1. Background

The prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) has steadily increased since 1990. While cardiovascular disease-related mortality has decreased by 24.7%, CAD continues to impose a major health burden, being responsible for almost one-third of all deaths in individuals over the age of 35. In this context, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) persists as a fundamental treatment modality for advanced CAD (1). Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) represents a common and serious adverse event following cardiovascular surgery, contributing to higher morbidity in both the early and late phases. Its incidence is reported to be approximately 30% in individuals undergoing CABG, 40% in those undergoing valve surgery, and up to 50% in those undergoing combined CABG with valve replacement or repair, with peak onset occurring between the second and third postoperative days (2). The POAF is linked to a wide spectrum of complications, ranging from hemodynamic instability and thromboembolic events to prolonged hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) readmissions, organ failure, greater healthcare burden, and increased risk of death. Accordingly, substantial clinical attention is directed toward preventive measures for atrial fibrillation (AF) in individuals identified as high risk (3, 4).

The AF arises from a complex interplay of pathophysiological processes influenced by diverse risk factors. Multiple diagnostic methods are available that aid in the prediction of POAF (5). Several investigations have focused on identifying demographic risk factors as well as predictors contributing to the development of postoperative AF (6, 7). Multiple perioperative variables influence the incidence of postoperative AF after conventional CABG, notably older age, hypertension (HTN), discontinuation of β-blockers, right coronary artery stenosis, respiratory complications, and hemorrhagic events (8, 9). The incidence of postoperative AF has also been linked to inadequate atrial cardioplegic protection during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and to myocardial ischemia. However, reliance on clinical variables alone has proven insufficient for accurately identifying individuals at risk of POAF. Consequently, clinical data by itself cannot be solely used to guide prophylactic strategies (10).

In addition to transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)-based evaluation, other intraoperative approaches have been investigated for optimizing cardiac surgical outcomes. For example, the Saline Injection Leak Test Without Transesophageal Echocardiography has been proposed as a reliable method during valve repair procedures, emphasizing the importance of intraoperative assessment modalities beyond TEE (11). Furthermore, sedative agents such as dexmedetomidine have been shown to influence postoperative neurological and hemodynamic outcomes in cardiac surgery (12), highlighting how intraoperative pharmacologic strategies may also impact postoperative arrhythmic risk.

2. Objectives

This investigation aims to evaluate the role of TEE in predicting POAF through assessment of left atrial (LA) measurements as potential predictors.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Population

This prospective cohort investigation was conducted in the Departments of Anesthesia and Cardiothoracic Surgery, Mansoura University hospitals, Egypt, over a one-year period from January 2022 to January 2023. A total of 70 adult cases undergoing on-pump CABG were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included concomitant cardiac procedures, prior atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, use of antiarrhythmic medications other than β-blockers and digoxin, and contraindications to TEE.

3.2. Assessments

All cases were subjected to a comprehensive preoperative assessment, including detailed medical history, physical examination, and routine laboratory and radiological investigations. Intramuscular morphine (0.1 mg/kg) was administered one hour before surgery as premedication. Hemodynamic monitoring included measurement of heart rate using a five-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and arterial pressures (systolic, diastolic, and mean) via a radial arterial catheter placed under local anesthesia with midazolam sedation (0.07 mg/kg). Central venous pressure, body temperature, and urine output were continuously monitored. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 0.5 mg/kg, fentanyl 5 mg/kg, and rocuronium 0.6 mg/kg. Following tracheal intubation, cases were ventilated with an oxygen-air mixture (60:40). Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved with sevoflurane (0.5 - 2%) in addition to supplemental doses of fentanyl and rocuronium as required. All anesthetic inductions and maintenance regimens adhered to a uniform institutional protocol; no deviations from the described drug combinations or dosages occurred apart from minor hemodynamic titration.

