1. Background

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive technique that provides high-resolution anatomical and functional images with excellent soft and hard tissue contrast without using ionizing radiation (1). In dentistry, it is used for evaluating temporomandibular joint disorders, oral and maxillofacial tumors, salivary gland pathologies, vascular lesions, and early-stage osteomyelitis. However, its application remains limited, primarily due to restricted access for dental practitioners and image artifacts caused by metallic dental materials (2, 3).

One of the primary challenges in the clinical application of MRI in the head and neck region is the presence of artifacts caused by metallic materials, particularly dental implants, within the magnetic field. These artifacts arise from magnetic susceptibility differences between the implant material and surrounding tissue, leading to signal voids, distortions, and geometric deformations in MRI scans. Among these, signal loss due to dephasing is the most common artifact observed near metallic objects (4-6).

The severity and extent of metal-induced artifacts depend not only on the physical properties of the metallic material but also significantly on the imaging parameters selected. For instance, spin echo (SE) techniques, which utilize a 180-degree refocusing pulse, generally produce fewer artifacts compared to gradient echo (GRE) sequences that lack this compensatory pulse. Various MRI sequences are employed to enhance the contrast of target tissues during diagnosis, each consisting of different combinations of radiofrequency pulses and gradient manipulations (6).

Imaging conditions substantially influence the degree of artifact formation, with the choice of sequence being one of the most critical factors. Metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS) broadly refer to MRI protocols specifically optimized for imaging in the presence of metal. Over the last few decades, various sequences have been introduced to obtain ideal images with fewer metal artifacts. The MARS was described by Olsen in 2000. More advanced sequences for metal artifact reduction have been introduced, including view angle tilting (VAT), slice encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC), and multi-acquisition variable-resonance image combination (MAVRIC). Although these methods have been primarily developed for orthopedic and neurosurgical applications, their use in head and neck imaging remains limited. Moreover, the results of previous studies are not readily generalizable to the head and neck region, given the differences in type, shape, and quantity of metallic materials compared to orthopedic or neurosurgical implants, which in turn affect the extent and pattern of artifacts (7-10).

Prior research on artifacts from dental materials has predominantly focused on orthodontic appliances, with stainless steel brackets identified as the most common source of MRI artifacts in the head and neck (11). Conversely, data regarding dental implants are scarce, and most investigations have been conducted in non-bony environments using conventional MRI sequences.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aims to investigate artifacts induced by various dental implant materials across multiple MRI sequences, comparing conditions with and without the application of MARS in anterior and posterior regions of the jaws, using a dry human skull model that simulates realistic clinical conditions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Selection

This descriptive in vitro study included five samples of each implant type, a number determined based on the mean and standard deviation (SD) of artifact volumes reported by Bohner et al. (12).

3.2. Dental Implants and Specimen Preparation

Three types of dental implants were evaluated: Titanium (Ti), zirconia (Zr), and titanium-zirconium (Ti-Zr) alloy, all standardized in size (8 mm length × 3.3 mm diameter, Table 1).

| Implant types | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Manufacturer | Material composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | 8 | 3.3 | Institut Straumann AG | Grade 4 Ti: Ti, O ≤ 0.4%, Fe 0.25 - 0.5%, N ≤ 0.05%, C ≤ 0.10%, H ≤ 0.012% |

| Ti-Zr | 8 | 3.3 | Institut Straumann AG | Eighty-five percent grade 4 Ti and 15% zirconium: Ti 85%, O ≤ 0.24%, Fe ≤ 0.05%, N ≤ 0.02%, C ≤ 0.05%, H ≤ 0.005%, Zr 15% |

| Zr | 8 | 3.3 | Institut Straumann AG | Pure ceramic: Y-TZP, ZrO2 + HfO2 + Y2O3 ≥ 99%, Y2O3 4.5 - 6%, HfO2 ≤ 5%, residuals ≤ 1% |

Abbreviations: Ti, titanium; Ti-Zr, titanium-zirconium; Zr, zirconium; Y-TZP, yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia.

Each implant was individually placed within the maxillary alveolar socket of a dry human skull. For each material, implants were positioned twice: Once in the anterior maxillary region (upper left second incisor) and once in the posterior maxillary region (upper left second molar). Agar gel was used to stabilize the implants.

