1. Context

Frailty is primarily defined as a common medical syndrome in the elderly, characterized by reduced physiological reserve, which increases vulnerability to stressors (1). The prevalence of frailty among cardiovascular patients ranges from 10% to 60%, depending on the Frailty Assessment Scale used (2). According to several multicenter studies, 29 - 49% of patients with aortic stenosis (AS) undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) demonstrate characteristics of frailty (3-5). Frailty is observed in up to 63% of elderly individuals undergoing cardiac procedures (6). Therefore, assessing the frailty profile of patients with AS undergoing TAVR is crucial for determining the optimal treatment strategy (7).

Owing to the variety of frailty assessment tools and the absence of a universal definition, the impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery remains a subject of ongoing debate (8-11). Older patients with cardiovascular disease typically present with multiple comorbidities and signs of frailty, necessitating comprehensive risk evaluation for post-surgical adverse outcomes (10, 11). Both European and American guidelines recommend thorough risk assessment with a particular emphasis on frailty indicators in these patients (10, 11). However, these guidelines do not specify a particular tool for frailty assessment.

Most previous studies have shown that frailty is significantly associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes (3-5), including major cardiac events (7, 12), increased hospitalization costs (12, 13), prolonged hospital stays (9, 12-14), and higher mortality rates (9, 12-18) in patients undergoing cardiac surgical procedures. Nonetheless, the influence of frailty on the prevalence of central nervous system (CNS) outcomes remains unclear and contradictory. Some studies have suggested that frailty is associated with a higher incidence of adverse CNS outcomes (13), such as stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA) (19), and postoperative delirium (15, 20, 21), in cardiac surgery patients. Conversely, several studies have reported no significant relationship between frailty and stroke (5, 9, 17, 18, 22-25), delirium (17), or TIA (17). Therefore, frailty assessment is an essential component of risk stratification in candidates for cardiac surgery and may help clinicians minimize postoperative adverse events (2, 7).

2. Objectives

The main objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of neurological adverse outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgical procedures according to frailty status. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis specifically designed to investigate the relationship between frailty status and various CNS outcomes — including stroke, TIA, and delirium — in this patient population.

3. Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. While the study protocol was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO, all methodological steps, including the search strategy, screening, quality assessment, and statistical analysis, were predefined. A completed PRISMA checklist is provided in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File (26). Web of Science, PubMed/Medline, and Scopus were systematically searched for studies published up to October 20, 2024. The following keywords were used for the systematic search: ("Frailty" OR "Frailties" OR "Frailness" OR "Frailty Syndrome" OR "Debility" OR "Debilities" OR "Geriatric Syndromes") AND ("CABG" OR "Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting" OR "Heart Valve Surgery" OR "Aortic Valve Replacement" OR "Mitral Valve Replacement" OR "Heart Valve Repair" OR "Heart Valve Reconstruction" OR "Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass" OR "Off Pump Coronary Artery Bypass" OR "Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery" OR "Aortocoronary Bypass" OR "Heart Valve Annuloplasty" OR "Valvular Annuloplasty" OR "Cardiac Valve Annulus Repair" OR "Cardiac Valve Annular Repair" OR "Heart Valve Annular Repair" OR "Heart Valve Annulus Repair" OR "Cardiac Valve Annular Reduction" OR "Cardiac Valve Annulus Reduction" OR "Cardiac Valve Annulus Shortening" OR "Mitral Annuloplasty" OR "Mitral Valve Annulus Repair" OR "Coronary Bypass Surgery" OR "Surgical Coronary Revascularization" OR "Coronary Grafting" OR "Minimally Invasive Coronary Artery Bypass" OR "Off-Pump Coronary Bypass Grafting" OR "Aortic Valve Repair" OR "Mitral Valve Surgery" OR "Valvular Repair" OR "Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair" OR "Percutaneous Aortic Valve Replacement" OR "Heart Valve Replacements" OR "Coronary Artery Bypass" OR "Coronary Artery Bypass, Off-Pump" OR "Internal Mammary-Coronary Artery Anastomosis" OR "Cardiac Valve Annuloplasty" OR "Mitral Valve Annuloplasty" OR "Heart Valve Prosthesis Implantation" OR "Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement"). All references of the selected studies were manually reviewed to identify additional eligible studies.

