1. Introduction

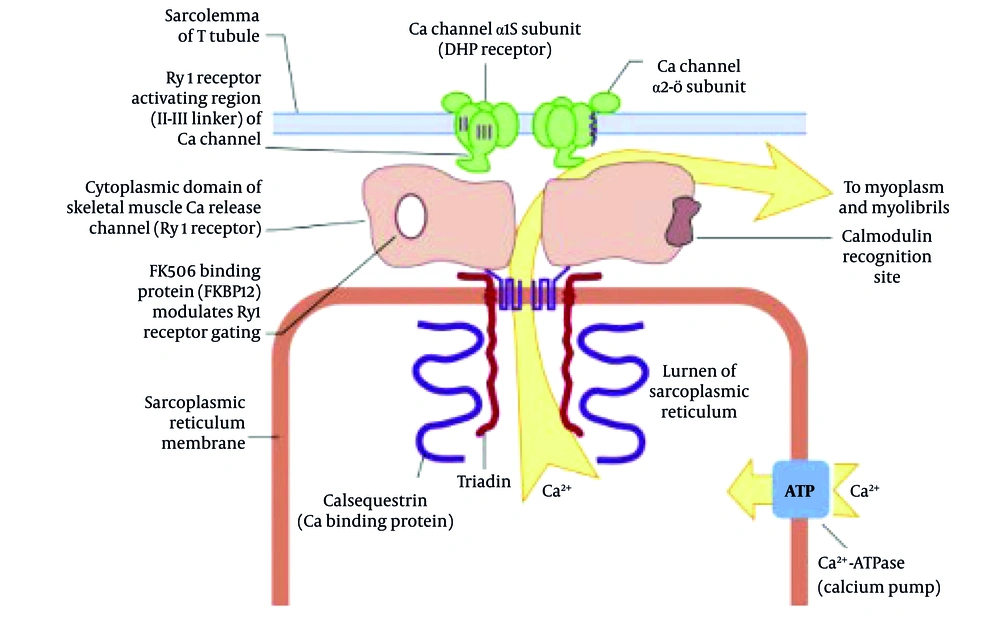

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a rare, life-threatening pharmacogenetic disorder characterized by a hypermetabolic state in skeletal muscle following exposure to specific anesthetic agents, such as depolarizing muscle relaxants (e.g., succinylcholine) and volatile anesthetics (e.g., halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane) (1-3). This condition is primarily associated with mutations in the ryanodine receptor type 1 (RYR1) gene or, less commonly, the CACNA1S gene, both of which are critical in regulating calcium homeostasis within skeletal muscle cells (4). A disruption in calcium regulation leads to uncontrolled calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), resulting in sustained muscle contraction, increased metabolism, and heat production (5). When exposed to triggering agents like isoflurane, mutated RYR1 receptors cause excessive calcium release from the SR, leading to sustained muscle contraction, hypermetabolism, ATP depletion, lactic acidosis, and heat production (6) (Figure 1). Clinically, MH presents with hypercarbia, unexplained tachycardia, rapid rise in body temperature, muscle rigidity, and mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis (7). In severe cases, it can lead to rhabdomyolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute renal failure, hyperkalemia, and cardiac arrest (8). The estimated incidence of MH ranges from 1:5,000 to 1:100,000 anesthetic exposures, depending on the population studied and the use of triggering agents (9). Despite its rarity, MH remains a significant concern for anesthesiologists due to its rapid onset and potential for catastrophic outcomes if not promptly recognized and managed (10). The diagnosis of MH is primarily clinical and is based on the identification of characteristic signs and symptoms during or shortly after anesthesia (11). Early recognition is essential for initiating appropriate management, including discontinuation of triggering agents, administration of 100% oxygen, and rapid administration of dantrolene, the only effective pharmacologic treatment available (12). Dantrolene works by inhibiting calcium release from the SR, thereby reducing muscle rigidity and hypermetabolism (13). Prompt administration of dantrolene has been shown to reduce mortality rates from MH from approximately 80% to less than 5% (14). In this report, we present a case of MH triggered by isoflurane in a young woman undergoing elective septorhinoplasty. The rapid onset of symptoms and the effective management with dantrolene highlight the importance of vigilance, preparedness, and adherence to established protocols for MH in all anesthesia settings. This case also underscores the critical role of continuous monitoring, particularly capnography, in detecting early signs of MH and preventing fatal complications.

