1. Background

Neuromuscular blocking agents have played a critical role in anesthesia since 1942, with the introduction of tubocurarine (1). Following this, many drugs, including cisatracurium, were developed for use in advanced and safe anesthetic procedures (2). Cisatracurium is an intermediate-acting non-depolarizing agent that induces neuromuscular blockade in skeletal muscles by competitively binding to nicotinic receptors at the neuromuscular junction, thereby inhibiting acetylcholine's action (1).

The onset of neuromuscular blocking agents depends on their ability to bind to receptors at the neuromuscular junction. When these drugs are administered through a peripheral vein, they must travel through the circulatory system to reach their target, which is influenced by appropriate cardiac output and blood flow to the target organs (3, 4). Any disruption in the delivery of these drugs to the neuromuscular junction — such as insufficient cardiac output or occlusion in blood vessels — can reduce their efficacy and function.

One commonly used device in limb surgery is the tourniquet, which helps reduce blood loss during orthopedic and vascular procedures. It seems that the use of a tourniquet may disrupt the distribution of neuromuscular blocking agents to their action sites (4, 5). Several questions arise regarding the effect of the tourniquet on neuromuscular function and the activity of neuromuscular blocking agents.

1. Does a tourniquet alone alter neuromuscular physiology and monitoring?

2. Does a tourniquet affect the activity, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of neuromuscular blocking agents?

3. What happens to neuromuscular blockade and its recovery when the tourniquet is deflated?

To address these questions, numerous studies have been conducted. For example, E. Armstrong demonstrated that the use of a tourniquet to occlude blood flow above the elbow significantly reduces muscle twitch heights compared to normal blood flow, indicating greater muscle fatigue (6, 7). Seo et al., in another study, observed that the train-of-four (TOF) ratio increased in 21 out of 30 patients who received rocuronium during anesthesia after tourniquet deflation, while it decreased in 9 patients. They concluded that deflation of the tourniquet alters neuromuscular blockade, and monitoring during such procedures is essential (8).

Another issue during surgeries with a tourniquet is administering the maintenance dose of neuromuscular blocking agents after deflation. If this dose is administered without considering the effects of an inflated tourniquet, appropriate blockade may not be achieved in the sequestrated limb.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study is to focus on the effects of the tourniquet on cisatracurium use during anesthesia and the impact of tourniquet inflation on TOF monitoring.

3. Methods

This double-blind randomized clinical trial was conducted in the general operating rooms of Firoozgar and Hazrat-e-Rasool hospitals from October 2021 to July 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1399.632) and registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20151107024909N11). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they entered the study. We studied two groups of patients: One group received cisatracurium after tourniquet inflation (group A), and the other received the drug before tourniquet inflation (group B). To conduct this study, we selected 82 adult patients aged 20 to 65 who underwent general surgery. According to the study by Yildirim et al. (9), the mean time to 75% recovery in the tourniquet arm was 33.48 ± 3.32 minutes for the atracurium group and 37.32 ± 3.24 minutes for the vecuronium group. Considering a study power of 80% and a 95% confidence interval, the required sample size was calculated using the following formula, which resulted in 12 participants per study arm:

The patients were evaluated according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and after obtaining consent, 27 patients were selected. The patients were randomly allocated to one of the two groups using the balanced block randomization method (block size = 4). Random allocation software was used to determine the sequence of blocks. Each block contained two "A"s for "After" and two "B"s for "Before". For each eligible patient, the group assignment was determined based on a randomly selected sequence, and after completing one block (n = 4), the next randomized sequence was used to complete the next block until all eight blocks were finished.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: Patients who were undergoing elective general surgery under general anesthesia, aged between 20 - 65 years old, with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 18 - 30, and classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I. Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of addiction, patients undergoing surgery on both upper limbs, elevated ICP, tumors distal to the tourniquet, fractures or infections in the upper limbs, acidosis, sickle cell disease, peripheral vascular disease, a history of dialysis, neuromuscular disease, previous surgery on the upper limbs, cardiopulmonary disease, liver and kidney disease, or a history of receiving drugs such as aminoglycosides, polymyxins, lincomycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, calcium, magnesium, lithium, verapamil, amlodipine, furosemide, dantrolene, anticonvulsants, azathioprine, or those in emergency or unstable situations during surgery. These inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on conditions affecting tourniquet use or hemodynamic status as described in the literature (4, 5).