3.3. Procedure

Following initiation of standard monitoring and induction of anesthesia, a 3.5 - 7 MHz phased-array TEE probe, either multiplane or biplane (Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA), was introduced. Cardiac imaging was performed in multiple planes: Zero - one hundred twenty degree for multiplane probes, and transverse and longitudinal orientations for biplane probes. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure or pulmonary artery diastolic pressure was documented during the TEE examination. Assessments were carried out at two time points, pre-cardiopulmonary bypass (pre-CPB, before sternotomy) and post-cardiopulmonary bypass (post-CPB, after sternal closure), under stable hemodynamic conditions. Pulmonary venous and transmitral flow velocities were measured during brief apnea and averaged across several cardiac cycles. All studies were digitally archived and reviewed independently by two blinded investigators; in cases with discrepancies exceeding 5%, a third investigator repeated the measurements, and the mean of the three results was used. Standard imaging views included the midesophageal four-chamber, midesophageal two-chamber, midesophageal bicaval, and transgastric mid-short axis. Doppler data were synchronized with ECG. Parameters evaluated included left and right atrial dimensions, left atrial appendage area (LAAA), outflow velocity from the LA appendage, pulmonary venous inflow, mitral and tricuspid inflow velocities, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left atrial kinetic energy (LAKE), and left atrial ejection force (LAEF).

Following CABG, postoperative management adhered to standard sedation and analgesia protocols, which included fentanyl (0.7 - 10 µg/kg/h), propofol (0.3 - 3 mg/kg/h), and paracetamol up to 4 g per day. All cases underwent continuous five-lead ECG monitoring for 72 hours in the ICU, along with daily 12-lead ECG recordings to document episodes of AF.

3.4. Data Collection

The primary outcome was the evaluation of LA function, encompassing left and right atrial dimensions, LAAA, LAKE, LAEF, LA appendage outflow velocity, pulmonary venous inflow velocities, mitral and tricuspid inflow velocities, and LVEF. Secondary outcomes were categorized into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative domains. Preoperative variables consisted of demographic and clinical data [age, sex, smoking, HTN, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), prior myocardial infarction (MI), dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus (DM), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)], medication use, vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate), renal function (creatinine or need for hemodialysis), and echocardiographic results. Operative variables included cross-clamp time, CPB duration, nadir temperature, number of grafts, intraoperative complications (hemodynamic instability, arrhythmias, acute MI, intra-aortic balloon pump requirement, and bleeding), administration of inotropes (adrenaline, dopamine, noradrenaline, nitroglycerin, dobutamine, and sodium nitroprusside), transfusion requirements (platelets, packed red blood cells, and fresh frozen plasma), and TEE findings. Postoperative outcomes evaluated were duration of mechanical ventilation (MV), ICU and hospital length of stay, mortality, shock, stroke, infection, renal failure, and bleeding events. The third outcome was evaluation of morbidity and mortality associated with POAF. The AF was diagnosed by the attending cardiologist or intensivist based on continuous ECG monitoring in the ICU or standard ECG assessment in the ward. The diagnostic criteria included an irregularly irregular rhythm with absent P-waves on a 12-lead ECG. The AF occurred predominantly within the first 48 hours postoperatively, mostly during the ICU stay. Out of 18 total cases of postoperative AF, only 3 (16.7%) required urgent medical intervention. No patients developed permanent AF; all episodes were transient or paroxysmal.

3.5. Study Endpoint

The primary endpoint of this study was the occurrence of AF within the early postoperative phase, i.e., from the time of surgery to hospital discharge, limited to a maximum of 10 days.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

The required sample size was calculated using the IBM® SPSS® Sample Power® version 3.0.1 (IBM® Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The primary outcome measure was the incidence of AF in the patients undergoing coronary artery bypass with detailed TEE examinations. A previous study conducted by Shore-Lesserson et al. reported that the incidence of AF was 35.4% (13). Thus, it was estimated that a minimal sample size of 70 patients would be required to achieve a power of 80% to detect the expected difference in the incidence of AF of 15% at a significance level of 0.05.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 22). For categorical variables, results were presented as absolute frequencies and corresponding percentages. Quantitative data underwent assessment for distribution pattern with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables conforming to a normal distribution were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, whereas skewed variables were described as median values with ranges. The choice of statistical method was based on the type of data analyzed, with the chi-square test employed for categorical comparisons. Statistical significance was set at a threshold of P < 0.05.

