1. Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally transforming radiology by enhancing diagnostic accuracy, image processing, and workflow efficiency (1, 2). Radiologists increasingly rely on AI tools such as deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and computer-aided detection (CAD) systems to manage growing workloads and maintain quality standards amid escalating global imaging demand (1, 3). Systematic reviews across breast, neuro, thoracic, and ophthalmic imaging show aggregated area under the curve (AUC) values often exceeding 0.9 compared with human readers (4-6).

The AI applications in radiology span lesion detection, dose reduction, clinical decision support, and report automation (1, 7). However, concerns over algorithmic bias, generalizability, data privacy, and ethical transparency persist — particularly in systems trained on skewed datasets or lacking explainability features (8, 9). Trainees and early-career professionals frequently report anxiety regarding AI’s role, compounded by the perceived insufficiency of formal training and curricular exposure (4, 10).

Globally, AI adoption in radiology is uneven. High-income countries benefit from robust digital infrastructure and legal frameworks supporting integration, while low- and middle-income regions face barriers including equipment shortages, lack of expert training, data rights ambiguity, and system interoperability challenges (11, 12).

In the Turkish context, AI is gradually entering clinical radiology amid centralized training systems, institutional disparities, and limited radiology-specific AI education (7, 10). While evidence from Western settings is extensive, researchers have called for localized surveys to better understand Turkish radiologists’ perceptions and readiness for AI integration. To ensure AI adoption is safe, equitable, and contextually sensitive, it is essential to explore radiologists’ experiences, expectations, and concerns in Turkey. Insight into their current level of engagement and trust in AI tools will guide the design of effective training programs, inform policy development, and facilitate the responsible scaling of AI support in national radiology practice.

2. Objectives

The rapid emergence of AI in radiology has generated substantial interest among clinicians, educators, and policymakers. However, most existing research on radiologists’ attitudes toward AI has been conducted in high-income, Western contexts, leaving a gap in our understanding of how AI is perceived and utilized in countries with differing healthcare infrastructures, such as Turkey. Despite global enthusiasm for AI’s potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and clinical decision-making, significant disparities in infrastructure, training, and regulatory support may shape national experiences and perceptions in unique ways.

In this context, the present study aims to comprehensively assess the experience, current usage, and expectations surrounding AI among radiologists in Turkey. Specifically, the objectives of this study are:

1. To evaluate the frequency and context of AI tool usage among practicing Turkish radiologists, including both interpretive and non-interpretive applications such as image analysis, automated reporting, and workflow triage.

2. To explore radiologists' perceptions regarding the opportunities and challenges posed by AI, including its potential to improve clinical outcomes, streamline radiological services, and support diagnostic confidence.

3. To investigate prevailing attitudes toward the ethical, legal, and professional implications of AI adoption, such as concerns related to data privacy, algorithmic transparency, and potential disruptions to professional roles.

4. To identify the level of preparedness and perceived training needs related to AI, particularly in terms of access to structured education, mentorship, and institutional support for AI integration.

5. To examine the degree to which radiologists in Turkey express concern about AI-driven job displacement, and whether these concerns differ by demographic or professional characteristics such as age, years of experience, or type of institution.

We hypothesize that while actual usage of AI tools among Turkish radiologists remains relatively limited, there is a generally positive outlook regarding the future integration of AI into clinical workflows. Furthermore, we anticipate that most radiologists do not currently perceive AI as an imminent threat to job security but instead express a desire for structured training and ethical safeguards to ensure that AI becomes a complementary tool rather than a disruptive force in clinical practice.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Design

In the present study, the prevalence of AI tool usage and future perspectives of radiologists in Turkey on AI in radiology were investigated using a cross-sectional, descriptive survey design. Pre-specified primary outcomes were (1) prior AI use (yes/no) and (2) perceived usefulness and perceived reliability of AI among prior users. Pre-specified primary associations included: The AI knowledge with willingness to integrate AI; AI knowledge with prior AI use; and formal AI training with perceived reliability/usefulness (among users). Secondary analyses explored additional cross-tabulations of demographics with perceptions. All other analyses were considered exploratory.

3.2. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Izmir City Hospital on December 4, 2024 (decision No.: 2024/233).

3.3. Participants

Participants included practicing radiologists across Turkey, representing a wide range of professional titles: Assistant doctors (residents), specialist doctors, assistant professors, associate professors, and professors. Radiologists were recruited from various healthcare institutions, including university hospitals, state hospitals, private hospitals, and dedicated imaging centers. Eligibility criteria required participants to be currently practicing radiology in Turkey at the time of the survey.

