1. Background

Intracranial aneurysms, with a prevalence of 0.4 - 3.0% (1, 2), pose a significant health risk, particularly when rupture leads to subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with high morbidity and mortality (2, 3). Advances in non-invasive imaging, such as magnetic resonance angiography, have improved early detection, and preventive treatment is generally recommended for aneurysms measuring ≥ 7 mm (1, 4). Microsurgical clipping and endovascular coil embolization are the primary treatment modalities (5). While coil embolization is preferred due to its minimally invasive nature (6, 7), wide-necked and larger aneurysms remain challenging, with recurrence and retreatment rates of approximately 12% and 6%, respectively (8, 9). Larger aneurysms (≥ 7 mm) are more prone to recurrence due to coil compaction (10).

The use of flow diverters (FDs) has emerged as an alternative approach, offering improved conformability and metal coverage compared to conventional stents. However, despite growing use and favorable long-term results, FD treatment is not without risks. Reported complications include in-stent thrombosis, delayed rupture, hemorrhage, and ischemic events. While these risks have been examined in clinical trials, real-world data on complication rates, especially from diverse geographic and institutional settings, remain limited.

Moreover, although several FD devices are available, differences in their outcomes remain understudied, particularly in non-comparative, observational contexts. In many clinical centers, device selection depends on availability, operator preference, and anatomical suitability. Seminal studies, such as the PUFS trial, established the safety and efficacy of FD devices in complex aneurysms, providing the foundation for their widespread adoption. In addition, the ISAT trial highlighted the evolution of endovascular approaches, against which newer techniques such as flow diversion can be contextualized (10-12).

2. Objectives

The objective of this study was to systematically evaluate the complications associated with the use of FD devices in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Specifically, the study aimed to document the incidence, types, and outcomes of complications observed in a retrospective, single-center cohort, thereby providing real-world evidence to support clinical decision-making and identify areas requiring further prospective research.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This retrospective, single-center descriptive study was conducted from 2020 to 2023. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval code: IR.ARAKMU.REC.1402.202). All patient data were anonymized, and medical records were used solely for research purposes.

3.2. Participants and Eligibility Criteria

Patients were consecutively selected based on the availability of complete medical records and the following inclusion criteria: The presence of an intracranial aneurysm confirmed by two board-certified neurologists and two board-certified interventional radiologists; aneurysm size ≥ 6 mm; and adequate arterial access, defined as parent artery diameter ≥ 2.5 mm, absence of severe vessel tortuosity, and feasibility of access via femoral or radial route. For previously ruptured aneurysms, patients had to be in stable clinical status [modified Rankin Scale (mRS) ≤ 2] with no acute neurological decline within 72 hours prior to treatment. The exclusion criterion was incomplete medical records.

- Exclusion criterion: Incomplete medical records were considered as an exclusion criterion.

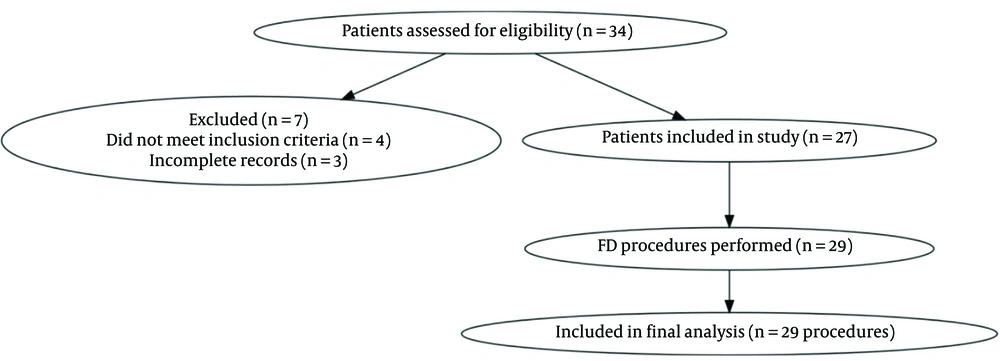

- Recruitment Process: Eligible patients were identified through institutional neurointerventional procedure logs and screened according to the above criteria. Figure 1 shows the patient screening, exclusion, and inclusion process in accordance with STROBE guidelines.