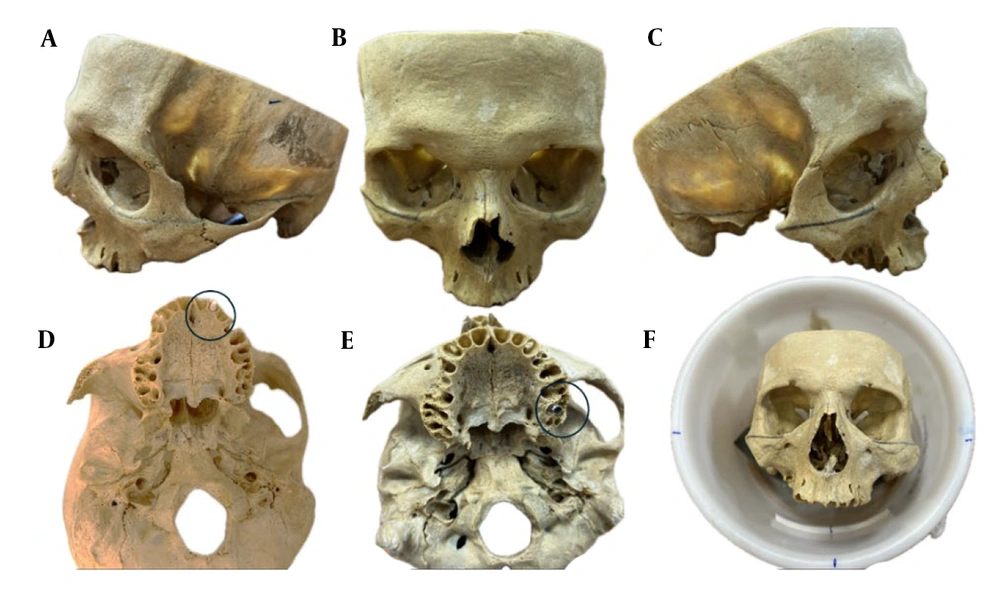

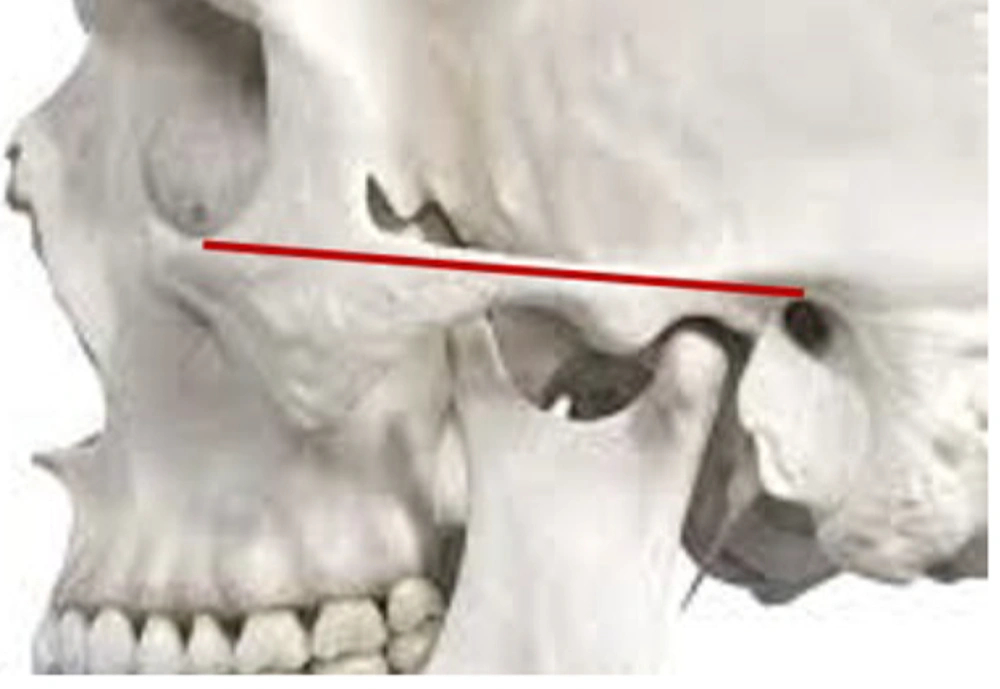

To simulate soft tissue and improve imaging contrast, the skull was placed in a cylindrical container filled with water, approximating the average human head diameter (1). The Frankfort horizontal plane, defined as the line connecting the inferior orbital rim to the superior margin of the external auditory canal, was oriented perpendicular to the horizontal axis to mimic natural head positioning during MRI scanning (Figures 1 and 2).

Lateral (A and C) and frontal (B) views of the dry human skull with the Frankfort plane marked; axial views showing the anterior (D) and posterior (E) implant placement sites marked with circles. The skull positioned within a water-filled cylinder ensuring the Frankfort plane is perpendicular to the horizontal (F).

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Acquisition

Imaging was performed using a 1.5 Tesla Ingenia Ambition MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) at Shahid Rajaee Educational Department. An 8-channel head coil was employed, and the specimen was stabilized with positioning pads before being placed at the magnet’s isocenter. For each implant material and position (anterior and posterior), the imaging protocol was repeated five times using different implants of the same type. Ten MRI sequences were acquired for each placement (Table 2), including:

- T1-weighted (T1W) and T1W with MARS (T1W+MARS)

- T2-weighted (T2W) and T2W+MARS

- Proton density-weighted (PDW) and PDW+MARS

- Three-dimensional (3D) T1W and 3D T1W+MARS

- The 3D T2W and 3D T2W+MARS

| Sequences | Slice thickness (mm) | Bandwidth (Hz) | NEX | Pixel size (mm) | FOV (mm) | Time (min) | TR/TE (ms) |

| T1W TSE | 2 | 464 | 6 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.32 | 610/15 |

| T2W TSE | 2 | 460 | 6 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.26 | 3838/80 |

| PDW TSE | 2 | 446 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.00 | 1500/28 |

| 3D T1W | 0.5 | 367 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 5.00 | 2500/80 |

| 3D T2W | 0.5 | 367 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 5.00 | 3000/260 |

| T1W TSE+MARS | 2 | 847 | 6 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.32 | 601/15 |

| T2W TSE+MARS | 2 | 944 | 6 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.26 | 3838/80 |

| PDW TSE+MARS | 2 | 858 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 2.00 | 1500/28 |

| 3D T1W+MARS | 0.5 | 840 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 5.00 | 2500/80 |

| 3D T2W+MARS | 0.5 | 840 | 2 | 1 × 1 × 1 | 140 × 140 | 5.00 | 3000/260 |

Abbreviations: NEX, number of excitations; FOV, field of view; T1W, T1-weighted; T2W, T2-weighted; TSE, turbo spin echo; PDW, proton density-weighted; 3D, 3-dimensional; MARS, metal artifact reduction sequence.

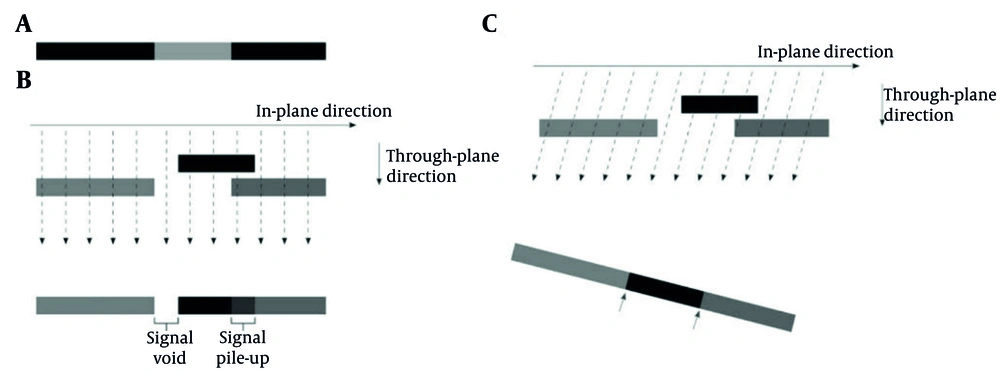

The MARS technique incorporated VAT, which modifies the view angle in the phase-encoding direction to reduce metal-induced distortions, as illustrated in Figure 3 (13).

