1. Background

Gastroenteritis is one of the most common childhood diseases. Despite improvements in diagnostic and therapeutic methods, the complications and mortality due to acute diarrhea in children under 5 years of age, especially in developing countries, remain significant (1). Despite advances in diagnosis, treatment, and preventive strategies, acute diarrhea continues to be a major global health concern. According to the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reports (2023 - 2024), diarrheal diseases account for approximately 480 million episodes and more than 480,000 deaths annually among children under five years of age, making diarrhea the third leading cause of child mortality worldwide. The burden is disproportionately higher in low- and middle-income countries, where limited access to clean water, sanitation, and adequate nutrition continues to exacerbate disease outcomes (2, 3). Additionally, gastroenteritis is associated with poverty, poor environmental health, and developmental indicators. Deaths from diarrhea reflect a major problem with fluid and electrolyte imbalance, leading to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, vascular instability, and shock (4, 5).

The vitamin D endocrine system plays an essential role in numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes, as vitamin D receptors (VDRs) are expressed in nearly all tissues and cell types throughout the body. Tissues with the highest VDR expression — including the intestine, kidney, parathyroid gland, and bone — are directly involved in maintaining calcium and phosphate homeostasis (6). Beyond its classical role in bone and mineral metabolism, vitamin D also exerts important immunomodulatory effects. By binding to VDRs expressed on various cell types — including keratinocytes, bronchial and gastrointestinal epithelial cells, decidual cells, and trophoblastic cells — vitamin D regulates both innate and adaptive immune responses (7-9). Notably, vitamin D inhibits the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB and reduces the production of key cytokines such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), interleukin-2 (IL-2), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). The widespread distribution of VDRs across immune and non-immune cells underscores vitamin D’s broad biological activity and its role in maintaining immune homeostasis (4, 10).

Based on this, vitamin D plays a critical role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and regulating mucosal immunity. Deficiency in vitamin D can impair epithelial tight junctions, alter gut microbiota composition, and increase susceptibility to gastrointestinal infections. Furthermore, vitamin D influences both innate and adaptive immune responses by enhancing antimicrobial peptide production (such as cathelicidin and defensins) and modulating cytokine profiles to prevent excessive inflammation (11). These mechanisms suggest that insufficient vitamin D levels may predispose children to more severe manifestations of gastroenteritis, including prolonged diarrhea, higher inflammatory markers, and greater dehydration risk (12). Given these biological links, investigating the relationship between vitamin D status and clinical indicators of gastroenteritis is important for identifying modifiable factors that may influence disease outcomes and recovery.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between serum vitamin D levels and the clinical as well as laboratory manifestations of gastroenteritis in pediatric patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted between 2018 and 2019 at Amirkabir Hospital in Arak, Iran. The primary objective was to assess serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D₃] levels in children diagnosed with gastroenteritis and to compare their biochemical and clinical parameters based on vitamin D status.

3.2. Participants

The minimum sample size was determined to be 33 participants per group based on Cohen’s criteria, resulting in a total study cohort of 66 children. Eligible participants were children aged over 2 years diagnosed with gastroenteritis who were admitted to the emergency department or pediatric wards of Amirkabir Hospital. Exclusion criteria included children with underlying medical conditions or those whose parents did not provide informed consent.

3.3. Data Collection

Upon admission, initial blood samples were collected from all participants. Serum was isolated from these primary samples for subsequent 25(OH)D₃ level analysis using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), without requiring additional venipuncture. Patients were then stratified into two groups: Those with sufficient vitamin D (≥ 30 ng/mL) and those with insufficient/deficient vitamin D (< 30 ng/mL).

3.4. Outcome Measures

Key clinical and laboratory outcomes were compared between these two groups. Clinical outcomes included daily frequency of diarrhea and vomiting, dehydration rates, presence of fever, and duration of hospitalization. Laboratory parameters assessed were complete blood count (CBC), urea, serum sodium (Na), serum potassium (K), C-reactive protein (CRP), and stool analysis for white blood cells (WBC) and red blood cells (RBC). Parameters such as arterial blood gas (ABG) values, serum lactate and chloride concentrations, blood pressure, capillary refill time, urine output, and initial fluid bolus requirements were not included in the analysis, as these data were not consistently recorded for all participants. Only clinical and laboratory variables available for all enrolled cases were analyzed to ensure comparability and avoid data inconsistency.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences (Approval ID: IR.ARAKMU.REC.1397.345). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants’ parents or legal guardians prior to any study-related procedures.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis commenced with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess the normality of data distribution. Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while qualitative variables were expressed as counts and percentages [n (%)]. For normally distributed quantitative variables, differences between two groups were analyzed using the independent samples t-test. The Mann-Whitney U test was applied for non-normally distributed quantitative variables. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Scheffé post hoc test was employed. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of participants were stratified by their serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status. The mean age of the abnormal vitamin D group was 5.25 ± 3.17 years, while the normal vitamin D group had a mean age of 4.57 ± 2.69 years. No statistically significant difference in age was observed between the two groups (P = 0.308). Regarding sex distribution, the abnormal vitamin D group comprised 16 males (48.5%) and 17 females (51.5%), compared to 23 males (69.7%) and 10 females (30.3%) in the normal vitamin D group. This difference in sex distribution was not statistically significant (P = 0.132) (Table 1).

