1. Background

Gastroenteritis is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and mild fever, which can lead to severe dehydration, particularly in young children (1, 2). Viral agents, especially noroviruses, are the most frequent causes of this condition, although bacteria, parasites, and toxins can also contribute (3). Transmission typically occurs through contaminated food or water, or direct contact with contaminated objects. Due to its high prevalence among children, especially those under six months of age, gastroenteritis represents a significant public health concern (1, 4).

Gastroenteritis is a major cause of diarrhea-related mortality in children. Estimates indicate that approximately two million child deaths occur annually worldwide due to infectious diarrhea and dehydration, particularly in developing countries with limited access to healthcare (5). Symptoms of the disease usually appear suddenly and include nausea, vomiting, and watery diarrhea, along with cramping abdominal pain that comes on quickly and intensely. A person may also experience chills, headache, low-grade fever, and muscle aches, all of which can be accompanied by a general feeling of fatigue and extreme weakness (1).

The goals of treatment for acute gastroenteritis are to prevent dehydration, treat dehydration when it occurs, and reduce the duration and severity of symptoms. There are many guidelines for the treatment of acute gastroenteritis, largely based on expert consensus (6). Oral rehydration solutions and, in severe cases, intravenous fluids constitute the cornerstone of treatment. Antiemetic drugs, such as ondansetron, may be used to improve fluid tolerance, whereas antibiotics are generally of limited value in viral cases (5). While these measures are effective in managing dehydration, they have limited impact on reducing symptom severity and shortening disease duration, highlighting the need for complementary therapeutic approaches (7).

Given the limitations of conventional treatments, traditional medicine and herbal remedies have gained attention for diarrhea management (8). Several other studies have also reported that many plant species belonging to the Boraginaceae family, such as Cordia myxa, Cordia rothii, Cordia americana, and Carmona retusa, have therapeutic uses for diarrhea in various communities (9). One of the recommended medications to reduce the severity and speed up the healing process is C. myxa (Boraginaceae) (10-12). Cordia myxa (Boraginaceae), known as “Sepestan,” is a widely used medicinal plant in traditional medicine in Iran and the Middle East (13).

Its fruit is rich in mucilage, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, and antioxidant compounds, and various experimental and animal studies have reported its anti-inflammatory, antidiarrheal, antihistaminic, and analgesic effects (11, 14, 15). Ethnobotanical and phytochemical studies have demonstrated that species of the Boraginaceae family, particularly C. myxa, with antioxidant and cytotoxic activity, are effective in managing oxidative stress-induced disorders, such as diarrhea (16).

Additionally, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of this plant have been documented in animal models of colitis and other gastrointestinal disturbances. The mucilaginous and antioxidant compounds in C. myxa fruit appear to reduce gastroenteritis symptoms by coating the intestinal mucosa, decreasing inflammation, and improving the immune defense system (14, 17).

However, clinical studies investigating the role of C. myxa syrup in reducing the severity and duration of diarrhea in children remain very limited.

2. Objectives

The present study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of C. myxa syrup in reducing the severity and duration of diarrhea in hospitalized children with gastroenteritis.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

In this double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial study, 140 patients with gastroenteritis aged 1 - 8 years referred to Abuzar Hospital in Ahvaz, Iran in 2024 were enrolled.

Inclusion criteria were patients with gastroenteritis aged 1 - 8 years, gastroenteritis with symptoms occurring in ≤ 24 hours, no prior medication, absence of severe dehydration or abnormal stool findings, and completion of an informed consent form by parents. Patients with concurrent illnesses, suspected surgical conditions, non-adherence to the study protocol, or intolerance to the study medication were excluded.

The sample size was calculated assuming a 25% relative reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group, with a significance level of 0.05 and 80% power (G*Power version 3.1). The final sample included 70 participants per group (Total = 140 patients).

These eligible patients were divided into two equal intervention groups (receiving C. myxa syrup) at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day and the control group (receiving the placebo). Syrup and placebo were matched in appearance, color, and taste to maintain double-blinding. A questionnaire was designed to collect information. In this questionnaire, the stool consistency was assessed at four levels: "Normal (formed stool)", "loose (despite the stool being unformed, no clear water is visible in it)", "watery (stool with watery backgrounds with harder parts)", and "very watery (only water in the stool)" with a score from 1 to 4, and stool volume was assessed at three levels: "Low", "moderate", and "high" with a score from 1 to 3.