4. Results

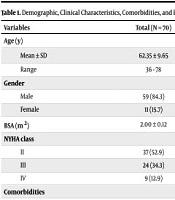

Table 1 demonstrates a substantial variation in age between the AF and No-AF groups (P = 0.031), with cases in the AF group being older. No marked variations were observed regarding gender, body surface area (BSA), or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (P = 0.169, 0.58, and 0.85, respectively). The HTN and previous MI were significantly more prevalent in the AF group relative to the No-AF group (P = 0.027 and ≤ 0.001, respectively). Differences in DM, COPD, smoking, PVD, and previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were not statistically significant (P = 0.503, 0.103, 0.128, 0.271, and 0.095, respectively).

| Variables | Total (N = 70) | AF Group (N = 18, 25.7%) | No-AF Group (N = 52, 74.3%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 62.35 ± 9.65 | 66.61 ± 6.14 | 61.07 ± 10.02 | 0.031 b |

| Range | 36 - 78 | 58 - 74 | 36 - 78 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 59 (84.3) | 17 (94.4) | 42 (80.8) | 0.169 |

| Female | 11 (15.7) | 1 (5.6) | 10 (19.2) | |

| BSA (m2) | 2.00 ± 0.12 | 1.99 ± 0.15 | 2.01 ± 0.11 | 0.580 |

| NYHA class | ||||

| II | 37 (52.9) | 9 (50) | 28 (53.8) | 0.853 |

| III | 24 (34.3) | 6 (33.3) | 18 (34.6) | |

| IV | 9 (12.9) | 3 (16.7) | 6 (11.5) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HTN | 43 (61.4) | 15 (83.3) | 28 (53.8) | 0.027 b |

| DM | 42 (60.0) | 12 (66.7) | 30 (57.7) | 0.503 |

| COPD | 11 (15.7) | 5 (27.8) | 6 (11.5) | 0.103 |

| Smoking | 32 (45.7) | 11 (61.1) | 21 (40.4) | 0.128 |

| PVD | 3 (4.3) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.271 |

| Previous MI | 28 (40.0) | 14 (77.8) | 14 (26.9) | ≤ 0.001 b |

| Previous PCI | 8 (11.4) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (7.7) | 0.095 |

| Preoperative medications | ||||

| β-blocker | 53 (75.7) | 14 (77.8) | 39 (75.0) | 0.813 |

| Digoxin | 4 (5.7) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (3.8) | 0.160 |

| ACEI | 19 (27.1) | 7 (38.9) | 12 (23.1) | 0.194 |

| Ca channel blocker | 15 (21.4) | 5 (27.8) | 10 (19.2) | 0.446 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BSA, body surface area; NYHA, New York Heart Association; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; BB, beta-blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; Ca, calcium.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

b Statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

Similarly, no substantial intergroup variations were noted regarding preoperative medications, including β-blockers, digoxin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers (P = 0.813, 0.160, 0.194, and 0.446, respectively).

Table 2 demonstrates marked variations between both groups in pre-CPB) ejection fraction (EF), pre-cardiopulmonary bypass end-systolic diameter (pre-CPB ESD), pre-CPB end-diastolic diameter (EDD), pre-CPB LA transverse diameter, pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (90° view, cm), pre-CPB LAAA, post-CPB left atrial appendage maximum velocity (LAA maxV), pre-CPB left upper pulmonary vein systolic-diastolic ratio (LUPVSDR), and post-CPB LUPVSDR (all P < 0.05). Highly substantial variations were also detected in LAKE (P ≤ 0.001) and LAEF (P ≤ 0.001). By comparison, no substantial variation was observed in pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (P = 0.233).

