1. Background

The axillary approach to the brachial plexus block is commonly employed for upper limb surgeries due to its effectiveness and lower risk of complications compared to more proximal methods, such as the interscalene or supraclavicular approaches (1, 2). This technique provides effective analgesia and anesthesia with fewer systemic side effects compared to general anesthesia and has a favorable safety profile, particularly in patients with respiratory comorbidities. It offers reliable surgical anesthesia and postoperative analgesia, making it a preferred choice for hand and forearm surgeries.

Ropivacaine, an amide local anesthetic, is widely used in peripheral nerve blocks because of its reduced cardiotoxicity and central nervous system effects compared to bupivacaine (3). However, despite its advantages, ropivacaine alone may not provide adequate postoperative analgesia for all patients, especially during longer surgical procedures. To extend the duration and enhance the quality of peripheral blocks, various adjuvants — such as dexamethasone, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium — have been explored to enhance the duration and quality of analgesia achieved with local anesthetics (4, 5). Recent studies continue to investigate optimal adjuvant combinations with ropivacaine in various regional anesthesia techniques (6). However, the efficacy and safety of neostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, as an adjuvant in peripheral nerve blocks remain contentious.

Neostigmine has garnered interest as an adjuvant due to its mechanism of increasing acetylcholine concentration at the neuromuscular junction, potentially enhancing both sensory and motor blockades (7). It amplifies cholinergic transmission — specifically through the accumulation of acetylcholine at synaptic clefts, which may modulate nociceptive and motor neuron activity (8). By inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine, neostigmine theoretically prolongs the effects of local anesthetics on nerve fibers, making it a promising option for regional anesthesia.

However, clinical outcomes with neostigmine as an adjuvant in peripheral nerve blocks have been inconsistent. Although some studies have shown promising results with neostigmine in spinal and epidural anesthesia, its role in peripheral nerve blocks is less established, with mixed outcomes reported (9, 10). Some studies suggest that neostigmine may prolong sensory and motor blockade, while others report no significant benefit and increased side effects, such as nausea and vomiting (11, 12).

Furthermore, the potential side effects of neostigmine — including cholinergic symptoms such as bradycardia, increased salivation, and gastrointestinal disturbances — raise concerns about its use as a routine adjuvant in peripheral nerve blocks. These adverse effects are thought to be related to systemic absorption and activation of muscarinic receptors, which can complicate perioperative management. Consequently, although neostigmine shows promise as an adjuvant in some contexts, its role in peripheral nerve blocks, such as the axillary brachial plexus block, remains uncertain. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of neostigmine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in axillary brachial plexus blocks for patients undergoing hand and forearm surgery.

2. Objectives

The objective was to determine whether the addition of neostigmine could improve the onset and intensity of sensory and motor block, hemodynamic stability, and the incidence of adverse events compared to ropivacaine alone.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This double-blind, randomized controlled trial included 40 adult patients [American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-II], aged 18 - 70 years, undergoing elective hand and forearm surgery. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences and was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

