1. Background

Friedreich’s ataxia (FA), or Friedreich's recessive disease ataxia (FRDA), is the most prevalent inherited ataxia, caused by a GAA trinucleotide repeat expansion in the FXN gene, leading to frataxin deficiency and mitochondrial dysfunction (1). It has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 50,000 individuals (2). While FRDA primarily manifests with progressive ataxia, dysarthria, and sensory neuropathy, cardiac involvement, especially hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), is a major contributor to morbidity and the leading cause of mortality in this population (3, 4). Cardiac abnormalities such as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), systolic dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis are present in approximately 75% of FRDA patients (5, 6). The cardiac phenotype in FRDA is heterogeneous and often progresses silently. Although systolic function tends to remain preserved in early stages, later progression can lead to rapid functional decline and heart failure (7). Disease severity correlates more strongly with GAA repeat length and age at symptom onset than with neurological disability or disease duration (8, 9).

Despite its clinical significance, cardiac assessment in FRDA remains challenging due to limitations in physical examination and echocardiographic visualization, particularly in patients with skeletal deformities or advanced neurologic disability (10). Recent advancements in cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging offer novel approaches to evaluating FRDA-related cardiomyopathy. The CMR enables precise quantification of myocardial mass and function, and techniques such as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and T1 mapping facilitate early detection of myocardial fibrosis even before clinical symptoms or echocardiographic abnormalities emerge (11-13).

While prior studies have characterized cardiac involvement in FRDA using CMR, most have focused on large cohorts or cross-sectional evaluations (6, 12). To date, limited data are available on the individualized cardiac phenotypes captured through comprehensive tissue characterization techniques.

2. Objectives

This case series addresses this gap by presenting detailed CMR findings in four genetically confirmed FRDA patients. It emphasizes the clinical value of advanced CMR, including LGE and mapping, in identifying subclinical fibrosis, stratifying risk, and guiding cardiac management in this high-risk population.

3. Patients and Methods

This retrospective, single-center, consecutive case series screened all patients with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of FRDA who were referred to our pediatric and adult inherited cardiomyopathy clinic between January 2021 and December 2022. The final study cohort consisted of all patients from this referral pool who met the inclusion criteria and subsequently underwent a clinically indicated CMR examination within the study period. No eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria were excluded from the analysis. All patients were managed according to standard clinical practice. Case series designs such as this are commonly used in rare diseases to characterize phenotype variability and guide future research directions (14). In addition, CMR is increasingly recommended for comprehensive cardiac assessment in FRDA due to its ability to detect both hypertrophy and fibrosis non-invasively (15).

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

All eligible patients were required to have a genetically confirmed diagnosis of FA, specifically defined as the presence of biallelic FXN GAA repeat expansions of 90 or more repeats. Participants were required to be between 6 and 25 years of age at the time of their CMR examination. Additionally, they had to demonstrate the ability to cooperate fully with the CMR procedure without the need for general anesthesia.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if they had any standard contraindications to CMR. These included the presence of implanted non-mitral regurgitation (MR)-conditional devices, severe claustrophobia, or an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Other exclusion criteria comprised a history of prior cardiac surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention, as well as any known infiltrative cardiomyopathies unrelated to FA — such as cardiac amyloidosis or sarcoidosis. Finally, cases with insufficient CMR image quality, defined as having two or more non-evaluable myocardial segments based on standard quantitative analysis, were also excluded.

The LVH was defined as an end-diastolic wall thickness measurement of ≥ 12 mm in any myocardial segment, as assessed on short-axis cine steady-state free precession (SSFP) images. Myocardial fibrosis was characterized using two distinct criteria. First, the presence of LGE was identified as focal or patchy areas of hyperenhancement located in the sub-epicardial or mid-wall myocardium, with a signal intensity greater than 2 standard deviations above the mean signal of remote, non-enhanced reference tissue. Second, diffuse fibrosis was defined by an elevated native T1 time greater than 1,100 ms (at 1.5 T) or an extracellular volume (ECV) fraction exceeding 28%.

3.3. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Acquisition Protocol

All imaging was performed using a 1.5 Tesla MRI system (Magnetom Aera, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 16-channel phased-array cardiac coil for optimized signal-to-noise ratio (16). Multi-planar SSFP cine sequences were acquired, including a contiguous short-axis stack (from mitral valve annulus to apex) and standard 2-, 3-, and 4-chamber views. Imaging parameters were: Slice thickness 6 mm, interslice gap 4 mm, time repetition (TR) 37 ms, time echo (TE) 1.3 ms, flip angle 70°, matrix 256 × 192, and temporal resolution ≤ 45 ms (17).

