1. Background

Bronchiolitis is an acute viral infection of the lower respiratory tract and represents one of the most common causes of hospitalization among infants and young children under two years of age, particularly during the winter season. The disease typically begins with upper respiratory symptoms such as nasal congestion and rhinorrhea, which may progress to wheezing, cough, and feeding difficulties. In severe cases, it can lead to respiratory distress, hypoxemia, and dehydration requiring hospitalization (1-4). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the predominant etiologic agent, although other respiratory viruses may also cause bronchiolitis. Globally, bronchiolitis accounts for an estimated 33 million cases and approximately 3.6 million hospitalizations annually, resulting in up to 118,000 infant deaths — most occurring in low- and middle-income countries (5, 6). Disease severity is commonly assessed using clinical scoring systems such as the Modified Tal Score and the Acute Bronchiolitis Severity Score, which guide management decisions and predict the need for intensive care (7, 8). The wide spectrum of disease severity is influenced by factors including age, immune status, viral strain, and comorbidities (9). Early recognition of high-risk patients is therefore essential. Increasing evidence suggests that coagulation biomarkers — particularly D-dimer — may serve as valuable prognostic indicators, reflecting hypercoagulability and thrombotic activity in severe respiratory diseases (10, 11). Clinically, a D-dimer cutoff value of 200 ng/mL is considered, and any deviations from this level may be regarded as abnormal (12). Previous studies have reported significant associations between elevated serum D-dimer levels and disease severity or poor prognosis in several respiratory and cardiopulmonary disorders. For instance, in interstitial lung disease, higher D-dimer levels were linked to an increased risk of acute exacerbation, hospitalization, and mortality (13). Similarly, systematic reviews have demonstrated the diagnostic and prognostic value of D-dimer, along with cardiac troponins and NT-proBNP, across acute cardiopulmonary syndromes such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, heart failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, and interstitial lung disease (14). Further studies in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) have shown that D-dimer levels rise with increasing disease severity and are higher among patients with comorbidities, suggesting its role as a reliable biomarker for assessing CAP severity (15). Likewise, research in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has revealed that elevated D-dimer levels are independent predictors of in-hospital and one-year mortality, correlating with higher inflammatory burden and poorer respiratory function (16, 17). Collectively, these findings support D-dimer as a robust biomarker of disease severity and adverse outcomes in adult respiratory and cardiopulmonary disorders. However, no previous studies have specifically evaluated the relationship between D-dimer levels and bronchiolitis severity in children.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to investigate the association between serum D-dimer levels and disease severity in pediatric bronchiolitis.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a retrospective observational analytical cohort study conducted at Ali-Asghar Children’s Hospital over a one-and-a-half-year period. The initial sampling frame comprised 348 medical records of infants and children hospitalized with a confirmed diagnosis of bronchiolitis during this period. Certain criteria (Table 1) were applied to ensure that only records with complete and relevant clinical data were eligible for analysis. From the eligible records, 102 cases were selected through simple random sampling using STATA. The sample size of 102 patients was determined based on the statistician’s recommended formula to ensure sufficient statistical power. Only records with complete clinical data were included, ensuring that the selected cohort was representative of the overall hospitalized bronchiolitis population. This approach enhanced the validity and generalizability of the analyses. All patients in the study were evaluated for COVID-19 infection as well as cardiac function.

| Criteria Type | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | Age < 3 years; confirmed bronchiolitis diagnosis (clinical + paraclinical); at least one serum D-dimer measurement during hospitalization |

| Exclusion | Incomplete or illegible medical records; congenital or acquired heart disorders; primary or secondary immunodeficiencies; history of pulmonary embolism; COVID-19 infection during study period; History of surgery during hospitalization; active trauma; ongoing anticoagulant therapy or coagulation disorders (DVT, thrombosis, DIC); premature infants |

3.2. Diagnosis and Assessment of Bronchiolitis Severity

Bronchiolitis diagnosis and severity were determined according to established clinical criteria using the Global Respiratory Severity Score (GRSS) (18). This scoring system evaluates disease severity based on clinical signs such as tachypnea, cough, wheezing, dyspnea, fever, and oxygen saturation. By assigning a quantitative severity score, clinicians can objectively evaluate the disease and guide appropriate therapeutic decisions (Table 2) (19).