3.3. Interventions (Device Placement Details)

Procedures were performed by experienced interventional neuroradiologists under general anesthesia. A variety of FD devices were used, including the flow re-direction endoluminal device (FRED, MicroVention), DERIVO (Acandis), High-Plane, Surpass Evolve (Stryker), and Vantage (MicroPort). Device selection was based on aneurysm morphology, parent artery size, and operator judgment. Adjunctive coiling was performed at the discretion of the treating physician, typically in cases of wide-neck aneurysms.

3.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of any post-procedural complication, including hemorrhage, thrombosis, stent migration, or new neurological deficit. The secondary outcome was complete aneurysm occlusion, as assessed by follow-up angiography or MR angiography. Follow-up imaging was scheduled at 3 - 12 months post-procedure.

3.5. Data Sources and Collection Process

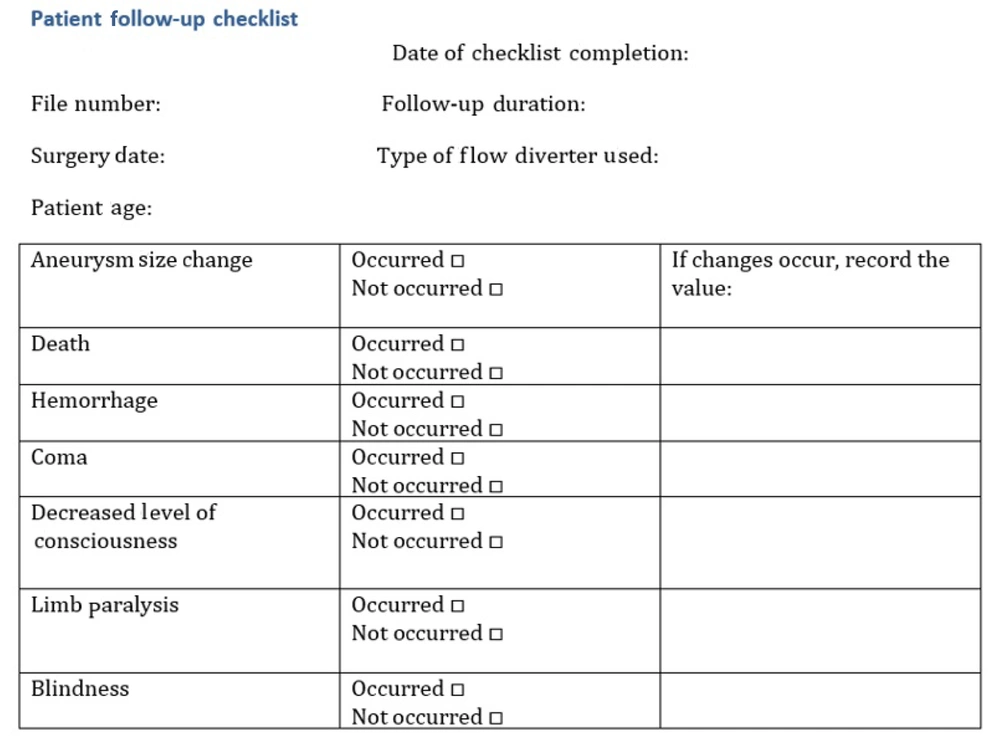

All baseline clinical and imaging data were extracted from hospital records by two independent interventional neuroradiology fellows using a standardized data checklist. Figure 2 illustrates the standardized checklist used for data collection, which helped ensure consistency and minimize missing data.

Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a senior attending neuroradiologist. The diagnosis of aneurysm morphology and location was confirmed by two board-certified neurologists and two board-certified interventional radiologists. Inter-rater agreement for aneurysm classification was > 90%.

3.6. Bias Considerations

Potential sources of bias included the retrospective design, operator-dependent device selection, and incomplete follow-up in some patients. Consecutive case inclusion and standardized data collection were applied to minimize selection and measurement bias.