| Parameters | Total (N = 70) | AF group (N = 18) | No-AF Group (N = 52) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-CPB LA transverse diameter (cm) | 4.09 ± 0.21 | 4.21 ± 0.23 | 4.08 ± 0.19 | 0.007 b |

| Pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (cm) | 4.39 ± 0.33 | 4.47 ± 0.31 | 4.36 ± 0.33 | 0.233 |

| Pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (90° view, cm) | 4.53 ± 0.26 | 4.63 ± 0.25 | 4.49 ± 0.26 | 0.050 b |

| Pre-CPB LAA area (cm2) | 3.05 ± 0.52 | 3.66 ± 0.62 | 2.84 ± 0.26 | ≤0.001 b |

| LAA max V post-CPB (m/s) | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 0.39 ± 0.10 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | ≤ 0.001 b |

| Pre-CPB EF (%) | 56.18 ± 9.24 | 51.27 ± 10.13 | 57.88 ± 8.30 | 0.008 b |

| Pre-CPB ESD (cm) | 3.54 ± 0.69 | 4.08 ± 0.88 | 3.35 ± 0.49 | ≤ 0.001 b |

| Pre-CPB EDD (cm) | 5.07 ± 0.68 | 5.41 ± 0.88 | 4.96 ± 0.56 | 0.015 b |

| Pre-CPB LUPVSDR | 1.45 ± 0.33 | 1.25 ± 0.39 | 1.51 ± 0.28 | 0.003 b |

| Post-CPB LUPVSDR | 1.64 ± 0.36 | 1.10 ± 0.29 | 1.82 ± 0.12 | ≤ 0.001 b |

| LAKE (kdyne × cm) | 2.46 ± 0.91 | 1.27 ± 0.12 | 2.76 ± 0.73 | ≤ 0.001 b |

| LAEF (kdyne) | 2.03 ± 0.70 | 0.88 ± 0.26 | 2.14 ± 0.48 | ≤ 0.001 b |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; LA, left atrium; LAA, left atrial appendage; max V, maximum velocity; EF, ejection fraction; ESD, end-systolic diameter; EDD, end-diastolic diameter; LUPVSDR, left upper pulmonary vein systolic-diastolic ratio; LAKE, left atrial kinetic energy; LAEF, left atrial ejection force.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

b Statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

Table 3 demonstrates a substantial variation between both groups regarding intraoperative use of epinephrine inotrope (P = 0.011). No substantial variations were detected between both groups in other intraoperative variables, including number of grafts, temperature, CPB time, aortic cross-clamp time, post-weaning CPB left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, post-weaning CPB ventricular arrhythmia, and use of milrinone inotrope (P = 0.514, 0.487, 0.908, 0.090, 0.103, 0.566, and 1.00, respectively).

| Parameters | Total (N = 70) | AF Group (N = 18) | No-AF Group (N = 52) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of grafts | 2.87 ± 0.70 | 2.77 ± 0.73 | 2.90 ± 0.69 | 0.514 |

| Temperature (°C) | 28.13 ± 1.32 | 27.94 ± 1.14 | 28.19 ± 1.38 | 0.487 |

| CPB time (min) | 155.74 ± 45.54 | 154.66 ± 36.66 | 156.11 ± 48.55 | 0.908 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time (min) | 98.28 ± 28.19 | 108.00 ± 30.70 | 94.92 ± 26.76 | 0.090 |

| Post-weaning CPB LV dysfunction | 5 (7.1) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (3.8) | 0.103 |

| Post-weaning CPB ventricular arrhythmia | 4 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.7) | 0.566 |

| Use of epinephrine inotrope | 8 (11.4) | 5 (27.8) | 3 (5.8) | 0.011 b |

| Use of milrinone inotrope | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; LV, left ventricle.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

