1. Background

Cancer is the leading cause of death among children aged 1 to 14 years. Each year, over 8,500 children are diagnosed with cancer in the United States. In Iran, the incidence rate of childhood cancer is reported as 48 to 112 per one million (1). Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common type of cancer in children, resulting from abnormal proliferation of blood cells in the bone marrow and lymphatic system (2-4). Despite significant advances, no definitive cure exists for cancers. Therefore, the primary goals are to prevent disease progression, minimize treatment side effects, and improve children’s quality of life. Treatments for leukemia include surgery, biological therapies, and chemotherapy. The physical and psychological side effects of these treatments often cause anxiety and distress in children and their families (5). The intensive therapy makes children feel constantly ill and fatigued. These children are prone to infections, which lead to frequent hospitalizations (6).

Chemotherapy is associated with physical complications such as nausea, vomiting, infection, and psychological disturbances (5). Nausea, with or without vomiting, is the most common side effect of chemotherapy (7). These symptoms can severely disrupt the daily activities and quality of life of children with cancer, increasing the risk of psychological consequences such as anxiety and depression, fatigue, and infections (3). Pharmaceutical antiemetic regimens are commonly used to manage nausea and vomiting; however, they may cause serious side effects (8). In addition to medication, non-pharmacological interventions such as herbal remedies, including peppermint and ginger, have shown efficacy in managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) (9).

Ginger, or Zingiber, is considered a safe and effective herbal remedy in traditional medicine (9, 10). Zingiber is available in different forms, including syrup, capsules, oil, and essential extract. Aromatherapy with ginger essential oil is a simple, low-cost intervention, widely accepted and with minimal side effects (9, 10). In Iranian traditional medicine, Zingiber has long been used to relieve discomfort in the head and stomach due to its analgesic, immunostimulant, digestive, and strong antiemetic effects (9).

Aromatherapy is defined as the use of aromatic oils extracted from plants and flowers to treat various conditions (11). Aromatherapy has been used to relieve pain, reduce chemotherapy side effects, promote wound healing, and alleviate respiratory problems (12). Multiple studies have demonstrated the anti-nausea effects of Zingiber. Tadayon Najafabadi et al. found that both Zingiber and ondansetron were equally effective in managing nausea and vomiting during pregnancy (13). Similarly, Amin et al. reported that a combination of ginger and cinnamon was effective in controlling CINV in adults (9). Regarding quality of life, Alijaniranani et al. concluded that orange essential oil aromatherapy improved sleep disorders and ultimately enhanced quality of life in children with leukemia (14).

2. Objectives

While the positive effects of Zingiber have been documented in adults, and various studies have addressed its antiemetic properties, few studies in Iran have specifically evaluated its impact on childhood leukemia. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of Zingiber oil aromatherapy on nausea, vomiting, and quality of life in hospitalized children with cancer receiving chemotherapy at the Pediatric Hematology Ward of Imam Hossein Hospital, Zahedan, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Participants and Setting