Upon entering the operating room, demographic characteristics (age, gender, height, weight, BMI, and ideal body weight) were recorded. ECG, SpO2, blood pressure, and heart rate were monitored, and each patient received 5 cc/kg of NaCl 0.9% via a peripheral intravenous line and was preoxygenated with 70% oxygen through a face mask. A tourniquet was applied to the midportion of the humerus on the limb that did not have a catheter, and TOF watch pads were placed on the ulnar nerve, 1 cm proximal to the wrist fold, with a 3 to 6 cm distance between the pads on both upper limbs to detect adductor pollicis muscle contractions (5, 10, 11) (Figure 1). Additionally, we ensured environmental conditions and prerequisites for each patient, including maintaining a skin temperature of at least 32°C at the stimulation site, performing initial calibration before administering the neuromuscular blocking agent, and recording the initial contraction response for later comparisons.

In both groups, patients were sedated with midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) and fentanyl (2 µg/kg), followed by an intravenous dose of lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg). The TOF monitor was calibrated, and anesthesia induction began with the infusion of propofol (2 mg/kg). In group A, the tourniquet was first inflated to 100 mmHg above the patient's systolic pressure, followed by the infusion of cisatracurium (0.2 mg/kg based on ideal body weight). In group B, the tourniquet was inflated after the administration of cisatracurium, once the TOF count reached 0 in one of the limbs. For both groups, the times at which the TOF count reached 0, 1, and 2, as well as the temperatures at those points, were recorded for both limbs.

During surgery, all patients received a continuous infusion of propofol (50 - 150 µg/kg/min), with anesthesia depth monitored using a Bispectral Index (BIS) monitor. Once the TOF count reached 2 in the hand that didn't have a tourniquet, a maintenance dose of cisatracurium was administered to continue the surgery, and the tourniquet was deflated to prevent neuromuscular adverse effects due to ischemia (6). One patient in group A and two patients in group B had their intervention discontinued due to complications during anesthesia. In this study, all patients were unaware of the medication type and intervention because they were under anesthesia. The anesthesiologist who evaluated and collected the data was also unaware of the medication type and intervention.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26, with a significance level set at P < 0.05. Paired t-tests were used to assess differences within each group, while independent t-tests were used to compare differences between the two groups.