3.4. Survey Development

A structured questionnaire was developed specifically for this study after a review of the literature on AI adoption and perceptions among healthcare professionals. The survey consisted of 36 items across six domains: Demographics, knowledge/training, AI tool use, perceptions, expectations, and legal/ethical views. Skip logic was applied, so certain items (e.g., questions on AI reliability and confidence) were only displayed to respondents who had reported prior AI use.

The questionnaire was composed of multiple sections, assessing:

- Demographic information: Title, workplace, and years of professional experience.

- Knowledge and training: Self-assessment of AI knowledge level (none, basic, intermediate, advanced) and experience with formal AI training programs. Basic knowledge was defined as awareness of general AI concepts; intermediate as familiarity with specific applications in radiology; advanced as the ability to critically appraise or implement AI tools.

- Experience with AI tools: Prior use of AI tools in clinical practice or research, types of features used (e.g., lesion detection, auxiliary interpretation), and encountered integration challenges. The AI tools were defined for respondents as software for lesion detection, automated measurements, image post-processing, prioritization, or workflow triage.

- Perceptions of AI: Views on the usefulness and reliability of AI tools, effect on workload, and confidence in reporting.

- Future expectations: Attitudes towards AI's potential future impact on radiology, willingness to integrate AI into clinical practice, and concerns about AI replacing radiologists.

- Legal and ethical considerations: Views on responsibility for errors caused by AI systems and patient data protection practices.

The full questionnaire is provided in the Appendix in Supplementary File.

3.5. Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed electronically via professional radiology associations, hospital groups, and social media platforms frequently used by Turkish radiologists:

- Turkish Society of Radiology mailing list.

- Some hospitals’ WhatsApp radiology group chats (not all hospitals).

- Some general radiology group chats on WhatsApp.

This was a convenience sample; we did not attempt to reach all radiologists in Turkey but rather recruited those accessible through national radiology associations, hospital groups, and widely used social media channels. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and without compensation. Eligibility was restricted to radiologists currently practicing in Turkey at the time of the survey. Respondents were informed about the aim of the study, and consent was implied by voluntary completion of the survey. Invitations were not unique; overlap between distribution channels was possible. Therefore, a precise denominator and formal response rate could not be calculated. The survey was available between the 15th of January 2025 and the 15th of March 2025, with two reminders.

3.6. Variables Measured

Independent variables included participants' demographic characteristics (title, workplace, years of experience) and self-reported level of AI knowledge. Dependent variables included:

- Previous use of AI tools (yes/no).

- Type and features of AI tools used.

- Perceived usefulness and reliability of AI tools.

- Expectations regarding AI’s impact on workload and diagnostic accuracy.

- Concerns about AI-driven job displacement.

- Opinions on legal responsibility for AI-related errors.

3.7. Instrument Development and Validation

The questionnaire was developed after reviewing relevant literature on AI adoption in radiology. Content validity was established through expert review by a panel consisting of two European Board-certified radiologists, one associate professor of radiology, and one researcher with expertise in AI applications. All items were reviewed in two iterative rounds, and feedback was incorporated to refine clarity, wording, and relevance. Content validity was supported by expert panel review; formal Item- and Scale-Level Content Validity indices (I-CVI/S-CVI) were not computed. A cognitive pre-test was not performed due to time constraints.

To minimize respondent burden and maximize completion rates, the survey primarily relied on single-item measures rather than multi-item scales. As a result, Internal Consistency indices (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) or exploratory factor analysis were not applicable. No separate cognitive pre-test was conducted due to time constraints; however, clarity and comprehensibility were ensured through the expert panel review process.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to summarize the characteristics of the participants and survey responses. Chi-square tests were used to explore associations between key variables, including:

- The AI knowledge level and perceived usefulness of AI tools.

- Years of radiology experience and AI knowledge.

- Perceived reliability of AI tools and perceived usefulness.

For chi-square tests, we report Cramer’s V as an effect size; for ordinal by ordinal associations, we report Goodman-Kruskal’s gamma (γ). Descriptive statistics were presented as counts and percentages. Associations between ordinal variables were examined using Spearman’s rho, and chi-square tests were applied for categorical comparisons. All P-values are reported as two-sided, with values < 0.001 expressed as such. Analyses of perceived reliability and usefulness were restricted to respondents who reported prior AI use; corresponding analytic sample sizes are shown in table titles/footnotes (e.g., “among AI users, n = 93”). All tests were exploratory, and P-values are unadjusted. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results

A total of 244 radiologists participated in the survey. Missing data were minimal and were handled by complete-case analysis, with denominators reported in the tables. According to national statistics, Turkey has approximately 4,000 practicing radiologists. Our sample of 244 represents about 6% of the national workforce. University/academic hospital radiologists were somewhat overrepresented compared with the national distribution, possibly inflating AI familiarity.

