1. Background

Cancer, as a chronic and lethal disease, poses a significant threat to the health of both adults and children worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of cancer in children is estimated to be approximately 4% (1). This disease has particularly devastating effects in developing or low-income countries, where around 90,000 children and adolescents lose their lives each year due to cancer (2).

Chemotherapy is recognized as the most common treatment method for children with cancer and is the first choice for physicians due to its high efficacy (3). This treatment involves the administration of cytotoxic drugs that target cancer cells but cannot distinguish between malignant and healthy cells (4).

One serious side effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is oral mucositis (5). This condition leads to severe and debilitating pain, increasing the need for opioid medications. Additionally, patients may require intravenous or enteral nutrition due to difficulties with swallowing. Severe mucositis can result in treatment interruptions and the development of more serious complications (6, 7). Symptoms of this condition include atrophy, swelling, erythema, bleeding, ulceration, and dysphagia, ultimately causing decreased nutrient intake and poor nutritional status (8).

Oral mucositis can also negatively impact patients' speech and may lead to systemic infections as a result of the loss of mucosal integrity (4). A common tool for assessing the severity of mucositis is the World Health Organization Oral Mucositis Grading Scale (WHO-OMGS), which provides clinical criteria for evaluating this condition (9).

Patients undergoing chemotherapy typically experience acute symptoms 3 to 5 days after treatment, with ulcerative lesions generally resolving within two weeks (8). The economic and therapeutic costs associated with mucositis are substantial, including prolonged hospitalization, the need for antibiotics, and parenteral nutrition, all of which significantly increase treatment expenses (6, 7).

Given the serious complications associated with mucositis, its prevention is of paramount importance. At present, various mouthwashes are available for the prevention of mucositis (10). Olive oil, due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, has been investigated in numerous medical studies and contains phenolic compounds and monounsaturated fatty acids that have a positive effect on health (11-13). Additionally, coconut oil is recognized as a health-promoting oil in traditional medicine, with its antimicrobial properties proposed as an effective treatment for mucositis (14).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to investigate and compare the efficacy of topical applications of olive oil and coconut oil in preventing chemotherapy-induced mucositis in children with leukemia. Given the limited research in this area, this study could contribute to the development of preventive strategies and the improvement of patients' quality of life.

3. Methods

This pilot study investigated 100 children aged 1 to 14 years who had been diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and were hospitalized for chemotherapy at Imam Ali Hospital in Zahedan, Iran. The study was conducted over a ten-month period, from February 2024 to December 2024. All patients were classified as high-risk for ALL to ensure that all participants received similar chemotherapy protocols. Inclusion criteria consisted of children aged 1 to 14 years, no previous treatments, the presence of healthy mucosa at the start of treatment, no prior radiotherapy or surgery, no systemic issues or other malignancies, no allergies to olive oil or coconut oil, and no antifungal or antiviral medications received before entering the study. Exclusion criteria included children with unhealthy mucosa upon initial examination. To determine the sample size, Power & Sample Size software was used along with the following formula:

Based on the values of P1 and P2 from the study by Cantekin et al. (15), with α = 0.05, β = 0.8, and d = 0.35, the minimum required sample size for each group was calculated to be 21. To ensure robustness and account for potential dropouts, the number of participants in each group was increased to 25, resulting in a total of 100 participants in the study.

Random selection of patients was achieved through block randomization. Based on the sample size, 13 blocks of 8 were created. After the first patient arrived, one of these blocks was randomly selected, and patients were assigned to groups accordingly. For example, if block DBCA ABCD was chosen, the first patient was assigned to the fourth intervention group, followed by the subsequent groups. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive one of the following interventions to prevent the occurrence of mucositis: Olive oil (Farabkar Company, Rudbar, Iran), coconut oil (Dr. Goerg Organic Coconut Oil, Germany), positive control: Chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.2% NaJu, Iran), and negative control: Normal saline mouthwash (Daru Pakhsh, Iran).