4. Results

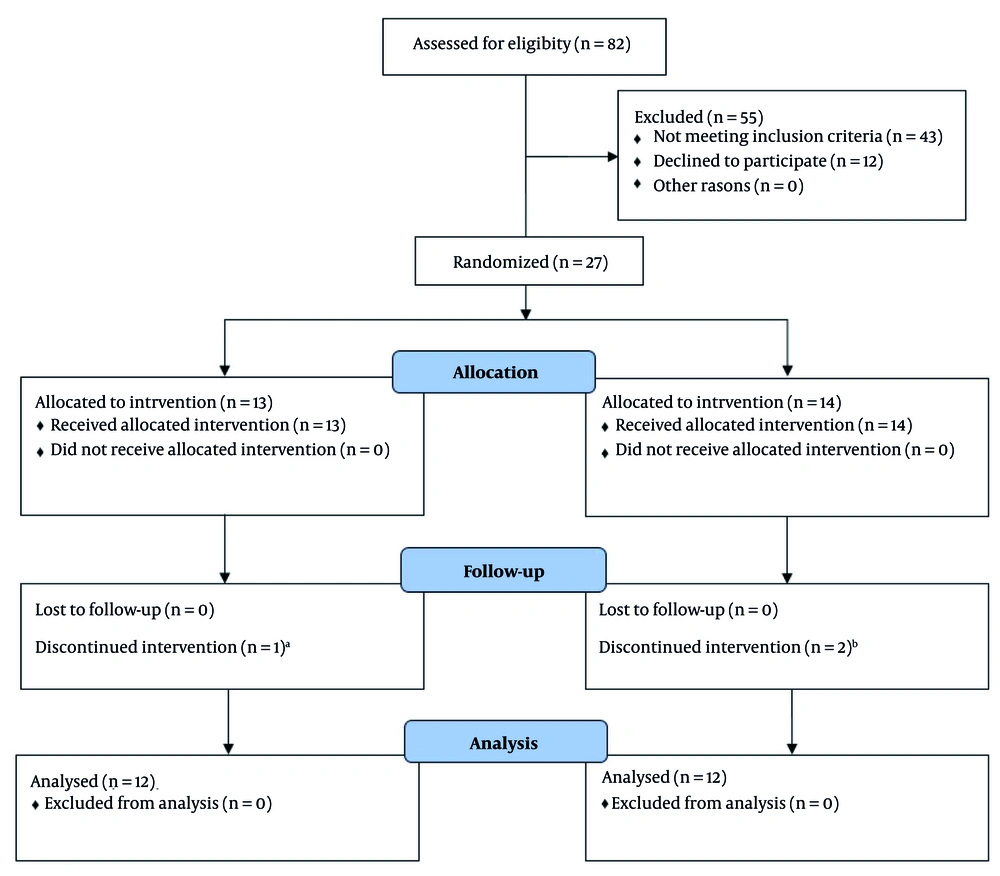

We studied two groups of patients: One group received cisatracurium after tourniquet inflation (group A), while the other received the drug before tourniquet inflation (group B). To assess this, we examined 27 adult ASA class patients, aged 20 to 65 years, undergoing general surgery. Participants were evaluated according to inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided their consent. They were randomly assigned to one of the two groups (Figure 2).

CONSORT diagram for selecting patients: A, appearance of severe mottling in the arm with the tourniquet; B, one case due to the appearance of severe mottling in the arm with the tourniquet, and the other case due to the return of breathing effort when the train-of-four (TOF) COUNT showed zero.

In this study, 12 patients in group A, who received cisatracurium after tourniquet inflation, were compared with 12 patients in group B, who received cisatracurium before tourniquet inflation. The baseline characteristics of patients in both groups were compared. As shown, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, weight, ideal body weight, and BMI (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered after inflation of the tourniquet.

c Cis-atracurium administered before inflation of the tourniquet.

There were no significant differences in heart rate, blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), and oxygen saturation (SpO2) between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 2).

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered after inflation of the tourniquet.

c Cis-atracurium administered before inflation of the tourniquet.

In group A, where cisatracurium was administered after tourniquet inflation, the TOF count reached zero in the non-tourniqueted arms after 244.83 ± 64.53 seconds. However, in the tourniqueted arms, the TOF count remained at 4, with only a slight reduction in the TOF ratio (down to 0.91). There was no significant difference in limb temperatures during this period (31.7 ± 1.4°C vs. 31.75 ± 1.45°C, P = 0.36). In the perfused arm, the TOF count recovered from 0 to 1 — indicating the duration of complete blockade — over 3234.58 ± 197.87 seconds, with a mean temperature of 31.5 ± 1.47°C at that time. The TOF count then progressed from 1 to 2 in 233.08 ± 72.26 seconds. In contrast, the non-perfused arms showed no decrease in TOF count during this period, but the temperature dropped to 30.13 ± 1.27°C. This difference in temperature between the two arms was statistically significant (P = 0.003, Table 3).

| Variables | Arms with a Tourniquet | Arms Without a Tourniquet | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of TOF 0 TO 1 (s) | TOF count remained 4 | 3234.58 ± 197.87 | - |

| Time of TOF 1 TO 2 (s) | TOF count remained 4 | 233.08 ± 72.26 | - |

| Temperature (˚C) | 30.13 ± 1.27 | 31.5 ± 1.47 | 0.003 |

Abbreviation: TOF, train-of-four.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered after inflation of the tourniquet.

