1. Background

Cough, mucus hypersecretion, and airflow obstruction are well-documented consequences of cigarette smoking. These adverse effects are not limited to active smokers but are also observed in passive smokers (1). Studies have demonstrated that both active and passive smokers experience significantly more complications during the administration and recovery phases of anesthesia compared to non-smokers (2, 3). Coughing during emergence from general anesthesia (GA) occurs in approximately 40% to 76% of intubated cases (4). Peri-extubation coughing may result in significant complications, including increases in heart rate (HR) and BP, bronchospasm, intracerebral hemorrhage, raised intracranial pressure (ICP), elevated intraocular pressure, wound dehiscence after laparotomy, and cervical hematoma following thyroidectomy or carotid endarterectomy (5-7).

Several factors have been implicated in post-extubation coughing, including mechanical irritation from the laryngoscope blade, the endotracheal (ET) intubation technique, the endotracheal tube (ETT) cuff and its size, straining during extubation, accumulated secretions, and smoking (8). Various strategies have been employed to minimize emergence-related coughing. These include the use of a laryngeal mask airway, performing deep extubation, and administering systemic agents such as tramadol, short-acting opioids, ketamine, and dexmedetomidine (DEX). Additionally, local anesthetics and corticosteroids applied near the tracheal tube cuff have shown efficacy in reducing airway irritation (9, 10).

Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective α2-adrenoreceptor agonist, possesses anxiolytic, sedative, analgesic, and amnestic effects. It also exerts sympatholytic effects by lowering systemic norepinephrine levels, thereby reducing BP and HR. Furthermore, it may suppress coughing by inhibiting C-fiber-mediated bronchial contractions, a mechanism thought to contribute to its antitussive effect (11).

Magnesium is an essential ion involved in numerous physiological processes in the heart, brain, and skeletal muscles. Its smooth muscle-relaxant, spasmolytic, and anti-inflammatory properties contribute to reduced coughing, bronchial irritation, and bronchospasm during emergence from anesthesia (12).

2. Objectives

This investigation aims to compare the effectiveness of DEX and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) in suppressing emergence coughing in smokers, while also evaluating their effects on hemodynamic stability and sedation.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Population

This randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical investigation was conducted at Ain Shams University hospitals in Cairo, Egypt, between July 2022 and August 2023. Prior to study initiation, ethical approval was secured from the REC of the Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University (approval No.: FMASU MD 61/2022). Additionally, the trial was prospectively registered with PACTR under registration number PACTR202308591985746 on August 17, 2023. Written informed consent was secured from all participants before enrollment. A total of 165 adult cases who were scheduled to undergo elective open abdominal surgeries, including procedures such as hernia repair and appendectomy, were recruited upon confirmation of eligibility.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants were adults (18 - 60 years) with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-II (13), who were active smokers (≥ 1 pack/day for ≥ 1 year); passive smokers were excluded. Patients were ineligible if they had pulmonary disease (asthma, interstitial fibrosis, chronic cough), were taking sedatives, antitussives, or ACE inhibitors, had a difficult airway, or contraindications to MgSO4 or DEX (allergy, bradyarrhythmias). Those with chronic renal failure (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) were also excluded due to magnesium’s renal clearance. Because magnesium potentiates rocuronium, neuromuscular recovery was closely monitored before extubation; no delays were observed, though a rescue plan was prepared.

3.3. Randomization and Blinding

After eligibility confirmation and consent, cases were randomly assigned to one of three equal groups (n = 55 each) using a computer-generated randomization sequence. The groups included the MgSO4 group (group M), the DEX group (group D), and controls (group C). To maintain allocation concealment, assignments were enclosed in opaque, sealed envelopes that were not accessible until the point of intervention. A single designated investigator, who was responsible for preparing the study drugs and not involved in case care or outcome assessment, unsealed the envelopes. Both the attending anesthesiologist and the outcome assessor were blinded to group allocation. To ensure blinding, study drugs were diluted to identical volumes (100 mL) of normal saline (NS) with indistinguishable appearance and infused over 10 minutes. Outcome assessors and attending anesthesiologists were independent and unaware of group allocation.

