1. Background

Thyroid hormones play a vital role in fetal growth, placental function, and neurological development. Hormonal changes in the mother and fetal growth during pregnancy lead to adaptive changes in maternal thyroid function. During pregnancy, numerous changes occur in thyroid gland functions, and thyroid pathologies can lead to adverse consequences for both the fetus and the mother. Pathologies such as impaired fetal neurological development, reduced head circumference, low birth weight, and preterm birth have been linked to thyroid gland dysfunction. Screening for thyroid gland dysfunction during pregnancy varies by region, and there is no consensus (1, 2).

Thyroid gland sizes are influenced by various factors, including gender, age, smoking, iodine intake, and pregnancy. Thyroid hormone production increases during pregnancy due to elevated metabolic demands. Studies exist in which changes in thyroid gland dimensions during pregnancy are evaluated through palpation and ultrasonography (US). The prevailing consensus is that thyroid gland size increases during pregnancy, particularly in regions with iodine deficiency (3-5). Ultrasonography is one of the primary imaging methods used for thyroid gland examination for more than 40 years due to its ease of use, ability to create real-time images, portability, radiation-free nature, and low cost. The importance of US is also very valuable in evaluating thyroid gland diseases.

Two-dimensional shear wave elastography (2D-SWE) is an imaging method that allows the quantitative evaluation of the stiffness of tissues in both kilopascals (kPa) and velocity in terms of meters per second (m/s) (6, 7). The diagnostic value of 2D-SWE has been studied for many different tissues, and its use in thyroid gland diseases is gradually increasing. Reports indicate that incorporating SWE in thyroid gland assessment, as an adjunct to conventional US, proves beneficial in distinguishing between malignant and benign nodules. It has also been demonstrated to contribute to US in non-nodular thyroid gland diseases, such as thyroiditis (7, 8).

2. Objectives

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the thyroid gland in pregnancy using elastography. This study was designed to investigate gestational alterations in thyroid parenchymal stiffness and glandular volume, and to delineate normative trimester-specific values for 2D-SWE assessments of the thyroid gland. We believe that with the widespread use of elastography, knowing trimester-specific reference values in pregnancy may prevent possible incorrect estimations and increase diagnostic accuracy.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Participants

