1. Background

Hip fractures are among the most prevalent orthopedic problems in the elderly population, often associated with significant morbidity and mortality (1). Consequently, early surgical reduction and fixation are recommended for most patients with hip fractures (2). However, surgical intervention produces considerable pain, potentially impeding functional recovery, early rehabilitation, and patient satisfaction if not adequately managed (3). Comprehensive perioperative pain management strategies integrate systemic analgesics, neuraxial blocks, and peripheral nerve blocks. To reduce opioid consumption and improve post-operative pain control, several peripheral nerve blocks have been introduced, including fascia iliaca block, femoral nerve (FN) block, and various interfascial plane blocks, such as the quadratus lumborum block (4).

The lumbar plexus block (psoas compartment block) requires advanced skills and is time-consuming. The lumbar paravertebral region is non-compressible and vascular, conferring an increased risk of bleeding complications, especially in patients receiving anticoagulants. Furthermore, there are notable risks of inadvertent neuraxial block or intravascular injection, which may result in local anesthetic systemic toxicity (5). Notably, the quadratus lumborum block does not block certain nerve branches essential for hip joint innervation in hip fracture analgesia (6). Research indicates that both conventional and high-volume suprainguinal fascia iliaca blocks can significantly weaken muscle strength (7). The FN, obturator nerve (ON), and accessory obturator nerve (AON) provide innervation to the anterior hip capsule (8). As the anterior capsule is the most richly innervated part of the joint, it should be the primary target for hip analgesia, as indicated by previous studies (9).

The FN block typically does not block the articular branches of the AON or ON, and blocks of the FN can reduce quadriceps muscle strength (10). Giron-Arango et al. demonstrated the effective use of the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block for post-operative pain management in hip surgeries. The PENG block technique involves injecting local anesthetic between the psoas muscle and the superior pubic ramus within the musculofascial plane, targeting the articular branches of the FN, ON, and AON, which innervate the anterior hip capsule. The PENG block, using 20 mL of local anesthetic, can block these nerves and potentially spare motor function (11).

2. Objectives

The primary outcome of this study was the assessment of quadriceps muscle strength following the resolution of spinal anesthesia in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Secondary outcomes included the quality of patient positioning for spinal anesthesia following regional block; pain intensity [measured using Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores] at rest and during movement within the first 24 hours after surgery; total tramadol consumption during the first 24 hours post-surgery; and the incidence of adverse events.

3. Methods

This prospective, randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial was conducted at a single center and included 100 patients diagnosed with hip fractures at Beni-Suef University Hospital between September 2023 and July 2025. All patients were scheduled for hip surgery under spinal anesthesia. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University (FM-BSU) under Identifier FM-BSU REC/06062023/Fakhry, and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT05961436, registered 27/07/2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria comprised male and female patients aged 50 - 80 years with hip fractures, scheduled for hip surgery under spinal anesthesia, and classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades I - III. Exclusion criteria included pre-existing motor weakness, neuromuscular disorders, allergy to local anesthetics, dementia or cognitive impairment, infection at the puncture site, and inability to provide informed consent.

Patients were randomly assigned to two groups: The PENG block group (n = 50) and the FN block group (n = 50). The PENG block group received 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine via ultrasound-guided PENG block, while the FN block group received the same dosage and medication via ultrasound-guided FN block. Randomization was performed using a computer-generated allocation sequence by a researcher not involved in patient care or outcome assessment. Assignments were concealed in opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes, opened only upon the patient's arrival in the operating room. To minimize observer bias, outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation.

3.1. Anesthetic Technique

All patients underwent routine preoperative assessments, including hematological and biochemical tests and cardiac evaluation. The study protocol and the VAS were explained to all participants during the preoperative visit. The VAS is a 10-cm line representing a continuum from 'no pain' (0 cm) to 'worst pain' (10 cm), with scores marked according to the patient's self-reported pain (12). Continuous monitoring of pulse oxygen saturation, noninvasive intermittent blood pressure, and ECG was implemented upon entry to the operating room. Oxygen (4 L/min) was administered via mask. Intravenous fentanyl at a dose of 0.5 µg/kg was used to alleviate anxiety or pain induced by nerve blockade. The VAS scores at rest and during dynamic hip movement were recorded prior to nerve blockade, which was administered with the patient in the supine position.