| Parameters | Scoring Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mo) | Younger infants receive higher scores | Adjusted for exact age due to increased sensitivity in younger infants |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | ≥ 95% = 0; 90 - 94% = 1; < 90% = 2 | Lower oxygen saturation corresponds to higher severity |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | Age-specific range scoring | Higher respiratory rates receive higher scores |

| General appearance | Normal = 0; mild–moderate illness = 1; severe = 2 | Based on overall patient condition and distress |

| Wheezing | None = 0; mild = 1; moderate = 2; severe = 3 | Assesses the intensity of wheezing sounds |

| Rales/rhonchi | None = 0; mild–moderate = 1; severe = 2 | Evaluates presence of abnormal lung sounds |

| Intercostal retractions | Absent = 0; present = 1 | Indicates additional respiratory effort |

| Cyanosis | Absent = 0; present = 2 | Assesses bluish discoloration of skin or lips |

| Lethargy | Absent = 0; present = 1 | Indicates reduced responsiveness or drowsiness |

| Air movement | Normal = 0; decreased = 1 | Reflects airway obstruction or poor airflow |

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To minimize confounding factors and improve the accuracy and reliability of study results, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (Table 1).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were summarized as means ± standard deviations for normally distributed data or medians with interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Normality was assessed using histograms, Q-Q and P-P plots, skewness, kurtosis, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Group comparisons were conducted using t-tests for continuous variables. Associations between risk factors and outcomes were evaluated using scatter plots and both linear and logistic regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18, with a significance level of P < 0.05 (20).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Findings

All patients included in the study underwent COVID-19 testing, and all results were negative. Additionally, cardiac function was assessed through measurement of enzymes, including pro-BNP and troponin; all patients demonstrated normal levels, with no evidence of cardiac enzyme elevation. The results indicated that 67.6% of the participants were boys and 32.4% were girls, demonstrating a predominance of male participants in the study sample. The mean age of the children was 160.68 days, with a relatively high standard deviation (188.6 days), suggesting considerable variability in age among the study population (Table 3).

| Variables and Category | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 69 (67.6) |

