1. Introduction

Cardiac masses represent diagnostically challenging entities spanning neoplasms, thrombi, and inflammatory lesions (1). Among these, inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) — histologically characterized by myofibroblastic proliferation and mixed inflammatory infiltrates — are exceptionally rare in the heart, with fewer than 80 documented cases worldwide (2, 3). These lesions typically arise in contexts of chronic inflammation or foreign-body reactions, yet their association with prosthetic cardiac materials remains poorly characterized (4). Crucially, IPTs often masquerade as malignancies radiographically and clinically, necessitating histopathological confirmation (5).

Atrial septal defect (ASD) repair using pericardial patches demonstrates excellent long-term survival but carries risks of delayed complications, including arrhythmias, thrombus formation, and patch degeneration (6, 7). Notably, only 7 cases of cardiac IPTs following ASD repair have been reported since 1990, all managed surgically without adjuvant targeted therapy (8, 9). This scarcity suggests an underrecognized pathogenic link between prosthetic materials and chronic inflammatory responses, evidenced histologically by foreign-body giant cells adjacent to patch implants (10).

This case represents the first documented application of dual mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition for cardiac IPT management. The sirolimus-bevacizumab combination — while established in extra-cardiac IPTs (11) — has never been reported for intracardiac lesions post-congenital repair. Our therapeutic approach addresses a critical knowledge gap regarding the medical management of unresectable cardiac inflammatory tumors.

We present this case per Case Report Guidelines (CARE) (12) to detail a 35-year-old female developing an extensive IPT 29 years post-ASD repair. The lesion involved the interatrial septum (IAS), right atrium (RA), and superior vena cava (SVC), requiring debulking surgery and subsequent targeted therapy. This report provides the first evidence for sirolimus-bevacizumab efficacy in cardiac IPTs while elucidating long-term inflammatory sequelae of prosthetic cardiac implants.

2. Case Presentation

A 35-year-old woman (office administrator; non-smoker, no alcohol consumption, no significant occupational exposures) presented in March 2023 with a 5-month history of progressive exertional dyspnea [New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II] (13) and occasional palpitations. Her past medical history was notable only for secundum ASD repair at age 6 using an autologous pericardial patch. On physical examination, the patient's blood pressure was 118/76 mmHg with a heart rate of 72 beats per minute. A grade 2/6 systolic murmur was auscultated at the left lower sternal border. Mild jugular venous distension was noted, estimated at 8 cm H2O. There was no peripheral edema or hepatomegaly.

