1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis, a neglected tropical disease, represents a major global public health challenge affecting nearly 100 countries worldwide, with an estimated annual incidence of 700,000 to 1 million new cases (1, 2). This vector-borne disease exhibits disproportionate prevalence in resource-limited regions with inadequate healthcare infrastructure, particularly in parts of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Eastern Mediterranean basin (3, 4). Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania, which are transmitted to humans via the bites of infected female phlebotomine sand flies (5). The disease manifests in various clinical forms, including cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), visceral leishmaniasis, and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Cutaneous leishmaniasis represents the most prevalent clinical form of the disease, characterized by debilitating and disfiguring skin lesions (6).

Conventional pharmacotherapeutic agents employed for leishmaniasis management, including antimonials, amphotericin B, miltefosine, and paromomycin, have exhibited diverse efficacy profiles (7). Nevertheless, concerns surrounding drug resistance, extended treatment protocols, and adverse events have undermined the clinical viability of these conventional agents (8, 9). Furthermore, the elevated costs and restricted accessibility of these drugs in endemic regions have amplified the healthcare disparities. Consequently, the suboptimal efficacy, high expenditure, and toxicity associated with current leishmaniasis pharmacotherapies have motivated the exploration of alternative treatment modalities (10). In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in the utilization of natural products, particularly essential oils derived from medicinal plants, as potential sources of novel anti-leishmanial agents (11).

Zataria multiflora and Thymus vulgaris are two aromatic plant species that have been extensively recognized for their diverse medicinal attributes and have been traditionally employed in folk medicine for the treatment of various ailments (12-14). Zataria multiflora and T. vulgaris have been widely used not only in traditional medicine but also as culinary herbs, underscoring their safety profile and low toxicity in human consumption. This dietary use supports their potential as biocompatible alternatives to synthetic drugs, which often exhibit severe side effects (15).

Preliminary studies have provided evidence for the anti-leishmanial potential of these plants. For instance, a hydroalcoholic extract of T. vulgaris has been shown to be significantly more effective than systemic glucantime in reducing ulcer size in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice (16). Furthermore, thymol and carvacrol, the principal bioactive components of these plants, have demonstrated direct activity against Leishmania parasites, with synthesized derivatives showing high potency and promising Selectivity Indices (SIs) (17). More recently, green-synthesized silver nanoparticles using T. vulgaris extract exhibited significant anti-leishmanial activity against both promastigote and amastigote forms of L. major (18).

Zataria multiflora, commonly referred to as Avishan-e-Shirazi or Shirazi thyme, is indigenous to Iran and other regions of the Middle East. This plant is known to be rich in essential oils and has been extensively documented to exhibit antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties (19, 20). Thymus vulgaris, commonly referred to as common thyme, is widely distributed throughout Europe and the Mediterranean region, and has been utilized in traditional medicinal practices for centuries (21).

The chemical composition of essential oils extracted from Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris has been extensively investigated, unveiling the presence of a diverse array of bioactive compounds, including monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and phenolic compounds (22, 23). These compounds are renowned for their wide-ranging biological activities, encompassing antimicrobial and antiparasitic properties (24). While previous studies have primarily focused on crude extracts of these plants or their use in synthesizing nanoparticles, our study targets their essential oils directly, which are more concentrated in bioactive compounds due to their hydrophobic nature and distillation-based extraction. Essential oils typically exhibit higher potency against pathogens compared to extracts, as they contain volatile terpenoids and phenolics that directly interfere with microbial membranes (25, 26).

2. Objectives

Given the limited and indirect data on the anti-leishmanial activity of the essential oils themselves (particularly from Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris) and their advantage of being natural, low-toxicity agents, this study aims to: Analyze the chemical composition of their essential oils, evaluate their efficacy against L. major, highlight their potential as safer therapeutic candidates for CL, addressing the unmet need for non-toxic treatments.