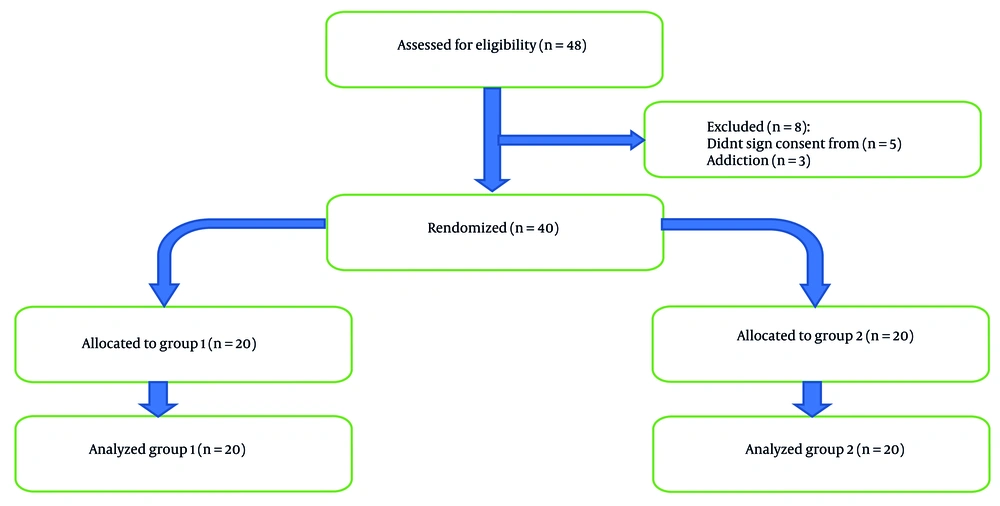

Eligible participants included adult patients aged 18 to 70 years with ASA physical status I or II, scheduled for elective hand or forearm surgery under axillary brachial plexus block. Exclusion criteria were allergies to local anesthetics or neostigmine, pregnancy, breastfeeding, coagulopathy, severe renal or hepatic impairment, uncontrolled systemic diseases, preexisting neuropathy (e.g., diabetic, traumatic, or compressive neuropathies), and history of substance abuse or seizures (Figure 1).

3.3. Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomized into two groups using a computer-generated randomization table with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The allocation was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE). An independent nurse anesthetist, who was not involved in the study, implemented the randomization by opening the next envelope in sequence and preparing the study solution accordingly. Group 1 (neostigmine group) received 30 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine combined with 500 µg of neostigmine (total volume 31 mL), while group 2 (placebo group) received 30 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine with 1 mL of normal saline as a placebo. The study solutions were prepared by an independent nurse anesthetist who was not involved in the study and was blinded to the group allocation and research hypothesis to ensure that both participants and outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation.

3.4. Procedure

Standard monitoring, including electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry, was applied to all patients. Sedation was achieved with intravenous midazolam (0.03 mg/kg) and fentanyl (1 µg/kg) prior to block placement. The axillary brachial plexus block was performed using a high-frequency linear ultrasound probe (e.g., SonoSite X-Porte) and a nerve stimulator (initial current 0.5 mA, frequency 2 Hz, pulse width 0.1 ms) to identify the target nerves, and the study solution was injected around the brachial plexus in the axilla. The sensory and motor blockades were evaluated every 3 minutes after injection until a complete block was achieved. Once complete, anesthesia was confirmed, and surgery was allowed to commence.

If a patient reported pain at the surgical site or tourniquet site intraoperatively, the time of pain onset was noted. Initially, an intravenous fentanyl dose of 1 µg/kg was administered for analgesia; if pain persisted despite fentanyl, the patient was converted to general anesthesia (such patients were not excluded from the final analysis). After surgery, patients were transferred to the recovery room. The time to first report of pain [using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)] and the time to return of limb movement were monitored every 5 minutes. If the NRS pain score reached 3 or higher, a rescue analgesic (pethidine 1 mg/kg IV) was administered. Throughout the intraoperative and postoperative periods (from block placement to the end of recovery), blood pressure, heart rate, total opioid consumption, and any complications (hypotension, bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, or motor disturbances) were recorded. Bradycardia (heart rate < 50 beats/min) was treated with atropine 0.75 mg IV, and hypotension was managed with an IV bolus of ephedrine 5 mg.

3.5. Outcome Measures

3.5.1. Primary Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the onset times of sensory and motor blockade, defined as the time from the end of the injection to the complete loss of sensation (pinprick method) and motor function (thumb adduction/abduction), respectively.

3.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included time to first request for opioid analgesia after recovery of sensory block, total opioid consumption within 24 hours, hemodynamic parameters (heart rate and blood pressure at defined intervals), and the incidence of adverse events such as nausea, vomiting, and hypotension.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

Based on data from a previous study (4), a sample size of 18 patients per group was calculated using the following equation:

Where sd1 and sd2 were 3 and 4.6, respectively. Also, d was set at 3.6. The Z1-α/2 and Z1-β were 1.96 and 0.84. To account for potential dropouts (10%), we enrolled 20 patients in each group (total N = 40).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range; IQR) based on normality of distribution. Continuous variables were compared between groups using the independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups were comparable. There were no significant differences between the neostigmine and placebo groups in age, gender distribution, Body Mass Index (BMI), or baseline hemodynamic parameters (all P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Variables | Neostigmine Group (n = 20) | Placebo Group (n = 20) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 17 (85) | 18 (90) | |

| Female | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | |

| Age (y) | 29.25 ± 9.41 | 30.35 ± 11.10 | 0.74 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.15 ± 3.46 | 26.25 ± 5.08 | 0.43 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