Schematic representation of the view angle tilting (VAT) technique: A, Homogeneous magnetic field; B, Distorted field without VAT correction; and C, Distorted field with VAT correction. In panel (B), field distortions result in signal voids and signal pile-up in the imaging slice, caused by magnetic field inhomogeneities. In panel (C), applying a readout-direction tilt (VAT) reduces these distortions; however, this comes at the cost of edge blurring and decreased boundary sharpness, indicated by the black arrows.

3.4. Image Analysis and Artifact Quantification

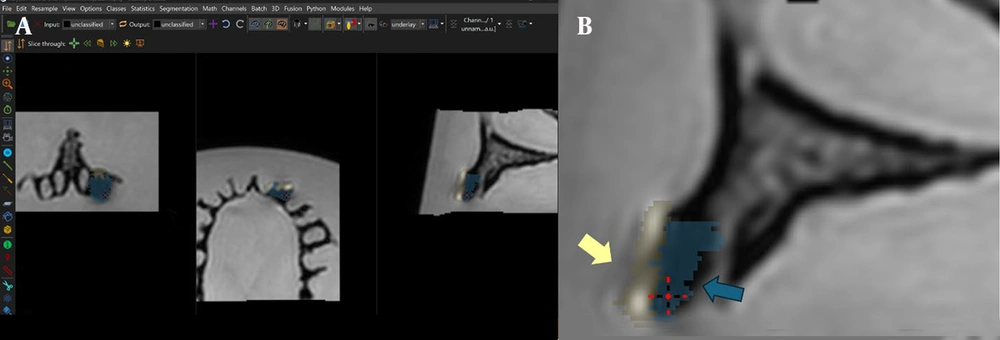

The MRI datasets in DICOM format were imported into Imalytics Preclinical software (Gremse-IT GmbH, Aachen, Germany) (6) for quantitative analysis. An oral and maxillofacial radiologist, trained by a general radiologist and an MRI physicist in artifact recognition and classification, performed all image interpretations. Each measurement was repeated three times at two-week intervals, resulting in an excellent intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC).

All analyses were conducted with the observer blinded to implant material and MRI sequence. Fixed thresholds were applied for both artifact types, and window/level settings (brightness and contrast) were kept constant across all images. To minimize partial-volume effects, boundary voxels at implant margins were excluded from artifact volume calculations. Two artifact types were defined within the software: Signal loss and pile-up artifacts, each assigned a unique color. Signal loss artifacts appeared as dark, signal void regions surrounding the implant, whereas pile-up artifacts were bright regions, often near implant edges, caused by improper image reconstruction, leading to misleading high-intensity signals (14).

Artifact volumes were measured in all three imaging planes (axial, coronal, sagittal) to ensure comprehensive coverage (Figure 4).

Imalytics software environment used for artifact quantification: A, Software interface showing artifact classification in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes; and B, Zoomed-in view of the classified regions, with pile-up indicated by yellow arrows and signal loss indicated by blue arrows. The ‘Statistics’ tab displays corresponding artifact volumes (mm3).