| Variables | 25-hydroxyvitamin D | Total | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal | Normal | |||

| Age (y) | 5.25 ± 3.17 | 4.57 ± 2.69 | 4.94 ± 2.91 | 0.308 |

| Sex (M/F); [No. (%)] | 16/17 (48.5/51.5) | 23/10 (69.7/30.3) | 39/27 (59.1/40.9) | 0.132 |

4.2. Clinical Characteristics

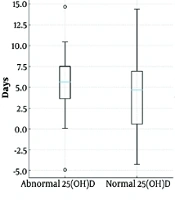

Analysis of laboratory and clinical data revealed no statistically significant differences in the duration of diarrhea (abnormal: 4.79 ± 3.34 days; normal: 5.39 ± 4.67 days; P = 0.791), frequency of vomiting (abnormal: 1.52 ± 1.64 times; normal: 1.88 ± 2.17 times; P = 0.455), or average fever temperature (abnormal: 38.30 ± 1.08°C; normal: 38.05 ± 1.11°C; P = 0.469) between the groups (Table 2Figure 1).

| Variables | 25-hydroxyvitamin D | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal | Normal | ||

| Diarrhea (days) | 4.79 ± 3.34 | 5.39 ± 4.67 | 0.791 |

| Vomiting (times) | 1.52 ± 1.64 | 1.88 ± 2.17 | 0.455 |

| Fever (°C) | 38.30 ± 1.08 | 38.05 ± 1.11 | 0.469 |

| Dehydration | 1.000 | ||

| Moderate | 32 (97.0) | 33 (100) | |

| Severe | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| WBC | 0.389 | ||

| Stool-positive | 27 (81.8) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Stool-negative | 6 (18.2) | 10 (30.3) | |

| RBC | 0.999 | ||

| Stool-positive | 14 (42.4) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Stool-negative | 19 (57.6) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Urea | 0.999 | ||

| Low | 8 (24.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Normal | 24 (72.2) | 23 (69.8) | |

| High | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Na | 0.999 | ||

| Hyponatremia | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal | 32 (97.0) | 33 (100) | |

| K | 0.999 | ||

| Hypokalemia | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Normal | 32 (97.0) | 32 (97.0) | |

| CRP-positive | 27 (81.8) | 19 (57.5) | 0.046 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; Na, sodium; K, potassium; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a Values are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

Furthermore, the prevalence of dehydration was comparable, with a high proportion of moderate dehydration in both groups (abnormal: 97.0%; normal: 100%; P = 1.000). The presence of WBC in stool was observed in 81.8% of the abnormal vitamin D group and 69.7% of the normal group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = 0.389). Similarly, RBC in stool were detected in 42.4% and 39.4% of the abnormal and normal groups, respectively, with no significant difference (P = 0.999). Electrolyte and urea levels also showed no significant variations between the groups. Specifically, the distribution of urea levels (low, normal, high), the incidence of hyponatremia, and the incidence of hypokalemia were statistically similar across both cohorts (all P = 0.999). Also, CRP positivity was significantly more frequent among participants with abnormal (deficient) vitamin D levels compared to those with normal vitamin D levels (81.8% vs. 57.5%, P = 0.046). Conversely, CRP negativity was more common among participants with normal vitamin D levels (42.5% vs. 18.2%). This finding indicates a potential link between lower vitamin D status and higher inflammatory response (Table 2).

5. Discussion

Gastroenteritis is a common childhood illness, and despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, acute diarrhea remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children under five years of age, particularly in developing countries. This study included 66 children hospitalized with gastroenteritis in the pediatric ward of Amirkabir Hospital in Arak. Participants were divided into two equal groups based on serum vitamin D status — normal and abnormal (n = 33 per group) — and their clinical and laboratory parameters were compared.

In the present study, the etiologic agents of gastroenteritis were not routinely identified; therefore, we were unable to determine whether vitamin D deficiency was associated with specific bacterial or viral causes. Previous studies, however, have reported varying associations between vitamin D status and particular pathogens. For example, Bucak et al. observed a link between vitamin D deficiency and rotavirus-positive diarrhea (12), while Gao et al. found an association between low vitamin D levels and Helicobacter pylori infection in young children (13). These findings suggest that vitamin D may influence host susceptibility to certain infectious agents, potentially through modulation of mucosal immunity and antimicrobial peptide expression. Nonetheless, our data did not allow pathogen-specific analysis, and further studies incorporating microbial identification are needed to clarify whether the relationship between vitamin D and gastroenteritis differs according to etiologic pathogen.

Also, our findings did not reveal a significant relationship between serum vitamin D levels and the duration of hospitalization, which contrasts with the results reported by Rahmati et al. (14). In their study of children aged 3 months to 14 years with gastroenteritis, vitamin D supplementation was associated with a shorter hospital stay, independent of age, sex, and dehydration severity. Similarly, Bucak et al. (12) and Gao et al. (13) reported associations between vitamin D deficiency and specific infections, such as rotavirus diarrhea (12) and Helicobacter pylori positivity in children aged 6 to 36 months (13), respectively. In contrast, our study did not identify a specific association between serum vitamin D levels and the causative microorganisms in gastroenteritis.