Exposure to a triggering volatile anesthetic (e.g., isoflurane, as used in this case) in a susceptible individual leads to uncontrolled calcium (Ca2⁺) release through the mutated RYR1 in the SR. This calcium overload drives sustained muscle contraction, hypermetabolism, and the clinical signs observed in this patient (hypercapnia, tachycardia, hyperthermia). Dantrolene acts by inhibiting this pathological calcium release, thereby terminating the crisis.

2. Case Presentation

A 21-year-old woman (height: 162 cm; weight: 58 kg; Body Mass Index: 22.1 kg/m2) was scheduled for elective septorhinoplasty. She was classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I. The patient reported no significant medical history of chronic diseases, no known drug allergies, and no previous history of adverse reactions to anesthesia in herself or her family. Specifically, there was no personal or family history of MH, muscular dystrophies, or other related genetic disorders. Her surgical history was negative. She was not on any regular medications, including antipsychotics or serotonergic drugs, and denied the use of illicit substances. Preoperative vital signs were normal: Blood pressure 110/70 mmHg, heart rate 72 beats per minute, respiratory rate 13 breaths per minute, and afebrile. Preoperative laboratory tests, including complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, were within normal limits. As the patient was asymptomatic with no clinical signs of thyroid disease (e.g., goiter, exophthalmos, tremor, or palpitations), thyroid function tests (TFTs) were not performed preoperatively as per our institutional protocol for healthy, low-risk patients.

2.1. Anesthesia Induction and Intraoperative Course

Anesthesia was induced with midazolam (1 mg), fentanyl (200 mcg), lidocaine (50 mg), propofol (120 mg), and atracurium (40 mg). The patient was successfully intubated with a size 7 spiral tube and connected to a capnograph. Maintenance anesthesia was achieved using isoflurane (1.2%), nitrous oxide (50%), and remifentanil (0.1 mcg/kg/min). For the first 60 minutes, the patient remained stable with blood pressure of 90/70 mmHg, end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) between 30 - 35 mmHg, and heart rate fluctuating between 65 - 70 beats per minute.

2.2. Development of Malignant Hyperthermia

Approximately 75 minutes into the surgery, the patient exhibited a sudden increase in ETCO2 (peaking at 50 - 60 mmHg, then reaching 110 mmHg), a rapid rise in body temperature to 42.5°C (measured in the axilla), tachycardia (heart rate of 120 bpm), and hypertension (blood pressure 190/110 mmHg). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of MH.

2.3. Management and Treatment

Isoflurane and remifentanil were immediately discontinued, and the anesthesia machine was flushed with 100% oxygen at 10 L/min. Dantrolene was administered intravenously and further doses continued for three days as per protocol [dantrolene was given at 2.5 mg/kg IV initially, repeated at 10-minute intervals to a total of 10 mg/kg as needed (10)]. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis revealed severe acidosis (pH 6.99, PCO2 102 mmHg, HCO3 24.6 mEq/L). A detailed timeline of key interventions and diagnostic tests is presented in Table 1. The initial ABG and creatine phosphokinase (CPK) tests were drawn immediately following the onset of hypermetabolic signs (e.g., hypercapnia, tachycardia). Creatine phosphokinase test results for the patient were 744 U/L. Active cooling measures included infusion of cold intravenous fluids, nasogastric lavage with cold saline, and ice packs around the patient until the temperature normalized to 38°C. The patient also received sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq), Lasix (20 mg), and 4 liters of crystalloid fluids. Her clinical condition gradually improved, with ETCO2 normalizing to 35 - 40 mmHg, heart rate to 80 bpm, blood pressure to 125/85 mmHg, and ABG normalized (pH 7.42, PCO2 37 mmHg, HCO3 24 mEq/L). The timely initiation of these measures likely prevented complications such as arrhythmia, acute kidney injury, or DIC. Calcium channel blockers were avoided, as their combination with dantrolene can cause hyperkalemia and cardiovascular collapse. The patient was extubated once fully conscious and stable. Continuous monitoring and supportive care were provided for seven days in the ICU, and the patient was discharged with normal laboratory tests and no residual complications. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report, including anonymized clinical details and images.