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Materials

The aerial parts of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris were collected in May 2023 from the mountainous regions surrounding Darab city in Fars Province, Iran. Plant identification was conducted by Dr. Moein, a specialist in pharmacognosy at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Voucher specimens of Z. multiflora (PM-1431) and T. vulgaris (PM-1430) were deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Pharmacognosy, School of Pharmacy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

3.2. Preparation and Extraction of Essential Oils

The essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris were extracted by hydrodistillation of the leaves using an all-glass Clevenger-type apparatus for a duration of 4 hours (27). The resulting essential oils were dehydrated using sodium sulfate and stored in a dark environment at 4°C until further analysis.

3.3. Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis was performed using a Hewlett-Packard 6890/5973 instrument operating at an ionization energy of 70.1 eV. The system was equipped with an HP-5 capillary column (phenyl methyl siloxane, 25 m × 0.25 mm i.d.), and helium (He) was employed as the carrier gas with a split ratio of 1:20. The oven temperature program included a three-minute hold at 60 °C, followed by a ramp to 260 °C for the detector. The carrier gas flow rate was set to 0.9 mL/min. To calculate the retention indices (RIs), the retention times of n-alkanes injected under the same chromatographic conditions were utilized. The identification of oil components was achieved by comparing the mass spectra and RIs with those reported in the literature, as well as by comparing the mass spectra with the Wiley library or published mass spectral data (28).

3.4. Identifying the Constituents of Essential Oils

The identification of the essential oil components was accomplished by comparing their respective retention times and mass spectra with those of known standards, the data from the Wiley 2001 library of the GC/MS system, as well as the information provided in the literature (29).

3.5. The Dilutions Preparation

Various dilutions of the essential oils were prepared following the methodology described by Saedi Dezaki et al (12). Specifically, 2 µL of the essential oil was dissolved in 988 µL of normal saline. To facilitate the dispersion of the essential oil within the normal saline, an additional 10 µL of Tween 20 was added to the experimental tube. The final solution was thoroughly mixed using a magnetic stirrer. The essential oils underwent a series of dilutions to achieve concentrations of 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL. The dilutions of the essential oils were chosen based on preliminary tests, which also confirmed that the combination of normal saline and Tween 20 did not affect parasite growth (12).

3.6. Parasite Preparation and Cell Culture

The promastigote form of the L. major parasite from the standard strain (MRHO/IR/75/ER) was utilized in this study. The parasite strain was obtained from the Department of Parasitology and Medical Mycology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. For the cultivation of parasite promastigotes, RPMI 1640 medium was supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 IU/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. The incubation temperature was maintained at 25°C. Mouse macrophage cells (J774) were obtained from the Central Laboratory at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, and employed for cell culture. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 IU/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. The incubation conditions for the cell culture were set at 37°C and 5% CO2.

3.7. Anti-leishmanial Effects Were Assessed Using Flow Cytometry

To evaluate the effects of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris essential oils on L. major promastigotes, a flow cytometry method was employed. Initially, 2 µL of the essential oils under investigation were dissolved in 10 µL of Tween 20 and subsequently diluted to a final volume of 1 ml with normal saline to create a stock solution. Serial dilutions were then prepared in normal saline to achieve the final testing concentrations. Subsequently, promastigotes in the logarithmic phase were assessed for evaluation. Initially, 2 × 10⁵ promastigotes were added to 12 Eppendorf tubes. Subsequently, six tubes received concentrations of Z. multiflora essential oil ranging from 31.25 to 1000 µg/mL, while the other six tubes were supplemented with concentrations of T. vulgaris essential oil in the same range.

The positive control (PC) tube contained 20 µg/mL of amphotericin B, while the negative control (NC) tube contained 1% Tween 20. After 2 hours of incubation at 25°C, all tubes were stained with 10 µL of propidium iodide (PI) at a final concentration of 50 µg/mL for 5 minutes in the dark. Flow cytometry was then performed using a BD Calibur flow cytometer. For each sample, 10,000 to 30,000 events were acquired. Cell populations were first gated based on forward and side scatter characteristics to exclude debris. Viability was assessed based on PI fluorescence intensity; the population of PI-negative events (viable cells) was quantified against PI-positive events (non-viable cells). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated using statistical analysis (12, 30).