3.2. Ultrasound-Guided Pericapsular Nerve Group Block Procedure

Following aseptic preparation, patients in the PENG block group were placed in the supine position. Using a low-frequency convex array ultrasound probe (2 - 5 MHz, PHILIPS HD5), the anterior inferior iliac spine was located and the probe moved inferiorly to visualize the pubic ramus. The iliopectineal eminence was identified, and the femoral artery and iliopsoas muscle were visualized centrally. A 22G, 80 mm needle (Pajunk SonoPlex® STIM; Geisingen, Germany) was inserted in-plane, taking care to avoid injury to the FN. Saline (0.5 - 1.0 mL) was injected to confirm the plane and optimize needle placement. Once the needle tip was appropriately positioned, 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was administered, and ultrasound confirmed drug distribution between the pubic ramus and psoas muscle.

3.3. Ultrasound-Guided Femoral Nerve Block Procedure

For the FN block, a linear array high-frequency ultrasound probe (PHILIPS HD5) was positioned over the inguinal crease with the patient supine. The femoral vessels and FN were identified in cross-section; the FN appeared as a spindle-shaped, honeycomb structure lateral to the artery and deep to the fascia iliaca. Using an in-plane technique, a 22G, 80 mm needle (Pajunk SonoPlex® STIM; Geisingen, Germany) was advanced through the fascia iliaca. After careful aspiration at the target, 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected, and ultrasound was used to confirm drug distribution around the nerve.

After a 30-minute period following nerve blockade, VAS scores at rest and during dynamic hip movement were assessed. Both groups then received subarachnoid block as the primary anesthetic. Patients were positioned sitting for spinal anesthesia, and a second anesthesiologist, blinded to block type, assessed positioning quality. Nerve block failure was defined as an inability to sit due to pain or a VAS score ≥ 4. Spinal anesthesia was administered at the L3-L4 interspace under aseptic conditions using 2 - 2.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine (10 - 12.5 mg), maintaining sensory block at the T8-T10 dermatome. Post-operatively, patients were transferred to the PACU until the effects of spinal anesthesia wore off, then returned to the regular ward. Intravenous analgesia was provided post-operatively using nalbuphine 50 mg and ondansetron 8 mg diluted to 100 mL with saline, at a background rate of 4 mL/h. If additional analgesia was required (VAS ≥ 4), intravenous tramadol 1 mg/kg was administered as rescue analgesia.

3.4. Recorded Parameters

- Demographic and baseline health history: Age, sex, BMI, and ASA physical status.

- Anesthetist’s evaluation of patient positioning for spinal anesthesia: Scored as 0 = not satisfactory, 1 = satisfactory, 2 = good, and 3 = optimal.

- Patient acceptance of positioning (yes/no), recorded by a blinded anesthesiologist (acceptance defined as willingness and cooperation in the required position).

- Quadriceps muscle strength, assessed by the Oxford muscle strength grading system (13) after spinal anesthesia resolution in the PACU and at 24 hours post-operatively: Classified as intact (5/5), reduced (1 - 4/5), or absent (0/5), evaluated with the patient seated and knee flexed, then asked to extend against resistance.

- Duration of analgesia: Time from nerve block to VAS ≥ 4

- Vital signs: Heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure, oxygen saturation, compared to baseline and monitored intraoperatively every 10 minutes.

- The VAS scores: Assessed at rest and during dynamic hip movement before and 30 minutes after nerve block, during positioning for spinal anesthesia, and at 0, 30 minutes, 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours after resolution of spinal anesthesia

- Total tramadol consumption in the first 24 hours post-surgery

- Duration of surgery and spinal anesthesia

Complications: Nerve injury, hematoma, delirium, infection at puncture site

3.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome was quadriceps muscle strength after resolution of spinal anesthesia in the PACU. Secondary outcomes were pain intensity (VAS scores) at rest and during movement within 24 hours post-operatively, patient acceptance and positioning quality for spinal anesthesia, quadriceps strength at 24 hours post-operatively, adverse event incidence, and total tramadol consumption in the first 24 hours.