| Time (Min Post-induction) | Event/Intervention/Finding |

|---|---|

| 0 | Anesthesia induced with midazolam, fentanyl, lidocaine, propofol, and atracurium. Maintenance with isoflurane |

| ~ 75 | First sign: Sudden increase in ETCO2 (50 - 60 mmHg) |

| ~ 77 | ETCO2 peaked at 110 mmHg. Tachycardia (120 bpm) and hypertension (190/110 mmHg) noted. |

| ~ 78 | Isoflurane and remifentanil discontinued. Anesthesia circuit flushed with 100% O2 at 10 L/min. |

| ~ 80 | Axillary temperature measured at 42.5°C. First dose of dantrolene (2.5 mg/kg IV) administered. |

| ~ 85 | First ABG: pH 6.99, PCO2 102 mmHg, HCO3 24.6 mEq/L. Active cooling initiated (cold IV fluids, ice packs). |

| ~ 85 | Initial CPK: 744 U/L |

| ~ 90 | Sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq) administered. |

| ~ 95 | Second dose of dantrolene administered. |

| ~ 120 | Follow-up ABG: pH 7.42, PCO2 37 mmHg, HCO3 24 mEq/L |

Abbreviations: ABG, arterial blood gas; CPK, creatine phosphokinase.

3. Discussion

This case of MH highlights several key considerations in the recognition and management of this rare but potentially fatal anesthetic complication. The patient, a young woman with no prior history suggestive of MH, developed symptoms approximately 75 minutes after the administration of isoflurane. This presentation underscores that MH can occur unpredictably and in patients without a known genetic predisposition, emphasizing the need for heightened vigilance whenever triggering agents are used.

Differential diagnoses for MH include other hypermetabolic or hyperthermic conditions, such as thyroid storm, sepsis, pheochromocytoma, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and serotonin syndrome. Thyroid storm can be ruled out in the absence of thyroid disease and without signs of hyperthyroidism, such as exophthalmos or a goiter, as well as normal TFTs (TSH, T3, T4) (15). Sepsis should be considered when there is evidence of infection, but the rapid onset of symptoms and absence of infection signs make it less likely in this case (16). Pheochromocytoma typically presents with episodic hypertension and palpitations, which were not observed in this patient’s medical history (17). The NMS and serotonin syndrome are primarily distinguished by their triggering medications; NMS is associated with antipsychotic use and serotonin syndrome with serotonergic drugs, both of which were absent in this patient’s medication profile (18).

3.1. Pathophysiology

Malignant hyperthermia is linked to defective RYR1 channels leading to calcium overload in skeletal muscle fibers. This activates contractile and metabolic cascades, increasing CO2 production and body temperature. Dantrolene antagonizes RYR1-mediated calcium release, stabilizing muscle cell metabolism.

3.2. Management Strategies

The mainstay of MH management includes the immediate cessation of all triggering agents, hyperventilation with 100% oxygen, active cooling, and the prompt administration of intravenous dantrolene (10). In this case, early recognition allowed for rapid discontinuation of isoflurane and the initiation of dantrolene, which likely contributed to the patient’s favorable outcome. The patient received 2.5 mg/kg of dantrolene intravenously, repeated as necessary, which aligns with current treatment protocols (8).

Cardiac arrhythmias in MH patients are often secondary to hyperkalemia, acidosis, or the direct effects of hyperthermia on the myocardium. Antiarrhythmic treatment should focus on addressing the underlying causes. First-line treatments include correcting hyperkalemia with intravenous calcium gluconate or calcium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, and insulin with glucose to shift potassium into cells (19). If arrhythmias persist despite correction of metabolic disturbances, medications such as amiodarone or lidocaine may be used cautiously. Drugs like calcium channel blockers should be avoided, as they can exacerbate hyperkalemia and worsen MH symptoms (20).

Acute tubular necrosis can occur in MH due to rhabdomyolysis, which releases myoglobin into the bloodstream, causing renal damage. Prevention strategies focus on maintaining adequate renal perfusion and urine output. This includes aggressive intravenous hydration with isotonic crystalloids (e.g., normal saline) to achieve a urine output of at least 2 mL/kg/h (21). Mannitol or furosemide may be used to promote diuresis if necessary, and urine alkalinization with sodium bicarbonate can help prevent myoglobin precipitation in the renal tubules (22).