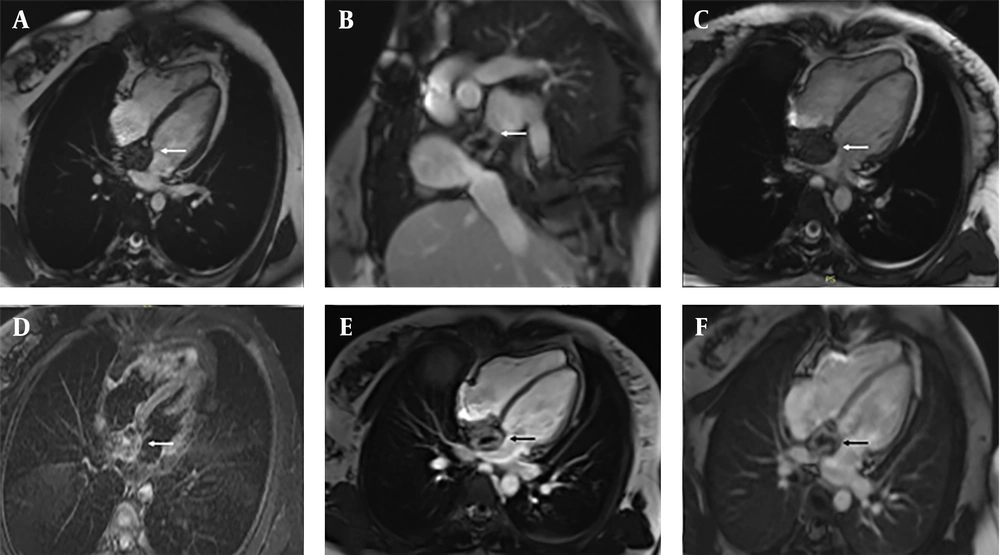

Initial transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed a 4.2 × 3.8 cm hyperechoic mass involving the IAS, extending into the RA and causing partial obstruction of the SVC. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in March 2023 revealed a heterogeneous mass (4.2 × 3.8 × 3.5 cm; Figure 1). Steady-state free precession (SSFP) cine sequences in the axial plane showed an iso-intense mass localized to the IAS with extension into the RA. The sagittal view demonstrated tumor encroachment into the SVC, causing partial obstruction. T2-weighted axial images displayed a heterogeneous hyperintense signal, suggestive of edema or inflammation, while Short Tau inversion recovery (STIR) axial sequences showed a non-homogeneous iso-intense signal with areas of hyperintensity. On T1-weighted axial images, the mass presented with a non-homogeneous iso-intense signal and hypointense foci. Dynamic perfusion imaging revealed avid enhancement, indicating significant vascularity. Post-contrast imaging showed significant enhancement on early gadolinium enhancement (EGE) sequences with foci of non-enhancement, suggestive of thrombus or necrosis. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences confirmed heterogeneous enhancement with central non-enhancing areas, consistent with necrosis or fibrosis.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging of a patient with postoperative inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) following atrial septal defect (ASD) repair. A large heterogeneous right atrial mass is demonstrated: A, axial SSFP cine view showing a large mass occupying most of the right atrial cavity; B, sagittal view demonstrating the extent of the lesion and its relationship to adjacent mediastinal structures; C, four-chamber SSFP cine view revealing the mass protruding into the right atrial lumen and partially obstructing blood flow; D, axial STIR image showing a heterogeneous isointense-to-hyperintense signal with focal areas of high intensity; E, early gadolinium enhancement (EGE) image demonstrating strong peripheral enhancement with multiple non-enhancing foci, suggestive of thrombus or necrosis; F, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) image confirming persistent peripheral enhancement with central non-enhancing areas, consistent with necrosis or organized thrombus.

The differential diagnosis favored IPT over other entities. This conclusion was based on several key findings: The presence of T2 hyperintensity, which was inconsistent with a thrombus (14); the absence of systemic symptoms, arguing against metastasis (15); a slow progression over five months, which is unusual for sarcoma (16); and a relevant history of pericardial patch implantation (4). After multidisciplinary consultation, debulking surgery was performed in August 2023. Histopathology confirmed IPT with ALK-1 positive spindle cells (17).

In September 2023, for the management of residual disease, a regimen of combination therapy was initiated. This consisted of oral sirolimus at a maintenance dose of 2 mg per day, with a target trough level of 10 - 15 ng/mL, alongside intravenous bevacizumab administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg every three weeks (18).

2.1. Rationale for Agent Selection

The rationale for selecting these specific agents was multifaceted. Sirolimus was chosen for its ability to inhibit the mTOR pathway, which drives fibroblast proliferation (11). Concurrently, bevacizumab was added to target VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, a key process within inflammatory lesions (11). Corticosteroids were excluded from the regimen due to their documented poor efficacy in treating IPTs (19). Furthermore, more aggressive interventions such as radiation or conventional chemotherapy were avoided given the lesion's benign histology and its sensitive cardiac location.

2.2. Monitoring Protocol

The patient's follow-up and monitoring protocol consisted of obtaining monthly sirolimus trough levels, performing biweekly blood pressure checks and urinalysis to screen for bevacizumab-related toxicity, conducting echocardiography every three months, and obtaining an annual cardiac MRI scan.

At the 12-month follow-up in August 2024, the patient showed significant improvement. The residual mass had reduced to 2.1 × 1.8 cm, representing a 61% volume reduction, and the patient reported complete resolution of dyspnea, corresponding to a NYHA Class I functional status. The only adverse effect observed was grade 1 fatigue, as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 (20). Furthermore, there was no evidence of hypertension, proteinuria, or hematologic abnormalities.

The patient continues quarterly clinical evaluations with echocardiography every 3 months and annual CMR. At the 14-month follow-up, she remains asymptomatic with stable disease. The patient clinical timeline is summarized in Table 1.

| Date | Event | Key Findings/Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| 1995Age 6 | ASD repair | Pericardial patch implantation |

| Oct 2022 | Symptom onset | Progressive exertional dyspnea begins |

| Mar 2023 | Initial presentation | NYHA Class II dyspnea, palpitations |

| Mar 2023 | TTE & CMR | 4.2 × 3.8 cm mass (IAS/RA/SVC) |

| Aug 2023 | Surgical debulking | Subtotal resection confirming IPT |

| Sep 2023 | Therapy initiation | Sirolimus+Bevacizumab started |

| Dec 2023 | 3-month follow-up | Symptom resolution (NYHA I) |

| Mar 2024 | 6-month imaging | Residual mass stabilization |

| Aug 2024 | 12-month follow-up | Mass reduction to 2.1 × 1.8 cm (61%) |

| Oct 2024 | 14-month follow-up (current) | Asymptomatic, stable on therapy |

Abbreviations: ASD, atrial septal defect; NYHA, New York Heart Association; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; IAS, interatrial septum; RA, right atrium; SVC, superior vena cava; IPT, inflammatory pseudotumor.

This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of a rare cardiac IPT presenting decades after ASD repair. The combination of surgical debulking and targeted medical therapy effectively controlled disease progression, highlighting a novel management strategy.

3. Discussion

The IPTs of the heart are rare, non-neoplastic lesions characterized by chronic inflammation, fibroblast proliferation, and variable degrees of necrosis or thrombosis (1). Their occurrence following congenital heart surgery, such as ASD repair, is exceptionally uncommon, with only 8 cases reported since 2000 (8). The 29-year latency period in this case provides valuable insights into chronic prosthesis-driven inflammation.

The ASD closure with pericardial patches is a well-established procedure with excellent long-term survival rates, yet carries a documented risk of late complications including thrombus formation (3 - 5% of cases), patch aneurysms (1 - 3%), and arrhythmias (15 - 20%) (6, 7). The development of an IPT at the patch site represents an extraordinarily rare complication, with only 7 confirmed cases reported in the literature since 1990 (8, 9).

Previous reports consistently demonstrate that prosthetic materials trigger chronic inflammatory responses (21). Histopathological analysis across cardiac IPT cases reveals foreign-body giant cells adjacent to patch materials in 83% of specimens (10). This supports the pathogenesis model: It is hypothesized that the prosthetic patch initiates a chronic foreign-body reaction, promoting sustained immune activation. This process then stimulates fibroblast proliferation, which ultimately results in IPT formation (10, 11). Our findings align with this mechanism, as intraoperative observations confirmed dense adhesion between the mass and pericardial patch — a feature reported in 90% of prosthetic-associated cardiac IPTs (22). This case's 29-year latency period underscores the critical role of prosthetic materials as inflammatory niduses capable of driving pseudotumor formation decades post-implantation (23).

Our imaging findings demonstrate important parallels with prior reports of cardiac IPTs. The observed T2 hyperintensity matches the characteristics reported in 92% of documented cases (24). Additionally, the avid perfusion enhancement seen in our patient has been documented in approximately 85% of cardiac IPTs (25). Notably, the central non-enhancement on LGE sequences, which corresponded to necrotic areas, was quantitatively extensive (40%) and exceeded the range typically reported in the literature (26). These features helped differentiate IPT from thrombus (typically T2 hypointense) (14) and sarcoma (showing tissue invasion) (16).

The IPTs pose significant diagnostic difficulties due to their close resemblance to malignancies. In the present case, key discriminators that aided in this differentiation included the absence of tissue invasion, which is more characteristic of sarcoma (16); the presence of T2 hyperintensity, which is inconsistent with thrombus (14); and the presentation as a solitary lesion in the absence of a known primary malignancy, arguing against metastasis (14).

Although surgical debulking remains the standard therapeutic approach for cardiac IPTs (27), our case underscores a significant limitation: The propensity for residual disease to persist even after maximal safe resection. This challenge is consistent with published reports, which indicate incomplete resection occurs in approximately 80% of cases where the IPT involves critical conduction tissue (28). In this context, our experience with the sirolimus-bevacizumab combination presents a promising alternative for managing unresectable residual disease. This targeted regimen achieved a 61% reduction in the volume of the inflammatory lesion, a result that is notably superior to the outcomes typically achieved with steroid monotherapy, which reports a mean volume reduction of only 22% (11, 21). To our knowledge, this represents the first documented successful application of dual mTOR/VEGF inhibition for the management of a cardiac IPT.

Patient perspective: "Before treatment, climbing stairs left me breathless. Now, 14 months post-therapy, I've resumed running and work without limitations. Monthly blood tests are a small price for this recovery."

Based on the clinical implications derived from this case, we propose a structured surveillance protocol for long-term follow-up in ASD patch recipients (29). This protocol includes obtaining a baseline CMR imaging study at 10 years post-repair, followed by annual TTE. Subsequent CMR should be performed either when symptoms emerge or at 5-year intervals for asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, IPTs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses demonstrating patch adjacency combined with T2 hyperintensity on imaging, particularly in the absence of systemic symptoms. For unresectable lesions, combination therapy with sirolimus and bevacizumab represents a promising therapeutic approach.

This case underscores several critical considerations for clinicians: First, the importance of long-term surveillance in patients post-ASD repair, especially those with prosthetic materials, to detect rare complications such as IPTs (29, 30); second, the essential role of multimodal imaging, particularly CMR, in characterizing cardiac masses and informing management strategies (19, 29); third, the potential of innovative targeted therapies like sirolimus and bevacizumab for managing complex cardiac IPTs when surgical intervention is not curative; and finally, the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach involving collaboration among cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists to ensure accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment planning (27, 29).