3.8. Investigation of Anti-amastigote Effects

To measure the anti-amastigote effects of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris essential oils, experiments were performed in triplicate. For each replicate, 1 cm² cover slips were placed inside each of the wells of a 6-well microplate. Mouse macrophage cells were then seeded at a density of 3 × 10⁵ cells/ml and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Stationary phase promastigotes were subsequently added to the wells at a parasite to macrophage ratio of 6:1 (18 × 10⁵/ml) and incubated for an additional 6 hours under the same conditions. Free promastigotes were removed by washing with RPMI-1640 medium, and the parasite-infected macrophages were treated with different concentrations of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris essential oils (31.25 - 1000 μg/mL) for 24 and 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Amphotericin B at a concentration of 20 μg/mL was used as a PC. After the treatment, the slides were washed, dried, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa. The stained slides were then examined under a light microscope at 1000X magnification. For each experimental condition, at least 100 macrophages were randomly counted, and the percentage of infected macrophages as well as the mean number of amastigotes per macrophage were determined.

3.9. Cytotoxic Effects on Cellular Viability

The effects of essential oils from Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris on J774 macrophages were investigated following exposure to various concentrations of the essential oils (31.25 - 1000 µg/mL). These experiments were conducted in triplicate. For each replicate, cell culture plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 48 hours. Subsequently, cell viability was assessed using the MTT colorimetric assay, and the number of viable cells treated with various concentrations of the essential oils was compared to both the positive and NC groups.

3.10. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27) and GraphPad Prism (Version 10). The half-maximal IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of dose-response curves using GraphPad Prism. For the comparison of multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used. A P-value threshold of less than 0.05 was established to indicate statistical significance.

4. Results

4.1. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of the Essential Oils from Thymus vulgaris and Zataria multiflora

The extraction yielded 33 grams of essential oil (1.22%) from 2.7 kilograms of T. vulgaris and 43 grams of essential oil (2.86%) from 1.5 kilograms of Z. multiflora. The results of the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of the essential oils from T. vulgaris and Z. multiflora are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. A total of 16 compounds were identified in T. vulgaris, constituting 99.98% of the essential oils, while 14 compounds were identified in Z. multiflora, accounting for 100% of the analyzed essential oils. The main compounds identified in T. vulgaris included thymol (49.83%), γ-terpinene (14.93%), and cymene (10.99%), whereas the primary constituents of Z. multiflora were thymol (46.46%) and carvacrol (32.47%).

| No. | Type of compound | KI | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-thujene | 928 | 0.90 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 936 | 1.02 |

| 3 | Octen-3-ol | 980 | 1.12 |

| 4 | Myrcene | 993 | 1.33 |

| 5 | α-terpinene | 1021 | 2.81 |

| 6 | Cymene | 1033 | 10.99 |

| 7 | 1,8-Cineole | 1037 | 0.65 |

| 8 | γ-terpinene | 1069 | 14.93 |

| 9 | Linalool <tetrahydro-> | 1103 | 2.98 |

| 10 | Terpinene-4-ol | 1181 | 2.87 |

| 11 | Thymol methyl ether | 1238 | 1.96 |

| 12 | Carvacrol methyl ether | 1247 | 1.12 |

| 13 | Thymol | 1292 | 49.83 |

| 14 | Carvacrol | 1304 | 2.42 |

| 15 | Caryophyllene <(E-)> | 1425 | 4.31 |

| 16 | δ-cadinene | 1530 | 0.74 |

| 17 | Total | 99.98 |

Abbreviation: KI, Kovats Index.

| No. | Type of compound | KI | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-pinene | 937 | 1.77 |

| 2 | Myrcene | 993 | 0.85 |

| 3 | α-terpinene | 1020 | 1 |

| 4 | o-cymene | 1031 | 5.62 |

| 5 | γ-terpinene | 1064 | 3.58 |

| 6 | Linalool oxide | 1075 | 0.48 |

| 7 | Terpinene-4-ol | 1185 | 0.72 |

| 8 | Carvacrol methyl ether | 1249 | 1.51 |

| 9 | Thymol | 1289 | 46.46 |

| 10 | Carvacrol | 1295 | 32.47 |

| 11 | Caryophyllene <-E> | 1423 | 3.54 |

| 12 | Aromadendrene | 1447 | 0.51 |

| 13 | Bicyclogermacrene | 1505 | 0.85 |

| 14 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1588 | 0.64 |

| 15 | Total | 100 |

Abbreviation: KI, Kovats Index.

