1. Background

Worldwide, more than 800,000 coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgeries are performed annually (1). The CABG surgery is traditionally conducted via median sternotomy, a procedure that can cause damage to both bone and soft tissues. Pain levels are particularly high during the first days following cardiac surgery (2). Between 30% and 75% of patients report moderate to severe chronic pain after cardiac surgery (3), and it is known that 4% to 10% develop chronic pain syndrome associated with sternotomy (4).

Traditionally, opioid-based analgesics have been the primary method for postoperative pain control in cardiac surgeries for many years (5). However, high-dose opioid use is associated with numerous side effects, including sedation, respiratory depression, delayed extubation, urinary retention, itching, nausea, and vomiting (6). Additionally, intravenous opioid therapy is commonly preferred for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (7).

Thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) is a method capable of providing excellent “opioid-free” analgesia following cardiac surgery. The TEA has been recognized as an effective alternative due to its ability to reduce respiratory complications, arrhythmias, and mortality rates (8).

Regional anesthesia, as an essential component of multimodal analgesia approaches, allows cardiac anesthesiologists to minimize opioid consumption (9). Thoracic epidural and paravertebral blocks are effective methods for continuous pain management; however, their widespread use in cardiac surgery patients is restricted due to the increased risk of epidural hematoma, particularly after cardiac surgery, where coagulopathy, anticoagulation, and antiplatelet drug use are prevalent (10). Perioperative analgesic management has become a crucial component of fast-track cardiac anesthesia practices, with the potential to facilitate early tracheal extubation and shorter hospital stays (11). However, cases where existing pain control methods are insufficient are still observed (7). In such patients, the use of intravenous opioids during the intraoperative and postoperative periods may lead to undesirable effects such as nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, and sedation (12).

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the effects of the block technique, implemented without any modifications to the existing clinical protocols in our institution, on postoperative recovery. Specifically, the effects of extubation time on parameters related to respiratory adequacy and pain control during the post-anesthesia period were investigated.

3. Methods

3.1. Trial Design and Ethical Approval

This study was designed as a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. It was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aydın Adnan Menderes University (approval date: January 16, 2020; Decision No: 97479326-050.04.04) and conducted between February 1, 2020, and February 1, 2021. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06893601). Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion.

3.2. Participants

A total of 80 patients, aged 30 - 80 years, scheduled for elective CABG surgery with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status III-IV were enrolled. Exclusion criteria were: Hypersensitivity to study drugs, off-pump CABG, chronic opioid use, severe psychiatric illness, inability to provide consent, infection at the injection site, preoperative LVEF < 30%, prior sternotomy, severe renal or liver disease, and communication difficulties.