3.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

After database searches, all records were merged and duplicates removed using EndNote X21. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. After initial screening, the same reviewers evaluated studies for final inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by two additional authors.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Studies reporting neurological outcomes in adults undergoing cardiac surgical procedures according to frailty status; (2) original studies; (3) English-language articles. Exclusion criteria included review articles, case reports, case series, conference papers, guidelines, letters to editors, commentaries, and animal studies.

3.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the following variables: (1) Study characteristics (publication year, first author, country, design, and quality); (2) patient characteristics (number by frailty status, gender, mean and standard deviation of age, frailty definition and score, comorbidities, surgery type, and total follow-up); and (3) outcomes (number of CNS adverse outcomes by frailty status and mean follow-up after surgery). Disagreements were resolved between the two reviewers.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers assessed the risk of bias. For randomized controlled trials, the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias 2.0 (RoB-2) tool was used. For non-randomized studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate selection, comparability, and outcomes. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and inter-rater agreement was quantified using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ = 0.82), indicating strong agreement (27, 28).

3.5. Operational Definitions

Frailty and neurological outcomes were not uniformly defined across studies. Frailty was assessed using validated tools, including the Clinical Frailty Scale, Edmonton Frail Scale, fried phenotype, Frailty Index, and claims-based frailty scores. Neurological outcomes included postoperative stroke, delirium (assessed using CAM, CAM-ICU, or DSM-based criteria), TIA, and composite cerebrovascular complications as defined by each study. A random-effects model was used to account for conceptual heterogeneity.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA software package version 14 (Stata Corporation LLC., College Station, TX, USA) to calculate the prevalence of each neurological complication. Meta-analyses were stratified by type of surgery. The inverse variance of each study was used as its weight in the pooled proportion. The I2 statistic was used to evaluate between-study heterogeneity, with a threshold of 50%. If the I2 Index exceeded 50%, a random-effects model was employed; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. Forest plots were generated to present findings. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