The etiology of acute gastroenteritis in children is multifactorial, with viral agents such as rotavirus and norovirus being the most common, followed by bacterial pathogens including Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Shigella species (15). Several studies have suggested that vitamin D deficiency may increase susceptibility to such infections by impairing mucosal defense mechanisms and altering gut microbiota composition (14). Vitamin D enhances the expression of antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin and defensins, which play key roles in limiting bacterial and viral replication within the intestinal mucosa. Consequently, low vitamin D levels could predispose children to more severe infections or prolonged illness when exposed to enteric pathogens (3).

Several factors may explain these discrepancies. The relatively small sample size in our study may have limited its statistical power to detect subtle associations. In addition, variations in disease etiology, affected gastrointestinal tract regions, specific pathogens, and demographic factors such as age range, nutritional status, breastfeeding practices, delivery mode, birth weight, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background may all contribute to the differing results observed across studies. Greater matching and multivariate adjustment for these variables in future research could yield more robust conclusions. It is also possible that our findings, derived from Arak — an area with a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency — may differ from those conducted elsewhere, as the influence of vitamin D status on disease course may vary between populations.

Importantly, our study demonstrated a significant association between vitamin D deficiency and CRP positivity (P = 0.046), suggesting that lower vitamin D levels may be related to an enhanced systemic inflammatory response. Vitamin D is known to exert immunomodulatory effects by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines and suppressing hepatic synthesis of acute-phase reactants such as CRP. Thus, the higher frequency of CRP positivity in the vitamin D–deficient group supports the hypothesis that insufficient vitamin D levels may contribute to greater inflammatory activity during acute illness.

However, our results are also consistent with previous studies, such as those by Sari and Korğali (16), who found that vitamin D levels were not affected by acute bacterial infections, and Opstelten et al. (11), who reported no significant association between vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In conclusion, although several studies have suggested a link between vitamin D status and infectious or inflammatory diseases, including gastrointestinal infections, our findings did not demonstrate a significant relationship between vitamin D levels and most clinical or laboratory indicators of disease in children with gastroenteritis. However, because pathogen identification was not routinely performed in our study, we were unable to establish a direct link between specific causative organisms and vitamin D status. Therefore, further prospective studies with larger sample sizes, standardized severity scoring systems, and adjustment for potential confounders are needed to clarify the role of vitamin D in the clinical course and inflammatory response of pediatric gastroenteritis.

5.1. Limitations of the Study

A limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample size (n = 66), which may have reduced the statistical power to detect subtle differences between groups. Although effect size analysis indicated that most associations were small in magnitude, the limited sample may have contributed to the non-significant results. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution, and larger studies are recommended to confirm the observed trends and clarify the clinical relevance of vitamin D status in this population.

Another limitation of this study is the lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors such as nutritional status, seasonal variation in sun exposure, socioeconomic background, breastfeeding practices, and the specific pathogens involved. These variables may influence serum vitamin D levels and disease severity, potentially affecting the observed associations. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as indicative of correlation rather than causation. Future studies with larger samples and multivariate analyses are warranted to clarify these relationships.

Also, disease severity in the present study was not determined by using a standardized scoring system such as the Vesikari scale. The retrospective design and incomplete data precluded the consistent calculation of validated severity scores. This limitation may affect the comparability and precision of severity assessment; thus, future prospective studies should incorporate established scales to ensure standardized outcome measurement.

Another limitation of this study is that data were collected from a single tertiary care center, which may not fully represent the broader pediatric population. Regional differences in nutritional status, infection patterns, and healthcare access could influence the observed associations. Therefore, multicenter studies involving more diverse populations are recommended to improve the external validity of future research.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of several important clinical and biochemical indicators, such as ABG values, serum lactate, chloride levels, and detailed hemodynamic parameters, which could have provided a more comprehensive assessment of gastroenteritis severity.

5.2. Conclusions

Overall, few studies have been conducted on this topic, and most have employed a case–control or cross-sectional design. In the present study, we found no significant association between serum vitamin D levels and most clinical indicators of disease severity; however, CRP levels showed a significant difference between groups (P = 0.046), with CRP positivity being more common among children with insufficient or deficient vitamin D levels. This finding may suggest a potential link between low vitamin D status and increased inflammatory activity. Future studies should include repeated measurements of vitamin D levels and longitudinal follow-up to better evaluate changes over time and clarify potential causal relationships. Additionally, studies with larger sample sizes and standardized severity assessment tools would help strengthen the evidence and further define the role of vitamin D in pediatric gastroenteritis.

![Diarrhea, vomiting and fever in cases with normal and abnormal 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] Diarrhea, vomiting and fever in cases with normal and abnormal 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D]](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31769/a5b8701cbf222ceeff66ecf4d95ba85908b4f9cd/jcp-17-1-166085-i001-preview.webp)