3.3. Randomization and Blinding

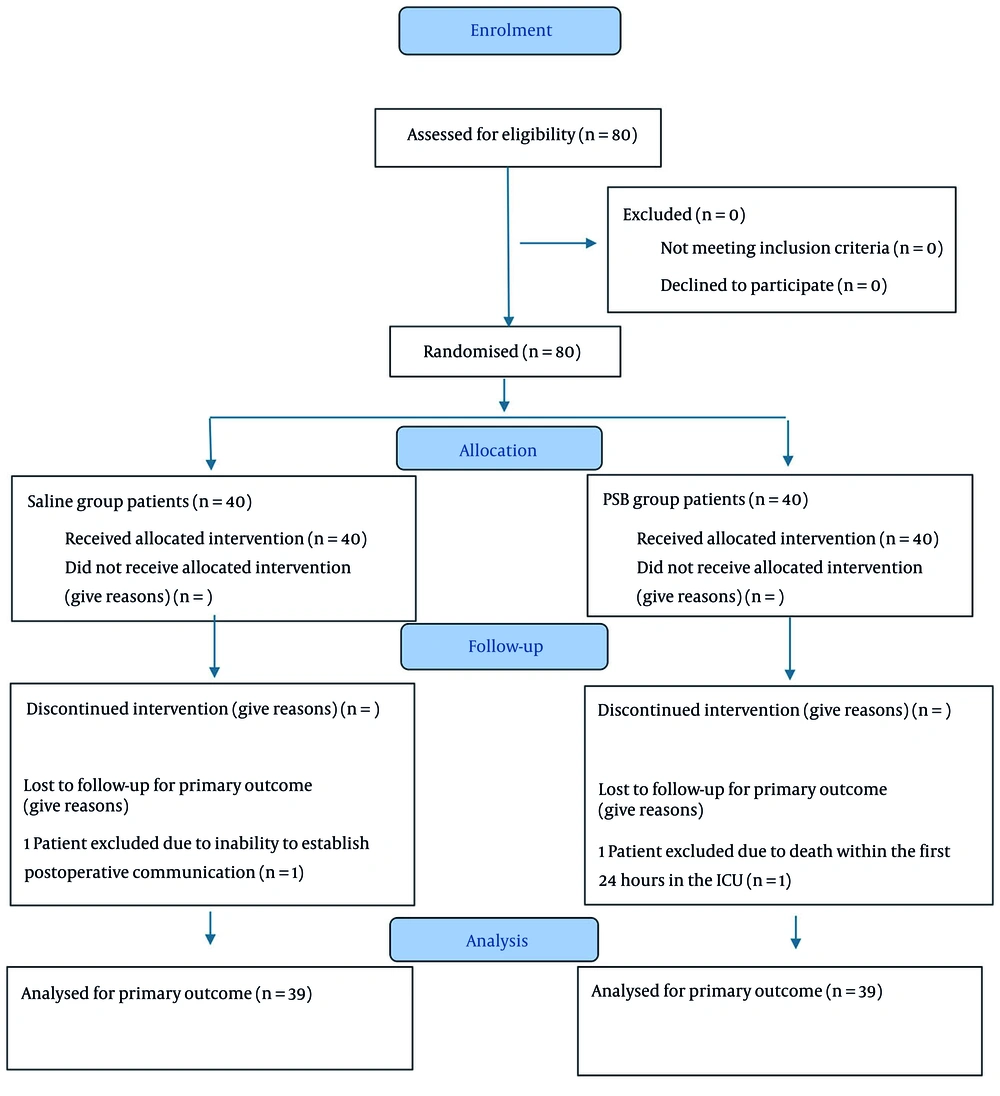

No sample size estimation was performed prior to the initiation of the study. The enrolled patients (n = 80) were randomized into two groups using a computer-generated random number table. Group assignments were carried out using sealed envelopes prepared by an independent researcher who was not involved in the study, thereby ensuring blinding of both investigators and patients. The syringes containing either bupivacaine or saline were prepared by an independent anesthesiologist not involved in the study, ensuring that both the patients and the outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation. Patients were randomly allocated to one of two groups: The parasternal block (PSB) group (n = 40) or the saline group (n = 40). All randomized patients received the allocated intervention, and none failed to undergo the assigned treatment.

3.3.1. Follow-up Phase

During follow-up, one patient from each group was excluded from the final analysis. In the saline group, one patient was excluded due to the inability to establish postoperative communication, which precluded assessment of the primary outcome. In the PSB group, one patient died within the first 24 hours in the intensive care unit (ICU) and was therefore excluded.

3.3.2. Analysis Phase

Consequently, a total of 78 patients were included in the primary outcome analysis: Thirty-nine in the saline group and 39 in the PSB group. There were no cases of non-receipt of treatment in either group, and treatment discontinuation occurred in only one patient per group (Figure 1).

3.4. Interventions

3.4.1. Anesthesia Management

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics [age, sex, Body Mass Index (BMI), comorbidities, ASA physical status] were recorded. Monitoring included 5-lead ECG, invasive arterial pressure, pulse oximetry, and central venous pressure. A standard anesthesia protocol was applied: Induction with propofol (1 - 1.5 mg/kg), midazolam (0.03 - 0.05 mg/kg), fentanyl (3 - 4 µg/kg), lidocaine (1 mg/kg), and rocuronium (1 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (1.5 - 2%) in 50/50 O2/air. Central venous access was achieved with ultrasound-guided catheterization. Heparinization (300 - 400 U/kg) was titrated to achieve an ACT > 480 s and was reversed with protamine after anastomosis.