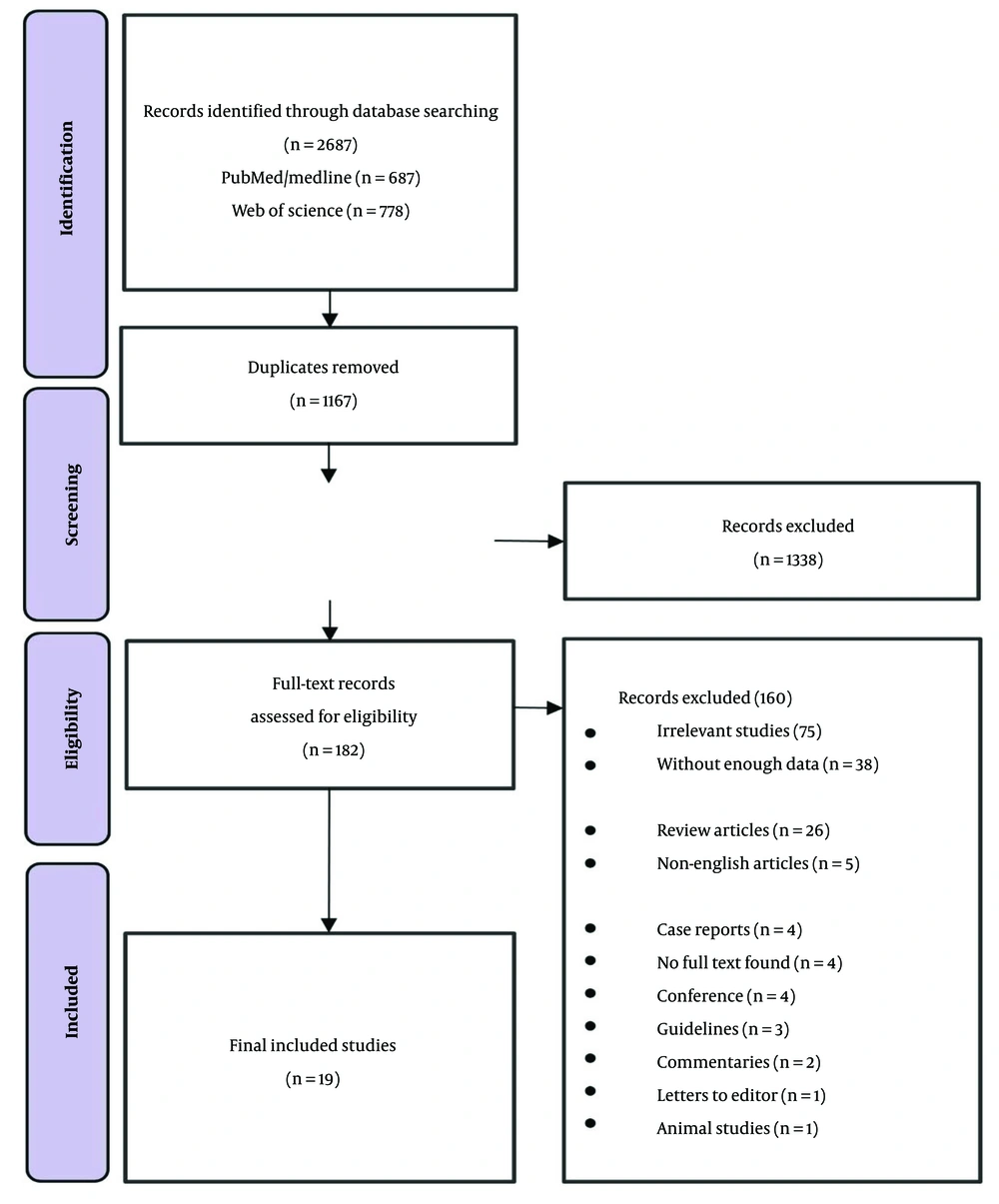

The initial search of the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases yielded 2,687 articles. After removing duplicates, 1,520 articles remained for review. Following title and abstract screening, 182 articles were selected for full-text evaluation, resulting in 19 articles included in the meta-analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

4.2. Study Characteristics

Nineteen articles were included, comprising 2,357,446 patients. Of these, 217,869 were classified as frail, and 2,139,577 as non-frail. The mean age of frail patients ranged from 57 to 87.1 years, while non-frail patients ranged from 58 to 85.4 years. Regarding surgical procedures, 2,293,695 patients underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and 63,388 underwent valve surgeries, including transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or TAVR. For 363 patients, the specific type of surgery was not detailed, though it was indicated as either CABG or valve surgery. Neurological adverse events reported included stroke, delirium, TIA, and cerebrovascular complications.

4.3. Quality Assessment

Most studies utilized a cohort design (n = 12), followed by cross-sectional studies (n = 5), one case-control study, and one randomized controlled trial. The quality assessment results are presented in Table 1.

| Study Characteristics | Study Design | Patient Characteristics | Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, Year, Country and Quality Assessment | Total | Frail | Non-frail | Male; No. (%) | Mean Age | Frailty Score | Type of Surgery | Follow-up Duration | Frail | Non-frail | |||||||

| Frail and non-frail | Frail and non-frail | Stroke | Delirium | TIA | Cerebro vascular Complications | Stroke | Delirium | TIA | Cerebro vascular Complications | ||||||||

| Schofer et al. (19) (2022), Germany, 8 | Cross-sectional | 21430 | 21430 | 0 | 9510 (44.38); NA | 82; NA | HFR score | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 625 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Seoudy et al. (29), (2021), Germany, 8 | Cohort | 953 | 953 | 0 | 389 (40.9); NA | 82.9; NA | GNRI | TAVI/TAVR | 21.1 m | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shibata et al. (30), (2018), Japan, 9 | Cohort | 1613 | 1613 | 0 | 477 (29.5); NA | GNRI ≥ 92: 84.0, GNRI 82 - 9: 85.1, GNRI ≤ 82: 85.4; NA | GNRI | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Strom et al. (25), (2021), USA, 9 | Cohort | 2357 | 2357 | 0 | 1341 (56.9); NA | 82.7; NA | CFIs | TAVI/TAVR | 48 m | 317 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugimoto et al. (31), (2023), Japan, 8 | Cohort | 35015 | 35015 | 0 | 26763 (76.43); NA | Low risk: 74.0, high risk: 75.0; NA | HFRS | CABG | 36 mo | 817 | 433 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yamashita et al. (32), (2021, Japan, 6 | Case-control | 124 | 124 | 0 | 10 (37); NA | 87; NA | CFS | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Barbash et al. (33), (2015), Israel, 7 | Cohort | 1327 | 1327 | 0 | Intermediate 185 (37), high risk 97 (44), low risk 280 (49); NA | 80.84; NA | STS | TAVI/TAVR | 1 mo | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bottura et al. (18), (2019), Brazil, 7 | Cohort | 102 | 88 | 14 | Prefrail: 39 (56), frail: 4 (24); 8 (62) | 57; 58 | Fried Frailty Index | TAVI/TAVR or CABG | 1 mo | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 00 |