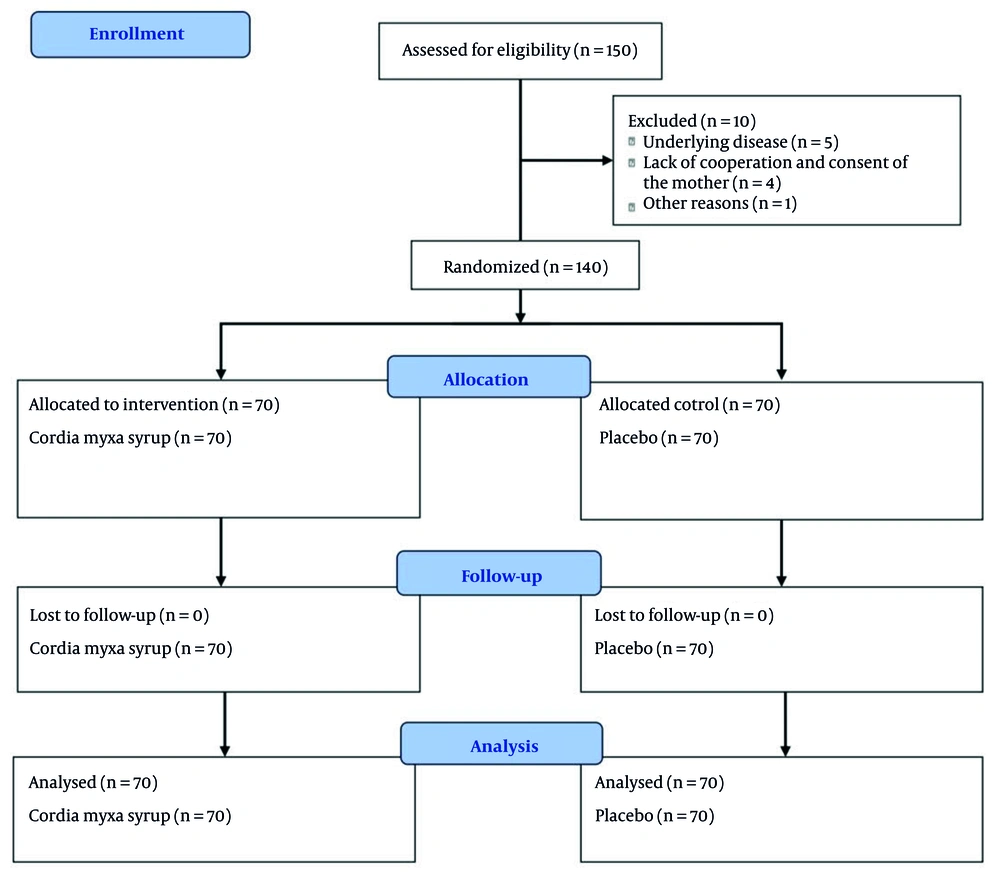

Before starting the study, the children’s parents were familiarized with the precise definitions of each level of stool consistency and volume. The number of diarrhea episodes was recorded as quantitative data (number of episodes in 24 hours). In addition, clinical symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, restlessness, fever, chills, and sweating were monitored and recorded by the researchers on the first, second, third, and seventh days after the start of treatment. Both the patients (and their parents) and the researchers were blinded to the assigned treatment groups. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

3.2. Randomization and Allocation to Intervention and Control Groups

A simple randomization method was used in our study. Each patient had the same chance to join any group. A random number generator or random number table was employed. We selected numbers from the random number chart. The intervention groups (receiving C. myxa syrup) would be labeled 1 - 70, while the control group (receiving the placebo) would be assigned numbers 71 - 140. We began at a certain spot in the arbitrary number chart, placing participants in the initial group if the number fell within 1 - 70 and in the control group if it fell within 71 - 140. Any numbers outside of these ranges were disregarded as we continued assigning all patients.