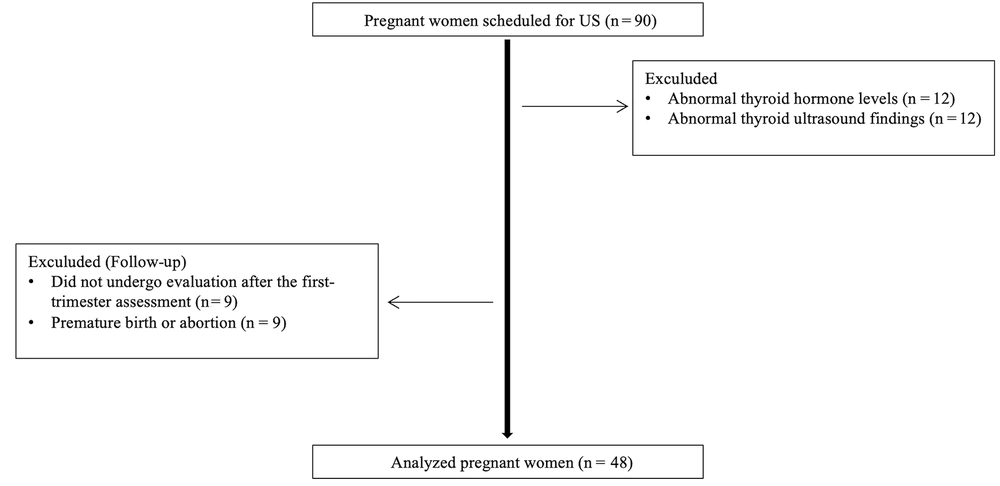

This prospective longitudinal study was conducted among healthy pregnant women who attended the obstetrics and gynecology clinic of our institution between June 2020 and June 2023. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (70632468-050.01.04/2020/548), and written informed consent was secured from all participants prior to enrollment. At baseline, a total of 90 pregnant women who did not have any comorbidities, especially thyroid disorders, and were not taking thyroid medication were included in the study. In addition to routine antenatal evaluations, thyroid US was performed during the first (11 - 14 weeks), second (21 - 24 weeks), and third (31 - 34 weeks) trimesters. Prior to each sonographic assessment, blood samples were collected to measure serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (fT3), and free thyroxine (fT4) levels. Thyroid hormone tests taken in the first trimester were routine tests, and after obtaining the necessary approvals, thyroid hormone samples were taken for study in the second and third trimesters. Participants presenting with abnormal thyroid function tests during the first trimester (n = 12) or pathological findings on thyroid US (n = 12) were excluded. Additionally, eight participants were lost to follow-up after the first trimester, and eight pregnancies ended prematurely due to miscarriage or preterm birth. After these exclusions, the study cohort was finalized with the remaining eligible participants. In conclusion, the study comprised 48 healthy pregnant women with normal B-mode US findings and thyroid functions. Pregnant women included in the study did not differ demographically or clinically from the initially excluded group. Each participant was followed up separately in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy, and laboratory and US evaluations were performed (Figure 1).