Children and their parents or primary caregivers were instructed to brush their teeth before each application (Figure 1) (16). Interventions were administered by trained and experienced nursing staff every two hours during waking hours. All participants were hospitalized during this period. Trained and experienced nurses applied the intervention agents. A sterile sponge soaked in the assigned substance was applied to the oral cavity, buccal mucosa, and the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue every two hours during waking hours, starting from the first day of chemotherapy for 14 days. Children and their parents were advised to refrain from eating, drinking, or rinsing for half an hour to allow the substances to remain on the mucosal surface (17).

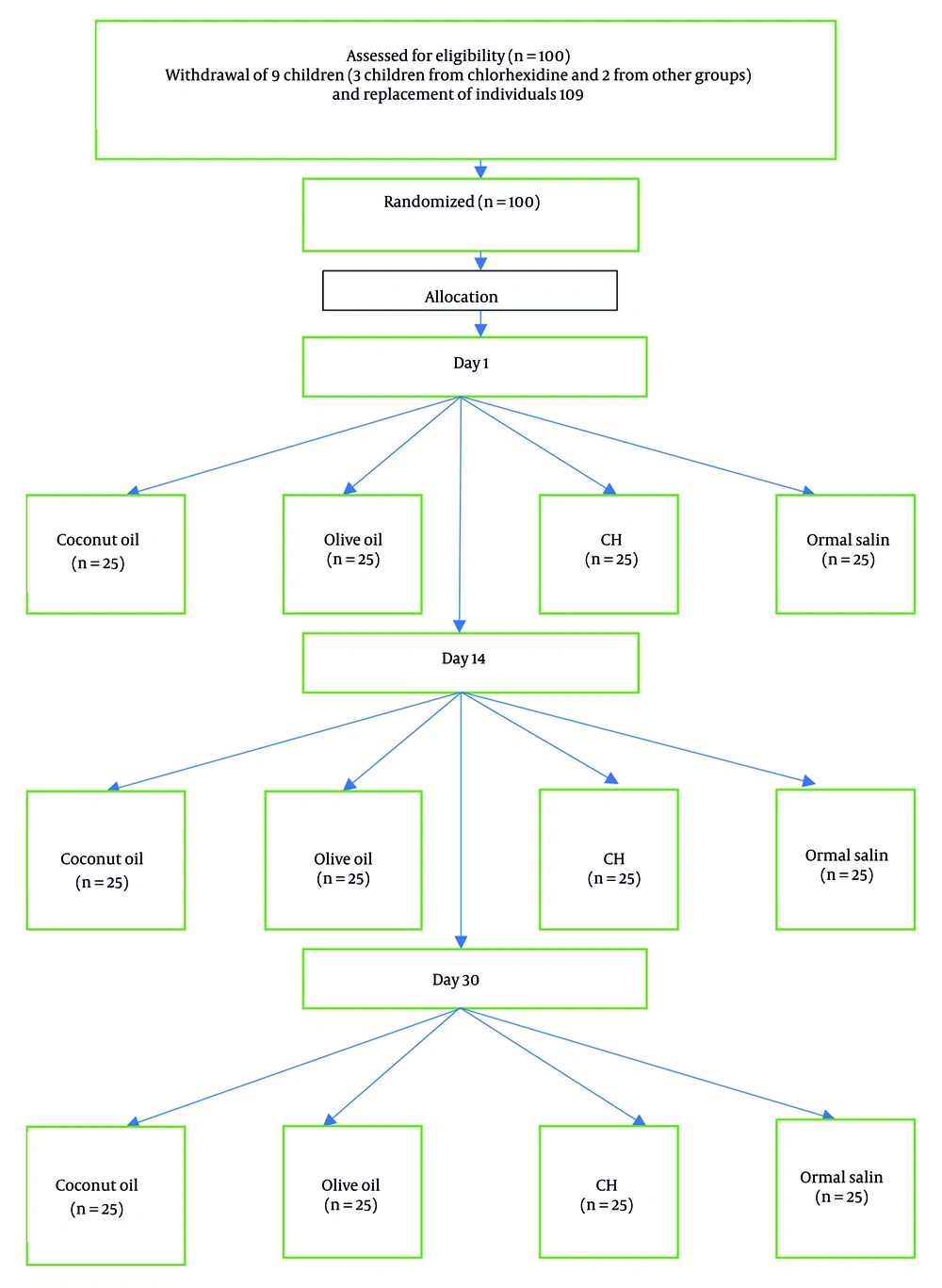

Follow-up assessments were conducted on day 1, day 14, and day 30 by a trained pediatric dentistry specialist who was blinded to the group assignments. The severity of lesions was evaluated using the WHO Scale (18). If a participant declined the researcher’s method, they were allowed to use standard practices in the department. To encourage cooperation among children during the study, rewards were given at each visit. The data analyst was blinded to the group assignments to eliminate bias. Due to uniform baseline scores and evenly distributed attrition, a per-protocol analysis was used. A sensitivity analysis excluding replacement participants was also performed to assess the robustness of findings.

Age and gender distributions across the study groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-squared tests. The chi-squared test was specifically used to compare the distribution of oral mucositis severity between groups. A supplementary post-hoc logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the likelihood of mucositis (grade ≥ 1) at day 14. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, with a significance level set at > 0.05.

After obtaining ethical approval and receiving the clinical trial registration code (IRCT20240126060812N1) and ethical code (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.397), the study's objectives were explained to the parents or legal guardians, and informed consent was obtained.

4. Results

The present clinical trial aimed to compare the effects of olive oil and coconut oil in preventing chemotherapy-induced mucositis in children with leukemia. During the study, 7 patients did not participate in follow-ups, and 2 patients unfortunately passed away due to their illness. To maintain balance across the study groups, nine new eligible participants were enrolled using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. These replacements were randomized using the identical block randomization procedure as the original cohort and were allocated to groups that had experienced attrition.

The participants included 48 girls and 52 boys, with a mean age of 5.6 ± 3.21 years. Chi-squared test results indicated no significant difference in gender distribution among the study groups. Furthermore, ANOVA showed no significant difference in mean age across the groups (P = 0.103).