3.7. Sample Size Justification

The minimum sample size was estimated using complication incidence rates reported by another study to guide descriptive incidence estimation, not for comparative power. The final sample consisted of 27 patients (29 procedures), which provided approximately 80% power to detect a complication incidence of 13.8% with a ± 13% margin of error at a 95% confidence level.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. No inferential statistical tests were performed due to the descriptive design and small sample size.

4. Results

Based on the sample, 35 patient records were reviewed. Of these, 29 procedures involving 27 patients were included in the study. Two patients underwent intervention twice, receiving two FDs. Seven cases were excluded due to incomplete follow-up data, and one case was excluded due to incomplete imaging data. Given the descriptive design and small sample size, no hypothesis testing or between-group comparisons were performed; results are presented as counts, percentages, and summary measures only.

The mean age of patients was 49.4 ± 12.8 years (range: 18 - 82). Nineteen patients (70.4%) were female, and 8 (29.6%) were male. Regarding aneurysm types, 4 cases (14.8%) were dissecting aneurysms, 1 case (3.7%) was a fusiform aneurysm with a wide neck, 1 case (3.7%) was a pseudoaneurysm, and 23 cases (85.2%) were saccular aneurysms. Among the saccular aneurysms, 8 cases (34.8%) were giant aneurysms, 2 cases (8.7%) had a daughter aneurysm, and 3 cases (13.0%) had a wide neck. Overall, 3 aneurysms (11.1%) were ruptured. The mean maximum aneurysm size was 12.0 ± 6.6 mm (range: 3 - 24.7 mm), while the mean minimum aneurysm size was 4.2 ± 1.8 mm (range: 2 - 8 mm; Table 1).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y); range: 18 - 82 | 49.4 ± 12.8 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 20 (74.1) |

| Male | 7 (25.9) |

| Hypertension | 9 (33.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus; patients | 5 (18.5) |

| Smoking history; patients | - |

| Aneurysm type | |

| Saccular | 23 (85.2) |

| Dissecting | 4 (14.8) |

| Fusiform with wide neck | 1 (3.7) |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 1 (3.7) |

| Aneurysm location | 12 (44.4) |

| ICA | |

| MCA | 8 (29.6) |

| ACA | 5 (18.5) |

| BA | 2 (7.4) |

| Previous SAH; patients | 3 (11.1) |

| mRS ≤ 2; patients | 27 (100) |

| Adjunctive coiling performed; procedures | 16 (55.2) |

| Average number of coils per procedure; coils | 2.6 ± 2 |

Abbreviations: ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BA, basilar artery; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

Regarding the types of FDs used, 21 cases (77.8%) received FRED, 3 cases (11.1%) received DERIVO, 2 cases (7.4%) received High-Plane, 2 cases (7.4%) received Surpass Evolve, and 1 case (3.7%) received Vantage. Coiling was used in 16 procedures (55.2%), with a mean of 2.6 ± 2 coils per procedure (range: 1 - 7). Among coiled procedures, the mean flow-diverter length was 22.06 mm. In non-coiled procedures, the mean length was 24.77 mm. These figures are presented descriptively without comparison. The most frequently used FD length was 25 mm in coiled cases and 20 mm in non-coiled cases. The mean diameter of FDs was 4.03 mm in coiled cases and 3.92 mm in non-coiled cases, with the most frequently used diameter being 2.5 mm in coiled cases and 4.5 mm in non-coiled cases.

The aneurysms were located in the internal carotid artery (ICA): 44.4% (including ophthalmic segment, cavernous segment, and paraclinoid segment aneurysms), middle cerebral artery (MCA): 29.6%, anterior cerebral artery (ACA): 18.5%, and basilar artery (BA): 14.8%.