3.3. Preparation of Cordia myxa Syrup

Preservatives were added to distilled water and the resulting solution was heated to 70°C, then sucrose was added and stirred until completely dissolved, and the solution was cooled to room temperature. The required amount of extract was dissolved in dilute citric acid and added to the solution after cooling. The mixture was brought to a final volume of 100 mL by adding 70% sorbitol solution, glycerin, and distilled water. Finally, the prepared product was evaluated for organoleptic properties (including color, odor, taste, and appearance) as well as physicochemical properties such as the amount of active ingredient and viscosity. In addition, microbial control of the syrup was carried out by culturing the sample on standard media (Nutrient Agar, MacConkey Agar, and Sabouraud Dextrose Agar) to examine the total microbial load, the presence of indicator bacteria, and fungi/molds.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software Version 26. Mean ± SD and number (percentage) were used to indicate quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Between-group comparisons were performed using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Longitudinal changes were analyzed using repeated measures models and generalized estimating equations (GEE). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The mean age of participants was 27.53 ± 18.81 months, with an age range of 1 to 8 years. The duration of diarrhea ranged from 1 to 2 days. Comparison of the mean diarrhea duration between the intervention and control groups revealed that administration of C. myxa syrup significantly reduced diarrhea duration. The mean duration in the intervention group was 3.91 ± 1.15 days, compared to 4.71 ± 1.47 days in the control group (P < 0.001). Evaluation of diarrhea severity based on the number of bowel movements per day at different time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 hours, and day 7) showed that participants in the C. myxa syrup group experienced fewer bowel movements at most time points. At 72 hours after treatment initiation, the mean number of bowel movements was significantly lower in the intervention group compared to the control group (P = 0.023). More details are provided in Table 1.

| Time/ Frequency | Group a | CI (95%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Control | Cordiamyxa Syrup Group | |||

| At admission | (1.64 - 2.52) | 0.001 | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 1 (0.70) | 16 (11.40) | ||

| 4 - 5 times | 14 (10.00) | 12 (8.60) | ||

| 6 - 10 times | 55 (39.30) | 42 (30.00) | ||

| Number of stools (24 h) | (1.59 - 2.49) | 0.49 | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 39 (27.90) | 32 (22.90) | ||

| 4 - 5 times | 24 (17.10) | 29 (20.70) | ||

| 6 - 10 times | 7 (5.00) | 9 (6.40) | ||

| Number of stools (48 h) | (0.97 - 1.61) | 0.089 | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 47 (33.60) | 57 (40.70) | ||

| 4 - 5 times | 21 (15.00) | 13 (9.30) | ||

| 6 - 10 times | 2 (1.40) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Number of stools (72 h) | (0.86 - 1.26) | 0.023 | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 59 (42.10) | 67 (47.90) | ||

| 4 - 5 times | 11 (7.90) | 3 (2.10) | ||

| 6 - 10 times | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Number of stools (96 h) | (0.94 - 1.11) | 0. 24 | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 68 (48.60) | 70 (50.00) | ||

| 4 - 5 times | 2 (1.40) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| 6 - 10 times | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Number of stools (day 7) | (0.96 - 1.07) | - | ||

| 1 - 3 times | 70 (50.00) | 70 (50.00) | ||

a Values are presented as No. (%).

Based on the tests of Between-Subjects Effects, the group variable (Cordia myxa group vs. control group) had a significant effect on diarrhea severity (F = 9.777, P = 0.002), whereas age and sex showed no significant effects (Table 2).

| Variables | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Sum of Squares | F-Value | Partial Eta Squared | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.103 | 1 | 0.103 | 0.500 | 0.003 | 0.481 |

| Gender | 0.060 | 1 | 0.060 | 0.290 | 0.003 | 0.591 |

| Group (Intervention/control) | 2.012 | 1 | 2.012 | 9.777 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| Error | 27.575 | 134 | 0.206 | - | - | - |

Assessment of stool consistency over time indicated that participants in the C. myxa syrup group experienced a faster improvement. Within the first 24 hours, a higher proportion of patients in the intervention group had “normal” stools compared to the control group, which predominantly exhibited “watery” stools (P < 0.001). This pattern of improvement continued at 48 and 72 hours, and by day 7, both groups had achieved normal stool consistency (Table 3).