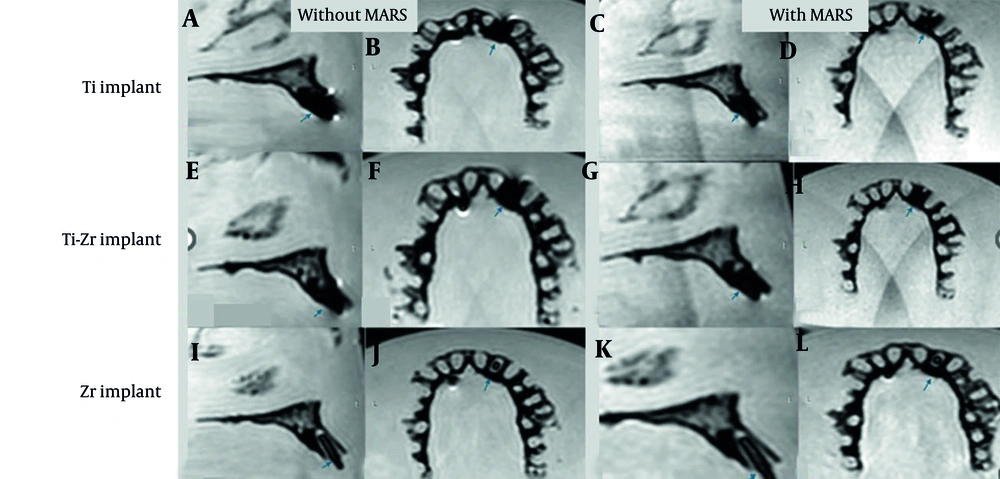

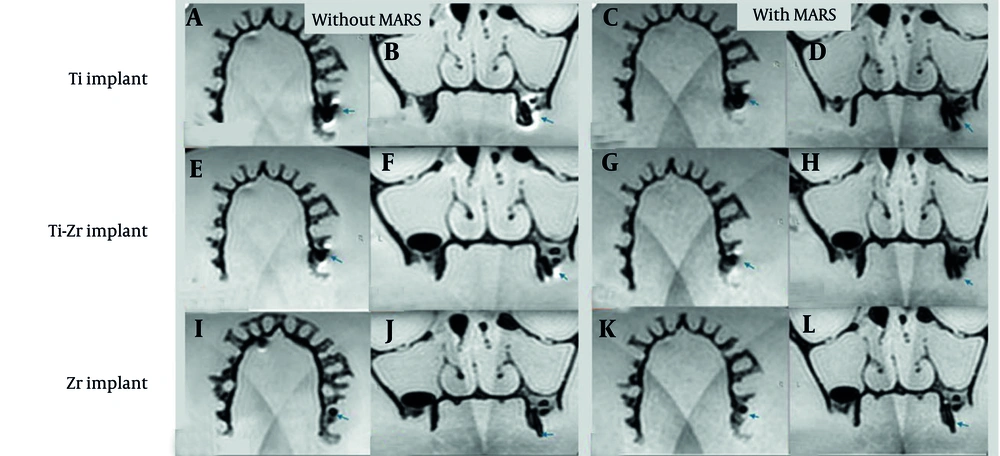

Volumes, calculated in cubic millimeters using the software’s “Statistics” tab, were reported separately for signal loss and pile-up artifacts. For signal loss, the implant volume was subtracted from the total segmented volume (15), while pile-up volumes were directly obtained from the segmented regions. Manual delineation of affected areas was performed slice by slice to maximize precision. Examples from the T2W sequence are shown in Figures 5. and 6.

T2-weighted (T2W) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images for titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (Ti-Zr), and zirconia (Zr) implants in the anterior maxillary region, without (A, B, E, F, I, and J) and with (C, D, G, H, K, and L) metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS) technique (Blue arrows denote to implant site).

T2-weighted (T2W) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images for titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (Ti-Zr), and zirconia (Zr) implants in the posterior maxillary region, without (A, B, E, F, I, and J) and with (C, D, G, H, K, and L) metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS) technique (Blue arrows denote to implant site).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD) were calculated for pile-up, signal-loss, and total artifact volumes across different implant materials and imaging conditions. A three-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the effects of implant material, jaw position, and MRI sequence. Although Levene’s test indicated some deviation from homogeneity of variances, the equal group sizes and high model fit (R2 = 0.963, adjusted R2 = 0.959) justified the use of ANOVA. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s test, with significance set at P < 0.05. Intra-rater reliability, assessed using a two-way mixed-effects model with consistency for single measures, was excellent for both signal loss (ICC = 0.993, 95% CI: 0.991 - 0.994) and pile-up (ICC = 0.995, 95% CI: 0.994 - 0.996).

3.6. Ethical Considerations

As this study was performed in vitro on non-human samples, no human subject concerns were involved. The study protocol was approved by the University Ethics Committee (IR.SBMU.DRC.REC.1403.050).

4. Results

This in vitro study evaluated the artifact volumes generated by Ti, Ti-Zr, and Zr dental implants placed in anterior and posterior regions of the maxilla. Multiple MRI sequences, both with and without MARS, were acquired, and artifact volumes were quantified.

4.1. Artifact Volumes Across Implant Materials

Mean ± SD values of signal-loss, pile-up, and total artifact volumes (mm3) for the three implant materials across different MRI sequences are summarized in Table 3.

| Implant materials; artifact types | T1W | T1W+MARS | T2W | T2W+MARS | PDW | PDW+MARS | 3D T1W | 3D T1W+MARS | 3D T2W | 3D T2W+MARS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | ||||||||||

| Signal loss | 304.4 ± 50.25 | 202.0 ± 13.45 | 299.6 ± 45.85 | 185.9 ± 10.60 | 272.6 ± 46.45 | 166.4 ± 15.60 | 354.1 ± 42.85 | 140.75 ± 12.60 | 347.7 ± 46.40 | 129.2 ± 7.85 |

| Pile-up | 260.7 ± 41.40 | 142.5 ± 16.25 | 272.1 ± 31.10 | 143.5 ± 22.75 | 228.6 ± 48.90 | 153.2 ± 17.95 | 269.6 ± 34.40 | 149.60 ± 28.30 | 257.9 ± 44.85 | 140.1 ± 18.40 |

| Total artifact | 565.1 ± 82.70 | 344.5 ± 14.85 | 571.7 ± 56.75 | 329.4 ± 27.85 | 501.2 ± 78.35 | 319.6 ± 27.00 | 623.7 ± 54.80 | 290.35 ± 30.75 | 605.6 ± 60.20 | 269.3 ± 19.30 |

| Ti-Zr | ||||||||||

| Signal loss | 178.1 ± 4.70 | 110.5 ± 10.75 | 174.9 ± 11.45 | 116.7 ± 9.70 | 148.8 ± 20.35 | 108.2 ± 12.95 | 197.0 ± 10.95 | 83.70 ± 6.20 | 185.4 ± 10.50 | 85.1 ± 8.05 |

| Pile-up | 107.8 ± 13.25 | 75.0 ± 8.45 | 125.9 ± 11.90 | 81.9 ± 10.60 | 107.5 ± 16.90 | 71.6 ± 8.15 | 129.1 ± 18.35 | 93.40 ± 6.25 | 118.1 ± 9.40 | 87.0 ± 6.40 |

| Total artifact | 268.9 ± 35.55 | 230.7 ± 14.55 | 246.0 ± 15.00 | 249.2 ± 14.30 | 225.4 ± 22.65 | 218.7 ± 23.15 | 254.9 ± 13.35 | 248.9 ± 17.95 | 242.0 ± 8.70 | 233.2 ± 12.40 |

| Zr c | ||||||||||

| Signal loss | 18.6 ± 1.75 | 22.9 ± 1.35 | 18.6 ± 1.90 | 20.8 ± 1.85 | 19.6 ± 2.00 | 22.0 ± 2.50 | 18.2 ± 1.05 | 20.6 ± 2.75 | 18.1 ± 1.35 | 20.4 ± 1.95 |

Abbreviations: T1W, T1-weighted; MARS, metal artifact reduction sequence; T2W, T2-weighted; PDW, proton density-weighted; 3D, 3-dimensional; Ti, titanium; Ti-Zr, titanium-zirconium; Zr, zirconia.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Values represent averages across anterior and posterior implant positions (n = 10 per cell, 5 repeats per position).

c Given the absence of pile-up artifacts associated with zirconia, only the signal loss values are presented in the table.