3.6. Sample Size

The primary outcome was quadriceps strength during recovery in hip fracture patients, compared between PENG block and FN block groups. Sample size was calculated for two independent proportions using Fisher’s exact test, with α = 0.05, power = 80%, and group ratio = 1. Based on prior literature (14), 60% of PENG block patients were expected to demonstrate quadriceps strength upon recovery, compared to none in the FN block group. A minimum of 44 participants per group was needed to detect a significant 20% difference. To account for possible dropouts, 50 patients per group were recruited using PS Power and Calculations Software, version 3.1.2 for Windows (William D. DuPont and Walton D., Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs), frequencies, and percentages as appropriate. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for within-group numerical comparisons, using the general linear model (GLM) for repeated measures. Chi-square tests were used for categorical data, with exact tests for expected frequencies < 5. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) version 22 for Windows.

4. Results

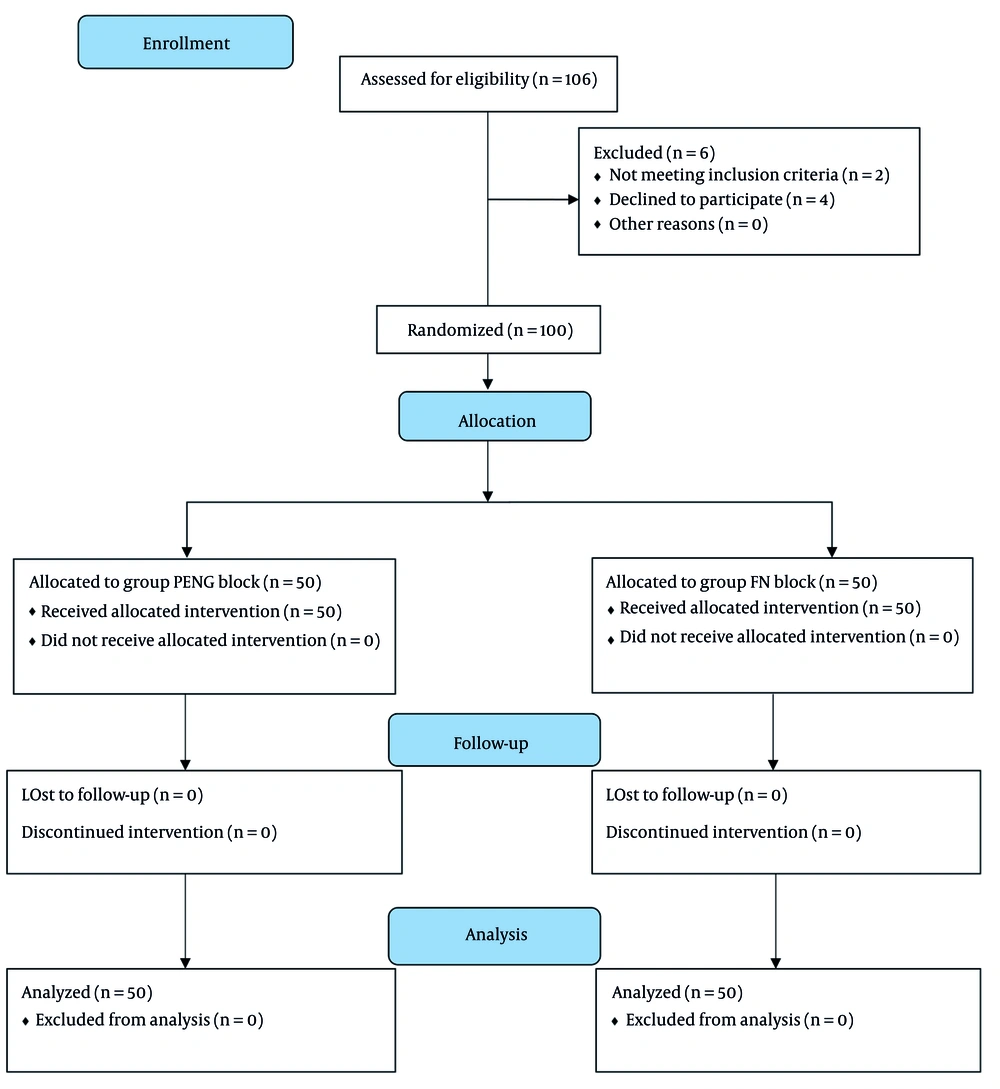

A total of 106 individuals were screened for eligibility; 104 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 100 patients provided informed consent and were randomized into two groups of 50 (Figure 1). No participants withdrew during the study period.