4.1. Participant Characteristics

Specialist doctors represented the largest group (45.5%), followed equally by assistant doctors (residents) and associate professors (both 17.6%). Professors constituted 12.7%, while assistant members/assistant associate professors were the smallest group at 6.6%. Nearly half (48.4%) worked at education and research hospitals (ERHs)/city hospitals/university-affiliated institutions, followed by university hospitals (18.4%) and private hospitals (13.1%). Smaller proportions were employed at state hospitals (11.1%) and dedicated imaging centers (7.4%). Years of experience showed a fairly balanced distribution with a slight emphasis on mid-career professionals: 41.4% had 11 - 20 years of experience, 38.5% had 1 - 10 years, and 20.1% had 21 or more years of experience (Table 1).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Professional title | |

| Assistant doctors (residents) | 43 (17.6) |

| Specialist doctors | 111 (45.5) |

| Associate professors | 43 (17.6) |

| Professors | 31 (12.7) |

| Assist. members/Assist. Assoc. Prof. | 16 (6.6) |

| Institution type | |

| ERH/city/university-affiliated | 118 (48.4) |

| University hospitals | 45 (18.4) |

| Private hospitals | 32 (13.1) |

| State hospitals | 27 (11.1) |

| Imaging centers | 18 (7.4) |

| Years of experience | |

| 1 - 10 | 94 (38.5) |

| 11 - 20 | 101 (41.4) |

| ≥ 21 | 49 (20.1) |

Abbreviations: Assist. Assoc. Prof., assistant associate professor; ERH, education and research hospital.

4.2. Artificial Intelligence Knowledge, Training, and Use

Most participants rated their AI knowledge as basic (59.8%), while 23.8% reported intermediate knowledge. A minority had advanced knowledge (2.9%), and 13.5% reported no knowledge of AI. Formal AI training was lacking for the majority (72.1%), with only 27.9% having received structured education, such as hospital-based courses, congresses, or private training. Experience with AI tools was limited; 61.9% (151/244) had never used AI tools, whereas 38.1% (93/244) reported prior use (68 clinical, 25 research-only). Among these users, 73 reported that AI tools increased their confidence in radiological reports, 18 were uncertain, and 2 felt no confidence increase. Perceived reliability was mixed: Eighty-four considered AI reliable, 5 unreliable, and 4 very reliable. Usefulness ratings were generally positive: Seventy-eight found AI helpful, 10 very useful, 4 useless, and 1 not useful at all (Table 2).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| AI tool use | |

| Clinical use | 68 (27.9) |

| Research-only use | 25 (10.2) |

| Never used | 151 (61.9) |

| Formal AI training | |

| Yes | 68 (27.9) |

| No | 176 (72.1) |

| Self-rated AI knowledge | |

| None | 33 (13.5) |

| Basic | 146 (59.8) |

| Intermediate | 58 (23.8) |

| Advanced | 7 (2.9) |

Abbreviation: AI, artificial intelligence.

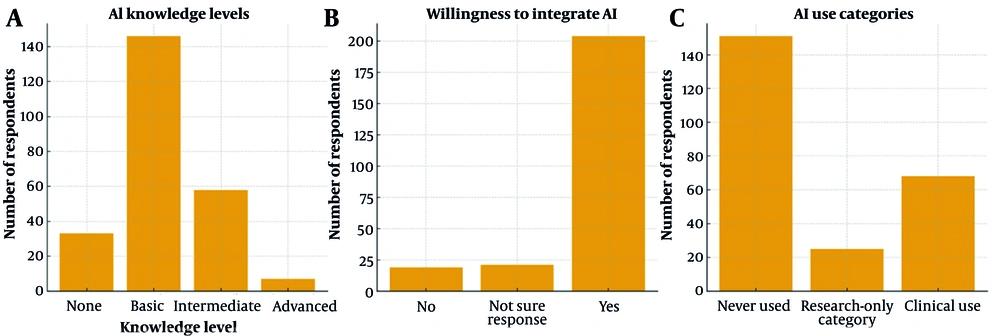

Key distributions are summarized in a single multi-panel figure, showing AI knowledge levels, willingness to integrate AI, and AI use categories (Figure 1).

Distribution of key survey variables among radiologists (n = 244); A, Self-reported artificial intelligence (AI) knowledge levels: The majority reported basic knowledge, followed by intermediate, none, and advanced; B, Willingness to integrate AI into daily workflow: Most participants expressed interest, while smaller proportions were uncertain or uninterested; C, AI use categories: 61.9% had never used AI, while 27.9% reported clinical use and 10.2% research-only use.