Three-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of implant material and MRI sequence on all artifact parameters (Table 4).

| Dependent variables; source | SS | df | MS | F | P-value | Partial η2 | Observed power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal loss | |||||||

| Material | 2428519.832 | 2 | 1214259.916 | 2627.625 | < 0.001 | 0.951 | 1.00 |

| Position | 6438.480 | 1 | 6438.480 | 13.933 | < 0.001 | 0.049 | 0.80 |

| Sequence | 479935.619 | 9 | 53326.180 | 115.396 | < 0.001 | 0.794 | 1.00 |

| Material * sequence | 339776.887 | 18 | 18876.494 | 40.848 | < 0.001 | 0.732 | 1.00 |

| Error | 124308.402 | 269 | 462.113 | - | - | - | - |

| Pile-up | |||||||

| Material | 520689.715 | 1 | 520689.715 | 921.041 | < 0.001 | 0.837 | 1.00 |

| Position | 3238.515 | 1 | 3238.515 | 5.729 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.67 |

| Sequence | 288436.269 | 9 | 32048.474 | 56.690 | < 0.001 | 0.740 | 1.00 |

| Material * sequence | 77746.817 | 9 | 8638.535 | 15.281 | < 0.001 | 0.434 | 1.00 |

| Error | 101193.621 | 179 | 565.327 | - | - | - | - |

| Total artifact | |||||||

| Material | 8905333.792 | 2 | 4452666.896 | 4902.346 | < 0.001 | 0.973 | 1.00 |

| Position | 1140.750 | 1 | 1140.750 | 1.256 | 0.263 | 0.005 | 0.12 |

| Sequence | 1241287.379 | 9 | 137920.820 | 151.850 | < 0.001 | 0.836 | 1.00 |

| Material * sequence | 955156.881 | 18 | 53064.271 | 58.423 | < 0.001 | 0.796 | 1.00 |

| Error | 244325.348 | 269 | 908.273 | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; df, degrees of freedom; MS, mean square; F, F-statistic; Partial η2, partial Eta squared.

a Material: Implant material (Ti: Titanium; Ti-Zr: Titanium-zirconium; Zr: Zirconia); Position: Implant position (anterior/posterior); Sequence: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequence [T1-weighted (T1W), T2-weighted (T2W), proton density-weighted (PDW), 3-dimensional (3D) T1W, 3D T2W, with/without Metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS)]; Material * sequence indicates a two-way interaction between implant material and MRI sequence.