3.4. Anesthetic Management

Preoperative assessment included a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and laboratory investigations comprising CBC, liver and kidney function tests, and coagulation profile. An ECG was performed for cases over 40 years of age. All cases fasted for at least eight hours before surgery. Upon arrival in the operating room, standard ASA monitoring was instituted, including non-invasive BP (NIBP), ECG, pulse oximetry (SpO2), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2). After IV cannulation, Ringer’s acetate was given at 10 mL/kg. Anesthesia was induced after three minutes of preoxygenation using IV fentanyl 2 µg/kg, propofol 2 mg/kg, and rocuronium 0.5 mg/kg to facilitate ET intubation with an appropriately sized tube. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane at a concentration of 2 - 3% in a closed-circuit system with 50% oxygen. Mechanical ventilation parameters were adjusted to maintain ETCO2 between 32 and 38 mmHg. All cases received 1 g of IV paracetamol and 4 mg of ondansetron as antiemetic prophylaxis.

During subcutaneous tissue closure, cases in group M were administered 30 mg/kg of MgSO4 diluted in 100 mL of NS intravenously over a 10-minute period. The group D received 0.5 µg/kg of DEX prepared in 100 mL of NS, also infused over 10 minutes. In contrast, group C was given an equivalent volume of NS over the same duration. Concurrently, the sevoflurane concentration was adjusted to 1% and subsequently discontinued at the conclusion of the surgical procedure.

Reversal of neuromuscular blockade was achieved using neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and atropine 0.02 mg/kg. Emergence was facilitated by gentle stimulation such as verbal commands and sternal rubs. Extubation was performed once cases regained consciousness, demonstrated adequate spontaneous ventilation with sufficient tidal volume, and showed signs of neuromuscular recovery. Following extubation, all cases received 100% oxygen via face mask for five minutes. In cases of bradycardia (HR < 50 bpm) during or after DEX infusion, atropine 0.5 mg IV was planned as first-line management, and infusion would be discontinued if bradycardia persisted. No patient required discontinuation of infusion.

3.5. Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes encompassed the severity and frequency of coughing during emergence, evaluated from discontinuation of the inhalational agent to ten minutes post-extubation. Cough severity was rated using a standardized 4-point scale: Zero indicated no cough, 1 indicated a single cough with SpO2 ≥ 95%, 2 denoted multiple coughs with SpO2 ≥ 95%, 3 indicated multiple coughs with SpO2 < 95%, and 4 denoted severe coughing with SpO2 < 95% requiring IV medication. This evaluation was conducted by an independent anesthesiologist blinded to group allocation.

Secondary outcomes encompassed variations in hemodynamic measures and assessment of sedation levels. Hemodynamic monitoring included HR, assessed via continuous ECG, and mean arterial pressure (MAP), measured using NIBP monitoring. Both parameters were recorded every five minutes starting from the time of study drug infusion until 30 minutes post-extubation. Sedation was assessed at 30 minutes post-extubation using the Ramsay Sedation Score, which ranges from 1 (anxious or agitated) to 6 (no response to external stimuli) (14).

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size estimation was conducted based on data derived from the study by Hur et al. (15), who reported an effect size of 0.24 when comparing magnesium infusion with placebo for reducing the incidence of cough during anesthetic emergence. Assuming a moderate effect size and employing a one-way ANOVA for three groups, a total sample of 165 cases (55 cases per group) was determined to be sufficient to achieve 80% statistical power (β = 0.20) at a 0.05 level of significance (α = 0.05).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software package (SPSS for Windows®, Version 16.0, Chicago, SPSS Inc.) after the data had been meticulously collected, coded, and organized. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (Q1 - Q3), while categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. For post hoc analysis, Tukey’s HSD, Fisher’s exact test, and Mann-Whitney U test were applied where appropriate. Depending on data distribution, one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for numerical variables, while categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons, with significance set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