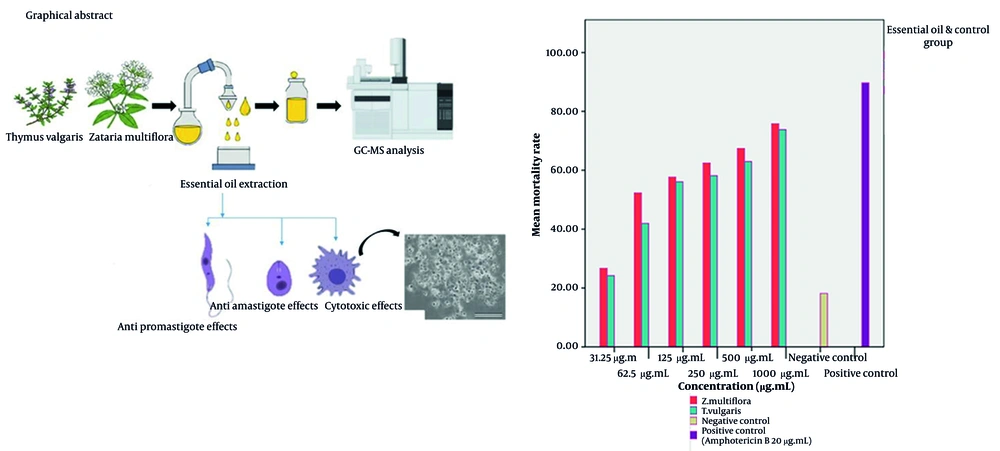

4.2. The Effect of Zataria multiflora and Thymus vulgaris Essential Oils on the Growth of Leishmania Major Promastigotes

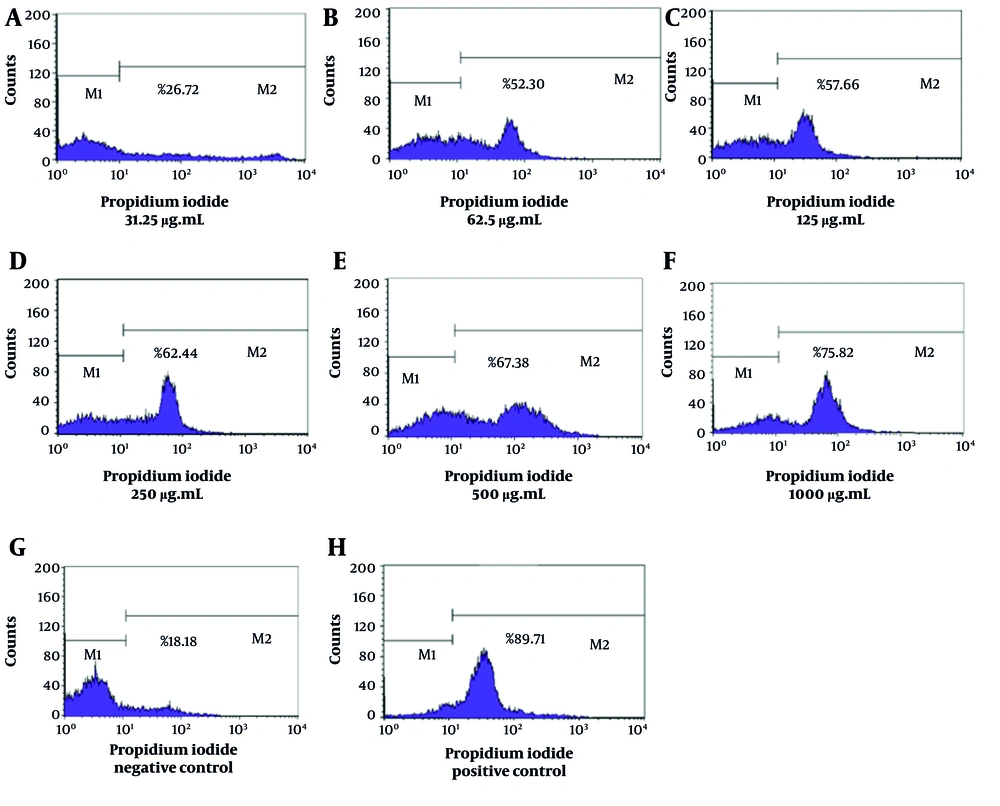

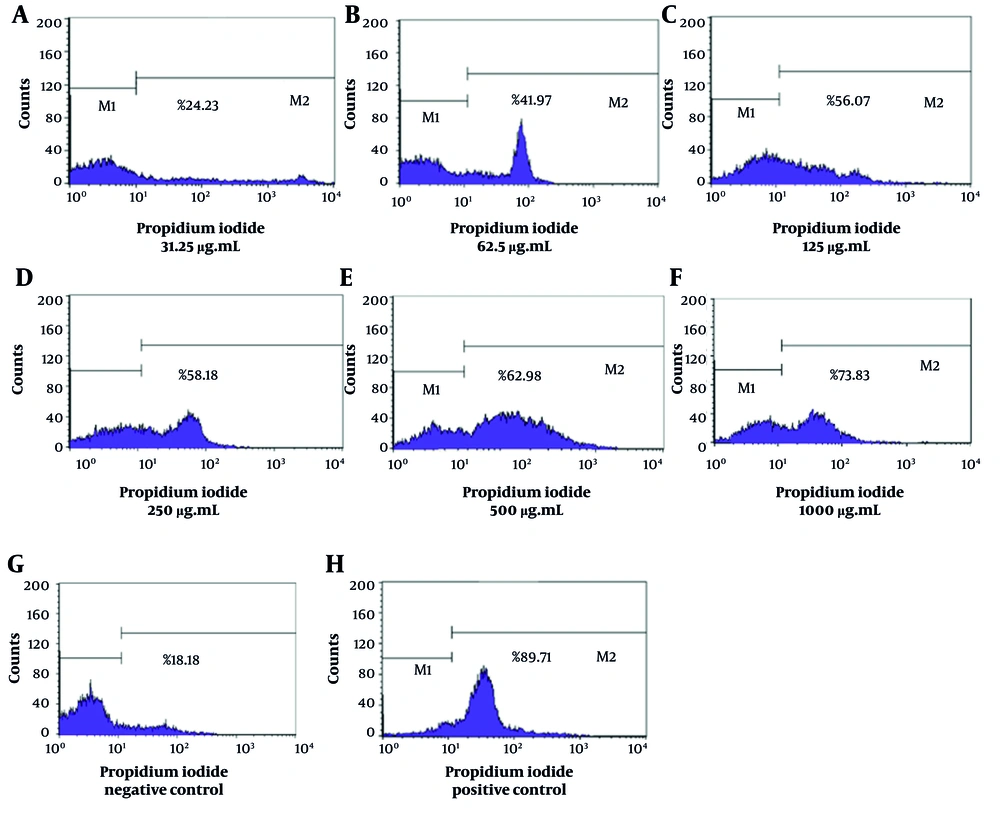

The flow cytometry analysis demonstrated significant variations in the mortality rates of L. major promastigotes when subjected to different concentrations of essential oils derived from T. vulgaris and Z. multiflora. The NC, consisting of Tween 20 and normal saline, exhibited a mortality rate of 18.18%, suggesting that promastigote mortality remained relatively low when no leishmanicidal agents were present. In contrast, the PC exhibited a significant mortality rate of 89.71%, which confirms the efficacy and sensitivity of L. major promastigotes to amphotericin B (Figure 1). The IC50 values for T. vulgaris and Z. multiflora were determined to be 92.75 µg/mL and 59.69 µg/mL, respectively.