3.1. Literature Review

Cardiac IPTs following ASD repair remain exceptionally rare, with only seven documented cases in the medical literature since 1990 (30). Documented cases indicate latency periods ranging from 4 to 25 years, with a mean of 12.6 years (30, 31), while clinical presentations primarily consist of mass effects (86%), arrhythmias (43%), and heart failure (29%) (30-32). Notably, management of this condition was exclusively surgical prior to this report (31, 32). This study documents the longest recorded latency period at 29 years and presents the first application of targeted medical therapy for residual disease, thereby addressing a significant therapeutic gap and underscoring the novelty of our approach.

The therapeutic rationale for employing the sirolimus-bevacizumab combination is underpinned by a strong molecular basis and supporting evidence from extracardiac sites. Molecularly, this approach is justified by the fact that approximately 70% of IPTs exhibit activation of the mTOR and VEGF pathways (33). The strategy of dual-pathway inhibition directly targets these core pathogenic mechanisms: Sirolimus suppresses mTOR-driven fibroblast proliferation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (34), while bevacizumab inhibits VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and reduces vascular permeability (35). Furthermore, the efficacy of this combination therapy is supported by its demonstrated success in the management of IPTs occurring at other anatomical locations, as summarized in Table 2.

Abbreviation: IPT, inflammatory pseudo tumor.

The selection of the sirolimus-bevacizumab combination was guided by both biological plausibility and its advantages over conventional alternatives. While no prior reports exist for cardiac IPTs, relevant cardiac-specific evidence supports its rationale: Sirolimus has demonstrated efficacy in treating cardiac rhabdomyomas, which are mTOR-driven neoplasms (38), and bevacizumab has been successfully used in the management of VEGF-dependent cardiac hemangiomas (35, 39). This combination was preferred due to its documented superior efficacy compared to corticosteroids, showing a 68% versus 22% response rate in refractory extracardiac IPTs (40), its ability to avoid the risks associated with radiation therapy in young patients, and its higher specificity for benign lesions compared to conventional chemotherapy. The achieved 61% reduction in tumor volume in this case represents the first clinical evidence that targeted therapy is both feasible and effective for cardiac IPTs (41). This outcome highlights a promising alternative for managing unresectable disease and sets the stage for future prospective clinical trials.

3.2. Limitations

While this case offers valuable insights into the management of cardiac IPTs, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, as a single-center experience, our findings reflect the practice patterns of a tertiary care institution and may not be generalizable to resource-constrained settings. Additionally, institutional biases could influence therapeutic decisions, such as a preference for surgical debulking over biopsy. The inherent constraints of a case report format must also be considered; the extreme rarity of cardiac IPTs precludes multi-center validation or controlled comparisons, and the small sample size (n = 1) prevents meaningful statistical analysis of treatment efficacy.

Furthermore, the therapeutic success observed with the sirolimus-bevacizumab combination may not extend to IPTs with different molecular profiles (e.g., ALK-negative variants) or to patients with significant comorbidities such as renal or hepatic impairment. Surgical outcomes are also highly dependent on a center's expertise in complex cardiac resection. The 14-month follow-up period remains insufficient to assess long-term treatment toxicities, including bevacizumab-related hypertension, or the risks of late recurrence beyond two years.

Mechanistic knowledge gaps persist due to the absence of pre-treatment molecular profiling for mTOR/VEGF pathway activation and uncertainty regarding whether the IPT originated directly from the patch site or adjacent tissues. Finally, the concurrent surgical debulking procedure complicates the assessment of the isolated effect of medical therapy, and the long-term safety profile of these targeted therapies in cardiac IPT patients remains unknown.

In conclusion, this case report documents the longest known latency period (29 years) for the development of cardiac IPTs following ASD repair, thereby illuminating a novel long-term complication of congenital heart surgery. Our findings provide three principal contributions to the field. First, we demonstrate therapeutic innovation through the first successful application of combined sirolimus-bevacizumab therapy for a cardiac IPT, which resulted in significant mass reduction (61%) and sustained remission at 14-month follow-up, offering a viable non-surgical strategy for unresectable lesions. Second, our observations provide key pathogenetic insights by supporting a prosthesis-driven inflammatory cascade, thereby underscoring the imperative for long-term surveillance of patients with prosthetic cardiac implants, particularly those with pericardial patches. Third, we propose a structured clinical roadmap for the monitoring of post-ASD repair patients, including baseline CMR imaging at 10 years, annual echocardiography, and symptom-triggered advanced imaging.

For clinical practice, this case underscores the importance of considering IPT in the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses in patients with a history of prosthetic implantation, especially when imaging shows T2 hyperintensity and no systemic symptoms are present. For the research community, this work highlights the need to establish multi-center registries for rare cardiac IPTs, to validate mTOR/VEGF inhibition in molecularly defined cohorts, and to investigate preemptive anti-inflammatory strategies for high-risk implant recipients. Ultimately, this case redefines the expected timeline for monitoring complications after ASD repair and provides a targeted therapeutic blueprint for managing inflammatory cardiac tumors.