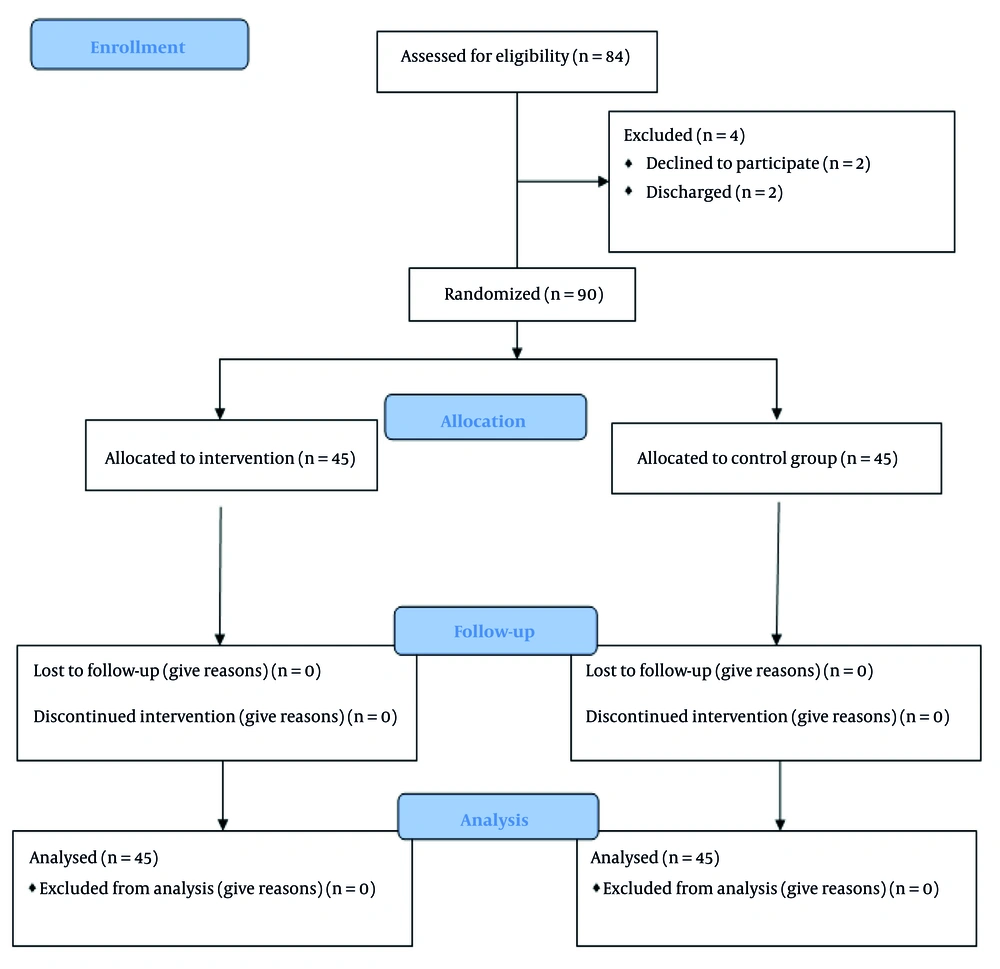

This study was a parallel, single-blind, controlled, randomized trial. Pre- and post-tests were conducted for both the intervention and control groups, before and after the intervention, respectively. This study was conducted and reported in line with the CONSORT 2010 (Figure 1) statement, as recommended by the EQUATOR Network (EQUATOR Network, Schulz et al., 2010). The study was conducted at the Pediatric Hematology Unit of Imam Hossein Hospital in Zahedan, Iran, from January 2022 through December 2022.

Sample size was calculated based on the results of Khalili et al. with a 95% confidence interval and 95% power (15). Using t-tests and the difference between two means formula (α = 5%, d = 2.5, confidence level = 95%, and power = 80%), a minimum sample size of 32 children per group was estimated; however, accounting for potential sample attrition, 45 children were included in each group (total n = 90, intervention group = 45, control group = 45).

3.2. Study Population

Eligible children were selected from hospitalized patients. The inclusion criteria were as follows: School-aged children (6 to 12 years), a confirmed diagnosis of leukemia, intact sense of taste (tested with sugar or salt) and smell (tested with alcohol), and having undergone at least one previous chemotherapy session. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Hemodynamic instability and vomiting without accompanying nausea prior to or during protocol administration.

Simple randomization with envelopes containing cards was used in assigning participants. The numbered cards were placed in sealed envelopes. Participants were given an envelope containing cards with the numbers one (intervention) and two (control). If they chose the number one, they were placed in the intervention group, and if they chose the number two, they were placed in the control group.

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Demographic Questionnaire

This consisted of 9 items, including age, gender, birth order, duration and type of illness, and parental education.

3.3.2. Visual Analog Scale

This self-administered scale measures the severity and frequency of nausea and vomiting. The scale was developed by Davies and Fairbank (1980). A score of zero indicates no symptoms, scores of 1 - 4 indicate mild symptoms, 5 - 7 moderate, 8 - 9 severe, and 10 or above intolerable symptoms. The tool's validity and reliability have been confirmed by Essawy et al., with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9 (3). In our study, the reliability of this scale was reported with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.7.