In group B, where cisatracurium was administered before tourniquet inflation, the TOF count dropped to zero after 203.75 ± 22.52 seconds in the perfused arms, with a mean temperature of 33.81 ± 1.17°C during that period. Similarly, in the arms with restricted perfusion due to the tourniquet, the TOF count also reached zero after 204.58 ± 23.11 seconds (P = 0.82, Table 4). The mean temperature at that time was 33.88 ± 1.11°C. There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms in terms of temperature or TOF count (P = 0.58, Table 4).

| Variables | Arms with Tourniquet | Arms Without Tourniquet | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time that TOF count reached 0 (s) | 204.58 ± 23.11 | 203.75 ± 22.52 | 0.82 |

| Temperature (˚C) | 33.88 ± 1.11 | 33.81 ± 1.17 | 0.58 |

Abbreviation: TOF, train-of-four.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered before inflation of the tourniquet.

In the perfused arms, the TOF count increased from 0 to 1 over 3057.08 ± 175.77 seconds, and from 1 to 2 after an additional 217.75 ± 84.93 seconds (confidence interval: 95%). In contrast, these recovery times were prolonged to over 70 minutes in the arms with a tourniquet. The temperature during this period differed significantly between the two arms (P = 0.001) (confidence interval: 95%; Table 5).

| Variables | Arms with a Tourniquet | Arms Without a Tourniquet | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of TOF 0 TO 1 (s) | Over 70 min TOF count remained 0 | 3057.08 ± 175.77 | - |

| Time of TOF 1 TO 2 (s) | Over 70 min TOF count remained 0 | 217.75 ± 84.93 | - |

| Temperature (˚C) | 32.47 ± 1.34 | 33.53 ± 1.23 | 0.001 |

Abbreviation: TOF, train-of-four.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered before inflation of the tourniquet.

When comparing the two groups, the data showed that in arms without a tourniquet, the time for the TOF count to reach zero was 244.83 ± 64.53 seconds in group A and 203.75 ± 22.52 seconds in group B (P = 0.17). The time for the TOF count to return from 0 to 1 was 3234.58 ± 197.87 seconds in group A, compared to 3057.08 ± 175.77 seconds in group B (P = 0.13). The time for the TOF count to progress from 1 to 2 was 233.08 ± 72.26 seconds in group A versus 217.75 ± 84.93 seconds in group B (P = 0.74, Table 6).

Abbreviation: TOF, train-of-four.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Cis-atracurium administered after inflation of the tourniquet.

c Cis-atracurium administered before inflation of the tourniquet.

5. Discussion

We found that demographic factors such as age, sex, weight, height, BMI, and ideal body weight showed no significant differences between the two groups and did not influence the results. The data obtained from patient monitoring, including heart rate, blood pressure, and blood oxygen saturation, also revealed no differences, indicating that these factors did not affect the results.

In this study, we demonstrate that when the tourniquet is inflated and cisatracurium is administered, not only do the drugs fail to reach the neuromuscular junction, but the ischemia caused by the tourniquet also does not interfere with TOF monitoring. This suggests that neuromuscular monitoring can still be utilized during certain surgeries. However, many studies indicate that the use of a tourniquet and the duration of its inflation can influence the stimulation threshold in nerve monitoring during surgery (12).

Our study demonstrates that if neuromuscular monitoring is required during general anesthesia and surgery with a tourniquet, the tourniquet should be inflated before administering neuromuscular blocking agents (13). The results show that the TOF count returns from 0 to 1 after approximately 53 minutes, and from 0 to 2 after 57 minutes. To achieve further blockade, a maintenance dose of cisatracurium must be administered. Therefore, if excessive muscle paralysis is needed during surgery with a tourniquet, neuromuscular blocking agents should be administered after tourniquet deflation, or they can be infused with muscle relaxant drugs distal to the tourniquet, similar to intravenous local anesthesia (Bier block) (14).

Volatile anesthetic agents have a synergistic effect on neuromuscular blocking agents, and it seems that their use during anesthesia could enhance and prolong the effectiveness of neuromuscular blockade. This study demonstrates that complete cisatracurium-induced paralysis occurs within 3 to 5 minutes, suggesting that intubation should be performed after this period (15). In this study, when cisatracurium was administered before tourniquet inflation, complete blockade occurred in both arms within 3 to 4 minutes. Although this did not reach statistical significance, the duration of blockade in the tourniqueted arms was longer than in the perfused arms.