On the first day, clinical examination revealed that none of the participants had developed mucositis. By the fourteenth day, oral mucositis with varying severities was observed across different groups. In the group that received only normal saline, approximately half of the participants (48%) developed mucositis of severity grade 1, with two cases presenting with severity grades 3 and 4. The mean severity score in this group was 1.16 ± 0.98. In the coconut oil group, 44% of participants experienced mucositis of severity grade 1, with a mean severity score of 0.58 ± 0.52. In the olive oil group, 64% of participants did not develop mucositis. The remainder had mucositis of severity grade 1, with a mean severity score of 0.36 ± 0.48. In the chlorhexidine group, 80% of participants did not develop mucositis; the rest presented with severity grade 1. The mean severity score in this group was 0.20 ± 0.40 (Table 1).

| Groups | Oral Mucositis Severity | Total | Oral Mucositis Severity (Mean ± SD) | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean (Lower-Higher Bound) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Normal saline | 6 (24.0) | 12 (48.0) | 5 (20.0) | 1 (4.0) | 11 (4.0) | 25 | 1.16 ± 0.98 | 0.75 - 1.56 |

| Coconut oil | 13 (52.0) | 11 (44.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 | 0.52 ± 0.58 | 0.27 - 0.76 |

| Olive oil | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 | 0.36 ± 0.48 | 0.15 - 0.56 |

| Chlorhexidine | 20 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 | 0.20 ± 0.40 | 0.031 - 0.36 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

The mean severity of mucositis was compared among the groups (Table 2). The results of the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that mucositis severity varied significantly among the study groups (P < 0.001). The normal saline group exhibited the highest severity of oral mucositis (1.16 ± 0.98), which was significantly higher compared to the chlorhexidine group (0.20 ± 0.40, P < 0.001), with a large effect size (r = 0.583). The normal saline group also showed significantly higher severity compared to the olive oil group (0.36 ± 0.48, P = 0.004), with a moderate effect size (r = 0.468). However, when comparing normal saline to coconut oil (0.52 ± 0.58), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.069), and the effect size was small (r = 0.361).

a Values less than 0.05 indicated a difference between the two groups based on the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction.

When comparing chlorhexidine to olive oil, no significant difference was found (P = 1.000), and the effect size was very small (r = -0.176), indicating that these agents had similar effectiveness in reducing mucositis severity. There was also no significant difference between chlorhexidine and coconut oil, with a P-value of 0.351 and a small effect size (r = 0.299). The comparison between olive oil and coconut oil yielded no statistically significant difference (P = 1.000), and the effect size was very small (r = 0.134), indicating that the difference between olive oil and coconut oil was negligible.