Table 4 demonstrates no marked variations between both groups regarding postoperative complications, including bleeding, pneumonia, renal impairment, stroke, and prolonged MV > 24 hours (P = 0.431, 0.797, 1.00, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively). However, both ICU stay and overall hospital stay were markedly longer in the AF group relative to the No-AF group (P = 0.002 and ≤ 0.001, respectively).

| Parameters | Total (N = 70) | AF Group (N = 18) | No-AF Group (N = 52) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | 12 (17.1) | 2 (11.1) | 10 (19.2) | 0.431 |

| Pneumonia | 9 (12.9) | 2 (11.1) | 7 (13.5) | 0.797 |

| Renal impairment | 5 (7.1) | 1 (5.6) | 4 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Stroke | 3 (4.3) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (3.8) | 1.000 |

| Prolonged MV > 24 h | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1.000 |

| ICU stay (d) | 3.38 ± 0.98 | 4.01 ± 1.08 | 3.17 ± 0.85 | 0.002 b |

| Hospital stay (d) | 6.04 ± 2.32 | 7.89 ± 2.13 | 5.40 ± 2.04 | ≤ 0.001 b |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ICU, intensive care unit; MV, mechanical ventilation.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

b Statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

Table 5 shows that HTN, previous MI, pre-CPB ESD, and pre-CPB LA transverse diameter are statistically significant positive predictors of postoperative AF (P = 0.029, 0.003, 0.001, and 0.011, respectively), while post-CPB LAA maxV and post-CPB LUPVSDR are statistically significant negative predictors of postoperative AF (P = 0.022 and 0.003, respectively).

| Independent Predictors | Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | |

| HTN | 0.035 | 4.3 (1.1 - 16.6) | 0.029 a | 5.32 (1.2 - 23.8) |

| Previous MI | 0.001 | 9.5 (2.7 - 33.8) | 0.003 a | 9.4 (2.2 - 40.1) |

| Pre-CPB EF | 0.013 | 0.9 (0.8 - 0.98) | 0.177 | 0.173 (0.9 - 1.5) |

| Pre-CPB ESD | ≤ 0.001 | 6.8 (1.7 - 13.18) | 0.001 a | 5.1 (1.9 - 13.2) |

| Pre-CPB EDD | 0.025 | 2.6 (1.13 - 6.3) | 0.082 | 1.015 (0.01 - 1.7) |

| Pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (90° view, cm) | 0.050 | 8.1 (0.9 - 68) | 0.915 | 1.75 (0.01 - 123) |

| Pre-CPB LAAA area | ≤ 0.001 | 87 (10 - 760) | 0.636 | 2.21 (0.08 - 58) |

| LAA max V post-CPB | 0.002 | 0.001 (0.01 - 0.004) | 0.022 a | 0.001 (0.01 - 0.004) |

| Pre-CPB LA transverse diameter | 0.010 | 34.3 (1.19 - 42) | 0.011 a | 30.43 (2.2 - 42) |

| Pre-CPB LUPVSDR | 0.006 | 0.06 (0.001 - 0.45) | 0.171 | 0.68 (0.17 - 2.2) |

| Post-CPB LUPVSDR | 0.002 | 0.001 (0.001 - 0.024) | 0.003 a | 0.001 (0.002 - 0.014) |

| Use of epinephrine inotrope | 0.021 | 6.2 (1.3 - 29) | 0.180 | 3.39 (0.6 - 20.3) |

| LAKE | 0.001 | 0.001 (0.0 - 0.032) | 0.033 a | 0.02 (0.001 - 0.72) |

| LAEF | 0.003 | 0.002 (0.001 - 0.065) | 0.034 a | 0.014 (0.0 - 0.73) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; EF, ejection fraction; ESD, end-systolic diameter; EDD, end-diastolic diameter; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; LA, left atrium; LAAA, left atrial appendage area; LAA max V, left atrial appendage maximum velocity; LUPVSDR, left upper pulmonary vein systolic-diastolic ratio; LAKE, left atrial kinetic energy; LAEF, left atrial ejection force.

a Statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

5. Discussion

The incidence of POAF after cardiac surgery varies widely, ranging from approximately 10% to 40%, depending on the surgical procedure and patient characteristics. This arrhythmia has notable clinical significance, as it predisposes individuals to hemodynamic instability and thromboembolic events such as stroke. Furthermore, POAF prolongs both ICU and hospital stays and represents an important factor contributing to increased healthcare expenditure (14). Previous research has investigated demographic and surgical variables in an effort to identify perioperative risk factors predictive of POAF. Recognizing high-risk individuals allows for targeted prophylactic strategies, which may reduce the morbidity linked to POAF and lower the overall costs of CABG surgery (15). Recognition of pre-existing clinical risk factors for POAF — including advanced age, HTN, congestive heart failure, and its higher frequency in valvular heart disease — reinforces the concept of an underlying arrhythmogenic substrate contributing to its development (16).

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is routinely employed in the preoperative assessment of cardiac function, and multiple anatomical and functional parameters derived from TTE have been shown to correlate with POAF. These observations highlight the value of TTE in detecting atrial pathophysiological alterations that may precede the clinical onset of AF (17).

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the role of TEE in predicting POAF. A total of 70 cases undergoing on-pump CABG were assessed during the early postoperative period, defined as the interval between surgery and hospital discharge, not exceeding 10 days. Based on rhythm outcome, cases were categorized into an AF group (n = 18; 25.7%) and a No-AF group (n = 52; 74.3%).

Results of the current study revealed that the AF group was significantly older than the No-AF group (P = 0.031). In contrast, gender, BSA, and NYHA class did not differ markedly between groups (P = 0.169, 0.58, and 0.85, respectively). Marked differences were observed in LAKE and LAEF, both of which were substantially lower in the AF group (P ≤ 0.001 for each). Analysis revealed a markedly higher frequency of HTN and previous MI among cases who developed AF relative to those who did not (P = 0.027 and ≤ 0.001, respectively). However, the incidence of DM, COPD, smoking, PVD, and previous PCI did not differ markedly between both groups (P = 0.503, 0.103, 0.128, 0.271, and 0.095, respectively). Similarly, no substantial variations were noted regarding preoperative therapy with β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, digoxin, or calcium channel blockers (P = 0.813, 0.160, 0.194, and 0.446, respectively).

Comparable to our results, Farag et al. (18) demonstrated that both age and HTN were significantly associated with POAF development. Their study showed that cases in the POAF group were significantly older (58.92 ± 8.24 years) compared with those without POAF (55.39 ± 7.05 years, P = 0.043). The HTN exhibited a stronger correlation (P = 0.0135), being present in 83% of POAF cases versus 55% of those without AF. Conversely, gender, DM, and smoking status showed no significant association with AF after CABG. Advancing age is associated with the loss of myocardial fibers, increased atrial fibrosis, and collagen deposition, particularly around the sinoatrial node, resulting in altered atrial electrophysiology. These age-related structural and functional changes predispose individuals to POAF, while acute surgical trauma and inflammation act as triggering factors (19).

The present findings align with those of Dave et al. (20), who reported no association between DM and POAF, although other studies have demonstrated a significant relationship (21). The HTN is a well-documented risk factor for AF in the general population (22) and following CABG procedures (23).

With respect to echocardiographic parameters, our study demonstrated significant intergroup differences in pre-CPB EF, pre-CPB ESD, pre-CPB EDD, pre-CPB LA transverse diameter, pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter at 90° (lg90), pre-CPB LAAA, post-CPB LAA maxV, pre-CPB LUPVSDR, and post-CPB LUPVSDR (all P < 0.05). In contrast, no substantial variation was observed for pre-CPB LA longitudinal diameter (P = 0.233). The present findings are in agreement with those of Camci et al. (24), who demonstrated that reduced LAKE and LAEF serve as strong predictive parameters for the development of AF (23).