The LGE was assessed using a 2D inversion-recovery gradient-echo sequence acquired 10 - 15 minutes after intravenous administration of gadobutrol (0.15 mmol/kg) at a flow rate of 3 mL/s followed by a 20 mL saline flush. Slice thickness was 8 mm. Inversion time was optimized individually using a Look-Locker sequence to null normal myocardium (13).

Native and post-contrast T1 mapping were performed using a Modified Look-Locker Inversion Recovery (MOLLI) sequence:

1. Native: 5s(3s)3s scheme.

2. Post-contrast: 4s(1s)3s(1s)2s scheme (acquired 15 minutes post gadolinium).

Both were obtained in mid-ventricular short-axis and 4-chamber views. Hematocrit was measured within 2 hours of the scan to calculate ECV fraction (13).

T2 mapping (Myocardial Edema Assessment) was performed using a T2-prepared single-shot SSFP sequence with echo times of 0, 24, and 55 ms in mid-ventricular short-axis and 4-chamber views to detect myocardial edema (18).

3.4. Post-processing and Diagnostic Criteria

The CMR images were analyzed using commercial software (cvi42 v.5.13, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, Canada). Left ventricular (LV) volumes and mass were indexed to body surface area (BSA); papillary muscles were excluded from myocardial mass. The LV hypertrophy was defined as any segment ≥ 12 mm in end-diastole. The presence of focal fibrosis was assessed using LGE imaging and was defined as regions of hyperenhancement with a signal intensity greater than 2 standard deviations above that of remote myocardium. Diffuse fibrosis was defined as native T1 > 1100 ms or ECV > 28% (1.5 T, MOLLI), adjusted to institutional reference values. Myocardial edema was defined as segmental T2 > 55 ms (19).

Due to the small cohort size in this study, formal inter- and intra-observer reproducibility was not reassessed in the present four cases. Instead, we adhered to a pre-defined analysis protocol that had been previously validated. This protocol's reproducibility was assessed on a separate external cohort of 10 FA cases, which showed excellent agreement [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.90 for LV mass and > 0.85 for native T1 and ECV], consistent with society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (SCMR) recommendations. All quantitative measurements in the current study were performed by the same analysts using the same software and identical methodologies to ensure consistency and comparability with the established reproducibility metrics (16).

3.5. Ethics

The study was approved by the Rajaie Cardiovascular Institutional Review Board (IRB-2020-127). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or legal guardians.

4. Results

A total of four patients with genetically or clinically confirmed FA were included in this case series (two females, two males). The mean age was 15.5 ± 5.9 years (range: 8 - 22 years), and the mean BSA was 1.43 ± 0.39 m2. The LVH was observed in three of four patients (75%), most frequently involving the basal or mid-septal segments. The mean maximal LV wall thickness across the cohort was 15.9 ± 3.2 mm. The LV systolic dysfunction [defined as left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%] was present in three patients (75%), with a mean LVEF of 49.8 ± 6.7%. Right ventricular (RV) systolic function was preserved in all patients (mean RVEF = 57.5 ± 3.6%). The mean LV Mass Index was 93 ± 27 g/m2.

The LGE was positive for patchy myocardial fibrosis in three of the four patients (75%), with distribution predominantly in the septal and inferolateral walls. One patient demonstrated no fibrosis and had normal T1/T2 mapping values, consistent with absent or minimal cardiac involvement. Moderate valvular regurgitation [aortic, MR, and tricuspid (TR)] was identified in one patient. Additionally, scoliosis was documented in one case, reflecting the multisystem nature of FA.

This study demonstrated a high prevalence of concentric LVH, reduced systolic function, and patchy myocardial fibrosis consistent with cardiac involvement in FA. These findings underscore the heterogeneity of cardiac manifestations in FA, ranging from subclinical hypertrophy without fibrosis to extensive myocardial involvement with functional impairment.