3.2. Ultrasound Evaluation of the Thyroid Gland Using B-mode and Two-Dimensional Shear Wave Elastography

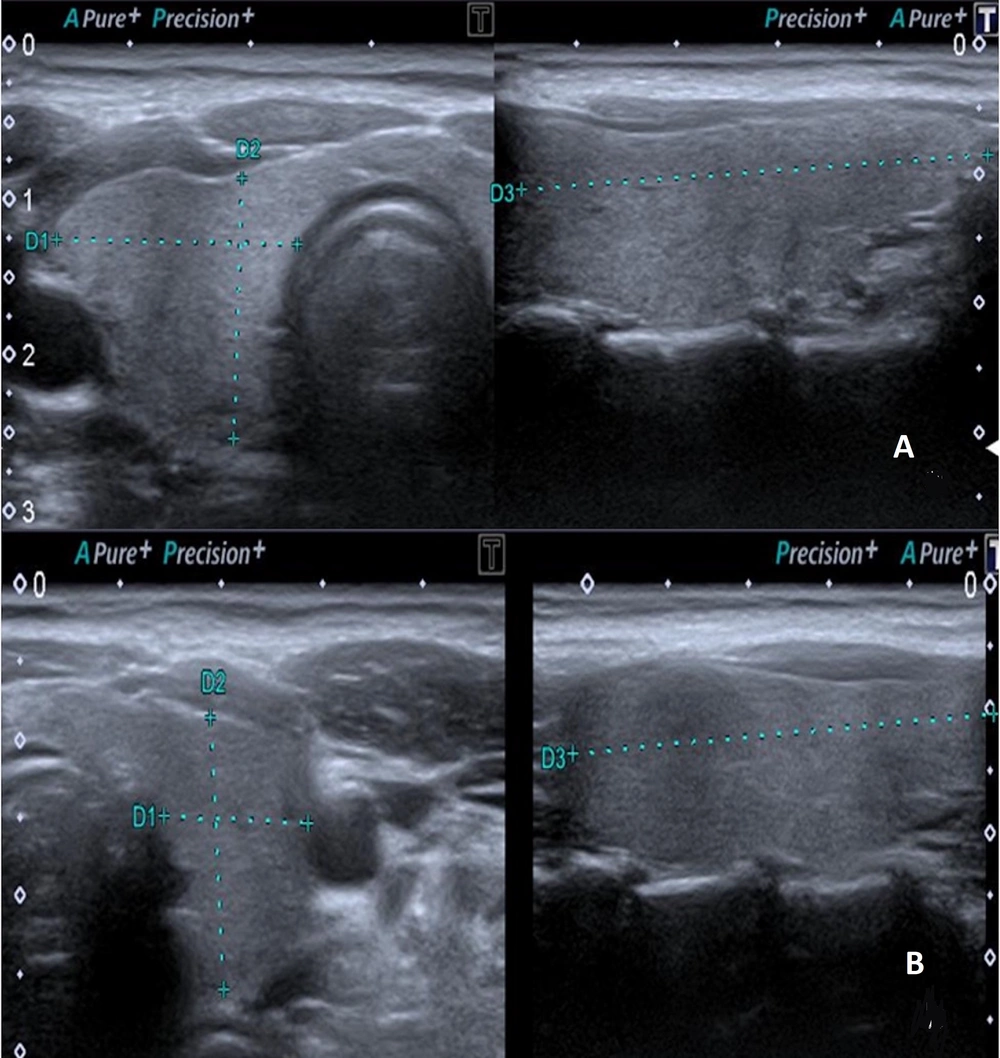

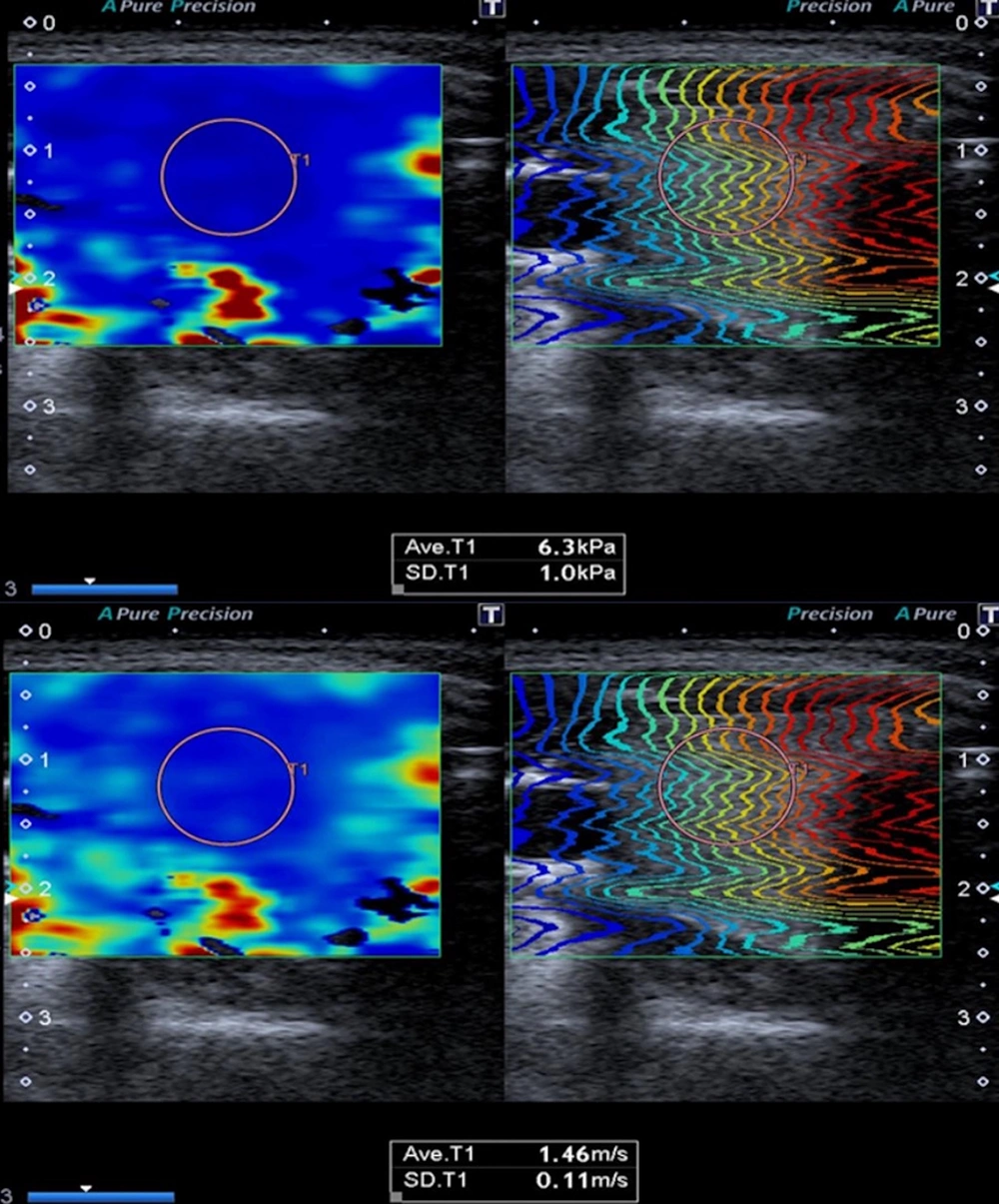

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the thyroid gland was conducted using a Canon Aplio 500 device (Canon Medical System Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a high-frequency (6.2 - 12 MHz, center frequency: 8 MHz) linear transducer. The US examination was performed with the patient in a supine position and the head in slight extension. All measurements were made by a radiologist with eight years of experience in elastography. The dimensions of both thyroid lobes were individually measured in three planes (length × width × height) using gray-scale images. Thyroid lobe volume values were calculated automatically by the device (Figure 2). The thyroid gland was evaluated with B-mode US to examine parenchymal and nodular disease. Ensuring the parallelism of elastography lines in 2D-SWE measurements and utilizing a homogeneous color map to code the thyroid lobe were established as criteria for optimal measurement quality. The 2D-SWE measurements were obtained by outlining a circular region of interest (ROI) in the axial plane for each thyroid lobe. The ROI was accepted as between 5 × 5 mm and 10 × 10 mm, which would be from the region that meets the appropriate criteria (Figure 3). Elastography measurements were obtained from the central part of the parenchyma for each thyroid lobe. A minimum of three measurements were taken from elasticity (kPa) and velocity (m/s) images for each thyroid lobe, and the average of the recorded values was calculated. All measurements for each lobe were made from the same ROI at the same location. Measurements were made in the morning, under a fasting condition of at least 8 hours.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp. released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics are presented as means with standard deviations (SD). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To evaluate changes in thyroid elastography parameters, thyroid volumes, and thyroid hormone levels across the three trimesters, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. The assumption of sphericity was tested using Mauchly’s test, and where violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni adjustment to account for multiple comparisons. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Intra-observer reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), based on a two-way mixed model with consistency type.