A significant association was observed between intraoperative use of epinephrine inotrope and the occurrence of AF (P = 0.011). However, no marked variations were identified between AF and No-AF groups in relation to other intraoperative data, including number of grafts, operative temperature, CPB duration, aortic cross-clamp time, post-weaning CPB LV dysfunction, ventricular arrhythmias, and use of milrinone inotrope (P = 0.514, 0.487, 0.908, 0.090, 0.103, 0.566, and 1.00, respectively). Similarly, Hashemzadeh et al. (25) demonstrated that adrenaline use was linked to a higher incidence of POAF. Previous research has shown that inotropes potentiate sympathetic nervous system activity, and this enhanced adrenergic response is a recognized factor predisposing to POAF (26). Intraoperative monitoring choices and sedative regimens — such as the depth of TEE use or the administration of dexmedetomidine — may also modulate atrial electrophysiology and postoperative outcomes, a topic warranting further investigation in relation to POAF (11, 12).

According to the current results, no significant association was observed between AF occurrence and postoperative complications such as bleeding, pneumonia, renal impairment, stroke, or prolonged MV > 24 hours (P = 0.431, 0.797, 1.00, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively). However, the AF group was characterized by significantly longer ICU and mean hospital stays compared with the No-AF group (P = 0.002 and ≤ 0.001, respectively). Consistent with the present results, Shore-Lesserson et al. (13) reported that cases who developed POAF had a median hospital stay of 10 days (range 3 - 22), compared with 8 days (range 5 - 20) in those without POAF.

Specifically, the present study demonstrated that HTN, previous MI, pre-CPB ESD, and pre-CPB LA transverse diameter were significant positive predictors of POAF (AF, P = 0.029, 0.003, 0.001, and 0.011, respectively). In contrast, post-CPB LAA maxV and post-CPB LUPVSDR were significant negative predictors (P = 0.022 and 0.003, respectively). These findings are consistent with the literature, where increased LA volume or diameter has been established as an independent predictor of POAF. Supporting this, previous studies have shown that individuals developing POAF after CABG exhibit greater atrial fibrosis and elevated Left Atrial Volume Index (LAVI) (27, 28). Although LAVI was not directly measured in our intraoperative TEE protocol, these findings support our observed LA dimension–related risk, as larger postoperative LAVI has emerged as an independent predictor for AF occurrence (29).

Conversely, the study by Shore-Lesserson et al. (13) demonstrated that age (P = 0.002), pre-CPB LAAA (P = 0.04), and post-CPB LUPVSDR (P = 0.03) were each independently associated with a higher risk of POAF when analyzed separately. The greatest incidence of AF was observed in individuals with the combined presence of advanced age, enlarged pre-CPB LAAA, and reduced post-CPB LUPVSDR. Farag et al. (18) demonstrated that dilated LA, septal e’ velocity, septal wall thickness, lateral E/e’ velocity, LAVI, HTN, left ventricular mass (LVM), and impaired LV function were the most significant independent predictors of AF development following CABG.

5.1. Conclusions

The incidence of POAF in this study was 25.7%. Echocardiography proved valuable in identifying key predictors, with dilated left atrium, increased LAVI, reduced LAKE, and reduced LAEF serving as significant determinants of AF after CABG.

5.2. Limitations and Generalizability

This study is subject to several limitations. First, being a single-center investigation, the findings should be validated in larger, multi-center cohorts. Second, the relatively small sample size and absence of long-term follow-up (≤ 10 days) restrict the generalizability of the results, emphasizing the importance of future prospective studies with larger populations and extended follow-up periods. Moreover, biomarkers related to atrial fibrosis, inflammation, and volume load were not examined, which might have offered additional insights into the mechanisms underlying POAF. Finally, the application of advanced echocardiographic techniques and artificial intelligence–based software for LA strain analysis may enhance predictive accuracy and warrants further exploration in future research. Electrolyte and metabolic indices, which may influence atrial excitability, were not systematically measured in all cases and therefore could not be analyzed; inclusion of these parameters in future studies is recommended.