4.1. Cases

4.1.1. Case 1

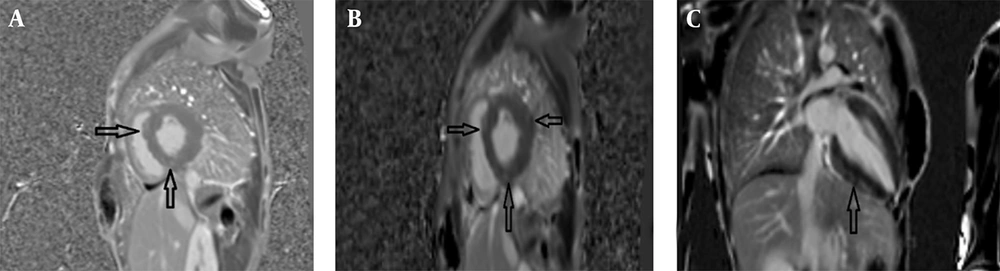

The first patient was an 18-year-old female with a height of 159 cm, weight of 40 kg, and a BSA of 1.32 m2, who presented with progressive ataxia and speech disorder, consistent with a clinical diagnosis of FA. Cardiac MRI was performed utilizing a standardized protocol that included SSFP cine imaging, LGE, and T1/T2 mapping sequences. Morphological assessment revealed concentric LVH with a maximum wall thickness of 13 mm in the basal septum, alongside interatrial septal hypertrophy. Functional analysis indicated a normal LV size with mildly reduced systolic function (LVEF = 46%) and mildly reduced RV function (RVEF = 52%); the LV Mass Index was calculated at 117 g/m2. Tissue characterization demonstrated patchy myocardial fibrosis in multiple segments on LGE imaging, while T2 mapping ruled out active myocardial inflammation or edema (Figure 1). Additionally, thoracic imaging noted mild scoliosis. In summary, the constellation of concentric LVH, patchy myocardial fibrosis, and concomitant neurologic symptoms was consistent with established cardiac involvement in FA.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) of an 18-year-old female with Friedreich’s ataxia (FA); late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging showing patchy myocardial fibrosis across multiple segments: A, Short-axis phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) LGE image demonstrating focal areas of mid-wall enhancement (black arrows); B, Corresponding short-axis Magnitude LGE image indicating focal areas of mid-wall enhancement, no evidence of myocardial inflammation or edema (black arrows); C, 2-Chamber Magnitude LGE image further highlighting areas of patchy fibrosis (black arrow).

4.1.2. Case 2

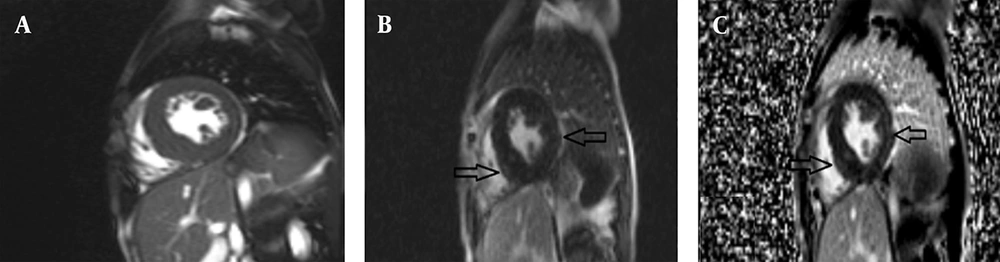

The second case involved an 8-year-old male (height: 120 cm, weight: 25 kg, BSA: 0.92 m2) with symptoms of ataxia, mild speech disorder, and a relevant family history, having a sister (case 1) with similar manifestations. The cardiac MRI protocol was identical, encompassing SSFP cine, LGE, and mapping sequences. Imaging identified mild LV enlargement with concentric LVH, exhibiting a maximum mid-inferoseptal wall thickness of 21 mm. Functionally, there was mildly reduced LV systolic function (LVEF = 46%, EDVI = 105 mL/m2) but normal RV size and function (RVEF = 60%); the LV Mass Index was 115 g/m2. Tissue characterization via LGE revealed diffuse patchy myocardial fibrosis in multiple segments (Figure 2). Collectively, the pronounced LVH, presence of patchy fibrosis, and the neurologic profile confirmed the diagnosis of cardiac involvement in FA.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) of an 8-year-old male with Friedreich’s ataxia (FA): A, Short-axis cine balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP) image demonstrating concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (maximum thickness:21mm) with relatively preserved cavity size; B, Short-axis Magnitude LGE image showing patchy mid-wall enhancement involving multiple myocardial segments consistent with diffuse myocardial fibrosis (arrows); C, Short axis phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) image revealing patchy mid-wall enhancement (arrows) involving multiple myocardial segments, consistent with diffuse myocardial fibrosis.