3.4.2. Parasternal Block Procedure

At the end of surgery, prior to sternotomy closure, patients in the PSB group received bilateral parasternal injections of 2 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine into the 2nd - 6th intercostal spaces on each side (total 20 mL). In the saline group, the same procedure was performed with 0.9% NaCl. No local anesthetic was applied around thoracic tube sites.

3.5. Postoperative Management

Paracetamol doses routinely administered every eight hours were not recorded for either group. However, the timing of the first tramadol dose and the total tramadol doses administered were documented from the ICU monitoring charts. Extubation time was defined as the duration between the patient’s admission to the ICU and the removal of the endotracheal tube. After extubation, patients’ Triflo exercise performance, specifically the level of ball elevation (level 1, 2, 3, or 4), was recorded at the 1st, 4th, and 12th hours. Routine postoperative parameters, including heart rate, cardiac rhythm, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), blood pressure, and arterial blood gas levels, were recorded. ICU length of stay and ward length of stay were also documented. Patient satisfaction was assessed in the first postoperative month using the Short Form-36 (SF-36), and the collected data were statistically analyzed.

Following surgery, patients were transferred intubated to the ICU. In the ICU, respiratory support was provided in the pressure-controlled synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) mode. Continuous monitoring included ECG, SpO2, invasive arterial pressure, and central venous pressure. Patient management in the ICU, including extubation, analgesic administration, and transfer to the ward, followed standard institutional protocols.

Pain assessment was performed by the ICU nurse responsible for each patient. Assessment commenced upon ICU admission and was conducted using the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) at the 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 8th hours while patients remained intubated. After extubation, pain was evaluated with the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) at the 1st, 4th, and 12th hours. If BPS or NRS scores were ≥ 4 despite the routine administration of 1,000 mg paracetamol every eight hours, intravenous tramadol (0.5 - 1 mg/kg) was administered.

Although routine paracetamol doses were not recorded, the timing of the first tramadol administration and the total tramadol consumption were documented from ICU monitoring charts. Extubation time was defined as the interval between ICU admission and removal of the endotracheal tube. Following extubation, patients’ respiratory performance was assessed using Triflo spirometry, recording the level of ball elevation (levels 1 - 4) at the 1st, 4th, and 12th hours. Routine postoperative parameters, including heart rate, cardiac rhythm, SpO2, blood pressure, and arterial blood gas values, were also documented. The ICU and ward lengths of stay were recorded. Patient satisfaction was evaluated at one month postoperatively using the SF-36.

3.6. Outcomes

- Primary outcome: Extubation time (h).

- Secondary outcomes: Postoperative pain scores, total tramadol consumption, time to first tramadol administration, ICU stay, hospital stay, Triflo exercise performance, and patient satisfaction (SF-36).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, California). An independent samples t-test was used for variables with a normal distribution. The Pearson chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical data. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

4. Results

A total of 80 patients were included in this study; however, one patient from both the saline group and the PSB group was excluded during intraoperative and postoperative follow-ups. Therefore, the statistical analysis was conducted based on 78 patients (Figure 1).

4.1. Demographic Data

No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in terms of age, weight, height, BMI, gender, ASA physical status, or comorbidities (Table 1).

| Demographic Characteristics | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61.95 ± 10.28 | 63.32 ± 7.83 | 0.513 |

| Height (cm) | 167.87 ± 8.97 | 169.15 ± 6.89 | 0.070 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.15 ± 13.06 | 78.18 ± 12.81 | 0.991 |

| BMI | 27.78 ± 4.45 | 27.34 ± 4.26 | 0.658 |

| Gender | 0.544 | ||

| Female | 8 | 7 | |

| Male | 31 | 32 | |

| ASA score | 0.513 | ||

| 3 | 38 | 38 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Comorbidities | 0.060 | ||

| No | 8 | 7 | |

| DM | 3 | 2 | |

| HT | 8 | 7 | |

| DM + HT | 20 | 19 |

Abbreviations: PSB, parasternal block; BMI, Body Mass Index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No.

