-4 may be crucial for lymphocyte CNS trafficking. In inflammatory conditions like MS, the VLA-4 ligand, VCAM-1, is substantially increased in CNS microvessels (28). Similar to natalizumab, vedolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting α4β7 integrin, was associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) during treatment (27). Efalizumab, targeting the integrin αL subunit, has been implicated in autoimmune disorder development such as lupus-like syndrome (28).

Psoriasiform dermatitis induced by anti-CD20 therapy has been documented in literature, primarily associated with the chimeric monoclonal antibody, rituximab (24). A descriptive study conducted in the United States indicated that psoriasiform dermatitis incidence linked to B-lymphocyte-depleting MS treatments was significantly higher than that associated with other pharmaceutical therapies for this condition (55). Complement activation is less pronounced with ocrelizumab compared to rituximab, which may explain why psoriasis has been documented so infrequently with this medication (30). Understanding the specific mechanisms by which these drugs may trigger SADs is crucial for devising strategies to mitigate these complications and optimize patient care.

5.1. Conclusions

Multiple sclerosis represents one of the most challenging conditions to manage clinically. While novel interventions continue to emerge for symptom control, safety profiles — including dermatological SADs — remain critical, as evidenced by comparisons with other MS-related research on immune modifications and comorbidities. As additional novel medical interventions are commercialized to control its symptoms and complications, more safety reports are published. Secondary dermatological autoimmune disorders constitute some of the many documented adverse effects. A comprehensive review article addressing these novel side effects was lacking. We attempted to review reports on this issue to explain new aspects and help physicians better understand the problems their patients might encounter.

5.2. Limitations

Due to their high risk of bias, case reports and case series are often considered weak evidence sources. Additionally, language restrictions prevented us from reviewing some articles.