4.1.3. Case 3

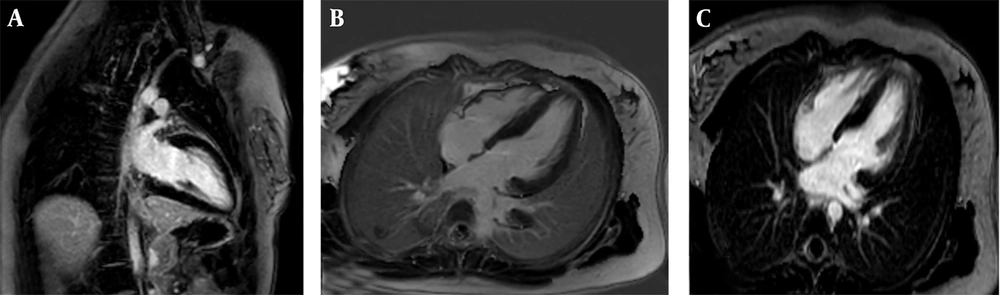

A 14-year-old female (height: 159 cm, weight: 60 kg, BSA: 1.6 m2) with a clinical diagnosis of FA but no significant extra-cardiac symptoms underwent cardiac MRI with the standard protocol. Morphological evaluation showed localized LVH in the mid-inferior septum with a maximum wall thickness of 14.6 mm. Both LV and RV size were normal with preserved systolic function (LVEF = 61%, RVEF = 58%); the LV Mass Index was 58 g/m2. Critically, tissue characterization found no significant fibrosis on LGE, and T1/T2 mapping values were within normal limits, effectively ruling out diffuse fibrosis or active inflammation (Figure 3). These findings suggested only mild cardiac involvement in FA for this patient.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) of a 14-year-old female with Friedreich’s ataxia: A, 2-Chamber Magnitude late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging showing no significant fibrosis; B, 4-Chamber phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) LGE image is within normal limits, indicating no diffuse fibrosis: C, 4-Chamber magnitude LGE images showing no significant fibrosis and LVH with maximum thickness :14.5mm, ruling out inflammation.

4.1.4. Case 4

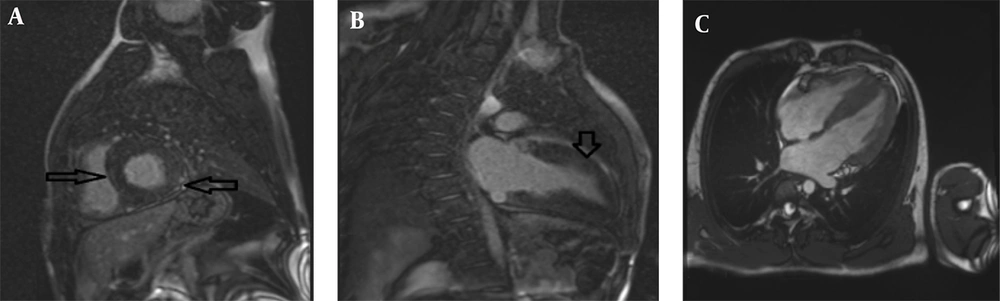

The fourth patient was a 22-year-old male (height: 170 cm, weight: 73 kg, BSA: 1.87 m2) with FA but without significant neurological progression. Following the standardized cardiac MRI protocol, morphological analysis demonstrated concentric LVH with a maximum wall thickness of 15 mm in the basal anterior septum. Functional status was notable for normal LV size with mildly reduced systolic function (LVEF = 46%), and normal RV size and function (RVEF = 60%); the LV Mass Index was 82 g/m2. Moderate aortic (AI), MR, and TR regurgitation were also observed. Tissue characterization identified patchy fibrosis in multiple myocardial segments on LGE imaging (Figure 4). In conclusion, the imaging findings, including hypertrophy, fibrosis, and valvular regurgitation, were consistent with significant cardiac involvement in FA.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) of a 22-year-old male with Friedreich’s ataxia (FA): A, Short axis phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging revealing patchy fibrosis in multiple myocardial segments with arrows indicating affected areas; B, 2-Chamber PSIR LGE imaging further highlighting the extent of fibrosis in a different plane; C, Corresponding 4chamber cine steady-state free precession (SSFP) image demonstrating left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with maximum 15 mm thickness.