Complications occurred in four patients [13.8%; 4 out of 29 procedures, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.9 - 31.7%], including stent migration (n = 1), intracranial hemorrhage (n = 1), in-stent thrombosis with a fatal outcome (n = 1), and complete carotid artery thrombosis (n = 1). One patient also developed post-procedural blindness (3.4%; 95% CI: 0.1 - 17.8%). Upon review, no technical device failures were identified; complications were more likely related to aneurysm characteristics (e.g., wide neck, ophthalmic segment location), delayed thrombosis, or individual anatomical factors (Tables 2 and 3).

| Complication type | Cases a | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stent migration | 1 (3.4) | Managed without further event |

| In-stent thrombosis | 1 (3.4) | Resulted in death |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 1 (3.4) | Resulted in death |

| Carotid artery thrombosis | 1 (3.4) | Resulted in death |

| Post-procedural blindness | 1 (3.4) | Permanent visual loss |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| Outcome | Patients c | Follow-up status |

|---|---|---|

| 22 at 1 y, 1 at 9 mo, and 1 at 3 m | 24 (82.8) | Completed follow-up imaging (3 - 12 mo) |

| Fatal outcome | 1 (3.4) | No follow up: Intra-procedural thrombosis, death |

| Fatal outcome | 1 (3.4) | No follow-up: SAH, death |

| Fatal outcome | 1 (3.4) | No follow-up: Complete carotid thrombosis, death |

| Died due to other cause | 1 (3.4) | No follow-up: Unrelated death |

| Residual aneurysm at 1 year, no imaging follow-up | 1 (3.4) | No follow-up: Blindness case (residual aneurysm, clinical follow-up only) |

Abbreviation: SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

a Percentages are calculated based on the total number of procedures (n = 27 patients, 29 procedures).

b Reasons for missing follow-up imaging are specified, including procedure-related mortality, unrelated death, and a case of blindness with residual aneurysm managed by clinical follow-up only.

c Values are expressed as No. (%).

Follow-up imaging was available in 24 procedures (82.8%), most commonly at 1 year (91.7%). In the remaining five cases, lack of follow-up was due to procedure-related death (n = 3), unrelated death (n = 1), or clinical follow-up only in the blindness case (n = 1, Table 3). Across device types, patient age and aneurysm sizes appeared broadly similar, though no conclusions were drawn given the limited numbers. Descriptively, complications tended to occur in patients with larger aneurysms, but no statistical analyses were performed.

Among the 24 procedures with complete occlusion, follow-up imaging was performed at 1 year in 22 cases (91.7%), at 9 months in 1 case, and at 3 months in 1 case. Of the five patients without imaging follow-up, three died due to procedure-related complications, one died of unrelated causes, and one had clinical follow-up only due to post-procedural blindness. This patient had an aneurysm located in the ophthalmic segment of the ICA initially measuring 10 × 8 mm, treated with a FRED FD. Follow-up imaging at one year showed a residual aneurysm measuring 5 × 3.5 mm. No technical issues with device placement were identified, and the blindness was attributed to the persistent aneurysm.

Across the different FD types used in this study, patient age and aneurysm sizes appeared broadly similar. However, no conclusions can be drawn due to the small number of cases for non-FRED devices. Patients treated with different FD types appeared to have broadly similar age and aneurysm size profiles, though no formal comparison was performed due to limited sample sizes. Patients with complications tended to have larger aneurysms, although no statistical analysis was performed due to the small sample size.

In terms of safety outcomes, intraoperative or postoperative hemorrhage was observed in one case (3.4%). No cases of limb paralysis were reported. One patient (3.4%) experienced a loss of consciousness, leading to brain death and subsequent mortality. Three patients died due to procedure-related complications (thrombosis and SAH). No subgroup comparison was performed due to the descriptive nature of the study (Table 2).

Regarding efficacy outcomes, complete aneurysm obliteration was observed in 24 out of 29 procedures (82.8%). The mean initial aneurysm size was 6.6 mm (range: 3 - 24.7 mm). The secondary aneurysm size was reduced in most cases (82.8%), with the remaining five cases not requiring re-hospitalization or additional treatment.