4.3. Associations Between Knowledge, Training, and Perceptions

Higher AI knowledge was strongly associated with willingness to integrate AI into daily workflow (ρ = 0.64, P < 0.001). Knowledge level was also moderately associated with clinical AI use (ρ = 0.42, P = 0.001). Among AI users, formal training was weakly correlated with the perceived reliability of AI tools (ρ = 0.175, P = 0.006). Diagnostic benefit was positively correlated with reliability ratings (ρ = 0.241, P < 0.001). Years of experience showed no significant association with diagnostic benefit (ρ = 0.040, P = 0.053). Radiologists anticipating major changes in the next decade were significantly more likely to consider AI promising for diagnostic accuracy (χ2 = 124.3, P < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.50; Table 3, Appendices 4 - 11 in Supplementary File).

| Outcome/predictor | ρ (spearman)/χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Willingness to integrate AI vs. AI knowledge | ρ = 0.64 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical AI use vs. AI knowledge | ρ = 0.42 | 0.001 |

| Reliability vs. formal AI training (AI users) | ρ = 0.175 | 0.006 |

| Diagnostic benefit vs. reliability (AI users) | ρ = 0.241 | < 0.001 |

| Experience vs. diagnostic benefit | ρ = 0.040 | 0.053 |

| Anticipated change vs. diagnostic accuracy | χ2 = 124.3; Cramer’s V = 0.50 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: AI, artificial intelligence.

a Percentages and denominators are indicated in each table.

b Analyses involving reliability and usefulness are restricted to AI users.

4.4. Discrepancies Between Artificial Intelligence and Radiologist Interpretations

Among 93 radiologists who reported prior AI use, 41 reported at least one discrepancy, while 44 reported none, and the rest did not know if there was any. In discrepant cases, the radiologist’s interpretation was considered valid in 37 cases (90.2%), while AI alone, equal validity, or alternating judgments were each chosen by one respondent (2.4% each). Results are reported descriptively due to small cell counts (Appendix 6 in Supplementary File).

5. Discussion

This national survey indicates that Turkish radiologists generally express positive attitudes toward AI, although actual clinical use and knowledge remain limited. Only 38.1% reported ever using AI tools, and the majority rated their knowledge as basic. A strong positive association was observed between knowledge level and willingness to integrate AI into daily workflow, suggesting that structured education is a key determinant of adoption.

Our results are comparable with findings from Huisman et al., who reported high optimism but relatively limited experience with AI among European radiologists (4). Similarly, Ranschaert et al. highlighted that the optimization of radiology workflow with AI requires not only technological readiness but also formal training and governance structures, which are still insufficient in Turkey (7). In addition, Khan et al. described barriers to AI implementation in low- and middle-income countries, including infrastructure limitations and lack of regulatory clarity, factors that may also contribute to the relatively modest adoption observed in our study despite the positive expectations (12).

This study has several limitations. The use of electronic distribution channels may have led to selection bias, with radiologists more familiar with digital tools potentially overrepresented. Academic radiologists were relatively more represented compared with non-academic colleagues, possibly inflating AI familiarity. The cross-sectional design precludes temporal analysis of changing attitudes, and age or gender-related effects were not evaluated. Selection bias is possible because recruitment occurred primarily via electronic media (mailing lists and WhatsApp groups). We did not collect age, and younger radiologists may use electronic channels more frequently and be more familiar with AI. If younger radiologists were overrepresented, AI familiarity could be overestimated in our sample. This risk of selection bias should be considered when interpreting our results. In addition, the questionnaire did not include an item on AI-assisted report generation, which represents a limitation and should be addressed in future surveys. The questionnaire relied primarily on single-item measures; no multi-item subscales were included, so internal consistency and factor analyses were not applicable. Because regional data were not collected, we could not evaluate geographic representativeness; this may limit generalizability across Turkey’s regions. We did not compute the I-CVI or the S-CVI and did not conduct a cognitive pre-test; both are acknowledged limitations that may affect item clarity and content validity. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting representativeness.

Based on the findings, several recommendations can be made. National training programs should be developed to transform general awareness into practical competence at different career stages. Institutional support is needed to overcome integration difficulties, including information technology (IT) infrastructure and local validation of AI systems. Finally, policymakers should provide clear guidelines on accountability and data protection to support safe and trusted implementation.

In conclusion, Turkish radiologists are optimistic about the role of AI but have limited practical experience. Addressing training, infrastructure, and regulatory gaps will be essential to enable effective and reliable integration of AI into radiological practice in Turkey.