The demographic and operative characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between groups in mean age, sex, BMI, or ASA physical status. Operative variables (surgical duration and duration of spinal anesthesia) and baseline VAS scores (both at rest and during movement) did not differ significantly between groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Characteristics | PENG Block (N = 50) | FN Block (N = 50) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 67.84 ± 5.18 | 67.78 ± 5.59 | 0.956 |

| Gender | 0.542 | ||

| Male | 22 | 19 | |

| Female | 28 | 31 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.80 ± 2.40 | 23.74 ± 2.39 | 0.901 |

| ASA I/II/III | 0.663 | ||

| I | 2 | 4 | |

| II | 34 | 34 | |

| III | 14 | 12 | |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 103.02 ± 10.08 | 103.76 ± 9.67 | 0.709 |

| Duration of spinal anesthesia (min) | 169.26 ± 10.75 | 168.49 ± 11.24 | 0.885 |

| VAS score at rest before the block | 5.64 ± 0.63 | 5.72 ± 0.67 | 0.541 |

| VAS score during movement before the block | 8.52 ± 0.61 | 8.50 ± 0.65 | 0.874 |

Abbreviations: PENG, pericapsular nerve group; FN, femoral nerve; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or No.

b P-value < 0.05 is considered significant, and P-value > 0.05 is considered non-significant.

At 30 minutes after the block, the PENG block group had significantly lower VAS scores at rest and during movement than the FN block group (P < 0.05; Table 2). The PENG block group also demonstrated significantly better quality of patient positioning for spinal anesthesia (2.24 ± 0.52 vs. 2.00 ± 0.54; P < 0.05; Table 2). Patient acceptance of positioning did not differ significantly between groups (P > 0.05; Table 2).

| Variables | PENG Block (N = 50) | FN Block (N = 50) | P-Value | Mean Difference (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS scores at rest after 30 min of block | 2.66 ± 0.52 | 2.92 ± 0.53 | 0.015 | -0.26 (0.468 - -0.052) | - |

| VAS scores during movement after 30 min of block | 3.62 ± 0.53 | 3.90 ± 0.51 | 0.008 | -0.28 (0.486 - -0.074) | - |

| VAS scores at the time of positioning | 2.74 ± 0.49 | 3.00 ± 0.54 | 0.013 | -0.26 (0.463 - -0.057) | - |

| Quality of patient positioning (0 - 3) | 2.24 ± 0.52 | 2.00 ± 0.54 | 0.025 | 0.24 (0.031 - 0.449) | - |

| Patient acceptance for positioning; No. (%) | 0.084 | - | 1.15 (0.979, 1.351) | ||

| Yes | 46 (92.0) | 40 (80.0) | |||

| No | 4 (92.0) | 10 (80.0) |

Abbreviations: PENG, pericapsular nerve group; FN, femoral nerve; RR, relative risk; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless indicated.

b P-value < 0.05 is considered significant, and P-value > 0.05 is considered non-significant.