| Dautzenberg et al. (17), (2022), Netherland, 7 | Cohort | 431 | 155 | 276 | 135 (49); 56 (36) | 81.7; 80.3 | Groningen frailty indicator | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 8 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 0 |

| Dobaria et al. (13), (2021), USA, 7 | Cohort | 2223497 | 85879 | 2137618 | 57695 (67.2); 1576633 (73.8) | 68.9; 65 | ACG | CABG | Non-frail: 9.0 d, frail: 18.2 d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6321 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38855 |

| Goudzwaard et al. (15), (2018), Netherland, 7 | Cross-sectional | 213 | 213 | 0 | 99 (46.5); NA | 82.03; NA | EFS | TAVI/TAVR | 4 d | 0 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Green et al. (5), (2015), USA, 8 | RCT | 244 | 110 | 134 | 52 (47); 74 (55) | 87.1; 85.4 | The frailty score was calculated based on four markers: Serum albumin, dominant hand grip strength, gait speed, and Katz activity of daily living (ADLs) survey; frail: Score of ≥ 6. | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Holierook et al. (9), (2024), Netherland, 7 | Cross-sectional | 347 | 347 | 0 | High: 17 (40.6), intermediate 87 (42.6), low 51 (46.1); NA | High: 80.2, intermediate: 82.0, low: 80.7; NA | Edmonton Frail Scale | TAVI/TAVR | 4 y | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Huded et al. (22), (2016), USA, 7 | Cohort | 191 | 134 | 57 | Frail: 22 (34), pre-frail: 39 (56); non-frail: 37 (65) | Frail: 83.1, pre-frail: 84.6; non-frail: 78.9 | Fried frailty assessment | TAVI/TAVR | 30 d | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jung et al. (20), (2015), Canada, 7 | Cross-sectional | 133 | 72 | 61 | 48 (66.6); 50 (82) | 73; 68.7 | MFC and SPPB | TAVI/TAVR or CABG | Length of stay in hospital: Non-frail = 6 d, frail = 8 d | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Petrovic et al. (23), (2024), Europe and North America, 6 | Cross-sectional | 1019 | 297 | 722 | 0 (0.00); 0 (0.00) | Frail: 81.4, pre-frail: 82.7; non-frail: 82.5 | Fried criteria | TAVI/TAVR | 1 y | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ad et al. (24), (2016), USA, 7 | Cohort | 168 | 40 | 128 | 24 (61); 101 (79) | 77.6; 73.1 | Cardiovascular Health Study Frailty Index criteria | CABG | 10 y | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nomura et al. (21), (2019), USA, 6 | Cohort | 128 | 113 | 15 | Prefrail: 57 (70), frail: 28 (64); non-frail: 12 (80) | Frail: 73.48, pre-frail: 71.72; non-frail: 69.33 | Fried Frailty Scale | TAVI/TAVR or CABG | 12 mo | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Kundi et al. (34), (2019), USA, 7 | Cohort | 32277 | 32277 | 0 | Transcatheter mitral valve repair: 1941 (51.8), TAVR: 15304 (53.6); NA | Transcatheter mitral valve repair: 80.1, TAVR: 81.5; NA | Johns Hopkins claims-based frailty indicator | TAVI/TAVR | 1 y | 804 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: TIA, transient ischemic attack; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HFR, hospital frailty risk; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index; CFIs, claims-based frailty indices; HFRS, hospital frailty risk score; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; STS, society of thoracic surgeons; ACG, adjusted clinical group; MFS, modified fried scale; SPPB, short physical performance battery; EFS, Erasmus frailty score.

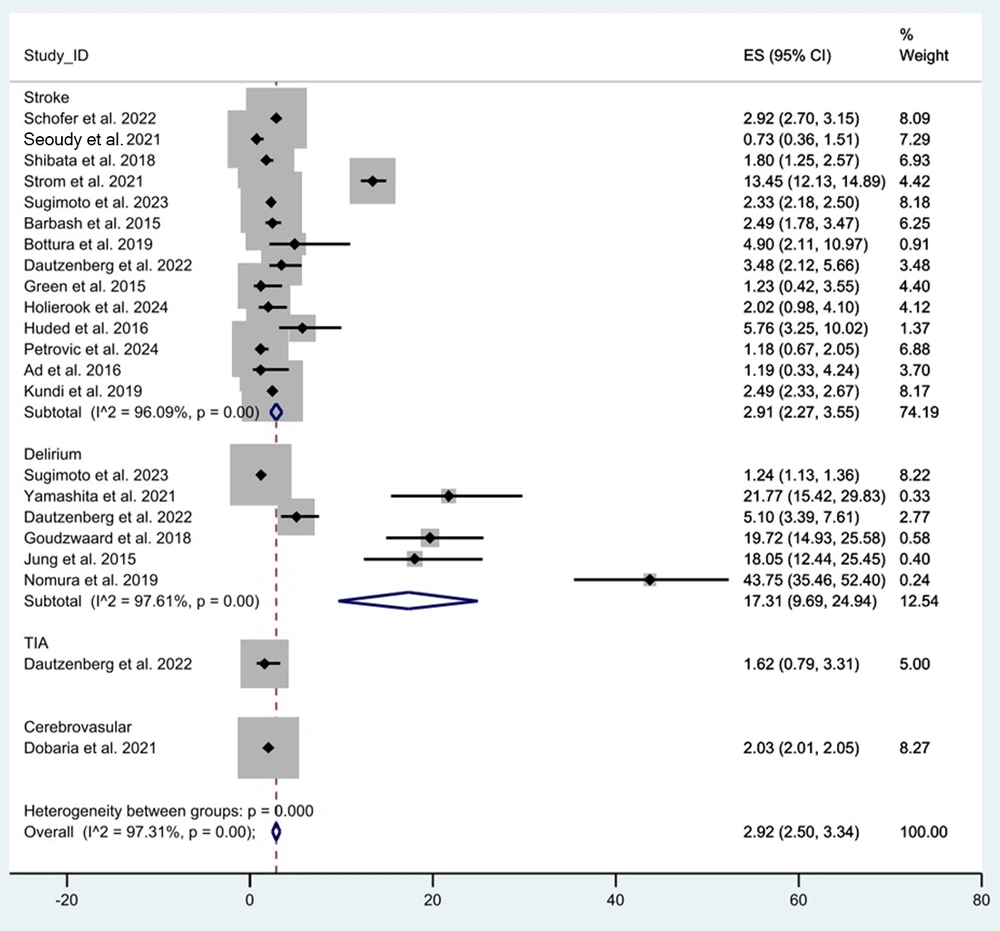

4.4. Neurological Adverse Events

Neurological adverse events occurred in 48,474 patients, with an overall pooled effect size of 2.92% [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.50 to 3.34, P < 0.01, I2 = 97.31; Figure 2]. Among frail patients, the pooled effect size for neurological adverse events was 5.05% (95% CI: 3.87 to 6.24, P < 0.01). Non-frail patients exhibited a lower pooled effect size of 1.81% (95% CI: 1.47 to 2.15, P < 0.01, I2 = 9.1). These results indicate a significantly higher incidence of neurological adverse events in frail patients compared to non-frail counterparts (P < 0.05).

The pooled percentage of neurological adverse events among frail patients varied by surgical procedure. For CABG, the pooled incidence was 3.16% (95% CI: 0.04 to 6.28, P = 0, I2 = 99.91). For heart valve surgery, the pooled incidence was 3.93% (95% CI: 2.97 to 4.89, P = 0, I2 = 96.40).

4.5. Stroke

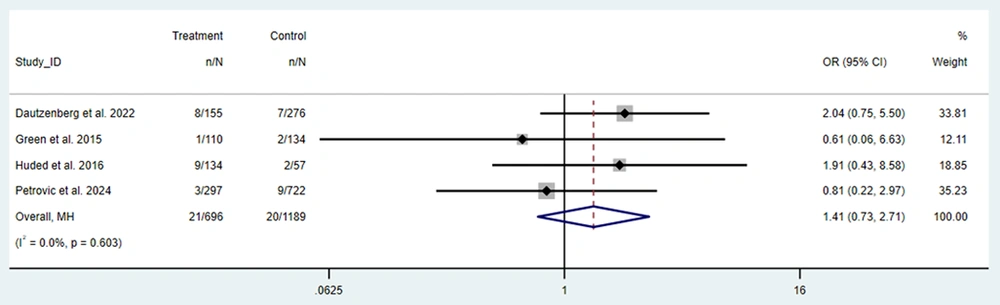

The pooled effect size of stroke among all patients was 2.91% (95% CI: 2.27 to 3.55, P < 0.01, I2 = 96.09; Figure 2). Among frail patients, the pooled effect size was 3.01% (95% CI: 2.33 to 3.69, P < 0.01, I2 = 95.98), compared to 1.47% (95% CI: 0.82 to 2.12, P < 0.01, I2 = 0.00) among non-frail patients. This demonstrates a significant difference in stroke occurrence between frail and non-frail populations (P < 0.05).

By surgery type, the pooled effect size among frail patients was 2.33% (95% CI: 2.17 to 2.49, I2 = 0) for CABG, 3.24% (95% CI: 2.28 to 4.19, I2 = 96.84) for heart valve surgery, and 5.11% (95% CI: 2.11 to 11.87) for patients who underwent either CABG or heart valve surgery. These findings indicate that stroke occurrence varies based on the type of surgery, with heart valve surgery associated with a higher pooled prevalence compared to CABG. Although the pooled prevalence of stroke was higher among frail patients, direct comparison using odds ratios (ORs) in the valve-surgery subgroup (OR = 1.41; 95% CI: 0.73 to 2.71) did not reach statistical significance. Thus, while frailty appears associated with higher crude stroke rates, adjusted comparative evidence does not confirm a statistically significant difference for valve procedures (Figure 3).

4.6. Delirium

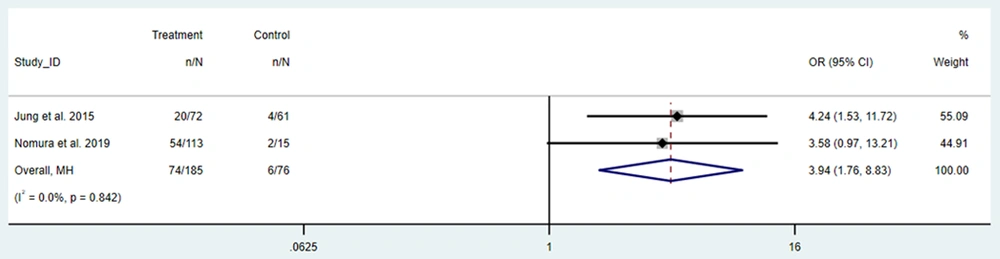

The pooled effect size of delirium among all patients was 17.31% (95% CI: 9.69 to 24.94, P < 0.01, I2 = 97.61; Figure 2). Among frail patients, the pooled effect size was 20.31% (95% CI: 8.82 to 31.80, P < 0.01, I2 = 97.6), compared to 4.44% (95% CI: 2.29 to 6.58, P < 0.01) among non-frail patients. These findings indicate a significantly higher occurrence of delirium among frail populations (P < 0.05).

By surgery type, the pooled effect size of delirium among frail patients was 1.24% (95% CI: 1.13 to 1.36) for CABG, 15.91% (95% CI: 6.08 to 25.75, I2 = 0) for heart valve surgery, and 38.94% (95% CI: 32.06 to 45.82, I2 = 0) for patients who underwent either CABG or heart valve surgery. These findings highlight variability in delirium incidence by type of surgery, with heart valve surgery showing higher prevalence compared to CABG.

Delirium occurrence after CABG or heart valve surgery was also compared between frail and non-frail patients. Frail patients had a higher chance of experiencing delirium, with a pooled OR of 3.94 (95% CI: 1.76 to 8.83, Figure 4).

4.7. Transient Ischemic Attack

The pooled effect size of TIA among all patients was 1.62% (95% CI: 0.79 to 3.31, P = 0.01; Figure 2). Among frail patients, the pooled effect size was 1.29% (95% CI: 0.35 to 4.58, P = 0.15), and among non-frail patients, it was 1.81% (95% CI: 0.78 to 4.17, P = 0.02). The difference in TIA occurrence between the two groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

4.8. Cerebrovascular Complications

The pooled effect size of cerebrovascular complications among all patients was 2.03% (95% CI: 2.01 to 2.05, P < 0.01; Figure 2). Among frail patients, the pooled effect size was 7.36% (95% CI: 7.19 to 7.54, P < 0.01); among non-frail patients, it was 1.82% (95% CI: 1.80 to 1.84, P < 0.01). Thus, cerebrovascular complications were significantly more common in frail patients (P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

Many previous studies have highlighted the significant impact of frailty on outcomes after various procedures (35, 36). Beyond statistical associations, these findings hold important clinical implications. Frail patients have diminished physiological reserves, making them more susceptible to cerebral hypoperfusion, inflammation, and hemodynamic instability during cardiac surgery. Preoperative frailty identification may facilitate individualized anesthetic and surgical management, including optimization of cerebral perfusion, minimization of sedative exposure, and implementation of structured delirium prevention protocols. Therefore, frailty assessment should function not only as a prognostic marker but also as a modifiable perioperative risk factor.

This meta-analysis further underscores that frailty substantially increases the risk of neurological complications — particularly stroke, delirium, and other cerebrovascular events — in patients undergoing cardiac surgeries, including CABG and heart valve procedures (37). The pooled effect size for neurological adverse events was notably higher among frail patients (5.05%) than among non-frail patients (1.81%), demonstrating a clear association between frailty status and increased risk of CNS complications.

Our analysis also reveals that frail patients undergoing heart valve surgery have a higher pooled prevalence of stroke (3.24%) compared to those undergoing CABG (2.33%). This disparity may be attributed to the increased complexity and longer operative times typically associated with valve surgeries, which may impose greater physiological stress on frail patients. Additionally, delirium was markedly more prevalent in frail patients (20.31%) than in non-frail patients (4.44%), emphasizing frailty as a major risk factor for postoperative cognitive disturbances. The OR for delirium occurrence in frail patients after cardiac surgery was significantly elevated at 3.94, suggesting that frail individuals are particularly vulnerable to postoperative cognitive complications, likely due to limited physiological reserves.

Interestingly, our findings for TIA indicate no statistically significant difference between frail and non-frail groups. This may reflect the generally lower incidence of TIA in this population, along with variability in TIA diagnosis and reporting across studies.

These results further emphasize that cerebrovascular complications were more common in frail patients (7.36%) than in non-frail patients (1.82%), highlighting the increased vulnerability of frail individuals. This finding reinforces the need for comprehensive preoperative assessments, as frailty screening can help identify high-risk patients who may benefit from enhanced perioperative care to mitigate neurological risks.

Our meta-analysis provides a comprehensive evaluation of frailty’s impact on CNS outcomes in cardiac surgery patients and highlights the influence of surgery type on the prevalence of specific complications. While previous studies have suggested similar trends, this analysis is among the first to provide pooled data across multiple neurological outcomes, offering a broader perspective on the role of frailty in CNS complications after cardiac surgery.

Because more than 97% of the pooled patient population underwent CABG, surgery-specific conclusions for valve procedures should be interpreted with caution. The smaller valve-surgery sample may limit the precision and generalizability of subgroup estimates.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, frailty significantly increases the likelihood of adverse CNS outcomes — including stroke, delirium, and cerebrovascular complications — among patients undergoing CABG and heart valve surgeries. Our findings underscore the importance of incorporating frailty assessment into preoperative risk stratification for cardiac surgery patients. Identifying frailty can help clinicians implement targeted interventions to reduce CNS risks, such as enhanced monitoring for delirium and stroke during and after surgery. Future studies should aim to standardize frailty assessments and extend follow-up durations to better capture the long-term impact of frailty on neurological health in cardiac surgery patients. Establishing a unified frailty assessment protocol would strengthen clinical decision-making, optimizing treatment pathways and improving patient outcomes.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings:

- Study heterogeneity: Despite using established quality assessment tools such as the NOS and Cochrane RoB-2, variations in study design, sample sizes, and frailty assessment methods led to significant heterogeneity, especially for outcomes such as delirium and TIA.

- Lack of standardized frailty measures: The absence of a universal definition or measurement tool for frailty across studies limits comparability. Different studies employed various scales, possibly affecting pooled effect sizes.

- Variability in surgical details: The types and complexities of cardiac surgeries, including whether procedures were open or minimally invasive, were not consistently reported, potentially impacting the frequency and severity of reported CNS outcomes.

- Limited data on long-term outcomes: While most studies included short-term postoperative outcomes, there was limited follow-up data on long-term CNS outcomes, leaving an incomplete picture of frailty’s impact over time.