All patients' comparative summary of clinical and CMR findings are presented in Table 1.

| Patient no. | Age (y) | Sex | BSA (m2) | LVEF (%) | RVEF (%) | LV Mass Index (g/m2) | Max LV wall thickness (mm) | LVH pattern | LGE fibrosis | T1/T2 mapping | Neurologic symptoms | Additional notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | F | 1.32 | 46 | 52 | 117 | 13 (basal septum) | Concentric LVH | Patchy, multiple segments | T2: Normal | Ataxia, dysarthria | Interatrial septal hypertrophy; mild scoliosis |

| 2 | 8 | M | 0.92 | 46 | 60 | 115 | 21 (mid-inferoseptum) | Concentric LVH | Diffuse patchy | - | Ataxia, mild speech disorder | Sibling of case 1 |

| 3 | 14 | F | 1.60 | 61 | 58 | 58 | 14.6 (mid-inferior septum) | Localized LVH | Absent | Normal | FA, no extracardiac symptoms | - |

| 4 | 22 | M | 1.87 | 46 | 60 | 82 | 15 (basal anterior septum) | Concentric LVH | Patchy, multiple segments | - | FA without neurological progression | Moderate AI, MR, and TR |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; RVEF, right ventricle ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular; LVH, left ventricle hypertrophy; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; FA, Friedreich's ataxia; AI, aortic regurgitation; MR, mitral regurgitation; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

5. Discussion

The FRDA is a multisystemic neurodegenerative disorder in which cardiac disease remains the most common cause of premature mortality. The cardiac phenotype of FRDA includes concentric LVH, diastolic dysfunction, and diffuse myocardial fibrosis, even in the absence of overt symptoms (3). In our case series, all four patients demonstrated various degrees of cardiac involvement, highlighting the clinical heterogeneity of FRDA cardiomyopathy. Myocardial fibrosis in FRDA, detectable through CMR techniques such as T1 mapping and LGE, is a hallmark of disease progression and a predictor of adverse outcomes (6). In particular, native T1 elevation and increased ECV correlate with the extent of fibrotic remodeling and serve as valuable non-invasive biomarkers for early detection (13, 20).

Two of our patients demonstrated significantly elevated native T1 values and non-ischemic LGE patterns, suggesting diffuse interstitial fibrosis even in the absence of systolic dysfunction. The pathophysiology underlying cardiac involvement in FRDA is rooted in mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in impaired oxidative phosphorylation, iron accumulation, and cellular energy deficits in cardiomyocytes (2). This leads to myocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, and eventual decline in both diastolic and systolic function. As previously reported, diastolic dysfunction often precedes systolic impairment and may remain subclinical for years (7). This emphasizes the importance of advanced imaging modalities in identifying preclinical cardiac changes.

Our findings align with prior longitudinal studies indicating that cardiac phenotype progression is more closely related to age at onset and GAA repeat length than to neurologic severity or disease duration (9). These genotype-phenotype correlations may help guide individualized monitoring strategies and prognostication. Additionally, FRDA patients with diabetes or severe scoliosis, as seen in our cohort, may be at higher risk for accelerated cardiac decline (10).

A key strength of our study lies in the comprehensive use of CMR imaging. Techniques such as LGE and T1 mapping enable a tissue characterization approach, offering insights beyond conventional echocardiography. Previous studies have shown that myocardial fibrosis detected on CMR correlates with electrocardiographic abnormalities and increased arrhythmic risk in FRDA (12). In our series, subepicardial and mid-wall LGE were observed, patterns typically associated with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, supporting previous histopathologic and imaging evidence (21).

This case series highlights the phenotypic heterogeneity of cardiac involvement in FRDA, emphasizing the critical role of advanced CMR imaging in delineating myocardial structure and function. We observed a spectrum of cardiac manifestations — from concentric LVH with preserved EF and no fibrosis (case 3) to advanced cardiomyopathy with extensive fibrosis and reduced systolic function (cases 1, 2, and 4). These variations underscore the importance of detailed imaging assessments in identifying clinically meaningful cardiac differences, which may otherwise remain subclinical.