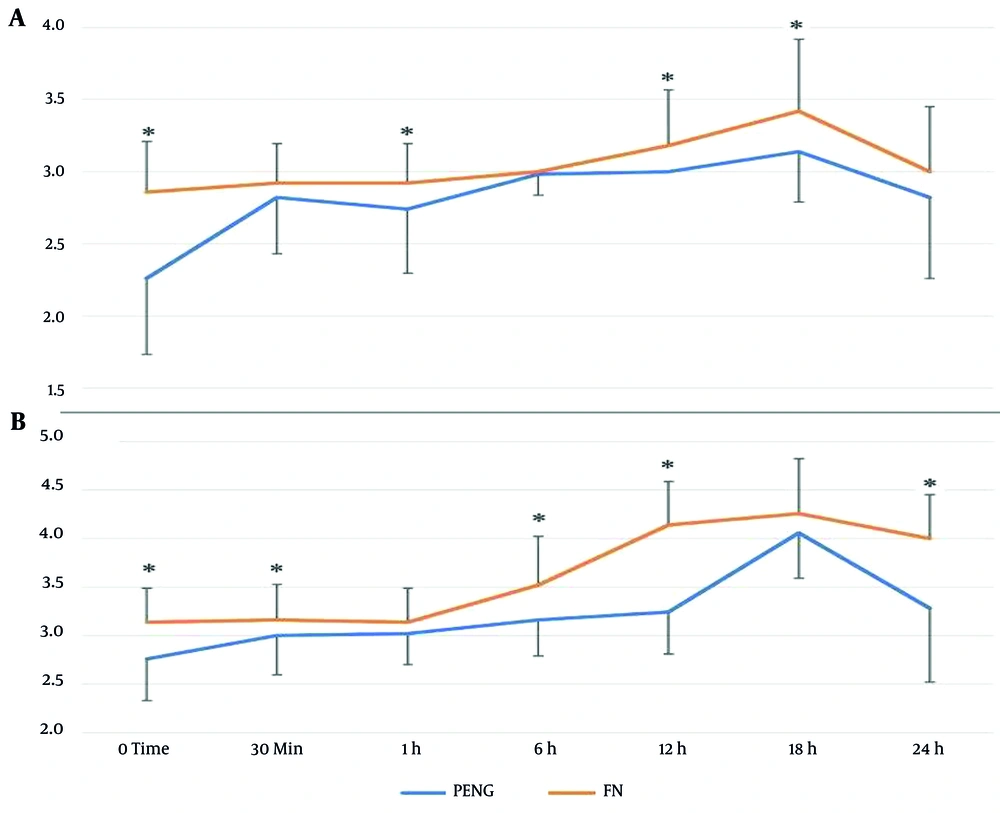

Post-operative VAS scores at rest did not differ significantly between groups at 30 minutes, 6 hours, or 24 hours after spinal anesthesia wore off. However, significant differences were observed at 0, 1, 12, and 18 hours post-spinal anesthesia: The PENG block group reported lower VAS scores at these time points (P < 0.05; Table 3, Figure 2). Over time, the P-value within each group was < 0.001.

| Variables | PENG Block (N = 50) | FN Block (N = 50) | P-Value | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS score at rest | ||||

| Immediately | 2.26 ± 0.53 | 2.86 ± 0.35 | < 0.001 | -0.60 (-0.778 - -0.422) |

| At 30 min | 2.82 ± 0.39 | 2.92 ± 0.27 | 0.140 | -0.10 (-0.233 - 0.033) |

| At 1 h | 2.74 ± 0.44 | 2.92 ± 0.27 | 0.016 | -0.18 (-0.326 - -0.034) |

| At 6 h | 2.98 ± 0.14 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 0.320 | -0.02 (-0.060 - 0.020) |

| At 12 h | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 3.18 ± 0.39 | 0.001 | -0.18 (-0.289 - -0.071) |

| At 18 h | 3.14 ± 0.35 | 3.42 ± 0.50 | 0.002 | -0.28 (-0.451 - -0.109) |

| At 24 h | 2.82 ± 0.56 | 3.00 ± 0.45 | 0.080 | -0.18 (-0.382 - 0.022) |

| P-value over time | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - | - |

| VAS score during movement | ||||

| Immediately | 2.76 ± 0.43 | 3.41 ± 0.35 | < 0.001 | -0.38 (-0.536 - -0.224) |

| At 30 min | 3.00 ± 0.40 | 3.16 ± 0.37 | 0.042 | -0.16 (-0.314 - 0.006) |

| At 1 h | 3.02 ± 0.32 | 3.14 ± 0.35 | 0.076 | -0.12 (-0.253 - -0.013) |

| At 6 h | 3.16 ± 0.37 | 3.52 ± 0.50 | < 0.001 | -0.36 (-0.536 - 0.184) |

| At 12 h | 3.24 ± 0.43 | 4.14 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 | -0.90 (-1.075 - -0.725) |

| At 18 h | 4.06 ± 0.47 | 4.26 ± 0.57 | 0.057 | -0.20 (-0.406 - -0.006) |

| At 24 h | 3.82 ± 0.76 | 4.00 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 | -0.720 (-0.967 - 0.473) |

| P-value over time | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - | - |

Abbreviations: PENG, pericapsular nerve group; FN, femoral nerve; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b P-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant, and P-value > 0.05 is considered non-significant.