The data also revealed that the temperature in the perfused arms was higher than in the tourniqueted arm, with this difference being statistically significant. Cisatracurium is an intermediate-acting neuromuscular blocking agent whose elimination depends approximately 77% on temperature and pH through Hofmann elimination (2). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect a prolonged duration of neuromuscular blockade in limbs under a tourniquet, as both temperature and pH are reduced due to impaired perfusion. This leads to slower metabolism and elimination of the drug.

Although cisatracurium metabolism continues in tourniqueted limbs, it occurs at a reduced rate. Consequently, when the tourniquet is deflated, the redistribution of the drug into the systemic circulation is expected to have minimal neuromuscular blocking effect on other parts of the body. In a study conducted by Yildirim et al., it was demonstrated that when patients received either atracurium or vecuronium, the recovery time in the tourniqueted arms was longer than in the perfused arms in both groups. This prolongation was more pronounced in the group that received vecuronium, likely because vecuronium’s metabolism and elimination depend on hepatic and renal function. In the tourniqueted limb, the drug remains largely unmetabolized, and upon tourniquet deflation, it may affect TOF monitoring in other parts of the body (9).

It seems the neuromuscular blocking agents used in orthopedic surgery should be carefully considered for their pharmacodynamic effects, and they should be monitored during surgery and after the tourniquet is deflated. However, our study had several limitations. First, we specifically selected participants who had not undergone any surgical procedures on their upper limbs. This was intended to minimize potential adverse effects of tourniquet application, such as local pressure damage and ischemia. As a result, we limited the study duration to 70 minutes, which prevented us from accurately determining the onset and recovery times of neuromuscular blockade in these patients.

Another limitation was the small sample size, as this was a pilot study. Ethical considerations also played a role: It would have been unacceptable for a patient with healthy upper limbs to develop new complications related to our study after undergoing surgery elsewhere. Although we mitigated the risk by selecting healthy participants with smaller body sizes and minimizing tourniquet inflation time, safety concerns remain.

We recommend conducting future studies with a larger sample of patients undergoing limb surgery. In such studies, alternative techniques — such as the distal infusion of cisatracurium or other neuromuscular blocking agents beyond the tourniquet, similar to a Bier block — should be explored. These approaches could help clarify the systemic effects of these agents following tourniquet deflation.

5.1. Conclusions

Using a tourniquet during limb surgery can significantly affect the pharmacokinetics and effectiveness of neuromuscular blocking agents. Therefore, it is crucial for anesthesiologists to understand the intraoperative effects of tourniquet use and to work closely with the surgical team to determine the best timing for administering neuromuscular blockers. Inflating the tourniquet before anesthesia induction can cause significant discomfort and pain for the patient. To reduce this, it is preferable to inflate the tourniquet after giving sedatives and opioid analgesics, but before administering neuromuscular blocking agents. However, this order might lead to insufficient neuromuscular blockade in the isolated limb, which could complicate the surgical procedure.

Alternatively, if the tourniquet is inflated after administering the neuromuscular blocking agent, a complete blockade can occur in the isolated limb. In such cases, anesthesiologists must be cautious when deflating the tourniquet, as the sudden release may cause systemic redistribution of the drug from the isolated limb into the central circulation. This effect is especially significant in short-duration surgeries or when agents like atracurium or cisatracurium are used, both of which have temperature-dependent metabolism. Because limb temperature tends to decrease under tourniquet conditions, due to both exposure and restricted blood flow, drug metabolism may be impaired. For this reason, continuous neuromuscular monitoring, such as TOF stimulation, is strongly recommended throughout the procedure, especially after tourniquet deflation during recovery.

![The setup of acceleromyography with preload [Train-of-Four (TOF) Watch with Hand Adapter, Biometer, Odense, Denmark]: The piezoelectric acceleration transducer is placed in the hand adapter. The stretching wing ensures that the thumb does not touch the palm. The setup of acceleromyography with preload [Train-of-Four (TOF) Watch with Hand Adapter, Biometer, Odense, Denmark]: The piezoelectric acceleration transducer is placed in the hand adapter. The stretching wing ensures that the thumb does not touch the palm.](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/d53ab9a7e2e3b48b0e1a06b154f1aade67437a29/jcma-10-3-164383-g001-preview.webp)