4.2. Primary Outcomes

The mean onset time of sensory blockade was 8.20 ± 2.72 minutes in the neostigmine group versus 8.85 ± 3.37 minutes in the placebo group (P > 0.05). The mean difference in the onset of sensory block was -0.65 min [95% confidence interval (CI): -2.45 to 1.15, P = 0.51]. The onset time of motor blockade was 12.25 ± 6.60 minutes in the neostigmine group compared to 17.5 ± 3.53 minutes in the placebo group, a difference that was not statistically significant. The mean difference in the onset of motor block was -5.25 min (95% CI: -11.82 to 1.32; P = 0.37). The durations of the sensory (P = 0.71) and motor blocks (P = 0.62) were also similar between the neostigmine and placebo groups, with no statistically significant differences observed (P > 0.05 for both; Table 2).

| Variables | Neostigmine Group (n = 20) | Placebo Group (n = 20) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset time of sensory block (min) | 8.20 ± 2.72 | 8.85 ± 3.37 | -0.65 (-2.45 to 1.15) | 0.51 |

| Onset time of motor block (min) | 12.25 ± 6.60 | 17.50 ± 3.53 | -5.25 (-11.82 to 1.32) | 0.37 |

| Duration of sensory block (min) | 186.87 ± 9.73 | 184.00 ± 11.25 | 2.87 (-3.86 to 9.60) | 0.71 |

| Duration of motor block (min) | 172.75 ± 8.43 | 175.25 ± 9.37 | -2.50 (-8.20 to 3.20) | 0.62 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.3. Pain Intensity (Block Intensity)

According to the NRS evaluations, there was no significant difference in pain intensity between the groups during the procedure or in the recovery room, and none of the patients in either group reported severe pain during the procedure (P = 0.08). Notably, no patient required conversion to general anesthesia due to inadequate block.

4.4. Hemodynamic Stability

Both groups maintained stable hemodynamic profiles intraoperatively and postoperatively. There were no significant differences in heart rate during operation and recovery (P = 0.99 and 0.07), or systolic (P = 0.96 and 0.82) and diastolic blood pressures (P = 0.43 and 0.89) between the neostigmine and placebo groups at any recorded time point. However, a non-significant trend toward a lower median heart rate was observed in the neostigmine group during the recovery period [64 (IQR: 18) vs. 73.5 (IQR: 15) beats per minute, P = 0.07; Table 3].

| Variables | Neostigmine Group | Placebo Group | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP during operation (mmHg) | 124.58 ± 13.31 | 124.35 ± 11.90 | 0.23 (-7.85 to 8.31) | 0.96 |

| SBP during recovery (mmHg) | 116.26 ± 16.14 | 117.35 ± 12.74 | -1.09 (-10.40 to 8.22) | 0.82 |

| DBP during operation (mmHg) | 79.79 ± 8.92 | 77.50 ± 8.91 | 2.29 (-3.42 to 8.00) | 0.43 |

| DBP during recovery (mmHg) | 72.05 ± 11.93 | 72.50 ± 8.74 | -0.45 (-7.14 to 6.24) | 0.89 |

| HR during operation (bpm), median (IQR) | 80 (10) | 80 (14) | NA b | 0.99 |

| HR during recovery (bpm), median (IQR) | 64 (18) | 73.5 (15) | NA b | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR).

b Not applicable [non-parametric data, presented as median (IQR)].

4.5. Adverse Events

No significant differences were noted in the incidence of adverse events between groups. In the neostigmine group, three patients (15%) experienced mild nausea, whereas no patients in the placebo group reported nausea; this difference was not statistically significant. No cases of vomiting, clinically significant bradycardia, or hypotension were observed in either group. Overall, 85% of patients in the neostigmine group and 100% in the placebo group had no complications recorded (P = 0.23 for incidence of any complication). There were also no signs of motor weakness beyond the expected duration of the block in any patient (Table 4).