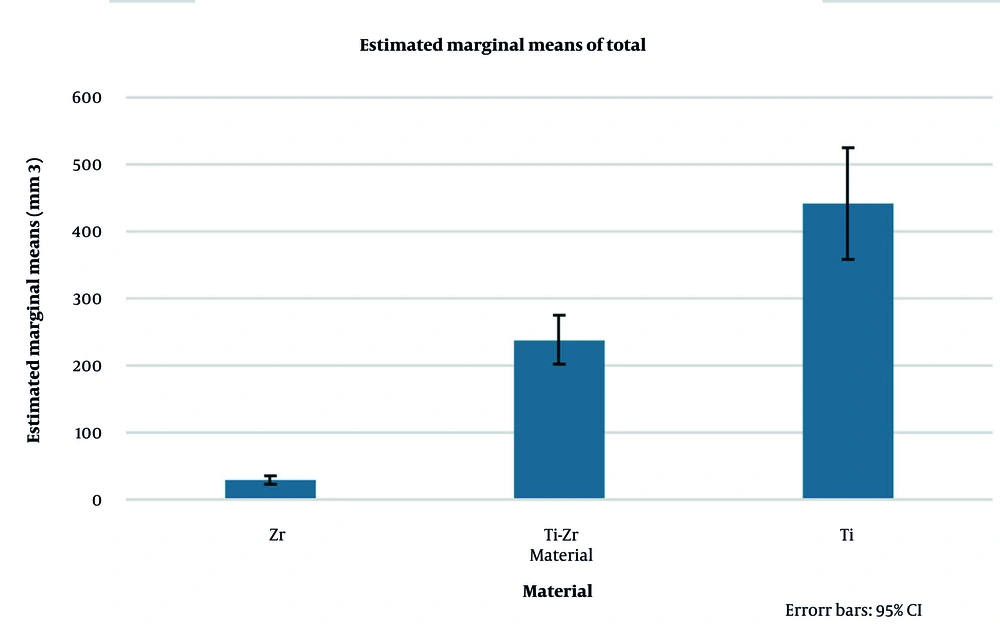

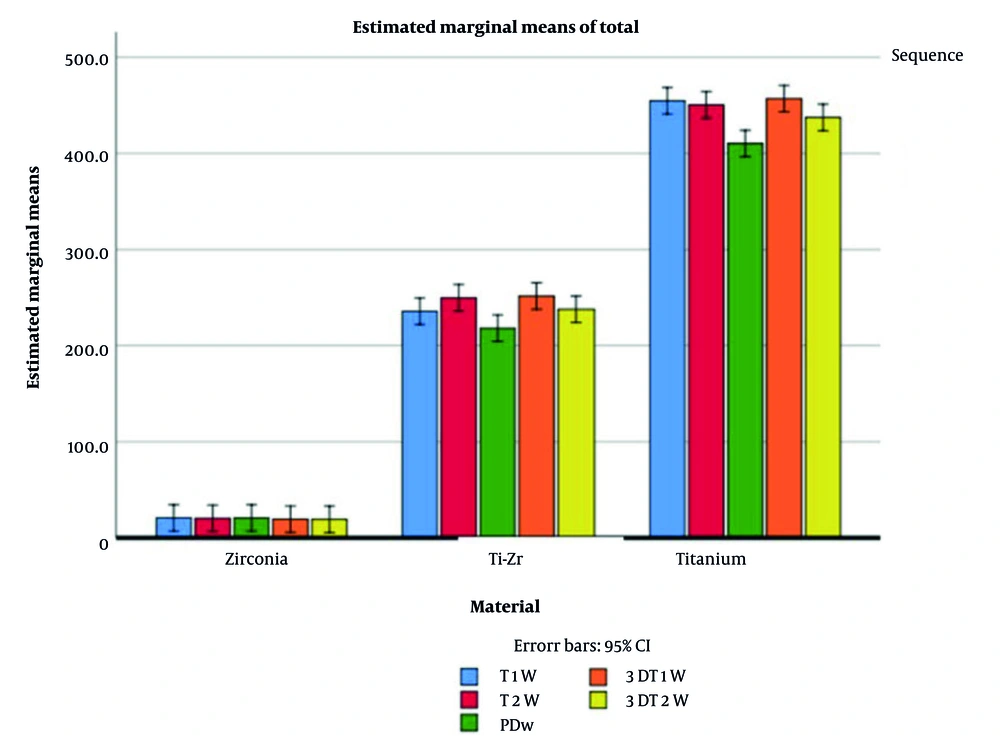

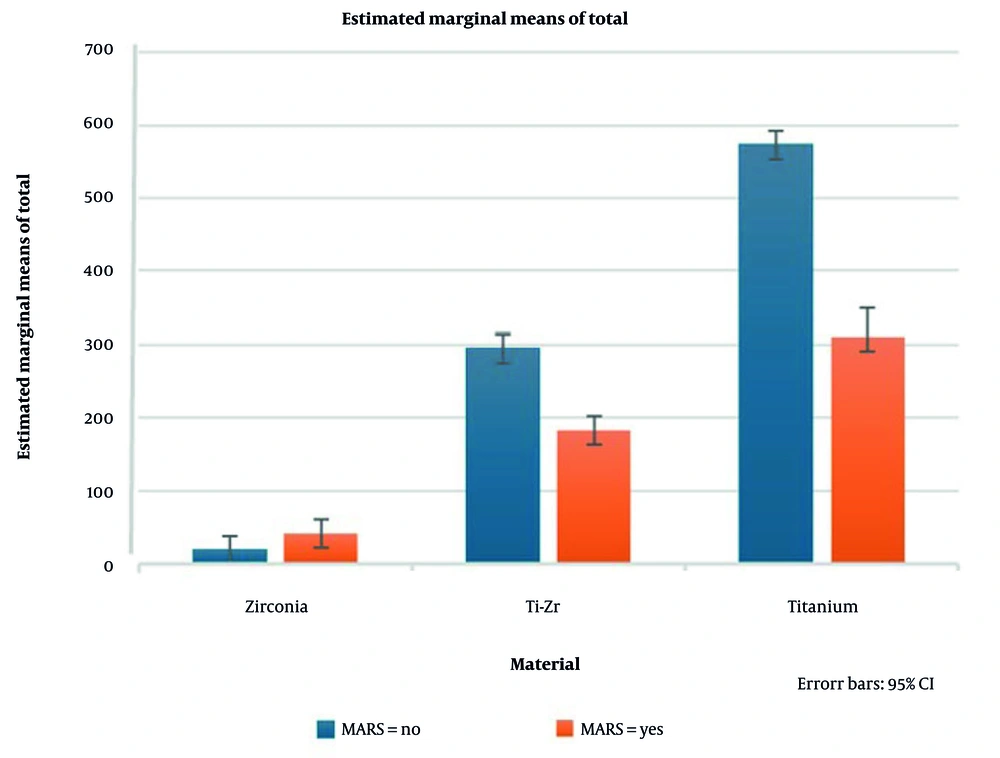

Implant material had a pronounced effect on artifact volumes: Signal loss (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.951, observed power = 1.00), pile-up (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.837, observed power = 1.00), and total artifact (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.973, observed power = 1.00). Post-hoc Tukey tests demonstrated that Zr implants consistently produced the lowest artifacts, Ti-Zr implants exhibited intermediate values, and Ti implants generated the highest artifact volumes (all pairwise comparisons P < 0.001, Table 4). Estimated marginal means for visual comparison are presented in Figures 7. and 8.

Estimated marginal means of total magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) artifact volumes for titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (Ti-Zr), and zirconia (Zr) implants across different MRI sequences, with and without metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS, error bars represent 95% confidence intervals).

4.1.1. Effect of Implant Position

Implant position influenced artifact parameters differently. Signal loss artifacts were significantly higher in anterior implants than in posterior implants (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.049, observed power = 0.80). Pile-up artifacts showed a minor but statistically significant increase in anterior implants (P = 0.018, partial η2 = 0.031, observed power = 0.67). In contrast, total artifact did not differ significantly between anterior and posterior positions (P = 0.263, partial η2 = 0.005, observed power = 0.12; Table 3). Given that position included only two levels (anterior vs. posterior), post-hoc tests were not applicable.

4.1.2. Effect of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequence

The MRI sequence had a significant impact on all artifact measures. Signal loss varied substantially across sequences [F(9, 269) = 115.40, P < 0.001, partial η2= 0.794, observed power = 1.00]. Pile-up artifacts also differed significantly [F(9, 179) = 56.69, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.740, observed power = 1.00], and total artifact was strongly influenced by sequence [F(9, 269) = 151.85, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.836, observed power = 1.00], highlighting the sequence choice as a major determinant of artifact magnitude (Table 3).

Pairwise comparisons across non-MARS sequences showed that 3D sequences consistently generated higher artifact volumes than 2D sequences.

- Signal loss: The 3D T1W and 3D T2W sequences produced significantly greater signal loss than 2D T1W, T2W, and PDW sequences (all P < 0.001). The PDW sequences consistently exhibited the lowest signal loss.

- Pile-up: The 3D T1W and 3D T2W sequences caused significantly higher pile-up compared to 2D sequences (all P < 0.001), with PDW sequences showing the smallest values. Some smaller differences, such as T2W vs. PDW, were also significant (P < 0.001).

- Total artifact: The 3D sequences resulted in significantly higher total artifact than 2D sequences (all P < 0.001). The PDW sequences consistently produced the lowest total artifact, while T2W sequences generally showed intermediate values (Table 4).