3.3.3. Pediatric Nausea Assessment Tool

This tool reports the degree of nausea and was developed by Dopovis. It rates nausea on a 1 - 4 scale, with 1 being least and 4 being most severe (7).

3.3.4. Quality of Life Questionnaire

Developed by Bullinger and Ravens-Sieberer to measure quality of life in children with chronic conditions, including cancer (16). The questionnaire features 24 items evaluating physical, emotional, psychological (self-esteem), family, social, and school dimensions, as reported by parents. In addition, 7 items are specific to hospitalization. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8) have been established in Persian populations (17). The reliability of the questionnaire in our study was measured with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.7.

3.4. Study Procedure

The researcher selected the eligible participants from those admitted to the pediatric hematology unit of the hospital. Written and verbal consent was obtained from mothers after adequate explanations to the subjects and mothers. They were assured that the information would remain confidential. First, information from the control group was collected. On the second day of hospitalization, the control group received standard antiemetic medications as prescribed, with no aromatherapy. The frequency and severity of vomiting were measured by the main researcher using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and PeNAT tools. Within 6 weeks after the child's discharge, the Quality of Life Questionnaire was completed again by the child.

The intervention group received standard antiemetic medications plus four drops of Zingiber essential oil (Noshad Pharmaceutical Company, Iran, 37 mL) placed on sterile cotton pads, held 15 cm from the child’s nose and clipped to their collar. Children inhaled the aroma using deep breaths three times, exhaling slowly, for 30 minutes before chemotherapy and before antiemetic administration, and again for 30 minutes after chemotherapy. The severity and frequency of vomiting and nausea were assessed immediately upon occurrence using the VAS and PeNAT tools. Six weeks after discharge, data on quality of life were collected again via telephone follow-up and completed by children.

A single-blind method was performed in our study, as the samples were blinded to the selection of groups. All follow-up data were collected by two researchers. Data analysis was performed by the principal researcher.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical data as frequency and percentage. Independent samples t-test was used to compare groups, and paired t-test was used for within-group comparisons. Covariance analysis was employed to control for pre-test effects. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.259). The trial was registered at the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry (IRCT20201026049150N1). Informed consent was obtained from all parents and children participating in the study.

4. Results

The mean age of children in the intervention group was 8.95 ± 1.99 years and in the control group was 9.08 ± 1.88 years. The independent t-test revealed a statistically significant difference in age between the two groups (P = 0.001). In both groups, 51.12% of children were boys. Other demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

b Chi-square test.

c Independent samples t-test.

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference in nausea severity between groups (t = 1.19, df = 88, P = 0.23). After the intervention, a significant difference in nausea severity was observed (t = 5.32, df = 88, P < 0.001). Paired t-test within each group also showed significant changes in nausea before and after chemotherapy (P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Groups | Intervention | Control | Independent t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 3.17 ± 0.68 | 3.20 ± 0.54 | t = 1.19, df = 88, P = 0.23 |

| After intervention | 2.44 ± 0.91 | 3.15 ± 0.56 | t = 5.32, df = 88, P < 0.001 b |

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b P < 0.05.

Post-intervention, the intervention group's vomiting severity was significantly reduced compared to controls (t = 8.5, df = 88, P < 0.001). The paired t-test in the intervention group before and after chemotherapy also showed a significant reduction in vomiting severity (P = 0.002; Table 3).

| Groups | Intervention | Control | Independent t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | 6.53 ± 2.11 | 8.08 ± 1.68 | t = 2, df = 88, P = 0.24 |

| After intervention | 3.20 ± 2.25 | 7.66 ± 1.83 | t = 8.50, df = 88, P < 0.001 b |

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b P < 0.05.

Regarding quality of life, after the intervention, the intervention group showed significantly higher scores compared to the control group (t = 3.59, df = 88, P < 0.001). Covariance analysis controlled for pre-test effects. Paired t-tests revealed significant improvements in quality of life within both groups pre- and post-intervention (P < 0.001; Table 4).