4.2. Surgical and Intensive Care Unit Durations

No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of surgical duration, cross-clamp time, ICU stay, or ward stay durations (Table 2). However, the extubation times in the PSB group were found to be significantly shorter than those in the saline group (PSB group: 8.76 ± 3.28 hours; saline group: 14.76 ± 5.20 hours, P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Variables | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical duration (min) | 304.37 ± 52.33 | 306.31 ± 49.39 | 0.663 |

| Cross-clamp duration (min) | 53.82 ± 16.87 | 52.13 ± 18.94 | 0.325 |

| Extubation time (h) | 14.76 ± 5.20 | 8.76 ± 3.28 | < 0.001 |

| ICU stay duration (h) | 67.95 ± 15.9 | 65.92 ± 16.05 | 0.548 |

| Ward stay duration (h) | 83.65 ± 16.28 | 82.23 ± 17.43 | 0.783 |

| Postoperative total tramadol amount (mg) | 212.5 ± 82.23 | 150 ± 64.72 | < 0.001 |

| Time to first tramadol administration in ICU (h) | 12.35 ± 5.75 | 17.26 ± 4.78 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: PSB, parasternal block; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.3. Time of First Analgesic Requirement

The time of the first rescue analgesic (tramadol) administration was found to be significantly earlier in the saline group than in the PSB group (saline group: 12.35 ± 5.75 hours; PSB group: 17.26 ± 4.78 hours, P < 0.001; Table 2).

4.4. Total Tramadol Consumption

The total amount of tramadol used during the postoperative period was found to be significantly higher in the saline group than in the PSB group (saline group: 212.5 ± 82.23 mg; PSB group: 150 ± 64.72 mg, P < 0.001; Table 2).

4.5. Pain Assessment Scales

4.5.1. Behavioral Pain Scale While Intubated

No significant differences were observed between the groups during the early hours (1st, 2nd, and 4th hours). However, at the 8th hour, pain scores in the PSB group were found to be significantly lower than those in the saline group (P = 0.001, Table 3).

| Scales | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPS | |||

| 1st hour | 3 ± 0 | 3 ± 0 | - |

| 2nd hour | 3 ± 0 | 3 ± 0 | - |

| 4th hour | 3.18 ± 0.68 | 3 ± 0 | 0.109 |

| 8th hour | 3.76 ± 1.21 | 3 ± 0 | < 0.001 |

| Numeric Pain Scale | |||

| 1st hour | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 2 ± 1.37 | 0.245 |

| 4th hour | 2.79 ± 1.25 | 1.97 ± 1.03 | 0.024 |

| 12th hour | 3.23 ± 1.12 | 2.26 ± 0.89 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: PSB, parasternal block; BPS, Behavioral Pain Scale.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.5.2. Numeric Rating Scale After Extubation

No differences were detected between the groups at the 1st hour after extubation, but pain scores at the 4th and 12th hours in the PSB group were significantly lower than those in the saline group (P = 0.024 and P < 0.001, respectively; Table 3).

4.6. Hemodynamic and Respiratory Parameters

4.6.1. Heart Rate, Blood Pressure, and Oxygen Saturation

No significant differences were observed between the groups at the 0th, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 8th, 12th, and 24th-hour measurements. However, at the 1st hour, systolic blood pressure in the PSB group was significantly higher than in the saline group (P = 0.028), although this difference was not considered clinically significant (Table 4).

| Parameters; Time (h) | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | |||

| 0 | 99.58 ± 17.68 | 93.03 ± 18.27 | 0.112 |

| 1 | 98.23 ± 17.77 | 92.79 ± 16.26 | 0.163 |

| 2 | 99.33 ± 18.63 | 95.05 ± 16.28 | 0.285 |

| 3 | 100.45 ± 16.68 | 96.58 ± 16.24 | 0.303 |

| 4 | 101.48 ± 16.9 | 96.47 ± 17.41 | 0.202 |

| 8 | 95.95 ± 17.7 | 96.58 ± 16.64 | 0.872 |

| 12 | 94.33 ± 18.2 | 95.92 ± 14.68 | 0.672 |

| 24 | 98.88 ± 12.83 | 94.05 ± 10.93 | 0.079 |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| 0 | 115.4 ± 28.02 | 116.13 ± 25.14 | 0.904 |

| 1 | 115.43 ± 15.11 | 125.16 ± 22.29 | 0.028 |

| 2 | 115.18 ± 15.2 | 116.39 ± 15.74 | 0.729 |

| 3 | 111.85 ± 15.36 | 112.32 ± 15.31 | 0.894 |

| 4 | 109.75 ± 15.03 | 111.05 ± 14.64 | 0.700 |

| 8 | 113.53 ± 16.72 | 118.76 ± 12.29 | 0.121 |

| 12 | 115.5 ± 16.96 | 116.84 ± 13.29 | 0.699 |

| 24 | 116.2 ± 16.16 | 117.82 ± 12.75 | 0.627 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||

| 0 | 58.65 ± 14.02 | 57.87 ± 12.69 | 0.797 |

| 1 | 57.3 ± 9.36 | 61.11 ± 9.59 | 0.080 |

| 2 | 59.45 ± 8.27 | 58.79 ± 8.88 | 0.735 |

| 3 | 58.45 ± 6.69 | 56.89 ± 8.3 | 0.364 |

| 4 | 58.03 ± 8.19 | 57.11 ± 9.02 | 0.638 |

| 8 | 58.25 ± 7.9 | 58.05 ± 8.06 | 0.913 |

| 12 | 57.8 ± 7.37 | 57.5 ± 8.96 | 0.872 |

| 24 | 57.4 ± 7.76 | 58.34 ± 7.99 | 0.599 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation | |||

| 0 | 98.3 ± 2.29 | 99.18 ± 1.33 | 0.040 |

| 1 | 98.53 ± 1.96 | 99.26 ± 1.27 | 0.053 |

| 2 | 99.03 ± 1.05 | 99.03 ± 1.3 | 0.996 |

| 3 | 98.93 ± 1.14 | 99.18 ± 1.31 | 0.354 |

| 4 | 98.63 ± 1.19 | 99.05 ± 1.43 | 0.155 |

| 8 | 97.93 ± 1.85 | 100.87 ± 16.46 | 0.265 |

| 12 | 97.58 ± 2.21 | 97.68 ± 1.86 | 0.814 |

| 24 | 96.73 ± 2.49 | 97.63 ± 1.99 | 0.079 |

Abbreviation: PSB, parasternal block.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.6.2. The pH Levels

At the 8th hour, the pH level in the PSB group was significantly lower than in the saline group (P = 0.050). No significant differences were observed at other time points (Table 5).

| Variables | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Triflo | |||||||||

| Postoperative 1st hour | 37 (92.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (86.8) | 5 (13.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.476 |

| Postoperative 4th hour | 16 (40) | 23 (57.5) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (28.9) | 25 (65.8) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0.551 |

| Postoperative 12th hour | 1 (2.5) | 15 (37.5) | 24 (60) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (26.3) | 28 (73.7) | 0 (0) | 0.274 |

| pH | |||||||||

| 0th hour | 7.58 ± 1.37 | 7.38 ± 0.08 | 0.371 | ||||||

| 1st hour | 7.38 ± 0.09 | 7.39 ± 0.09 | 0.498 | ||||||

| 2nd hour | 7.37 ± 0.07 | 7.38 ± 0.08 | 0.624 | ||||||

| 3rd hour | 7.38 ± 0.06 | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 0.397 | ||||||

| 4th hour | 7.40 ± 0.06 | 7.40 ± 0.07 | 0.895 | ||||||

| 8th hour | 7.42 ± 0.05 | 7.40 ± 0.04 | 0.050 | ||||||

| 12th hour | 7.43 ± 0.06 | 7.42 ± 0.05 | 0.321 | ||||||

| 24th hour | 7.43 ± 0.04 | 7.44 ± 0.06 | 0.445 | ||||||

| Partial arterial oxygen pressure | |||||||||

| 0th hour | 148.4 ± 71.04 | 170.05 ± 84.76 | 0.224 | ||||||

| 1st hour | 129.55 ± 68.42 | 130.82 ± 62.8 | 0.932 | ||||||

| 2nd hour | 117.68 ± 60.38 | 130.42 ± 49.23 | 0.312 | ||||||

| 3rd hour | 116.9 ± 29.33 | 128.74 ± 23.71 | 0.054 | ||||||

| 4th hour | 115.23 ± 28.43 | 121.03 ± 22.65 | 0.324 | ||||||

| 8th hour | 108.75 ± 29.27 | 122.21 ± 24.72 | 0.032 | ||||||

| 12th hour | 105.05 ± 25.79 | 114.66 ± 30.77 | 0.138 | ||||||

| 24th hour | 93.98 ± 23.51 | 101.39 ± 21.72 | 0.152 | ||||||

| Partial arterial carbon dioxide pressure | |||||||||

| 0th hour | 40.95 ± 7.52 | 40.26 ± 11.42 | 0.753 | ||||||

| 1st hour | 39.88 ± 9.36 | 38.26 ± 9.47 | 0.452 | ||||||

| 2nd hour | 38.05 ± 11.11 | 37.95 ± 6.88 | 0.961 | ||||||

| 3rd hour | 39.15 ± 9.64 | 37.87 ± 7.36 | 0.513 | ||||||

| 4th hour | 37.8 ± 7.82 | 37.29 ± 5.19 | 0.736 | ||||||

| 8th hour | 37.85 ± 7.75 | 37.11 ± 5.91 | 0.636 | ||||||

| 12th hour | 35.93 ± 7.09 | 38.47 ± 6.12 | 0.094 | ||||||

| 24th hour | 37.05 ± 7.07 | 38.76 ± 6.38 | 0.266 | ||||||

| HCO3 | |||||||||

| 0th hour | 22.7 ± 3.43 | 22.63 ± 3.39 | 0.932 | ||||||

| 1st hour | 22.81 ± 2.84 | 22.47 ± 4.77 | 0.709 | ||||||

| 2nd hour | 22.49 ± 3.15 | 22.58 ± 3.75 | 0.910 | ||||||

| 3rd hour | 23.33 ± 3.28 | 22.71 ± 4.91 | 0.516 | ||||||

| 4th hour | 22.88 ± 4.87 | 23.11 ± 3.15 | 0.806 | ||||||

| 8th hour | 24.85 ± 3.73 | 23.42 ± 2.97 | 0.066 | ||||||

| 12th hour | 24.18 ± 2.75 | 24.87 ± 3.46 | 0.329 | ||||||

| 24th hour | 25.08 ± 3.27 | 26.16 ± 4.24 | 0.209 | ||||||

Abbreviation: PSB, parasternal block.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

4.6.3. Partial Arterial Oxygen Pressure (PaO2)

At the 8th hour, PaO2 levels in the PSB group were significantly higher than in the saline group (P = 0.032). No significant differences were found between the groups at other time points (Table 4).

4.6.4. Partial Arterial Carbon Dioxide Pressure (PaCO2) and Bicarbonate Levels

No significant differences were observed between the groups at any time point (Table 4).

4.7. Triflo Exercise Results

No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in Triflo exercise performance at the 1st, 4th, or 12th postoperative hours (Table 5).

4.8. Patient Satisfaction (Short Form-36 Assessment)

In the SF-36 survey administered on postoperative day 30, no significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of mental health (P = 0.522), physical functioning (P = 0.340), physical role (P = 0.317), social functioning (P = 0.835), pain (P = 0.821), general health perception (P = 0.712), emotional role (P = 0.762), or vitality (P = 0.496, Table 6).