4.1.3. Effect of Metal Artifact Reduction Sequences

The MARS had a significant main effect on total artifact [F(1, 240) = 1177.91, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.831, observed power = 1.00], indicating a strong influence on artifact volume (Table 3). Post-hoc analysis using estimated marginal means (Table 5) revealed that the effect of MARS was material-dependent.

| Materials, sequence, MARS | Mean ± SE | Lower - upper bound (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|---|

| Zr | ||

| T1W | ||

| No | 18.620 ± 9.889 | 0.860 - 38.100 |

| Yes | 42.900 ± 9.889 | 23.417 - 62.383 |

| T2W | ||

| No | 18.620 ± 9.889 | 0.860 - 38.100 |

| Yes | 41.990 ± 9.889 | 22.507 - 61.473 |

| PDW | ||

| No | 19.600 ± 9.889 | 0.120 - 39.080 |

| Yes | 41.980 ± 9.889 | 22.497 - 61.463 |

| 3D T1W | ||

| No | 18.200 ± 9.889 | 1.280 - 37.680 |

| Yes | 40.600 ± 9.889 | 21.117 - 60.083 |

| 3D T2W | ||

| No | 18.100 ± 9.889 | 1.380 - 37.580 |

| Yes | 40.400 ± 9.889 | 20.917 - 59.883 |

| Ti-Zr | ||

| T1W | ||

| No | 285.900 ± 9.889 | 266.420 - 305.380 |

| Yes | 185.500 ± 9.889 | 166.020 - 204.980 |

| T2W | ||

| No | 300.800 ± 9.889 | 281.320 - 320.280 |

| Yes | 198.600 ± 9.889 | 179.120 - 218.080 |

| PDW | ||

| No | 256.300 ± 9.889 | 236.820 - 275.780 |

| Yes | 179.800 ± 9.889 | 160.320 - 199.280 |

| 3D T1W | ||

| No | 326.100 ± 9.889 | 306.620 - 345.580 |

| Yes | 177.100 ± 9.889 | 157.620 - 196.580 |

| 3D T2W | ||

| No | 303.500 ± 9.889 | 284.020 - 322.980 |

| Yes | 172.100 ± 9.889 | 152.620 - 191.580 |

| Ti | ||

| T1W | ||

| No | 565.100 ± 9.889 | 545.620 - 584.580 |

| Yes | 344.520 ± 9.889 | 325.040 - 364.000 |

| T2W | ||

| No | 571.700 ± 9.889 | 552.220 - 591.180 |

| Yes | 329.380 ± 9.889 | 309.900 - 348.860 |

| PDW | ||

| No | 501.150 ± 9.889 | 481.670 - 520.630 |

| Yes | 319.600 ± 9.889 | 300.120 - 339.080 |

| 3D T1W | ||

| No | 623.700 ± 9.889 | 604.220 - 643.180 |

| Yes | 290.340 ± 9.889 | 270.860 - 309.820 |

| 3D T2W | ||

| No | 605.600 ± 9.889 | 586.120 - 625.080 |

| Yes | 269.300 ± 9.889 | 249.820 - 288.780 |

Abbreviations: MARS, metal artifact reduction sequence; SE, standard error; Zr, zirconia; T1W, T1-weighted sequence; T2W, T2-weighted sequence; PDW, proton density-weighted sequence; 3D, 3-dimensional; Ti-Zr, titanium-zirconium; Ti, titanium.

a Material * sequence * MARS: Three-way interaction among implant material, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequence, and MARS.

b Dependent variables: Total.

For Ti and Ti-Zr implants, MARS consistently reduced total artifact across all sequences, confirming its efficacy in artifact suppression. Conversely, for Zr implants, MARS increased total artifact volumes, indicating a negative, material-specific effect. These differences were robust, with 95% confidence intervals showing no overlap between the reduced artifacts in Ti/Ti-Zr and the increased artifacts in Zr (Figure 9 and Table 5).

Estimated marginal means of total magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) artifact volumes for titanium (Ti), titanium-zirconium (Ti-Zr), and zirconia (Zr) implants across different MRI sequences, with and without metal artifact reduction sequences (MARS, error bars represent 95% confidence intervals).

5. Discussion

In this in vitro study, we quantified both signal-loss and pile-up artifacts, as well as their sum as total artifact volume, around three dental implant materials across multiple MRI sequences. Artifact extent decreased in the order: Ti > Ti-Zr > Zr. The PDW imaging yielded the smallest artifacts, while 3D acquisitions tended to increase artifact volume relative to 2D. The MARS markedly reduced artifacts for metallic implants (Ti and Ti-Zr) but paradoxically increased signal loss in Zr implants.

Artifact severity was strongly material-dependent. The Ti implants produced the largest artifacts, Zr the smallest, and Ti-Zr an intermediate extent. Quantitatively, Ti implants produced up to 40% larger artifact volumes than zirconia. These findings align with Demirturk Kocasarac et al. (2019) (16), who reported extensive MRI distortions for Ti and Ti-Zr implants, while Zr exhibited minimal artifact. Unlike previous studies that focused solely on signal loss (6, 16, 17), our study evaluated both signal loss and pile-up artifacts, offering a more comprehensive assessment of susceptibility-induced distortions. Furthermore, the application of three-dimensional volumetric analysis in our study enabled a more complete measurement of total artifact burden compared with conventional 2D linear assessments. Both approaches consistently confirmed Zr as the most MRI-compatible material, Ti as the least compatible, and Ti-Zr as intermediate. However, other artifact types, including geometric distortions, warrant further investigation in future studies.

Artifact magnitude varied across MRI sequences. Signal loss artifacts in 2D sequences (T1W, T2W, and PDW) did not differ significantly (P > 0.05), indicating that selection among these sequences has minimal impact on signal loss alone. However, 3D acquisitions generally produced greater signal loss artifacts than their 2D counterparts, with significant differences observed in T1W (P = 0.002) and T2W (P = 0.018) images, suggesting that 3D imaging may exacerbate artifact extent in clinical settings.