| Variables | Neostigmine Group (n = 20) | Placebo Group (n = 20) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to first opioid request after sensory block recovery (min) | 17.00 ± 7.21 | 16.50 ± 4.40 | 0.50 (-3.32 to 4.32) | 0.88 |

| Patients with any nausea | 3 (15) | 0 (0) | NA b | 0.23 |

| Patients requiring a second opioid dose | 6 (30) | 8 (40) | RR: 0.75 (0.31 to 1.81) | 0.51 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Not applicable [categorical data, presented as No. (%)]

5. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that adding neostigmine to ropivacaine for an axillary brachial plexus block did not significantly alter the onset or duration of sensory and motor blockade compared to ropivacaine alone. However, it is important to interpret these null findings in the context of the study's statistical power. The sample size was calculated to detect a large difference in block duration and may have been underpowered to detect smaller, yet clinically relevant, effects. For instance, the observed difference in motor block onset time — a mean reduction of over five minutes in the neostigmine group — is substantial from a clinical perspective. This numerical trend is biologically plausible, given neostigmine's known mechanism of enhancing cholinergic transmission at the neuromuscular junction, which theoretically could accelerate motor blockade. A larger trial would be required to determine if this observed difference represents a true effect.

Moreover, the clinical significance of the observed differences must be considered. For example, the 5.25-minute difference in motor block onset, while notable, may not translate to a meaningful clinical advantage in the operating room. Similarly, the small differences in block duration (approximately three minutes for sensory and 2.5 minutes for motor block) are unlikely to impact postoperative pain management or patient satisfaction. These findings further support the conclusion that neostigmine does not provide clinically important enhancements to ropivacaine brachial plexus blocks.

These results align with those of Roelants et al., who found that neostigmine did not alter the need for patient-controlled epidural local anesthesia during labor (13). Similarly, Bouaziz et al. reported no enhancement in sensory or motor blockade when 500 µg of neostigmine was added to mepivacaine in an axillary plexus block, instead noting a higher incidence of side effects with neostigmine (10).

In contrast, some studies have suggested that neostigmine may offer benefits in specific settings. For example, Alagol et al. concluded that the most effective drugs administered intra-articularly were neostigmine and clonidine among the five drugs they studied (14). Furthermore, any definitive conclusion regarding the inefficacy of neostigmine must be tempered by the fact that it is based on a single dose of 500 µg. The optimal dose for perineural administration, or whether a meaningful dose-response relationship exists for peripheral nerve blocks, remains unknown and warrants systematic investigation. Different dosing regimens or concentrations could potentially yield different results.

The lack of significant benefit observed with neostigmine in our peripheral nerve block study could be related to pharmacokinetic factors. Unlike central neuraxial blocks (spinal or epidural), where neostigmine can directly affect receptors in the spinal cord, perineural administration of neostigmine in a plexus block may result in insufficient local concentration at the nerve fibers to meaningfully prolong blockade (10). In essence, neostigmine’s mechanism of action — acetylcholinesterase inhibition and increased acetylcholine levels — may not be as effective in the peripheral nerve environment. Previous research has suggested that neostigmine’s analgesic efficacy is more pronounced in central blocks (epidural or intrathecal) than in peripheral nerve blocks (9).

Another consideration is that ropivacaine's intrinsic properties might overshadow any potential additive effect of neostigmine. Ropivacaine is a long-acting local anesthetic with a propensity for producing a differential sensory block. Its long duration of action may leave little room for further prolongation by adjuvants, which could explain why we observed no differences in block duration or in postoperative opioid requirements between the neostigmine and placebo groups. Moreover, our finding of similar analgesic consumption in both groups is consistent with reports that the addition does not reduce postoperative pain scores or analgesic needs in peripheral blocks (10).

Importantly, although neostigmine did not improve block characteristics, we also did not observe significant hemodynamic disturbances attributable to its use. This is in line with the findings of Demirel et al. (8), which reported no severe hemodynamic instability when neostigmine was used in a regional anesthetic context. In our study, heart rate and blood pressure remained stable, and the incidence of bradycardia or hypotension was low and similar between groups. Although a non-significant trend toward a lower heart rate was noted in the recovery room for the neostigmine group, no patient required pharmacological intervention for bradycardia. This physiological finding is not trivial; it aligns directly with the known cholinergic effects of systemically absorbed neostigmine and provides evidence of a measurable, albeit subclinical, systemic biological activity. This trend warrants consideration in future, larger studies.