Our observations align with earlier echocardiographic and autopsy-based studies that reported concentric LVH as a hallmark of FRDA, contrasting with the asymmetric hypertrophy typical of sarcomeric HCM (5, 7, 22). While echocardiography has traditionally been the modality of choice, it may underestimate the burden of myocardial fibrosis and cannot reliably assess diffuse interstitial changes (9). The CMR, particularly LGE and native T1 mapping, allows for the identification of both focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis. Our findings confirm the utility of these techniques in uncovering pathology not detectable by conventional imaging.

Importantly, the disparity between cases — especially between case 3 and the others — may be related to differing disease durations, frataxin expression levels, or mitochondrial dysfunction thresholds, though these were not quantified in our series. Prior studies have shown a correlation between GAA repeat length and cardiac severity (7, 20), suggesting that genetic profiling combined with imaging may enhance risk stratification. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of our analysis and the lack of genetic data, such correlations remain speculative in our cohort.

The CMR-based myocardial fibrosis is increasingly recognized as a strong predictor of adverse outcomes in various cardiomyopathies, including FRDA. In the largest longitudinal FRDA cohort to date, Pousset et al. demonstrated that cardiac involvement was the major determinant of mortality, with myocardial fibrosis being a critical prognostic factor (9). In our series, reduced EF and LGE positivity were observed in the same individuals, further supporting their prognostic interplay. Unfortunately, due to the absence of long-term follow-up in our cohort, we could not establish a direct link between fibrosis and clinical outcomes.

The clinical management implications of these findings are considerable. Current consensus guidelines for HCMs recommend implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) in high-risk patients with fibrosis, reduced EF, or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (23). Similar risk-guided strategies could be adapted for FRDA, particularly in those with significant LGE burden. Moreover, early identification of cardiac involvement using CMR may prompt closer monitoring, lifestyle adjustment, and potential pharmacologic interventions aimed at mitigating myocardial remodeling.

This case series demonstrates the heterogeneity of cardiac involvement in FA and affirms the value of CMR imaging in unmasking myocardial fibrosis and LVH, even in the early or subclinical stages. Based on our findings, we recommend that CMR — particularly when including LGE and T1 mapping — be considered an essential component of baseline and longitudinal cardiac evaluation in FRDA patients, regardless of echocardiographic findings. Clinicians should maintain a high Index of Suspicion for cardiac involvement in FRDA and consider early imaging even in asymptomatic individuals. Identifying myocardial fibrosis early may inform decisions regarding pharmacologic therapy, exercise restriction, or more intensive cardiac monitoring.

Future research in FRDA cardiomyopathy should focus on several key objectives. Firstly, there is a critical need to establish standardized, CMR-based risk stratification models specific to the FRDA population. Concurrently, studies must validate the prognostic value of quantitative biomarkers, specifically fibrosis burden and LV mass, as independent predictors of clinical outcomes. Furthermore, interventional trials are warranted to investigate the impact of initiating early cardiac therapy — such as ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, or novel antifibrotic agents — on long-term morbidity and mortality. Finally, longitudinal studies are essential to explore the natural progression of these imaging biomarkers and their precise relationship with hard clinical endpoints, including arrhythmia, heart failure hospitalization, and sudden cardiac death.

Integrating these insights into multidisciplinary care models could significantly improve cardiac outcomes and overall survival in patients with FA. This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective and cross-sectional design inherently limits the ability to assess longitudinal changes in cardiac function or to establish causal relationships. No standardized clinical or imaging follow-up was available for the included patients, and therefore, the progression of cardiac involvement over time could not be evaluated. This lack of longitudinal data limits our understanding of the temporal evolution of cardiac abnormalities in FA.

Moreover, the study was conducted in a single center with a relatively small number of patients, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, we believe our results provide meaningful insights into the cardiac manifestations of FA and underscore the need for prospective longitudinal studies to better characterize disease progression and outcomes.

In conclusion, our findings support the use of CMR as a noninvasive, comprehensive tool for characterizing the cardiac phenotype in FRDA. The integration of structural, functional, and tissue-based markers enables refined clinical decision-making and may facilitate the development of personalized treatment strategies. Given the prognostic importance of myocardial fibrosis and LV dysfunction, routine CMR screening should be considered in all FRDA patients, particularly during the early stages of neurological disease.