When replacement participants were excluded (n = 91), the Kruskal-Wallis test remained significant (χ2 = 21.214, df = 3, P < 0.001), with results closely mirroring the primary analysis (χ2 = 21.468, P < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that chlorhexidine and olive oil remained significantly superior to normal saline (P < 0.05), while coconut oil showed no significant difference. The pattern of findings was therefore consistent with the main results, with only minor numerical changes (< 2%) that did not affect interpretation. By the thirtieth day, mucositis had resolved in all participants except for one child in the olive oil group, who still had mucositis of severity grade 1.

In a supplementary analysis aimed at simplifying the interpretation of results and defining a clear primary endpoint, mucositis severity on day 14 was selected as the main outcome. Severity was dichotomized into two categories: Grade 0 and grades 1 - 4. Subsequently, binary logistic regression was used to assess the effects of the intervention group on the likelihood of developing mucositis. The results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. Based on the regression table, the difference between the coconut oil and chlorhexidine groups compared to normal saline was statistically significant (Table 3).

| Groups a | B | SE | Wald | df | P-Value | Exp(B) | 95% Confidence Interval for EXP(B); Lower - Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 1.306 | 0.641 | 4.159 | 1 | 0.041 | 3.692 | 1.052 - 12.957 |

| Olive oil | 0.811 | 0.651 | 1.552 | 1 | 0.213 | 2.250 | 0.628 - 8.057 |

| Chlorhexidine | 2.539 | 0.685 | 13.736 | 1 | 0.0001 | 12.667 | 3.308 - 48.504 |

a Reference: Normal saline.

Based on the results, none of the treatment groups had any side effects (Table 4).

| Groups | Tooth Discoloration | Unpleasant Taste | Oral Irritation | Hypersensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Olive oil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlorhexidine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal saline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

5. Discussion

Oral mucositis is a painful complication of chemotherapy and is recognized as one of the most debilitating side effects of cancer treatment. This condition can progress from mild mucosal redness to deep, non-healing ulcers. It causes pain, discomfort, and difficulties with eating or drinking. The prevalence of oral mucositis in patients undergoing chemotherapy varies between 52% and 100% (19). Due to immune system suppression, this complication can have serious and life-threatening consequences. It negatively impacts the quality of life of patients (20).

Management of mucositis primarily involves pain control. This includes using analgesics, local anesthetics, anti-inflammatory agents, and antifungal medications. Despite the understanding of mucositis pathobiology, no definitive preventive interventions are available. Most research has focused on therapeutic methods, with less attention to prevention. This gap is particularly evident in evaluating the effects of various substances in children. Comprehensive comparisons of herbal oils, such as olive oil and coconut oil, in this age group are limited.

Thus, this study assessed the impact of coconut oil and olive oil in preventing oral mucositis compared to chlorhexidine and normal saline. The results indicated that the lowest severity of mucositis was observed in the chlorhexidine and olive oil groups. Chlorhexidine, due to its plaque-inhibiting, antibacterial, and antifungal effects, helps reduce inflammation of the oral mucosa (21). Its bactericidal effects can reduce the colonization of bacteria and fungi, preventing secondary infections (22, 23). Clinical studies have shown that chlorhexidine mouthwash effectively reduces the severity of mucositis and improves oral health in children undergoing chemotherapy (21). However, common side effects of chlorhexidine, such as tooth discoloration and altered taste perception, may reduce patient compliance, especially in children (24, 25).

This study investigated the efficacy of two herbal oils as alternatives to chlorhexidine. The selection of these substances was based on their availability, low cost, and ease of use. The findings indicate that the incidence of mucositis in children undergoing chemotherapy was lower following the use of chlorhexidine and olive oil compared to normal saline. In the olive oil and chlorhexidine groups, 80% and 64% of participants, respectively, remained free of mucositis after two weeks. In contrast, 28% of participants in the normal saline group developed mucositis of severity grade 2 or higher. While chlorhexidine remains superior in reducing the severity of mucositis, olive oil offers a comparable alternative with fewer side effects.