The lethality rates of L. major promastigotes exposed to concentrations of Z. multiflora essential oil (31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 µg/mL) were found to be 26.72%, 52.3%, 57.66%, 62.44%, 67.38%, and 75.82%, respectively (Figure 2). Additionally, the lethality rates corresponding to the specified concentrations of T. vulgaris were 24.23%, 41.97%, 56.07%, 58.18%, 62.98%, and 73.83%, respectively (Figure 3). Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test) confirmed both essential oils significantly increased promastigote mortality compared to the NC (P < 0.05). The anti-promastigote activity of Z. multiflora essential oil was statistically superior to that of T. vulgaris. However, the efficacy of both essential oils was significantly lower than that of amphotericin B (PC) (P < 0.05).

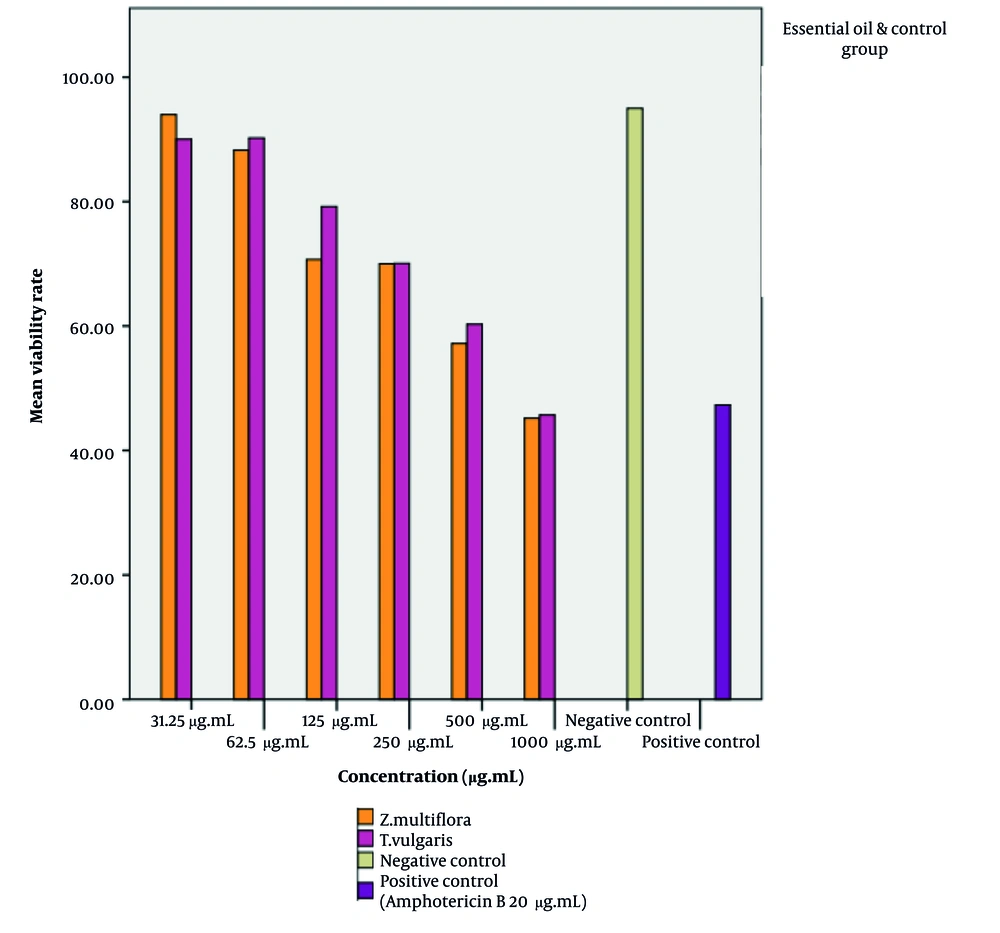

4.3. The Cytotoxicity of Zataria multiflora and Thymus vulgaris Essential Oils on J774 Macrophage Cells Was Evaluated Using the MTT Assay

The cytotoxic effects of the essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris on J774 macrophages were assessed after treatment with varying concentrations of the essential oils (31.25 - 1000 µg/mL) in 96-well microplates under conditions of 37°C, 5% CO₂, and 48 hours of incubation. Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay, and the results were expressed as the percentage of dead cells relative to those treated with amphotericin B and untreated macrophages (Figure 4). The CC50 values for T. vulgaris and Z. multiflora were determined to be 820.4 µg/mL and 799.6 µg/mL, respectively. Cell viability after exposure to amphotericin B was found to be 47.30%.