| Parameters | Saline Group (N = 39) | PSB Group (N = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 60.00 ± 3.44 | 59.62 ± 3.51 | 0.340 |

| Physical role | 0.64 ± 4.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.317 |

| Emotional (social) role | 32.15 ± 5.28 | 32.50 ± 5.34 | 0.762 |

| Vitality | 42.95 ± 5.47 | 42.05 ± 6.95 | 0.496 |

| Mental health | 47.59 ± 7.04 | 48.82 ± 6.88 | 0.522 |

| Social function | 77.08 ± 13.46 | 77.72 ± 13.37 | 0.835 |

| Pain | 60.05 ± 12.06 | 60.64 ± 11.86 | 0.821 |

| General health perception | 37.69 ± 8.34 | 38.21 ± 7.65 | 0.712 |

Abbreviation: PSB, parasternal block.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of postoperative PSB application on extubation times, opioid consumption, and pain scores in patients undergoing CABG surgery with median sternotomy. The results demonstrated that PSB significantly shortened extubation times (P < 0.001) and reduced behavioral pain and numeric rating scores in the postoperative 24-hour period compared to the saline group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.024, respectively). It also delayed the first tramadol administration in the ICU and reduced the total tramadol requirement (P < 0.001). In the literature, studies conducted within the framework of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols following median sternotomy have reported that the PSB group exhibits lower pain scores than traditional pain management groups (13). With the adoption of ERAS programs in cardiac surgeries in recent years, the development of analgesic strategies that reduce opioid consumption has become increasingly important (14). Similarly, in our study, both the behavioral pain scores assessed while intubated and the numeric rating scores evaluated after extubation were found to be significantly lower in the PSB group than in the saline group.

Postoperative analgesia is critically important for improving patient comfort, accelerating the recovery process, and preventing pain-related sympathetic responses. Schwann and Chaney's study demonstrated that continuous intravenous opioid infusion reduces myocardial oxygen demand by lowering heart rate and blood pressure (15). Achieving stable hemodynamics and adequate pain control during this period is critically important. However, due to the side effects associated with opioid use, there has been a growing shift toward multimodal analgesia techniques. Various studies have highlighted the effectiveness of local anesthesia and analgesia techniques in pain control, preserving respiratory function, and shortening extubation times (16). A meta-analysis on PSB application showed a significant reduction in postoperative opioid consumption and demonstrated the effectiveness of this method in pain management (13). Consistent with these findings, our study revealed that the saline group, which required additional tramadol alongside paracetamol, had a significantly earlier and higher need for tramadol than the PSB group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) (17). In terms of extubation times, the durations were found to be significantly shorter in the PSB group. This finding indicates that the application of a PSB improves postoperative pain control, leading to faster extubation.

Regarding hemodynamic parameters, previous studies have reported that PSB has positive effects on heart rate and systolic blood pressure (18). In our study, no significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of postoperative hemodynamic parameters. While this may partly be related to the limited sample size and the study protocols, a more plausible explanation is that the standard intraoperative opioid regimen (fentanyl infusion) and postoperative analgesia (paracetamol) provided adequate baseline hemodynamic control for both groups, thereby masking any additional modest stabilizing effect of the PSB.

Our study has some limitations:

1. It was difficult to determine differences between the groups in terms of pain reduction, early tracheal extubation, and recovery time, as the ICU team’s discharge protocols were not modified.

2. The use of different brands of Triflo devices in respiratory exercises may have influenced the results.

3. The postoperative analgesia protocols were based on the hospital's routine practices, which may have masked differences between the groups.

4. The criteria for tracheal extubation were not objectively standardized.

5. Pain scores were analyzed at multiple time points without adjustment for type I error inflation (e.g., Bonferroni correction). Therefore, the interpretation of our findings should take into account the increased risk of overstating statistical significance.

Despite these limitations, our study strongly supports the effectiveness of PSB in pain management following sternotomy. The PSB appears to have significant potential, particularly in reducing opioid consumption and lowering pain scores (19).

5.1. Conclusions

Our study found that PSB applied during CABG surgery was effective in reducing opioid consumption and significantly shortened extubation times in the block group. The PSB is considered an effective method for reducing postoperative pain in patients undergoing open-heart surgery. Comprehensive, large-scale, multicenter studies with diverse protocols are needed to better understand the effectiveness, feasibility, indications, and contraindications of this block method in open-heart surgeries.