Regarding total artifact, PDW sequences consistently produced smaller artifacts compared with T2W (P < 0.001), highlighting PDW as the optimal sequence for minimizing overall susceptibility-induced distortions in dental implant imaging. Differences between 3D and 2D sequences for total artifact were significant only in T1W (P = 0.03), whereas T2W showed no meaningful difference (P = 0.895). These findings are consistent with Valizadeh et al. (2017) (18), who evaluated 2D and 3D sequences but measured only signal-loss artifacts, and partially align with Smeets et al. (2017) (19), who observed larger signal voids in T2W images. The discrepancies with Smeets et al. likely stem from methodological differences: While Smeets et al. primarily employed two-dimensional line measurements and focused on signal loss, our study applied three-dimensional volumetric analysis and additionally quantified pile-up artifacts, providing a more comprehensive assessment of susceptibility-induced distortions.

Overall, these results underscore PDW sequences as the preferred choice in clinical MRI of dental implants, particularly when minimizing artifacts is crucial. Moreover, 3D imaging should be applied cautiously, especially in T1W sequences, due to the potential for increased artifact extent. This may be due to the volumetric acquisition approach of 3D sequences, which accumulates magnetic field inhomogeneities across the slab; 2D sequences, by acquiring data slice-by-slice, restrict such distortions to single slices. In 3D sequences, the entire image volume is acquired as a single slab, so magnetic field distortions caused by the implant accumulate across the volume. Moreover, 3D acquisitions typically have longer readout times and greater sensitivity to field inhomogeneities, which further exaggerates signal loss and pile-up regions. In contrast, 2D sequences acquire data slice-by-slice, confining distortions to individual slices and reducing the overall propagation of artifacts. This limitation results in lower artifact intensity in 2D sequences. Furthermore, from a physical standpoint, 3D sequences are more sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneities due to longer readout times, which causes artifacts to appear more extensive and pronounced.

The MARS significantly decreased both signal loss and pile-up artifacts in Ti and titanium-zirconium implants (signal loss reduced from 304.4 to 202.0 mm3 in Ti and from 178.1 to 110.5 mm3in Ti-Zr), confirming its effectiveness in metallic implant imaging. The reduction was more pronounced for signal loss than for pile-up, suggesting that MARS preferentially mitigates dephasing-related signal voids rather than displacement artifacts. In contrast, MARS increased artifact volumes in zirconia implants. This effect is likely due to overcorrection by the MARS algorithm, which is primarily designed to reduce metal-induced artifacts. Additionally, sequence parameter modifications, such as bandwidth adjustments, may inadvertently increase signal loss in low-susceptibility materials like zirconia.

Artifact distribution also depended on implant position. The Ti implants produced greater signal loss artifacts in the anterior maxilla, whereas Ti-Zr implants showed only a slight increase in anterior signal loss with minimal change in pile-up. The Zr implants exhibited no positional effect on artifact magnitude. Importantly, implant position did not significantly affect total artifact (P = 0.263), although total artifact in the anterior region was slightly higher. These findings are consistent with Smeets et al. (2017) (19), who reported that signal voids are more prominent when implants are oriented perpendicular to the main magnetic field (transverse direction). The observed material- and position-specific effects emphasize the importance of customizing MRI protocols according to implant type and orientation to optimize image quality and assessment of surrounding tissues.

Susceptibility artifacts from Ti and Ti-Zr implants tend to be localized along the implant axes, consistent with Bohner et al. (2020) (12), who reported similar distribution patterns in apical, mesio-distal, and vestibulo-lingual directions, with Ti implants distorting surrounding tissues by up to 3.55 mm.

In this study, implants were placed in the maxilla because its attachment to the skull and proximity to critical structures, such as the skull base, allowed a stable and realistic experimental setup, enabling better evaluation of artifact effects on the skull. Both anterior and posterior regions were included, as implant orientation differs between them (labial inclination anteriorly versus near-perpendicular posteriorly), allowing assessment of artifact variation across anatomical orientations.

Optimizing MRI parameters can further improve image quality in the presence of metallic implants. Lower-field scanners tend to produce less severe artifacts, and careful adjustment of phase-encoding and frequency-encoding directions may help minimize artifact propagation, particularly when artifacts align with specific encoding axes (20, 21).

Based on the findings of this study, practical recommendations for clinicians and technicians can be provided. Clinicians are advised that in patients with implants located near critical anatomical structures requiring precise evaluation, 2D sequences, particularly PDW sequences, should be preferred to minimize artifacts. For MRI technicians, the positive and significant effects of the MARS technique in dental implant imaging should not be overlooked. This study does not aim to recommend Zr implants over other materials, as clinical decisions must consider factors such as osseointegration and surgical requirements. However, from an MRI imaging perspective, Zr demonstrates more favorable artifact characteristics.

This study has several limitations. Artifact assessment was performed in an in vitro phantom using a 1.5 T MRI system, which may not fully represent in vivo human tissues. Factors such as patient motion, tissue heterogeneity, and interactions with other dental restorations could affect artifact appearance, and results may differ with other scanner vendors or higher field strengths (e.g., 3 T). Only signal loss and pile-up artifacts were evaluated, while other distortions or interactions with metal-ceramic restorations were not considered. Longer scan times in some sequences may limit clinical applicability due to potential motion artifacts. Finally, measurements were performed by a single rater, and inter-rater reliability was not assessed. Future studies should include a wider range of clinical conditions and optimized sequence protocols to improve generalizability.

In conclusion, MRI artifact severity depends on implant material, decreasing from Ti to Ti-Zr and being lowest in Zr, with PDW imaging producing the fewest artifacts. The MARS technique effectively reduces artifacts in metallic implants but, paradoxically, increases artifacts in Zr, highlighting the need for caution when applying MARS to non-metallic implants. Implant position also influences artifact extent: Signal loss is greater in the anterior maxilla, pile-up shows a slight increase in the anterior region, and there is no significant difference in total artifact.