| Female | 33 (32.4) |

| General condition | |

| Good | 88 (86.3) |

| Mild/moderate | 11 (10.8) |

| Severe | 3 (2.9) |

| Wheezing | |

| None | 54 (52.9) |

| Mild | 33 (32.4) |

| Severe | 15 (14.7) |

| Rales | |

| None | 69 (67.6) |

| Mild | 16 (15.7) |

| Severe | 17 (16.7) |

| Retraction | |

| None | 75 (73.5) |

| Present | 27 (26.5) |

| Cyanosis | |

| None | 98 (96.1) |

| Present | 3 (2.9) |

| Lethargy | |

| None | 99 (97.1) |

| Present | 2 (2.0) |

| Air movement | |

| Normal | 98 (96.1) |

| Reduced | 4 (3.9) |

| Respiratory distress | |

| None | 44 (43.1) |

| Present | 58 (56.9) |

| Tachypnea | |

| None | 74 (72.5) |

| Present | 28 (27.5) |

| Poor Feeding | |

| None | 53 (52.0) |

| Present | 49 (48.0) |

| PICU admission | |

| No | 86 (84.3) |

| Yes | 16 (15.7) |

| Mortality | |

| No | 102 (100) |

Abbreviation: PICU, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

4.2. Analytical Findings

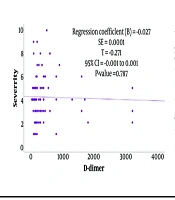

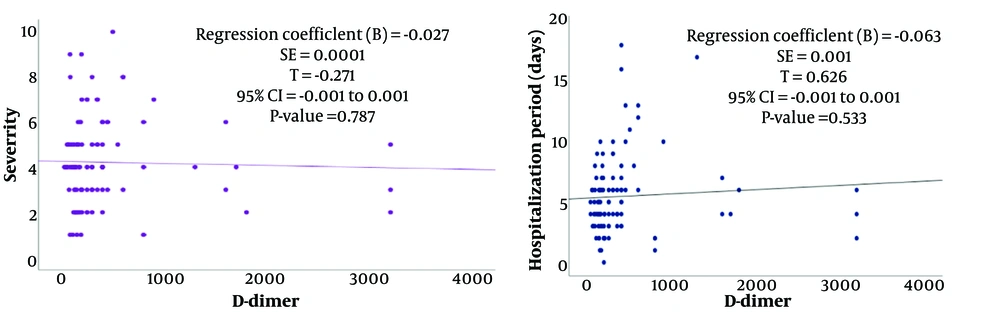

Notably, no mortality was reported among the study participants. The investigation revealed a very weak correlation between serum D-dimer levels and the clinical severity of bronchiolitis in children, which was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Similarly, a weak positive correlation was observed between serum D-dimer levels and the length of hospital stay, but this association also lacked statistical significance (P > 0.05) (Figure 1). Logistic regression analysis further evaluated the relationship between serum D-dimer levels and the need for PICU admission, and no statistically significant association was found (P = 0.480).

5. Discussion

Although the relationship between D-dimer and certain pediatric conditions, such as COPD and asthma (17, 21), has been studied, a relationship between this protein and bronchiolitis has not been established. In this retrospective study of pediatric bronchiolitis, we found no significant correlation between serum D-dimer levels and clinical severity, length of stay, or PICU admission. This contrasts with findings in other respiratory syndromes. For example, in CAP, higher D-dimer levels have been consistently linked to more severe illness and higher pneumonia severity index scores (15). Similarly, studies in children with severe COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome report that elevated D-dimer predicts intensive care unit (ICU) care and mortality (22). In a large pediatric PICU cohort, non-survivors had markedly higher D-dimer (5.22 vs. 1.68 mg/L) than survivors, and D-dimer remained an independent predictor of mortality after adjustment (23). These data suggest that in systemic or severe inflammatory states, D-dimer reflects extensive coagulopathy and disease burden. By contrast, acute viral bronchiolitis in otherwise healthy infants is often a self-limited airway disease. Our findings imply that D-dimer is not elevated proportionately in routine bronchiolitis and thus lacks utility for risk stratification. Unlike pneumonia or COVID-19, RSV and other bronchiolitis viruses primarily cause small-airway inflammation without the pronounced endothelial injury or thrombosis that drives fibrin degradation (24). It is plausible that the hemostatic activation in most bronchiolitis cases is too mild to generate a clear D-dimer signal. In this cohort, even patients requiring hospitalization had a generally benign course (no deaths recorded), limiting the spectrum of severity. Therefore, the lack of association may reflect the relatively moderate clinical courses and small sample size rather than a definitive absence of any role.

5.1. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the data were extracted from medical records that were not originally collected for research purposes, which may have affected the accuracy and completeness of the information. Second, the extended study period introduces the possibility of reporting errors or missing data, particularly in older records. Third, and most critically, this was a single-center study conducted at Ali-Asghar Children’s Hospital. As a result, the patient population may not fully represent the broader regional or national population, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Differences in demographic characteristics, clinical practices, and healthcare access across other settings may influence the applicability of these results. Therefore, caution is warranted when extrapolating our findings to populations beyond the study site, and multi-center studies are recommended to validate and extend these observations.

5.2. Recommendations for Future Research

It is recommended that future studies employ a prospective design to ensure more accurate and high-quality data collection and minimize potential recording errors. Expanding the study population to include both inpatient and outpatient cases could provide a more comprehensive representation of the full clinical spectrum of bronchiolitis and improve the generalizability of results. Increasing the sample size and conducting multi-center studies would enhance statistical power and reduce bias. Additionally, simultaneous evaluation of other inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers alongside D-dimer could offer a clearer understanding of disease pathophysiology. Detailed documentation of treatment variables, medications, and complications, as well as examining their impact on key clinical outcomes such as mortality and PICU admission, is also essential. Long-term follow-up studies on larger samples are recommended.

5.3. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the association between serum D-dimer levels and the severity of bronchiolitis in hospitalized children. The findings revealed a weak and statistically insignificant correlation between serum D-dimer levels and the clinical severity of bronchiolitis. Similarly, although a positive relationship was observed between D-dimer levels and the duration of hospitalization, this association was not statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis showed that D-dimer levels had no significant correlation with the need for admission to the PICU. Consistent with these results, the mean D-dimer level did not differ significantly between children admitted to the PICU and other patients. Overall, this study suggests that serum D-dimer levels are not a strong predictor of disease severity, length of hospital stay, or the need for intensive care in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis.