1. Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a chronic, autosomal recessive multisystem disorder characterized primarily by pulmonary involvement. Mutations in the CFTR gene lead to defective chloride ion transport and reduced mucosal hydration, which predispose patients to persistent respiratory infections, airway obstruction, inflammation, and progressive lung damage (1-3). These pulmonary complications often result in bronchiectasis, air trapping, hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and eventually cor pulmonale (1). The prevalence of CF among high-risk Iranian children has been estimated at approximately 1% (4).

Sleep is a vital physiological process that profoundly influences overall quality of life. Although sleep patterns evolve throughout the lifespan, the duration and quality of sleep depend on multiple factors, including age, gender, genetics, physical health, psychological status, and environmental conditions (2, 5). In children, sleep architecture is closely linked to growth and developmental stages (6).

Sleep disorders in pediatric populations encompass a range of conditions that disrupt normal sleep quantity, quality, or behaviors, and may include pathological events during sleep. These disturbances can lead to cognitive deficits, behavioral problems, impaired attention, academic difficulties, and reduced quality of life (7, 8).

Despite being among the most common behavioral issues in children, sleep disorders often remain underdiagnosed, particularly in Iran, where their prevalence in children aged 6 to 15 years ranges from 26.9% to 50.4% (9). The pathophysiological features of CF provide a strong rationale for anticipating a high burden of sleep disorders. We hypothesize that specific CF-related symptoms directly disrupt sleep architecture, leading to disturbances measurable by standard pediatric sleep tools. For example, frequent nocturnal cough and shortness of breath are likely to cause repeated "night wakings" and "sleep-disordered breathing." Nocturnal hypoxemia may not only contribute to sleep fragmentation but also lead to "parasomnias" (e.g., sleep terrors, confusional arousals) and "Daytime Sleepiness." Moreover, common comorbidities like gastroesophageal reflux can cause discomfort and pain, potentially manifesting as "Sleep Anxiety" and "Bedtime Resistance," while also contributing to "night wakings." Evidence supports this: Pulmonary dysfunction, impaired gas exchange, and cardiac complications in CF patients are known to contribute to disrupted sleep patterns (1, 10, 11).

Approximately 38% of children with CF experience sleep-related problems that negatively impact daily functioning and quality of life (8). A meta-analysis comparing children with CF to healthy peers reported reduced sleep efficiency and lower nocturnal oxygen saturation among the CF group (12). Furthermore, Meltzer et al. identified significant differences in sleep architecture and breathing-related sleep symptoms in children with CF compared to controls (8). Other research has documented increased nocturnal awakenings and decreased sleep efficiency in pediatric CF patients (13).

Despite the vital role of adequate sleep in the health of children with CF, research on sleep disorders in Iranian children and adolescents with CF is limited.

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate sleep disorders in Iranian children and adolescents with CF compared to healthy peers.

3. Methods

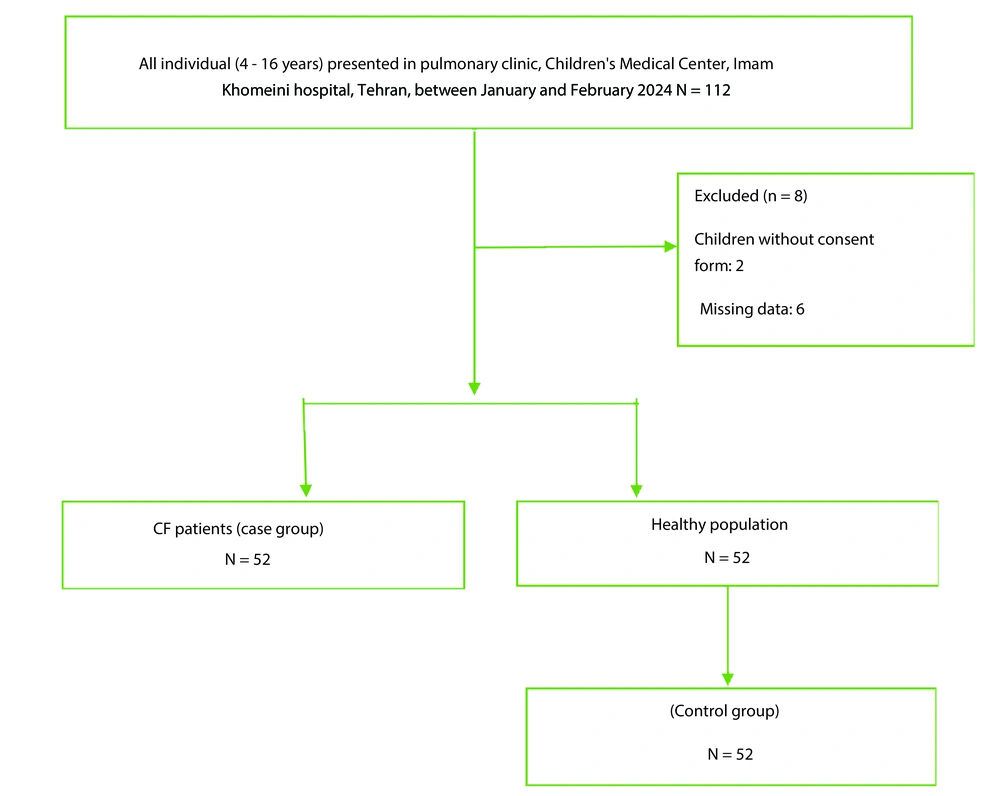

This case-control study was conducted in the pulmonary clinic, Children's Medical Center, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran. The cases were defined as all CF patients (4 - 16 years) who were diagnosed with CF using either a sweat test or genetic testing. The sample size in this study consisted of both the case and the control groups. Cases were defined as all CF patients (4 - 16 years) who referred to the Children's Medical Center hospital between January and February 2024. The control group included children who presented to the Children's Medical Center hospital without any confirmed disease, during the same period. A case-control design with a 1:1 ratio was employed. Consecutive eligible children with CF presenting to the clinic during the study period were invited to participate as cases. For each case, one control was randomly selected from a list of healthy children presenting for routine check-ups during the same period, using computer-generated random numbers (Figure 1).

3.1. Control Selection Process

The control group was recruited concurrently from the same tertiary care hospital to ensure derivation from a similar healthcare-seeking population and geographic catchment area as the case group, thereby mitigating potential selection bias related to healthcare access. Controls were identified from the general pediatric clinic during attendance for routine well-child examinations or for minor, resolved acute illnesses (e.g., uncomplicated upper respiratory infections). We employed a random sampling strategy using a computer-generated random number sequence to select participants from a daily roster of eligible children. To enhance the internal validity of the study and minimize confounding, we established the following exclusion criteria for controls: (1) A diagnosed chronic medical condition (e.g., asthma, diabetes); (2) any known neurological or cardiovascular disorder; or (3) current use of medication known to influence sleep architecture or daytime alertness (e.g., stimulants, sedating antihistamines, anticonvulsants). This approach was designed to create a control group representative of the underlying source population from which the cases arose, approximating the exposure distribution (i.e., sleep characteristics) had they not developed the condition under investigation.

Children whose parents were aware of their sleep habits were included in the study. Also, individuals with underlying diseases such as cardiovascular, neurological, or primary pulmonary hypertension in CF patients (case group), and any confirmed disease in healthy children (control group), were excluded.

The following covariates were selected a priori as possible confounders based on subject matter knowledge: Demographic data and participant characteristics including age, sex, educational status, age of diagnosis, and history of related disorders and anthropometric indices (weight and height).

3.2. Outcome Variables

Sleep disorders are common in children and adolescents and are influenced by sleep hygiene, circadian disruptions, medical conditions, and psychiatric disorders (14). This study used the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) to assess sleep disorders.

3.3. Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire

The CSHQ is a widely used parent-report screening tool for common childhood sleep problems, consisting of 45 retrospective items rated on a 3-point scale (usually, sometimes, rarely) that assess sleep behaviors over the past week. A total sleep disturbance score is calculated from 33 items spanning eight subscales: Bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness. The Persian version of the CSHQ has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in Iranian populations. Studies report good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients around 0.68 to 0.83 and strong test-retest reliability with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.82 to 0.91 across domains. Confirmatory factor analyses support the questionnaire’s construct validity. Sensitivity and specificity for detecting pediatric sleep disorders are approximately 0.80 and 0.72, respectively. The Persian CSHQ has been validated in the Iranian population, confirming its utility for clinical and research use in Iran (15-17).

In this study, parents were requested to remember and report on sleep patterns from the previous week. The items were evaluated using a 3-point scale: Usually (5 to 7 times per week), sometimes (2 to 4 times per week), and rarely (0 to 1 time per week). For the primary binary outcome, a total CSHQ score of > 41 was used to define the presence of a clinically significant sleep disorder, consistent with the validation study by Owens et al. (18).

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For both groups, children were included only if their parents or legal guardians were aware of their sleep habits and could complete the questionnaire. Additional exclusion criteria for the case group included the presence of comorbid conditions that could independently associate with severe sleep disruption, such as significant cardiovascular or neurological disease, or primary pulmonary hypertension. In the control group, any parent-reported confirmed chronic disease led to exclusion.

3.5. Data Collection

This study collected data using the CSHQ and a researcher-designed baseline checklist.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as N (%) and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Chi-square or Fisher's exact test assessed relationships between categorical variables, while the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test evaluated normality of continuous variables. Independent t-tests compared continuous variables between groups. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyzed the association between sleep disorders and CF in children and adolescents. Variables showing a P-value < 0.25 in univariable analysis were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression model. This liberal threshold is recommended to avoid excluding variables that may be important contributors in the multivariable context (19). In addition to this statistical screening, variables considered to be theoretically important confounders based on existing literature were assessed for inclusion in the multivariable model regardless of their statistical significance in univariable analysis (20). Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P-value < 0.05 for ORs with 95% CIs. Data analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

3.7. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Research Ethical Review of Iran University of Medical Sciences (approval number: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.160). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The researcher assured the participants that the information obtained would remain confidential. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 104 participants were initially assessed for inclusion in the study. Among them, 52 children with CF were in the case group, while 52 healthy children were selected as the control group. Approximately 50.4% of the participants were female. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) for age, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were 8.3 ± 3.8 years, 27.20 ± 12.2 kg, and 14.61 ± 5.3, respectively. As detailed in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, and height (P > 0.05). However, the mean BMI of children with CF was significantly lower compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05).

| Variables | Case Group (n = 52) | Control Group (n = 52) | Total (N = 104) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 8.64 ± 3.81 | 8.01 ± 3.91 | 8.32 ± 3.86 | 0.415 b |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 29 (55.8) | 30 (56.6) | 59 (56.2) | 0.902 c |

| Male | 23 (44.2) | 22(43.4) | 45(43.8) | |

| Height (cm) | 130.64 ± 59.12 | 132.29 ± 32.56 | 131.48 ± 46.16 | 0.256 c |

| Weight (kg) | 24.25 ± 10.58 | 28.16 ± 14.31 | 26.23 ± 12.62 | 0.070 c |

| BMI | 14.3 ± 6.1 | 16.1 ± 2.3 | 15.2 ± 4.3 | 0.034 c, d |

| Parents' education levels | ||||

| Diploma or lower | 28 (54.7) | 28 (52.8) | 56 (53.8) | 0.425 c |

| College degree | 15 (30.2) | 12 (21.8) | 27 (25.7) | 0.165 c |

| Upper graduated | 8 (15.1) | 13 (25.4) | 21 (21.0) | 0.091 c |

a Values are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b According to t-test.

c According to Pearson chi2.

d Statistically significant.

4.2. Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 2 presents the frequency of key clinical symptoms and comorbidities in children with CF compared to healthy controls. The results show that children with CF experience a significantly higher burden of clinical symptoms than the control group. High blood pressure was observed in 11.5% of the CF group, while none of the controls had this condition. Shortness of breath was reported in 22.4% of children with CF and was absent in the control group. Daytime and nighttime cough were also much more prevalent in the CF group (38.5% and 34.6%, respectively) compared to controls (3.8% and 1.9%). Gastrointestinal symptoms were common among children with CF, with 78.8% experiencing fatty diarrhea or requiring CREON enzyme supplementation, and 34.6% reporting gastroesophageal reflux. These symptoms were rare or absent in the control group. Upper airway complications such as sinusitis (9.6%) and nasal polyps (13.5%) were reported exclusively in the CF group.

| Variables | Case Group (CF, n = 52) | Control Group (n = 52) | Total (N = 104) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | 6 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (5.8) | < 0.05 |

| Shortness of breath | 12 (22.4) | 0 (0) | 12 (11.5) | < 0.001 |

| Daytime cough | 20 (38.5) | 2 (3.8) | 22 (21.2) | < 0.001 |

| Nighttime cough | 18 (34.6) | 1 (1.9) | 19 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Fatty diarrhea/CREON use | 41 (78.8) | 0 (0) | 41 (39.4) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 18 (34.6) | 2 (3.8) | 20 (19.2) | < 0.001 |

| Sinusitis | 5 (9.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.8) | 0.021 |

| Nasal polyps | 7 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.7) | 0.007 |

a Values are presented as No. (%).

4.3. Comparison of Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire Scores Between Study Groups

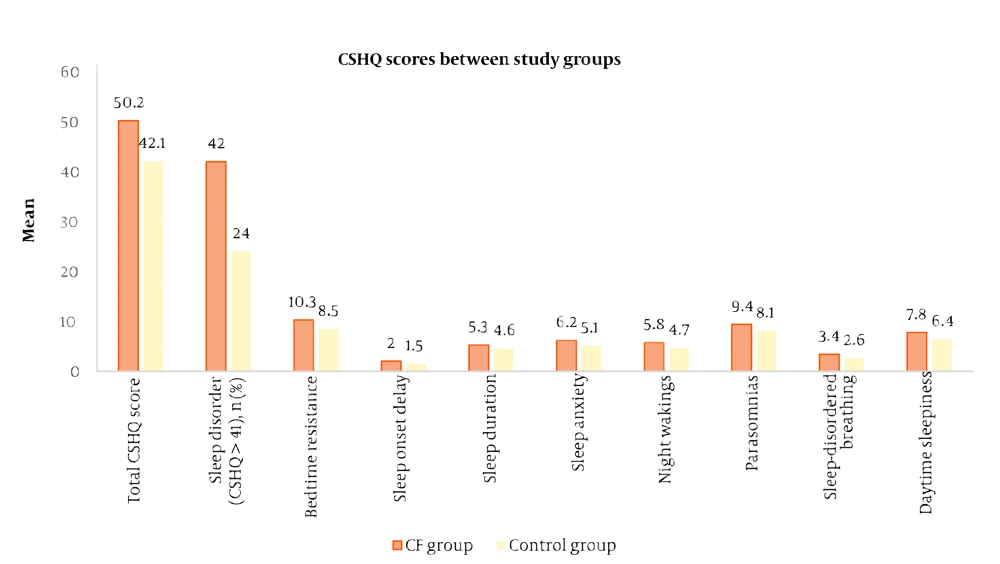

Table 3 compares CSHQ scores between the CF group and healthy controls. The mean total CSHQ score was significantly higher in the CF group (51.05 ± 5.20) compared to the control group (47.85 ± 5.05; P = 0.002), indicating a greater overall burden of sleep disturbances among children with CF. As detailed in Table 3, children with CF had significantly higher scores (indicating more problems) across all eight CSHQ subscales compared to healthy controls (all P-values < 0.05). The subscales with the most pronounced differences (P < 0.001) were bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, night wakings, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness.

| Sleep Disorder / CSHQ Subscale | CF Group (n = 52) | Control Group (n = 52) | Total (N = 104) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CSHQ score | 51.05 (5.20) | 47.85 (5.05) | 49.45 (5.12) | 0.002 |

| Sleep disorder (CSHQ > 41) | 42 (80.8) | 24 (46.2) | 66 (63.5) | < 0.001 |

| Bedtime resistance | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep onset delay | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.002 |

| Sleep duration | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Sleep anxiety | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Night wakings | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Parasomnias | 9.4 ± 1.9 | 8.1 ± 1.6 | 8.7 ± 1.9 | 0.001 |

| Sleep-disordered breathing | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 7.1 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: CSHQ, Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire; CF, cystic fibrosis.

a Values are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

Beyond the subscale scores, analysis of individual questionnaire items provided further detail on the nature of these sleep disturbances. A significantly higher proportion of children with CF struggled at bedtime (90% vs. 46%, P < 0.001), fell asleep in others’ beds (75% vs. 51%, P = 0.022), and reported a fear of sleeping in a dark room (75% vs. 51%, P = 0.012). Delayed sleep onset was also more frequent in the CF group (94% vs. 69%, P = 0.001), and more children with CF moved to someone else’s bed during the night (78% vs. 56%, P = 0.022).

Figure 2 compared the mean CSHQ total and subscale scores between children with CF and healthy controls. The figure shows that children with CF consistently have higher total CSHQ scores and higher scores across all subscales including bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration problems, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness, indicating a greater prevalence and severity of sleep disturbances in the CF group compared to controls.

4.4. Association Between Cystic Fibrosis and Sleep Disorders: Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios

Table 4 presents the crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between CF and the presence of sleep disorders, as well as for each of the CSHQ subscales. Children with CF had significantly higher odds of having a sleep disorder (CSHQ > 41) compared to healthy controls (crude OR: 5.18, 95% CI: 2.14 – 12.52; adjusted OR: 4.89, 95% CI: 1.95 – 12.27; P < 0.001). Similarly, the odds of exhibiting bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, night wakings, parasomnias, and daytime sleepiness were all significantly elevated in the CF group, both before and after adjustment for weight and BMI. Children with CF were nearly eight times more likely to experience sleep onset delay than controls (adjusted OR: 7.82, 95% CI: 1.99 – 30.68; P = 0.001), and more than twice as likely to have significant bedtime resistance (adjusted OR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.16 – 6.07; P = 0.022) or night wakings (adjusted OR: 2.75, 95% CI: 1.16 – 6.54; P = 0.022). The odds of parasomnias (adjusted OR: 2.68, 95% CI: 1.22 – 5.91; P = 0.012) and daytime sleepiness (adjusted OR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.02 – 4.88; P = 0.045) were also significantly increased among CF patients. No statistically significant associations were found for sleep duration, sleep anxiety, or sleep-disordered breathing after adjustment.

| Variables | CF | Control | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR b (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disorder (CSHQ > 41) | 42 (80.8) | 24 (46.2) | 5.18 (2.14 - 12.52) | 4.89 (1.95 - 12.27) | < 0.001 c |

| Bedtime resistance | 39 (75.0) | 27 (51.9) | 2.80 (1.25 - 6.28) | 2.65 (1.16 - 6.07) | 0.022 c |

| Sleep onset delay | 49 (94.2) | 36 (69.2) | 8.18 (2.11 - 31.65) | 7.82 (1.99 - 30.68) | 0.001 c |

| Sleep duration | 28 (53.8) | 18 (34.6) | 2.20 (1.01 - 4.80) | 2.12 (0.96 - 4.67) | 0.06 |

| Sleep anxiety | 27 (51.9) | 22 (42.3) | 1.48 (0.69 - 3.18) | 1.41 (0.65 - 3.04) | 0.36 |

| Night wakings | 41 (78.8) | 29 (55.8) | 2.89 (1.23 - 6.77) | 2.75 (1.16 - 6.54) | 0.022 c |

| Parasomnias | 35 (67.3) | 22 (42.3) | 2.80 (1.28 - 6.10) | 2.68 (1.22 - 5.91) | 0.012 c |

| Sleep-disordered breathing | 22 (42.3) | 13 (25.0) | 2.18 (0.96 - 4.93) | 2.05 (0.89 - 4.69) | 0.09 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 34 (65.4) | 23 (44.2) | 2.37 (1.09 - 5.17) | 2.23 (1.02 - 4.88) | 0.045 c |

Abbreviation: CSHQ, Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire.

a Values are presented as No. (%).

b Adjusted for weight and BMI.

c Statistically significant.

5. Discussion

This case-control study examined sleep disorder prevalence and characteristics in Iranian children and adolescents with CF versus the control group. Results showed that children with CF have significantly more sleep disturbances across various domains, measured by the Children’s CSHQ, than healthy controls. These findings align with prior research in other populations, highlighting the global importance of addressing sleep issues in pediatric CF patients.

5.1. Comparison with Other Studies

Results showed that children with CF have significantly more sleep disturbances (Total CSHQ score: 51.05 vs. 47.85, P = 0.002) across various domains, measured by the Children’s CSHQ, than healthy controls. Meltzer and Beck showed that children with CF had more frequent bedtime resistance, delayed sleep onset, and night wakings compared to healthy controls, which closely mirrors our results. Their study also highlighted the impact of respiratory symptoms and disease management routines on sleep quality, factors that were prominent in our cohort as well (8).

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Reiter et al. further substantiates our findings, demonstrating that children with CF have significantly reduced sleep efficiency, increased nocturnal awakenings, and lower nocturnal oxygen saturation compared to healthy peers. The meta-analysis included studies from diverse geographic regions, suggesting that sleep disturbances are a universal concern in pediatric CF, regardless of cultural or healthcare system differences (12).

Ramos et al. specifically investigated nocturnal hypoxemia in children and adolescents with CF, reporting that oxygen desaturation during sleep was common and associated with increased sleep fragmentation and daytime sleepiness. Our study similarly found elevated rates of night wakings and daytime sleepiness in the CF group, reinforcing the link between respiratory compromise and sleep disruption (10).

Amin et al. examined the relationship between pulmonary function and sleep disturbance in stable pediatric CF patients, finding that even in the absence of acute exacerbations, children with CF had more sleep-related complaints and lower sleep quality than their healthy counterparts (13). This supports our observation that sleep problems in CF are not solely attributable to acute illness but may be chronic and persistent.

Shakkottai et al. provided a comprehensive review of sleep disturbances in pediatric CF, identifying a range of contributing factors including chronic cough, airway obstruction, and the psychological burden of chronic disease management (1). The review emphasized that sleep disorders in CF are multifactorial and may be exacerbated by comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux and sinus disease, both of which were more prevalent in our CF cohort.

Our findings are also consistent with studies conducted in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries. Amizadeh et al. reported a high baseline prevalence of sleep disturbances among Iranian children, but our data indicate that CF further amplifies this risk (9). The use of the validated Persian version of the CSHQ in our study, as established by Fallahzadeh et al. and Asgarian et al., strengthens the reliability and comparability of our results within the Iranian context (15, 16).

Furthermore, Byars et al. highlighted the bidirectional impact of sleep disturbances on both children with CF and their caregivers, suggesting that sleep problems can affect family functioning and overall quality of life (11). This underscores the broader implications of our findings, as sleep health in CF should be addressed not only for the patient but also for the family unit.

Despite some variations in methodology and sample characteristics, the convergence of evidence across studies supports the conclusion that sleep disturbances are a significant and under-recognized comorbidity in pediatric CF. Our study adds to this literature by providing data from an Iranian population, where research on this topic has been limited.

5.2. Causal Interpretation of Findings

The study reveals a strong, independent association between CF and sleep disturbances. However, causal inference is limited by the case-control design, which precludes assessment of temporality. A unidirectional causal path from CF to sleep disruption is biologically plausible. Nocturnal hypoxemia, cough, pain, and systemic inflammation may directly contribute to sleep architecture fragmentation. Conversely, a bidirectional model is highly probable: Sleep deprivation can worsen daytime symptom perception, impair pulmonary clearance, and potentiate inflammatory pathways, thereby increasing disease burden.

Residual confounding presents a key limitation. Unmeasured or imprecisely quantified factors including objective disease severity (e.g., FEV1% decline), treatment complexity, socioeconomic status, and psychological comorbidities may partly explain the observed association.

5.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study has several strengths, including a robust case-control design that facilitates a direct comparison between children with CF and healthy peers from the same community. The use of the validated Persian version of the CSHQ ensures a culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment of sleep disturbances. Furthermore, we enhanced internal validity by excluding participants with other chronic conditions and by adjusting for key potential confounders such as weight and BMI in our analyses.

However, the findings must be interpreted in the context of certain limitations. The sample size, while sufficient to detect statistically significant group differences, was relatively small and recruited from a single tertiary referral center in Tehran. This design limits the generalizability of our prevalence estimates, as our cohort may not be fully representative of the broader, more heterogeneous population of Iranian children with CF, particularly those managed in primary or secondary care settings or in other geographic regions. The single-center design also means that center-specific practices could influence results.

Additionally, as with any observational study, residual confounding is possible. We lacked data on other potential confounders such as psychological and environmental contributors, socioeconomic status, detailed medication regimens (e.g., corticosteroids), specific pulmonary function measures, and environmental sleep factors (e.g., bedroom sharing), which could influence sleep habits.

Despite these limitations, this study provides crucial initial evidence and establishes a baseline for understanding the spectrum of sleep disturbances in Iranian children with CF. The large and consistent effect sizes observed across multiple sleep domains strongly suggest that sleep problems are a clinically significant comorbidity in this population, warranting further investigation.

5.4. Conclusions

This case-control study demonstrates that Iranian children and adolescents with CF exhibit a substantially higher prevalence, severity, and odds of parent-reported sleep disturbances compared to healthy peers from the same clinical setting. The robust association, which persisted after adjustment for key confounders, underscores sleep disruption as a significant comorbid condition in pediatric CF. These findings highlight an imperative for clinicians to integrate routine sleep screening into standard CF care. Proactive assessment and management of sleep problems may improve quality of life and daily functioning. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are necessary to determine the directionality of this association, clarify underlying mechanisms, and evaluate whether improving sleep can positively influence clinical outcomes in CF.