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effects of Zingiber oil aromatherapy on nausea, vomiting, and quality of life in children with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. The results demonstrated significant differences between the intervention and control groups regarding the severity of both nausea and vomiting after the intervention. Specifically, aromatherapy with Zingiber oil in the intervention group resulted in a notable reduction in both symptoms, indicating its positive impact for children receiving chemotherapy.

These findings align with reports from other researchers who have studied nonpharmacological methods, such as acupressure, peppermint and pennyroyal herbal extracts, and oral Zingiber supplements in combination with antiemetic medications, all of which have shown beneficial effects in reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea. In this regard, a number of researchers consider the use of non-pharmacological methods such as acupressure (18), consuming peppermint and oregano essential oils (19), and consuming Zingiber (20) to be effective in reducing nausea caused by chemotherapy, in addition to pharmacological methods.

Amin et al. investigated the effects of Zingiber and cinnamon consumption on CINV. They concluded that a combination of Zingiber and cinnamon was effective in symptom control. They believe that there is doubt about the effects of ginger in reducing digestive absorption and reducing gastric emptying time and antiemetic effect. Therefore, further research is needed. In their opinion, there is a lot of debate regarding the combination of cinnamon and ginger. This fact is due to the scarcity of evidence, due to the small number of studies and the lack of standardization of samples (9). Modarres et al. compared Zingiber capsules with chamomile capsules for the relief of pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting. They found chamomile oral capsules were significantly more effective than Zingiber and placebo in reducing symptoms of nausea and vomiting caused by pregnancy (21). The reason for the difference between the results of this study and the present study might be due to the variation in the form of Zingiber administration: Oral capsules versus inhaled essential oil, as in our study.

This study also found statistically significant improvements in the quality of life scores in the intervention group both before and after the intervention, as well as within the control group, although the gains were more pronounced with Zingiber oil aromatherapy. This is consistent with the findings of Valizadeh et al., indicating that quality of life in children with cancer is above average and may be impacted by factors such as culture, family support, and medical care (17). Nikkhah Bodaghi et al. found that although Zingiber supplementation improved quality of life in adults with ulcerative colitis compared to controls, this difference was not statistically significant (22). This suggests that further research is needed, especially among different patient populations and age groups. In their study, the effect of Zingiber on adults and patients with ulcerative colitis was investigated. However, the target population of the present study was school-age children (6 - 12 years) with cancer (types of leukemia). Alijaniranani et al. also reported that aromatherapy with orange essential oil improved sleep disturbances and quality of life in children with ALL. One explanation for such results is the effect of aromatherapy on the limbic system, which induces a sense of relaxation and ultimately improves overall well-being (14).

It should be noted that the variations in our results and those of other studies might be due to small sample sizes, the diversity of cancer types and treatment protocols, and differences in the quality and form of the Zingiber product used. Most existing studies have evaluated Zingiber’s effectiveness on a variety of patient groups and cancer types, each with unique protocol-related emetogenic risks, making broad generalizations difficult.

Overall, our results indicate that the mean quality of life score in the intervention group was higher than in the control group, and there was a statistically significant difference between groups. These findings support the use of Zingiber oil aromatherapy in improving the quality of life after chemotherapy among children with cancer.

5.1. Conclusions

Given that nurses play a crucial role in supporting patients before and during chemotherapy, the results of this study can inform the selection of appropriate interventions aimed at reducing nausea, vomiting, and improving the quality of life for children receiving chemotherapy. It is recommended that future studies further examine different forms and dosages of Zingiber supplements, as well as combinations with other essential oils, to facilitate comparison and to address current study limitations. Additional research is also needed to replicate such studies in other pediatric age groups.

5.2. Limitations

The main limitations of this study were the distracting noise in the hospital ward, which could affect children’s attention. To address this, chemotherapy drug administration was scheduled after physicians’ rounds when the ward was less crowded. Furthermore, individual differences in fear and anxiety among children may have influenced the results. Also, for better generalization of the study, studies with larger sample sizes are necessary, as the sample size in this study was limited.