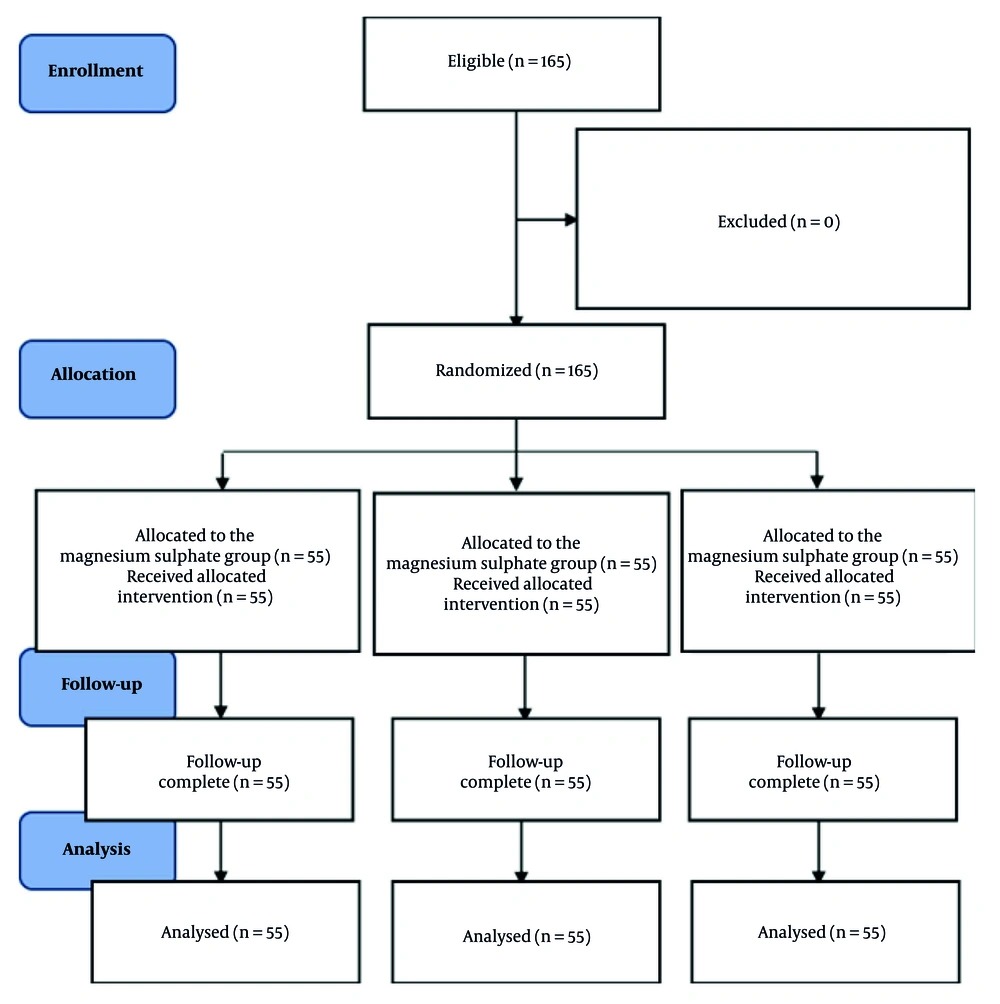

A total of 165 cases were enrolled in this investigation, all of whom completed the protocol without any exclusions (Figure 1).

The baseline demographic characteristics were comparable among the three study groups. No substantial variations were found in terms of age (P = 0.771), sex distribution (P = 0.912), body weight (P = 0.462), Body Mass Index (BMI; P = 0.298), smoking quantity in packs per day (P = 0.826), or type of surgical procedure performed (P = 0.511, Table 1).

| Variables | Group C (N = 55) | Group D (N = 55) | Group M (N = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 40.62 ± 10.66 | 41.58 ± 11.50 | 42.15 ± 11.52 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 40 (72.7) | 39 (70.9) | 41 (74.5) |

| Female | 15 (27.3) | 16 (29.1) | 14 (25.5) |

| Height (cm) | 176.91 ± 18.26 | 180.62 ± 20.14 | 179.64 ± 19.92 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.56 ± 13.39 | 85.14 ± 15.68 | 83.41 ± 16.51 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.42 ± 2.08 | 31.74 ± 3.56 | 31.05 ± 1.84 |

| Smoking (Pack/d) | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 1.38 ± 0.21 |

| Surgery | |||

| Appendectomy | 25 (45.5) | 26 (47.3) | 24 (43.6) |

| Hernioplasty | 23 (41.8) | 22 (40.0) | 25 (45.5) |

| Partial colectomy | 5 (9.1) | 4 (7.3) | 5 (9.1) |

| Splenoctomy | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.5) | 1 (1.8) |

Abbreviations: Group C, control group; group M, magnesium sulfate group; group D, dexmedetomidine group; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Baseline characteristics are presented descriptively.

c No statistical testing was performed in accordance with CONSORT guidelines.

With respect to coughing severity during emergence from anesthesia, both the group D and group M demonstrated significantly lower cough severity scores relative to group C, with P-values of < 0.001 and 0.003, respectively. Furthermore, cough severity in group D was substantially lower than in group M (P < 0.001). Similarly, the incidence of coughing was significantly reduced in groups D and M relative to group C (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively), and a substantially lower incidence was also observed in group D compared to group M (P = 0.002, Table 2).

Abbreviations: Group C, control group; group M, magnesium sulfate group; group D, dexmedetomidine group; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

a Significantly lower than the other two groups.

b Significantly lower than group C.

c Statistically significant < 0.05.

No substantial variations were observed in baseline hemodynamic parameters among the three groups. Specifically, both HR and MAP measured five minutes before drug infusion were comparable across group C, group D, and group M, with P = 0.671 for HR and P = 0.768 for MAP (Table 3).

| Variables (min) | Group C (N = 55) | Group D (N = 55) | Group M (N = 55) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | ||||

| HR 5 before drug infusion | 89.59 ± 9.26 | 86.43 ± 12.84 | 88.61 ± 10.51 | 0.671 |

| HR 5 after drug infusion | 91.25 ± 11.06 | 78.20 b ± 10.44 | 87.15 ± 11.11 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 5 after extubation | 117.78 ± 8.77 | 83.65 b ± 16.57 | 105.45 c ± 17.81 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 10 | 113.2 ± 8.14 | 79.04 b ± 18.23 | 102.4 c ± 16.63 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 15 | 107.64 ± 8.08 | 78.22 b ± 16.56 | 96.84 c ± 14.84 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 20 | 103.69 ± 8.74 | 77.04 b ± 15.64 | 94.51 c ± 14.40 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 25 | 101.0 ± 7.42 | 77.78 b ± 14.06 | 91.95 c ± 12.79 | < 0.001 d |

| HR 30 | 98.38 ± 6.91 | 78.27 b ± 14.58 | 90.33 c ± 11.71 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||

| MAP 5 before drug infusion | 81.26 ± 8.43 | 80.34 ± 13.84 | 80.89 ± 12.38 | 0.768 |

| MAP 5 after drug infusion | 89.49 ± 11.63 | 82.8 b ± 15.97 | 100.8 ± 17.33 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 5 after extubation | 114.53 ± 10.24 | 81.45 b ± 15.89 | 100.42 c ± 17.12 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 10 | 110.84 ± 8.31 | 79.16 b ± 16.01 | 97.45 c ± 16.95 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 15 | 104.33 ± 7.72 | 76.75 b ± 15.15 | 95.22 c ± 17.29 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 20 | 101.80 ± 7.46 | 76.25 b ± 14.91 | 94.42 c ± 14.64 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 25 | 97.93 ± 7.75 | 76.64 b ± 13.08 | 92.51 c ± 13.08 | < 0.001 d |

| MAP 30 | 98.02 ± 8.81 | 79.29 b ± 12.72 | 90.95 c ± 12.54 | < 0.001 d |

| Degree of sedation [median (Q1 - Q3)] | 1 (1 - 1) | 2 (1 - 3) | 1 (1 - 2) | < 0.001 d |

Abbreviations: Group C, control group; group M, magnesium sulfate group; group D, dexmedetomidine group; HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per minute; MAP, mean arterial pressure; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

b Significantly lower than the other two groups.

c Significantly lower than group C.

d Statistically significant < 0.05.

Following drug administration, group D exhibited a substantial reduction in both HR and MAP beginning five minutes post-infusion and continuing throughout the entire 30-minute observation period, with P < 0.001 at all subsequent time points. In contrast, group M demonstrated a delayed but statistically significant decline in HR and MAP starting five minutes after extubation, also persisting through to the 30-minute mark, compared to group C (P < 0.001 for all post-extubation measurements; Table 3).

The level of sedation, determined using the Ramsay Sedation Score, was substantially higher in both group D and group M relative to controls [median (Q1 - Q3): 2 (1 - 3) and 1 (1 - 2), respectively, versus 1 (1 - 1); P < 0.001]. Moreover, group D showed markedly deeper sedation relative to group M (P < 0.001), indicating a more pronounced sedative effect of DEX (Table 3).

5. Discussion

Emergence from GA is often associated with adverse responses, such as coughing, elevated HR, and increased BP (16). In the present study, both DEX and MgSO4 were found to be effective in reducing the intensity and frequency of emergence cough compared to saline controls. When comparing the MgSO4 group to controls, HR and MAP were markedly reduced starting five minutes post-extubation, accompanied by a higher degree of sedation.

Several mechanisms may explain the cough-suppressing effects of MgSO4. These include its bronchodilatory properties via inhibition of cholinergic neuromuscular transmission, anti-inflammatory effects, NMDA receptor blockade in lungs and airways, and its ability to inhibit calcium-mediated smooth muscle contraction. Additionally, magnesium reduces endplate potential magnitude and decreases muscle fiber excitability by acting as a calcium channel blocker at presynaptic nerve terminals, thereby limiting acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction (17, 18).

Our findings harmonize with those reported by Deshpande et al. (19), who documented that DEX significantly suppressed emergence cough in cases undergoing mastoidectomy. However, contrary to our results, their study showed no significant antitussive effect with 30 mg/kg of MgSO4.

Similarly, studies by Rashmi et al. (20) and Tandon and Goyal (21) also concluded that DEX was more effective than MgSO4 in preventing emergence cough. Further support comes from investigations by Guler et al. (22) and Mistry et al. (23), who found that DEX at doses of 0.5 µg/kg and 0.3 µg/kg, respectively, substantially reduced cough incidence upon emergence from anesthesia. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Tung et al. (4), including 70 studies, demonstrated that DEX, fentanyl, remifentanil, IV lidocaine, intracuff lidocaine, and topical lidocaine all reduced moderate to severe peri-extubation coughing. Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) analysis ranked DEX as the most effective agent in reducing moderate to severe coughing.

Although DEX provided earlier and more profound hemodynamic stability, MgSO4’s delayed attenuation of HR and MAP after extubation may be advantageous in patients where sedation is undesirable, such as in ambulatory settings or patients requiring early postoperative neurological assessment. Therefore, MgSO4 offers a safer alternative for attenuating stress responses while minimizing the sedative burden.

Regarding MgSO4, our findings concur with a study by Hur et al. (15), which reported a reduction in cough severity following one-lung ventilation. However, in contrast to our study, MgSO4 did not reduce the overall incidence of coughing.

Jafarzadeh et al. (24) reported no substantial variation between DEX and MgSO4 in suppressing emergence cough, which differs from our findings. In another contrasting report, Kim et al. (25) found that DEX, administered as a 0.4 µg/kg/h infusion from induction to extubation, did not reduce coughing. This discrepancy may be explained by the use of desflurane for maintenance anesthesia, a volatile agent correlated with a high incidence of coughing (26).

Dexmedetomidine attenuates the stress response and stabilizes hemodynamics by activating central α2-receptors in the vasomotor center of the brainstem, resulting in reduced norepinephrine release, bradycardia, and hypotension (20). Sedation is achieved through parasympathetic activation and suppression of sympathetic tone originating from the locus coeruleus (27).

Magnesium sulfate exerts its hemodynamic effects via calcium channel antagonism, direct vasodilation, and inhibition of catecholamine release through sympathetic ganglion blockade, resulting in reduced arterial pressure. It also depresses sinus node activity and prolongs atrioventricular nodal refractoriness (19, 28). Its sedative effects stem from NMDA receptor inhibition — blocking the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS — which also decreases the requirement for sedative-hypnotic agents during GA (17, 29).

Although sedation is often considered an undesirable side effect due to its potential to delay recovery and prolong post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) stays, the sedation levels associated with both DEX and MgSO4 in this study were not sufficient to delay recovery or case transfer from PACU. Our findings regarding hemodynamic responses and sedation levels during emergence are consistent with those documented by Rashmi et al. (20), Deshpande et al. (19), and Jafarzadeh et al. (24). Similarly, Choudhary et al. (30) observed greater sedation in the DEX group relative to MgSO4, and greater sedation in the MgSO4 group relative to controls.

Concerning hemodynamic effects, Khadke and Gopal Agrawal (31) found that IV MgSO4 provided better hemodynamic stability than esmolol during emergence from GA. Likewise, Marashi et al. (14) reported that cases in the NS group exhibited higher levels of responsiveness and alertness post-extubation relative to those in the MgSO4 group. However, Tandon and Goyal (21) found no substantial variation in hemodynamic attenuation between DEX and MgSO4 groups, in contrast to our results.

5.1. Conclusions

Dexmedetomidine demonstrated superior performance in cough suppression, hemodynamic control, and sedation depth, without delaying postoperative recovery. Magnesium sulfate also provided considerable benefit, particularly in reducing airway irritation and stabilizing post-extubation hemodynamics.

5.2. Limitations

This study has limitations. Neuromuscular monitoring was not employed, despite the potential of MgSO4 to potentiate non-depolarizing muscle relaxants; however, no clinically significant recovery delays were observed. The trial was registered with PACTR (No. PACTR202308591985746) on August 17, 2023, after enrollment began, making delayed registration another limitation.

5.3. Future Studies

Future studies should incorporate quantitative neuromuscular monitoring to objectively assess this effect.