This case illustrates the importance of preparedness in managing MH. All anesthesia departments should establish and regularly update MH protocols, including staff training, simulation exercises, and ensuring that dantrolene is readily available. The use of MH carts containing necessary medications and equipment (e.g., dantrolene, cooling supplies, and monitoring devices) can significantly reduce the time to treatment and improve outcomes (21). Regular drills and education on the early signs of MH, the use of capnography, and the administration of dantrolene are vital for maintaining readiness.

3.3. Role of Genetic Testing and Family History

Although our patient had no known family history of MH, genetic testing can be useful for identifying susceptible individuals, particularly in families with a known history of MH or related disorders (23). The caffeine-halothane contracture test (CHCT) and molecular genetic testing for RYR1 and CACNA1S mutations remain the gold standards for diagnosing MH susceptibility (24). Early identification of at-risk individuals can guide the choice of anesthetic agents and inform perioperative management to avoid triggering agents.

3.4. Future Directions

Recent advancements in understanding the pathophysiology of MH have opened avenues for new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. For example, studies are investigating the use of alternative diagnostic methods, such as measuring ATP levels in platelets, which may offer a less invasive way to screen for MH susceptibility (25). Additionally, ongoing research into the molecular mechanisms underlying MH may lead to the development of new therapeutic agents targeting the RYR1 receptor or other pathways involved in calcium regulation (26).

The successful management of the MH crisis involved timely coordination among multiple clinical departments. The anesthesia team initiated emergency protocols and administered dantrolene. The surgical team cooperated promptly to halt the procedure and assist with supportive measures. ICU specialists provided continuous monitoring and guided post-crisis management over the following days. Additionally, the laboratory team expedited critical diagnostics, including ABGs and serum CPK, while the pharmacy department ensured rapid access to dantrolene. This collaborative approach was vital in stabilizing the patient and achieving a full recovery.

The clinical presentation in this case — sudden hypercapnia, tachycardia, and rapid hyperthermia approximately 75 minutes after induction with isoflurane — aligns with the typical signs described in previous reports of MH (1). However, two features make this case noteworthy. The absence of known risk factors: The patient had no personal or family history of MH and no prior exposure to triggering agents, highlighting the importance of preparedness even in “low-risk” individuals. Prompt diagnosis via capnography: The first sign was an abrupt rise in ETCO2, underlining the value of continuous capnographic monitoring during general anesthesia. This case supports existing literature that capnography may be the earliest and most sensitive indicator of MH onset, often preceding hyperthermia or muscle rigidity (2). Moreover, the patient’s rapid and complete recovery with no neurological, renal, or cardiovascular complications demonstrates the critical role of early intervention, access to dantrolene, and adherence to structured MH protocols. Compared to published case series, this report contributes further real-world evidence supporting standard MH management pathways and may serve as a teaching case for simulation-based training in anesthesiology.

This case report has several limitations. First, genetic testing was not performed to confirm susceptibility to MH. Second, core temperature monitoring (e.g., esophageal or rectal) was not available, and axillary temperature was used instead, which may underestimate the true core temperature. Third, serum and urine myoglobin levels were not measured due to laboratory constraints, which would have provided a clearer assessment of rhabdomyolysis severity. Furthermore, while the initial CPK was elevated, peak levels were not tracked due to the patient’s rapid improvement. Although TFTs were normal post-event, they were not part of the routine preoperative workup for this asymptomatic patient. Finally, long-term follow-up for renal function or recurrence risk was not available due to the patient’s loss to follow-up after discharge; however, given the resolved clinical and laboratory parameters, the risk of long-term sequelae is considered low.

3.5. Conclusions

Malignant hyperthermia is a rare but critical condition that requires rapid diagnosis and intervention to prevent serious complications. This case reinforces the necessity of continuous monitoring, particularly capnography, and the need for the immediate availability of dantrolene and established emergency protocols in every operating room. Awareness of MH and preparedness to manage it effectively are essential components of safe anesthetic practice. Future research should focus on refining diagnostic tools and exploring novel treatment strategies to further improve patient outcomes.