The single case of blindness occurred in a patient with an ophthalmic segment ICA aneurysm treated with a FRED device. Additionally, one patient with a wide-neck aneurysm developed blindness, with a residual aneurysm size measuring 5 × 3.5 mm at one-year follow-up (initial size: 10 × 8 mm). The single blindness case occurred in a patient treated with a FRED device. With only one such event, device-specific complication rates were not interpreted.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrated the high efficacy of FDs in treating complex intracranial aneurysms, with a complete aneurysm occlusion rate of 82.8% at follow-up. This observed occlusion rate is consistent with previously published findings, but interpretation should remain cautious due to sample size and study design. The majority of treated aneurysms were saccular (85.2%), with a considerable proportion categorized as giant aneurysms (37.0%), indicating the suitability of FDs for a range of aneurysm morphologies.

Regarding safety, complications occurred in a minority of cases, with a 3.4% incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage and blindness, and a 10.3% overall mortality rate. Similar types of complications have been reported in prior studies, though no direct comparisons were performed in this study.

The causes of mortality, including intra-arterial and complete carotid thrombosis, highlight the importance of careful patient selection, antiplatelet management, and close post-procedural monitoring. In our series, complications such as blindness were not limited to any specific type of FD. This observation may reflect the influence of other factors — such as aneurysm location or individual anatomical variations — on complication risk.

Adjunctive coiling was used in 55.2% of cases, often in wide-neck aneurysms, which may reflect operator preference rather than a confirmed effect on outcomes. However, its potential contribution to thrombotic complications requires further investigation. In our cohort, patient age and gender did not appear to influence the choice of FD. Treatment selection was likely guided by anatomical characteristics and clinical judgment. Overall, our findings reinforce the efficacy of FDs in aneurysm treatment while underscoring the need for careful patient selection and post-procedure surveillance. Future studies should explore long-term outcomes, optimize patient selection criteria, and refine peri-procedural management strategies to minimize complications.

In this cohort, adjunctive coiling was performed in 55.2% of procedures, predominantly in wide-neck aneurysms. While the decision to use coils was based on operator judgment rather than a standardized protocol, this technique is often considered to enhance immediate aneurysm stability and reduce the risk of delayed rupture by promoting early thrombosis within the sac. However, it may also introduce potential risks, such as increased procedural time, higher device manipulation, and altered hemodynamics, which could predispose to thromboembolic events (13). In our study, some thrombotic complications, including in-stent thrombosis and complete carotid artery thrombosis, occurred in patients who had received adjunctive coiling, although the small sample size precludes establishing a causal relationship. These observations underscore the need for further prospective studies to clarify whether adjunctive coiling confers a protective effect or contributes to complication risk in the context of FD treatment.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the relatively small sample size of 27 patients and 29 procedures substantially limits the statistical precision of our complication and mortality rate estimates. These findings should therefore be interpreted cautiously and cannot be generalized to broader patient populations or to all FD devices. Larger multicenter studies are required to validate these observations.

Another important limitation of this study is the incomplete documentation of antiplatelet regimens and the lack of consistent platelet function testing. Because thrombotic complications were among the major adverse events observed, this limitation significantly affects the interpretation of our findings. Variability in dual antiplatelet therapy protocols, dosing, and individual responsiveness (e.g., clopidogrel resistance) could have influenced the occurrence of thrombosis. Without standardized antiplatelet data, it is difficult to determine whether such complications were primarily related to device factors, aneurysm characteristics, or suboptimal antiplatelet coverage. Future prospective studies should incorporate uniform antiplatelet protocols and routine platelet function testing to allow a more accurate assessment of thrombosis risk.

Second, the retrospective and single-center nature of the study introduces potential sources of bias, including limitations in data completeness, standardization, and generalizability. The selection of specific FD devices or the use of adjunctive coiling was based on operator judgment and anatomical factors, not governed by uniform protocols. Third, information on antiplatelet regimens, platelet function testing, or clopidogrel responsiveness was not consistently available, which may influence complication outcomes such as thrombosis.

These limitations highlight the need for larger, multicenter, prospective studies with standardized treatment protocols and longer follow-up to better assess the safety and efficacy of FDs in diverse patient populations. In conclusion, this descriptive, single-center study found a 13.8% overall complication rate and a 10.3% mortality rate following FD treatment of intracranial aneurysms. These findings highlight the need for close procedural monitoring and underscore the importance of larger, prospective studies to further evaluate FD-related complications and long-term outcomes.