During movement, VAS scores did not differ at 1 and 18 hours post-spinal anesthesia, but at 0, 30 minutes, 6, 12, and 24 hours, the PENG block group had significantly lower scores than the FN block group (P < 0.05; Table 3; Figure 2). The P-value over time remained < 0.001 in each group.

The FN block group had a significantly shorter duration of analgesia than the PENG block group (P < 0.05; Table 4). Total tramadol consumption in the first 24 hours did not differ significantly between groups (P > 0.05; Table 4). Quadriceps muscle strength was significantly better in the PENG block group than in the FN block group immediately after spinal anesthesia resolution in the PACU and again at 24 hours post-operatively (P < 0.05; Table 4). The incidence of delirium did not differ significantly between groups (P > 0.05; Table 4). No hematoma, puncture site infection, or nerve injury occurred in either group (Table 4).

| Variables | PENG Block (N = 50) | FN Block (N = 50) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps strength after spinal anesthesia wears off | < 0.001 | ||

| Intact | 32 | 0 | |

| Reduced | 14 | 24 | |

| Absent | 4 | 26 | |

| Quadriceps strength after 24 h | < 0.001 | ||

| Intact | 46 | 28 | |

| Reduced | 4 | 22 | |

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Tramadol consumption in 24 h (mg) | 71.64 ± 9.04 | 76.08 ± 7.00 | 0.118 |

| Duration of analgesia (h) | 23.16 ± 2.10 | 19.92 ± 4.60 | < 0.001 |

| Delirium | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1.000 |

| Hematoma | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Puncture site infection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Nerve injury | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

Abbreviations: PENG, pericapsular nerve group; FN, femoral nerve.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or No. (%).

b P-value < 0.05 is considered significant, and P-value > 0.05 is considered non-significant.

5. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial compared the effects of ultrasound-guided PENG block and FN block on quadriceps muscle strength in patients with hip fractures undergoing surgery under spinal anesthesia. The results demonstrated a statistically significant preservation of quadriceps strength in the PENG block group compared to the FN block group both in the PACU after spinal anesthesia resolution and at 24 hours. Preservation of quadriceps muscle strength in the PENG block group is a key advantage, especially in elderly patients. Avoiding motor blockade — a known drawback of the FN block — enables earlier mobilization and reduces fall risk.

Post-operative VAS scores at rest were significantly lower in the PENG block group at 0, 1, 12, and 18 hours after spinal anesthesia wore off. During movement, the PENG block group also exhibited significantly lower VAS scores at 0, 30 minutes, 6, 12, and 24 hours. Additionally, the PENG block group demonstrated superior patient positioning quality for spinal anesthesia.

Pain and discomfort during positioning for spinal anesthesia are common in hip fracture surgery. Systemic analgesics in elderly patients may cause complications; thus, peripheral nerve blocks remain the gold standard, with the FN block frequently used. The PENG block, which provides motor-sparing analgesia by targeting the articular nerves of the hip, has recently been adopted for positional pain management (15). Several studies emphasize the PENG block’s importance for post-operative pain control and quadriceps motor function recovery in hip fracture surgery. The PENG block selectively targets the sensory branches of the FN supplying the anterior hip capsule, providing effective analgesia without compromising motor function (16).

Kong et al. (17) confirmed the analgesic efficacy of the PENG block in intertrochanteric femur fractures, consistent with these findings. Et and Korkusuz (18) reported earlier mobilization with the PENG block than with the quadratus lumborum block, providing motor-protective analgesia for up to three post-operative hours. Yu et al. (19) noted unintentional quadriceps weakness in 2% of PENG block cases, possibly due to local anesthetic spread to the FN or iliac fascia space from medial or superficial needle tip placement.

Positioning for spinal anesthesia is influenced by pain management, affecting patient comfort and positioning quality (20). In a comparative study by Jadon et al. (21), the PENG block provided better positioning than the fascia iliaca compartment block. Alrefaey and Abouelela (22) found that patients who received the PENG block had lower Ease of Spinal Position Scores and less pain while sitting for spinal anesthesia than controls, concluding that the PENG block is effective for managing positional pain.

Guay and Kopp (23) conducted a meta-analysis showing significant pain reduction within 30 minutes of nerve block. Sahoo et al. (24) similarly found that the PENG block in 20 hip fracture patients with VAS > 5 significantly reduced pain at rest and during 15° straight leg-raise after 30 minutes. Their subsequent study (25) demonstrated significant decreases in VAS scores at 6, 12, and 24 hours post-PENG block, both at rest and during passive movement, supporting the PENG block’s effectiveness for pain relief.

A comparative analysis by Choi et al. (26) found no significant differences between the PENG block and supra-inguinal fascia iliaca compartment block in post-operative pain scores or opioid consumption within 48 hours after total hip arthroplasty under general anesthesia; quadriceps strength also decreased similarly in both groups. Ye et al. (27) reported that ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve blockade did not reduce morphine consumption after total hip arthroplasty compared to local infiltration analgesia and did not provide superior analgesia or enhance hip function. Fahey et al. (28) found no significant differences in adverse events or pain score reduction between experimental and control groups in a pilot study.

The FN is located at or beneath the inguinal ligament and is infiltrated with local anesthetic to block sensation in the anterior upper thigh, patella, and medial lower leg. The FN block is associated with quadriceps weakness, prolonged immobility, and increased risk of post-operative falls. Ghodki et al. (29) reported that only 13% of patients receiving FN block attained normal quadriceps motor function 12 hours post-surgery, while 17% exhibited muscle weakness 24 hours after surgery.

By contrast, the PENG block preserves motor innervation by targeting only the sensory articular branches of the anterior hip capsule, avoiding quadriceps weakness and facilitating rapid post-operative mobilization. In contrast, the FN block affects quadriceps muscle motor innervation, resulting in motor weakness (13).

Our findings of superior immediate post-operative analgesia with the PENG block are consistent with Lin et al. (14), who observed improved pain control in the recovery room and greater quadriceps strength in the PENG block group compared to the FN block, supporting early mobilization. Chaudhary et al. (30) also demonstrated superior analgesia with the PENG block for proximal femur fracture surgery, whereas the FN block group had longer analgesia but reduced quadriceps strength post-operatively. Erten et al. (31) showed that the PENG block provides superior analgesia to the FN block for pain during lateral positioning, hip flexion, and lumbar flexion prior to spinal anesthesia in geriatric hip fracture surgery. Mistry and Sonawane (32) found superior preservation of quadriceps strength in the PENG block group versus the FN block group in femoral fracture patients. Allard et al. (33) reported that while post-operative morphine consumption and pain scores were similar between PENG and FN blocks, quadriceps muscle strength was better preserved in the PENG group, in line with these results. Recent systematic reviews, such as Wan et al. (34), also suggest potential advantages of the PENG block over traditional techniques in hip arthroplasty.

Our findings demonstrate that the PENG block provides superior post-operative analgesia compared to the FN block following hip surgery, with lower VAS scores at multiple time points (both at rest and during movement) and a significantly longer analgesic duration (23.16 ± 2.10 hours vs. 19.92 ± 4.60 hours, P < 0.001). Although tramadol consumption was similar, the PENG block’s motor-sparing effect and improved pain profile underscore its clinical benefit.

The primary limitation of this study is its single-center design and relatively small sample size, limiting generalizability. Future studies with larger cohorts are needed. Another limitation inherent to regional anesthesia trials is the challenge of complete blinding; although the procedural anesthesiologist could not be blinded to block type, the patients, outcome assessor, and data analyst were fully blinded to minimize bias. The study did not include a control group; however, literature suggests that sham or placebo groups do not alter interpretation in regional anesthesia trials. Psychological factors (e.g., anxiety, pain catastrophizing) were not assessed preoperatively, despite their potential influence on pain scores. Follow-up was limited to 24 hours, and time to ambulation or length of hospital stay was not evaluated.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the PENG block provided superior and significantly longer-lasting analgesia, better preservation of quadriceps muscle strength, and improved patient positioning quality during spinal anesthesia compared to the FN block group. There were no significant differences between groups regarding post-operative complications or tramadol consumption.