| Variables | Group a | CI (95%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cordiamyxa Syrup Group (n = 70) | Control Group | |||

| Stool consistency upon arrival at admission | (3.36 - 4.01) | 0.119 | ||

| Loose | 4 (2.90) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Watery | 13 (9.30) | 12 (8.60) | ||

| Very watery | 53 (37.90) | 58 (41.40) | ||

| Stool consistency upon arrival 24 h | (2.03 - 3.01) | < 0.001 | ||

| Natural | 17 (12.10) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Loose | 35 (25.00) | 22 (15.70) | ||

| Watery | 17 (12.10) | 32 (22.90) | ||

| Very watery | 1 (0.70) | 16 (11.40) | ||

| Stool consistency upon arrival 48 h | (1.40 - 2.17) | < 0.001 | ||

| Natural | 46 (32.90) | 15 (10.70) | ||

| Loose | 22 (15.70) | 45 (32.10) | ||

| Watery | 2 (1.40) | 10 (7.10) | ||

| Stool consistency upon arrival 72 h | (1.03 - 1.54) | < 0.001 | ||

| Natural | 67 (47.90) | 42 (30.00) | ||

| Loose | 3 (2.10) | 28 (20.00) | ||

| Stool consistency upon arrival 96 h | (0.99 - 1.00) | - | ||

| Natural | 70 (50.00) | 70 (50.00) | ||

| Stool consistency upon arrival day 7 | (0.99 - 1.00) | - | ||

| Natural | 70 (50.00) | 70 (50.00) | ||

a Values are presented as No. (%).

Statistical analysis of stool consistency demonstrated that the type of treatment had a significant effect on improvement in stool consistency (F = 39.803, P < 0.001). Additionally, sex was also a significant factor (P = 0.041), whereas age showed no remarkable effect (Table 4).

| Variables | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Sum of Squares | F-Value | Partial Eta Squared | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.001 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.00 | 0.96 |

| Gender | 1.28 | 1 | 1.28 | 4.24 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Group (intervention/control) | 12.08 | 1 | 12.08 | 39.80 | 0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Error | 40.69 | 134 | 0.304 | - | - | - |

Assessment of stool volume revealed a significant difference between the two groups. Over time, participants receiving C. myxa syrup experienced a more rapid reduction in stool volume. Specifically, at 24 and 48 hours after treatment initiation, the proportion of patients with “low” stool volume increased significantly, whereas the control group maintained a higher proportion of patients with “high” stool volume (Tables 3 and 4). Results from the Tests of Between-Subjects Effects indicated that only the treatment group had a significant effect on stool volume (F = 49.929, P < 0.001), while age and sex prior to intervention had no significant impact on this variable (Table 5).

| Time/ Frequency | Group a | CI (95%) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cordia myxa Syrup Group (n = 70) | Control Group | |||

| Volume of stools (at admission) | (2.78 - 3.19) | 0.001 | ||

| Low | 1 (0.70) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Medium | 10 (7.10) | 1 (0.70) | ||

| High | 59 (42.10) | 69 (49.30) | ||

| Volume of stools (24 h) | (1.86 - 2.59) | 0.000 | ||

| Low | 28 (20.00) | 1 (0.70) | ||

| Medium | 39 (27.90) | 43 (30.70) | ||

| High | 3 (2.10) | 26 (18.60) | ||

| Volume of stools (48 h) | (1.46 - 2.09) | 0.000 | ||

| Low | 14 (10.00) | 45 (32.10) | ||

| Medium | 56 (40.00) | 24 (17.10) | ||

| High | 1 (0.70) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Volume of stools (72 h) | (1.16 - 1.72) | 0.000 | ||

| Low | 37 (26.40) | 64 (45.70) | ||

| Medium | 33 (23.60) | 6 (4.30) | ||

| Volume of stools (96 h) | (0.91 - 1.13) | 0.60 | ||

| Low | 66 (47.10) | 70 (50.00) | ||

| Medium | 4 (2.90) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Volume of stools (day 7) | (0.96 - 1.07) | - | ||

| Low | 70 (50.00) | 70 (50.00) | ||

a Values are presented as No. (%).

5. Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of C. myxa syrup (Sepestan) on children with diarrhea and demonstrated a significant reduction in symptom severity. The mean age of participants was approximately 2.25 years. Children in the intervention group showed a significant decrease in diarrhea duration, and the number of bowel movements was reduced after 72 hours compared to the control group, with statistically significant differences. Demographic variables such as age did not significantly influence the measured outcomes, while gender affected stool consistency but not stool volume. These findings suggest that C. myxa syrup may serve as an effective therapeutic option for alleviating diarrhea symptoms in children.

Some studies have indicated the effects of the plant Sepestan, such as anti-diabetic, antipyretic, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiulcer, immunomodulatory, and anticancer properties. In addition, the plant has been used as a treatment for stomach pain, asthma, mouth ulcers, bronchitis, diarrhea, cardiovascular diseases, rheumatism, and tooth decay (18, 19). Our study examined the antidiarrheal effects of C. myxa syrup (Sepestan). Our results align with previous studies on the effect of C. myxa (20-22). Larki et al. reported that the plant is rich in alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, and phenolic compounds, which exhibit anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. These compounds can reduce gastrointestinal inflammation and improve digestive function, which may explain the observed decrease in diarrhea duration and severity in our study (23).

Bernard et al. (22) have investigated the antibacterial effects of compounds extracted from the root of Sepestan in their study and have shown that these compounds are active against Salmonella typhi, one of the main causes of infectious diarrhea. Their findings are consistent with our study, as the reduction in the duration of diarrhea in the intervention group could be due to the inhibition of the growth of pathogenic microbes and the reduction of inflammation caused by the infection (22). In addition, Al-Snafi also reported that C. myxa has anti-inflammatory and protective properties for the gastrointestinal tract (21). This finding is also mechanistically consistent with our study, as reducing gastrointestinal inflammation can have a direct effect on reducing the severity and duration of diarrhea. Less inflammation leads to reduced fluid secretion in the intestine, resulting in a decrease in stool volume and frequency, which was also observed in our study.

Abdel-Aleem et al. reported that Sepestan contains high levels of antioxidant compounds such as phenols and flavonoids, and that these compounds can help reduce oxidative stress in the body (20). Although this study did not directly investigate the effect of these compounds on diarrhea, since inflammation is an important factor in prolonging the duration of diarrhea, the antioxidant properties of this plant could play an important role in reducing the duration of diarrhea. Therefore, this study also indirectly confirms the findings of our study.

Despite the traditional use of Sepestan for gastrointestinal disorders, Singh et al. pointed out the lack of rigorous clinical evidence. Most prior studies were observational or lacked controlled clinical trial designs. They argued that many studies conducted on this plant lacked rigorous clinical design and its effects were mainly based on experimental data rather than controlled clinical trials (24). Our study addresses this gap, demonstrating significant clinical improvements in diarrhea symptoms with Sepestan syrup, likely due to its anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties. These concerns from Singh et al. are addressed by our study, as our study was conducted clinically and a statistically significant reduction in diarrhea symptoms after consuming C. myxa syrup was reported. This discrepancy could be due to differences in study methodology; our study used more rigorous methods and a control group, while Singh et al.’s study was based on a literature review and, as a result, was unable to directly assess the intervention’s effect on patients (24).

Limitations of this study include the single-center nature of the study, restriction to a specific age group, and lack of long-term follow-up. Factors such as pathogen type, baseline disease severity, and nutritional or environmental influences were not fully controlled. Future research should include larger sample sizes, broader age ranges, and investigations into different causative agents of diarrhea (viral vs. bacterial) to elucidate the mechanisms of Sepestan’s effects. Also, further multicenter studies with longer follow-up periods and higher dosage of C. myxa syrup are recommended to assess sustained efficacy and potential side effects.

5.1. Conclusions

Cordia myxa syrup (Sepestan) significantly reduced diarrhea duration, frequency, and improved stool consistency in children. Its effects are likely mediated through anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant mechanisms. While our findings support its potential as a complementary treatment for pediatric diarrhea, further rigorous clinical trials are warranted to establish its efficacy across different patient populations and conditions.