Previous studies have shown that olive oil leads to less severe and later onset mucositis compared to sodium bicarbonate in children undergoing chemotherapy (26). Additionally, the use of olive oil and aloe vera has been effective in managing chemotherapy-induced mucositis (27). Olive oil, due to its anti-inflammatory properties, may help reduce the severity of mucositis (15). According to studies, olive oil can be used topically to manage radiation- or chemotherapy-induced mucositis, reducing severity within ten days (15). A randomized clinical trial also demonstrated that olive leaf extract is effective in managing mucositis (28). The bioactive components of olive oil, such as unsaturated fatty acids and phenolic compounds, possess antioxidant properties that can mitigate tissue damage (29, 30).

In this research, we examined the effects of olive oil and coconut oil on reducing oral mucositis severity. The randomized controlled trial design allowed for a direct comparison of various treatments. The results showed that olive oil and coconut oil significantly alleviated mucositis symptoms, providing greater comfort to patients. However, coconut oil underperformed relative to olive oil and 0.2% chlorhexidine, likely due to several interrelated factors. First, chlorhexidine is well known for its ability to bind to oral tissues and maintain antimicrobial activity for hours after application (31). In contrast, coconut oil, being nonpolar and lacking strong mucosal adhesion, is more susceptible to clearance by saliva or swallowing, which reduces its contact time with ulcerated or inflamed mucosa. Second, while coconut oil is rich in lauric acid, its full antimicrobial potency often depends on conversion to monolaurin or other derivatives. In vitro work shows that coconut oil itself exhibits weaker bactericidal activity compared to monolaurin preparations (32). Thus, in its native oil form, its effectiveness may be limited.

This research not only contributes to the existing knowledge in the management of oral mucositis but can also serve as a foundation for future studies in this field. Our findings guide physicians in selecting more effective and safer treatments for patients undergoing chemotherapy. The decision to use normal saline as the control group was based on its clinical relevance and ethical considerations. Normal saline is commonly used in clinical settings, providing a familiar standard against which our interventions were compared. Its use ensures that participants receive a safe and non-harmful treatment option, rather than a bland placebo that may not provide any therapeutic benefit.

In addition to the efficacy of the treatments, it is important to note that no significant adverse events or local reactions were observed in participants throughout the study. This finding supports the safety of the herbal alternatives, making them a viable option for children undergoing chemotherapy. The goal of this research is to improve the quality of life for patients and reduce the side effects of cancer treatments. We hope that the findings of this study will aid in the development of new treatment protocols that include natural and non-toxic substances.

One of the strengths of this study is its clinical trial design, which effectively allows for the comparison of the effects of olive oil and coconut oil. Additionally, the balanced distribution of gender and age among participants enhances the validity of the findings. This study can serve as a pilot investigation that may assist future research on complementary therapies in cancer patients.

However, this study is subject to some limitations. The relatively small sample size may limit the statistical power to detect true effects. The assessment time points (days 1, 14, and 30) were chosen to strike a balance between clinical feasibility and minimizing patient burden in a pediatric setting. However, this schedule may have resulted in an underestimation of the peak severity of mucositis, which typically occurs between days 7 and 10. Third, the intensive intervention regimen (requiring application every two hours during waking hours), despite being supported by parental training and monitoring, may have challenged perfect adherence, thereby potentially affecting the real-world applicability of the findings. Also, although adherence was high in this inpatient setting, feasibility in outpatient environments may be more challenging due to the intensive dosing schedule. Furthermore, the lack of follow-up for some participants and the unfortunate death of two patients may impact the generalizability of the results, and the logistic regression analysis was post-hoc and not pre-specified.

Another limitation is that the long-term side effects of the topical oils were not evaluated. Moreover, we used commercially available preparations of oils without assessing characteristics such as type of oil preparation, concentration of active compounds, or bioavailability. Future studies should systematically investigate these variables, including standardized or bio-enhanced formulations, dose-response relationships, and patient acceptability, to better define the role of natural oils in the prevention and management of oral mucositis. Finally, the study population was restricted to children with leukemia, which may limit the extrapolation of the results to other age groups or cancer types.