Furthermore, we noted a higher incidence of mild nausea in the neostigmine group (15% vs. 0%), which aligns with the established muscarinic side effect profile of the drug and findings from other studies (7, 8). Neostigmine’s ability to cause nausea and other cholinergic effects is a known limitation and suggests caution in its use as a peripheral nerve block adjuvant, since these side effects can diminish patient comfort.

The observed duration of both sensory and motor blockade (approximately 185 minutes) in our study is shorter than some previously reported durations for ropivacaine 0.5% in brachial plexus blocks. This may be related to our specific definition of block cessation, which was the first report of pain in the surgical distribution for sensory block and the return of thumb movement for motor block. Other studies may use different endpoints, such as time to first analgesic request, which can be later than the initial perception of pain. Furthermore, the surgical stimulus and individual patient variations in drug metabolism can also influence the perceived duration of the block.

Other adjuvants have shown more consistent success in prolonging block duration and improving analgesia. For instance, dexamethasone and clonidine have been repeatedly shown to significantly extend the duration of nerve blocks without major side effects (15). Lee et al. found that adding dexamethasone to ropivacaine in an axillary block prolonged analgesia significantly, and did so without increasing adverse effects (4). Likewise, a network meta-analysis by Hussain et al. (3) concluded that both dexamethasone and clonidine are effective in prolonging peripheral nerve blocks, with an acceptable safety profile. This is further supported by recent research comparing adjuvants for ropivacaine in other regional blocks, reinforcing the superior efficacy profile of dexamethasone compared to other agents (16). In comparison, our results (and much of the literature) suggest that neostigmine’s benefits, if any, do not clearly outweigh its side effects for peripheral nerve block use.

Furthermore, a systematic review by Guerra-Londono et al. (17) emphasizes that the effectiveness of various adjuvants can depend on the type of surgery and patient population. This underscores the importance of tailoring adjuvant choice to the clinical scenario. While neostigmine might still have a niche role (for example, in central neuraxial blocks or intra-articular injections as noted above), its routine use in brachial plexus blocks is not supported by our findings. Lastly, Joshi-Khadke et al., in a meta-analysis of intrathecal neostigmine, noted that any sensory block enhancement by neostigmine was often accompanied by increased risk of side effects (9). Translating that to the peripheral setting, it appears that neostigmine offers limited upside with a potential downside of nausea or other cholinergic effects.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size (20 patients per group) was calculated to detect a large difference in block duration; it may have been underpowered to detect smaller but clinically relevant differences in some outcomes. Second, we used a single dose of neostigmine (500 µg) based on prior studies; different dosing or concentrations were not explored and could potentially yield different results. Third, all patients received mild sedation and supplemental analgesia (fentanyl) during block placement, which might have minimized detectable differences in intraoperative comfort or block efficacy between groups. However, this approach reflects common clinical practice and was applied equally to both groups. Fourth, our study focused on a single nerve block technique (axillary approach) and one local anesthetic (ropivacaine); the findings may not be generalizable to other block locations or shorter-acting local anesthetics. Indeed, neostigmine might have a more noticeable effect when used with shorter-acting drugs (e.g., lidocaine) or in blocks of shorter expected duration. Finally, we did not measure plasma levels of neostigmine or investigate its pharmacodynamics in the peripheral nerve tissue; thus, we can only speculate on the reasons for its lack of efficacy in this context.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the addition of 500 µg of neostigmine to 0.5% ropivacaine in an axillary brachial plexus block did not significantly enhance the onset, intensity, or duration of sensory and motor blockade in patients undergoing hand and forearm surgery. The neostigmine–ropivacaine combination was found to be as safe as ropivacaine alone in terms of hemodynamic stability, with no clinical events requiring intervention, but the use of neostigmine was associated with a trend toward more frequent mild nausea without any clear analgesic benefit. Therefore, neostigmine may not be the ideal adjuvant for axillary brachial plexus blocks in hand and forearm surgeries. Future research should focus on exploring other adjuvants or combinations, as well as different doses or routes for neostigmine, to improve peripheral nerve block outcomes. Ultimately, identifying the ideal adjuncts for prolonging nerve block analgesia will help maximize patient comfort and minimize the need for systemic analgesics in the perioperative period.