4. Results

A total of 48 healthy pregnant women, with a mean age of 28.4 ± 6.0 years, were evaluated in the present study. Mean values for 2D-SWE, thyroid volume, and thyroid hormone levels were calculated across the three trimesters. To evaluate intra-observer reliability, the ICC was calculated using a two-way mixed-effects model with consistency type. The ICC was found to be 0.951 (95% CI: 0.931 - 0.970, P < .001), indicating excellent reliability for repeated measurements on the same tissue by a single observer.

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant overall effects of gestational age on several parameters, including 2D-SWE values, TSH, fT3, and fT4 levels. Although mean thyroid volume tended to increase with gestational age (9.72 ± 4.21 mL in the first trimester, 10.69 ± 4.55 mL in the second, and 11.75 ± 5.2 mL in the third), this change did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1681). Mean 2D-SWE velocities (m/s) significantly decreased across trimesters, from 1.71 ± 0.10 in the first trimester (95% CI: 1.68 - 1.74) to 1.64 ± 0.08 in the second (95% CI: 1.62 - 1.66) and 1.60 ± 0.07 in the third (95% CI: 1.58 - 1.62) (P < 0.0001). Similarly, mean stiffness values (kPa) also declined progressively, with values of 8.98 ± 1.28 (95% CI: 8.61 - 9.35), 8.28 ± 1.18 (95% CI: 7.94 - 8.62), and 8.01 ± 1.16 (95% CI: 7.67 - 8.35) for the first, second, and third trimesters, respectively (P < 0.0001). This downward trend was consistently observed in both right- and left-sided measurements for velocity and kPa.

The TSH levels increased with gestational age, from 1.47 ± 0.74 μIU/mL in the first trimester to 1.75 ± 0.70 and 1.68 ± 0.80 in the second and third trimesters, respectively (P = 0.0399). Both fT3 and fT4 levels significantly decreased over time: Free triiodothyronine dropped from 3.31 ± 0.36 pg/mL to 3.02 ± 0.28 pg/mL, and fT4 from 0.83 ± 0.10 ng/dL to 0.72 ± 0.09 ng/dL (both P < 0.0001).

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a large effect of gestational age on mean (η2 = 0.442), right (η2 = 0.470), and left (η2 = 0.408) 2D-SWE velocity. Moderate effects were observed for mean (η2 = 0.355), right (η2 = 0.364), and left (η2 = 0.348) elasticity (kPa), while changes in thyroid volume showed small effect sizes (e.g., η2 = 0.043 for total volume) (Table 1). Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed statistically significant differences in mean 2D-SWE velocity (m/s) across all trimesters (1st vs 2nd, 1st vs 3rd, and 2nd vs 3rd; all P < 0.05). Additionally, a significant difference was observed in left-sided 2D-SWE velocity between the first and third trimesters, and in total thyroid volume between the second and third trimesters. No other post-hoc comparisons reached statistical significance after adjustment, including those for TSH, fT3, and fT4 levels (Table 2).

| Variables | First | Second | Third | P-value | Partial Eta-squared values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right volume (mL) | 5.68 ± 2.41 | 6.16 ± 2.7 | 6.78 ± 3.2 | 0.3491 | 0.045 |

| Left volume (mL) | 4.04 ± 1.97 | 4.52 ± 2.07 | 4.96 ± 2.24 | 0.4741 | 0.042 |

| Total volume (mL) | 9.72 ± 4.21 | 10.69 ± 4.55 | 11.75 ± 5.2 | 0.1681 | 0.043 |

| Right elasticity (kPa) | 8.82 ± 1.14 | 8.37 ± 0.89 | 7.68 ± 1.03 | < 0.0001 | 0.364 |

| Right velocity (m/s) | 1.72 ± 0.12 | 1.67 ± 0.09 | 1.60 ± 0.1 | < 0.0001 | 0.47 |

| Left elasticity (kPa) | 8.71 ± 1.3 | 7.92 ± 0.78 | 7.60 ± 0.63 | < 0.0001 | 0.348 |

| Left velocity (m/s) | 1.71 ± 0.12 | 1.61 ± 0.10 | 1.60 ± 0.06 | < 0.0001 | 0.408 |

| Mean elasticity (kPa) | 8.77 ± 1 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.7 | < 0.0001 | 0.355 |

| Mean velocity (m/s) | 1.71 ± 0.1 | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 1.60 ± 0.07 | < 0.0001 | 0.442 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 1.47 ± 0.74 | 1.75 ± 0.70 | 1.68 ± 0.80 | 0.0399 | 0.065 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 3.31 ± 0.36 | 3.05 ± 0.32 | 3.02 ± 0.28 | < 0.0001 | 0.204 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 0.83 ± 0.10 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | < 0.0001 | 0.307 |

Abbreviations: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b P-values refer to overall significance based on repeated-measures ANOVA.

| Variables | Comparison | Raw P-value | Bonferroni adjusted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right volume (mL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.0377 | 0.113 |

| Right volume (mL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.8847 | 1.0 |

| Right volume (mL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.0379 | 0.1136 |

| Left volume (mL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.7874 | 1.0 |

| Left volume (mL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.1344 | 0.4031 |

| Left volume (mL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.2746 | 0.8237 |

| Total volume (mL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.4518 | 1.0 |

| Total volume (mL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.1188 | 0.3565 |

| Total volume (mL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.0127 | 0.0382 |

| Right elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 2 | 0.4262 | 1.0 |

| Right elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 3 | 0.6835 | 1.0 |

| Right elasticity (kPa) | 2 vs 3 | 0.6779 | 1.0 |

| Right velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 2 | 0.6377 | 1.0 |

| Right velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 3 | 0.8381 | 1.0 |

| Right velocity (m/s) | 2 vs 3 | 0.8259 | 1.0 |

| Left elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 2 | 0.8486 | 1.0 |

| Left elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 3 | 0.0587 | 0.176 |

| Left elasticity (kPa) | 2 vs 3 | 0.1003 | 0.3009 |

| Left velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 2 | 0.0466 | 0.1398 |

| Left velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 3 | 0.0098 | 0.0295 |

| Left velocity (m/s) | 2 vs 3 | 0.7363 | 1.0 |

| Mean elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 2 | 0.1368 | 0.4103 |

| Mean elasticity (kPa) | 1 vs 3 | 0.4419 | 1.0 |

| Mean elasticity (kPa) | 2 vs 3 | 0.4214 | 1.0 |

| Mean velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 2 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Mean velocity (m/s) | 1 vs 3 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Mean velocity (m/s) | 2 vs 3 | 0.024 | 0.024 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.8911 | 1.0 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.8766 | 1.0 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.9856 | 1.0 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.723 | 1.0 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.3112 | 0.9335 |

| fT3 (pg/mL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.462 | 1.0 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 1 vs 2 | 0.7585 | 1.0 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 1 vs 3 | 0.7724 | 1.0 |

| fT4 (ng/dL) | 2 vs 3 | 0.9896 | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free thyroxine.

a Differences showing significant changes for some pairwise comparisons.

b P-values represent the adjusted significance levels after controlling for multiple comparisons.

c 1, 2, and 3 refer to successive trimesters.

5. Discussion

The increased production of thyroxine-binding globulin, transplacental transfer of iodide, and enhanced renal iodide excretion affect both thyroid gland functions and volume during pregnancy (9). Numerous studies have been conducted in regions with varying iodine levels to investigate alterations in thyroid gland size during pregnancy. In the review published by Berghout et al., which encompassed studies involving both iodine-deficient and iodine-sufficient pregnant women, it was observed that thyroid size increased during pregnancy in iodine-deficient regions; however, there was no significant increase in thyroid size in iodine-sufficient regions (3, 10, 11). In the guideline from the American Thyroid Association on thyroid diseases during pregnancy, it was reported that due to the increased thyroid hormone production necessitated by elevated fetal and maternal requirements, a 10% increase in thyroid size can be observed in iodide-sufficient regions, while iodide-deficient areas may experience a more pronounced 20 - 40% increase (12). In the study of Sahin et al., a significant increase was identified in thyroid volume during pregnancy in the region characterized by severe iodine deficiency (13). Fister et al., in their longitudinal prospective study on 118 pregnant women in the iodine-sufficient Slovenian population, reported that thyroid gland sizes increased significantly between the first and third trimesters and decreased in the postpartum period (14). In Elebrashy et al.’s study of the Egyptian women population, although the thyroid gland sizes were higher in pregnant women, no significant difference was found compared to the non-pregnant group (5). In the study of Henrietta et al. on the Nigerian female population, it was reported that thyroid gland sizes increased in pregnant women in iodine-sufficient regions, and this increase was gradual during trimesters (15). In the study by Vannucchi et al. within the mild iodine-insufficiency region, a significant increase in thyroid gland size was reported during pregnancy (16).

In our study, although a progressive increase in thyroid gland size was observed across trimesters, this change did not reach statistical significance in the overall repeated-measures ANOVA. However, Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase in total thyroid volume between the second and third trimesters. These findings suggest that morphological changes in the thyroid may become more pronounced in late pregnancy. Thyroid volumes, as categorized by trimesters, were found to be greater than those reported in the studies by Elebrashy et al. (5) and Vannucchi et al. (16), consistent with the findings of Fistler et al. (14), but smaller than the observations of Sahin et al. (13). Thyroid gland enlargement is commonly observed during pregnancy, typically returning to baseline dimensions postpartum. This increase is predominantly attributed to the rise in extracellular fluid and blood volume that occurs as part of the physiological adaptations to pregnancy. The potential impact of TSH on the increase in thyroid gland size cannot be disregarded, particularly considering that this influence has been reported as negligible (16). The TSH levels, which tend to be relatively low in the first trimester due to the suppression of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), are anticipated to rise during the later weeks of gestation. Meanwhile, T3 and T4 levels decrease due to elevated thyroid-binding globulin levels during pregnancy (17, 18). Likewise, our study revealed significantly higher TSH values and notably lower T3 and T4 values during the later stages of pregnancy, as compared to the first trimester.

The 2D-SWE is an imaging method using acoustic radiation force. Using shear waves, information is obtained from multiple regions instead of a single focal point. The 2D-SWE produces shear waves along either parallel or vertical dimensions under dynamic stress. Measuring the velocity of these waves provides both qualitative and quantitative insights into tissue elasticity. This technique’s advantage is that anatomical and elastographic evaluation can be performed simultaneously, thanks to the real-time elastography color map superimposed on the B-mode image (19, 20). Elastography is increasingly being utilized for evaluating thyroid gland pathologies, particularly in distinguishing between benign and malignant thyroid nodules. Numerous studies have been documented in the literature discussing the role of elastography in this context (21-24). Several studies have investigated the application of 2D-SWE in parenchymal diseases of the thyroid gland, including acute-subacute thyroiditis, Riedel’s thyroiditis, Hashimoto’s, and Graves’ disease. These studies have identified heightened elastography values in areas affected by thyroiditis when compared to the healthy thyroid gland. This elevation in elastography values was attributed to enhanced tissue stiffness resulting from inflammation and fibrosis (7, 25, 26).

Various studies have presented varying ranges of elasticity (kPa) (9-19) and velocity (m/s) (1.2 - 2) values for the normal thyroid gland using the 2D-SWE method. Mean 2D-SWE values for the healthy control group were reported as 12.49 ± 3.23 kPa and 1.94 ± 0.23 m/s in the study by Kara et al., 10.97 ± 3.1 kPa in the study by Arda et al., and 9.5 ± 3.6 kPa in the study by Herman et al. (7, 27, 28). In our study, we computed the mean 2D-SWE values for all three trimesters among healthy pregnant women who exhibited no thyroid gland pathology on ultrasound and had normal laboratory findings. To our knowledge, no other studies are available in the literature that focus on thyroid gland elastography in pregnant women. Consequently, when compared to measurements from non-pregnant healthy control groups as documented in existing literature, the mean kPa and m/s values observed in our study for all three trimesters were marginally lower but remained within the realm of normal ranges. Furthermore, our study identified a decline in elastography values during the latter stages of pregnancy. As far as we know, decreased thyroid gland stiffness has only been reported in cystinosis cases in the literature. It has been reported that the reason for the decrease in tissue stiffness in these cases may be the loosening of extracellular matrix fibers and adhesions between cells, leading to a decrease in tissue stiffness (29). This situation in our study may be due to the changes mentioned above. Still, it may also be attributed to the fact that the enlargement of the thyroid gland during pregnancy may be associated with an increase in extracellular fluid and blood volume. We believe that with the widespread use of elastography in thyroid imaging, knowing the physiological elastography changes that occur during pregnancy and the normal elastography values for all three trimesters can prevent possible incorrect predictions, especially overdiagnosis, and increase the awareness of radiologists.

Several limitations were present in our study. Comparative analysis of our results was not feasible due to the absence of prior studies investigating the use of 2D-SWE and its quantitative data on the thyroid gland during pregnancy. While the study included pregnant women with normal thyroid hormone test results, it is noteworthy that the assessment of iodine status was lacking. Moreover, other important confounding variables such as Body Mass Index (BMI) and parity were not recorded or adjusted for in the analysis. These factors are known to potentially affect thyroid function and elasticity measurements and may have influenced the results. The examinations were conducted by a single experienced radiologist, precluding the assessment of interobserver variability. Additional limitations of our study encompass the relatively small sample size and the absence of pre-pregnancy and post-pregnancy assessments for the participants. This may be the subject of future research. Notwithstanding these limitations, the significance of our study lies in its longitudinal prospective design, which facilitated the comprehensive tracking of dynamic alterations in thyroid gland volume and elastography values across all pregnancy trimesters.

In conclusion, our study is one of the few longitudinal prospective studies in the literature in which the thyroid gland was evaluated sonographically in pregnant women. We quantitatively demonstrated, with objective numerical data, a significant decrease in thyroid elastography values during pregnancy, while thyroid volume exhibited a non-significant tendency to increase. However, further studies are needed in larger populations, with postpartum follow-ups and with pregnant women diagnosed with thyroid disease.