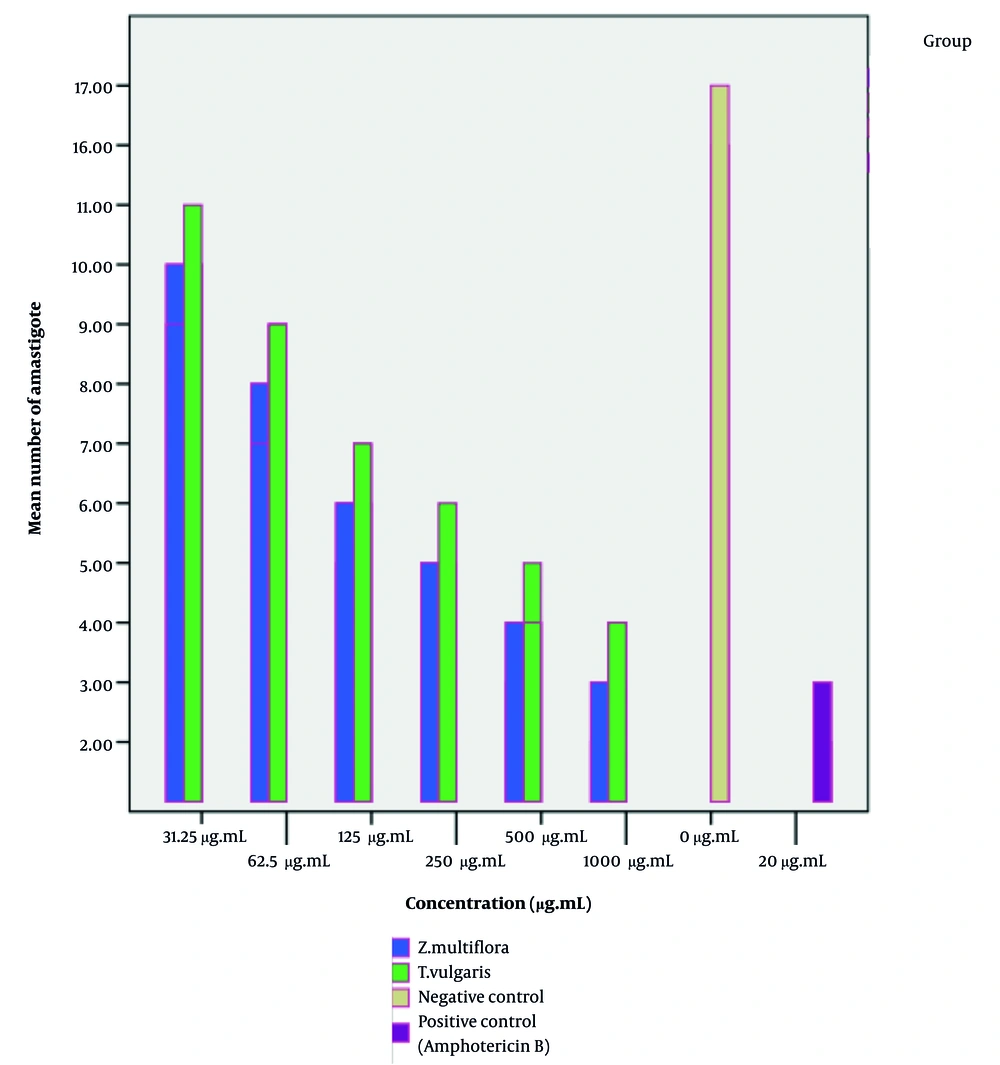

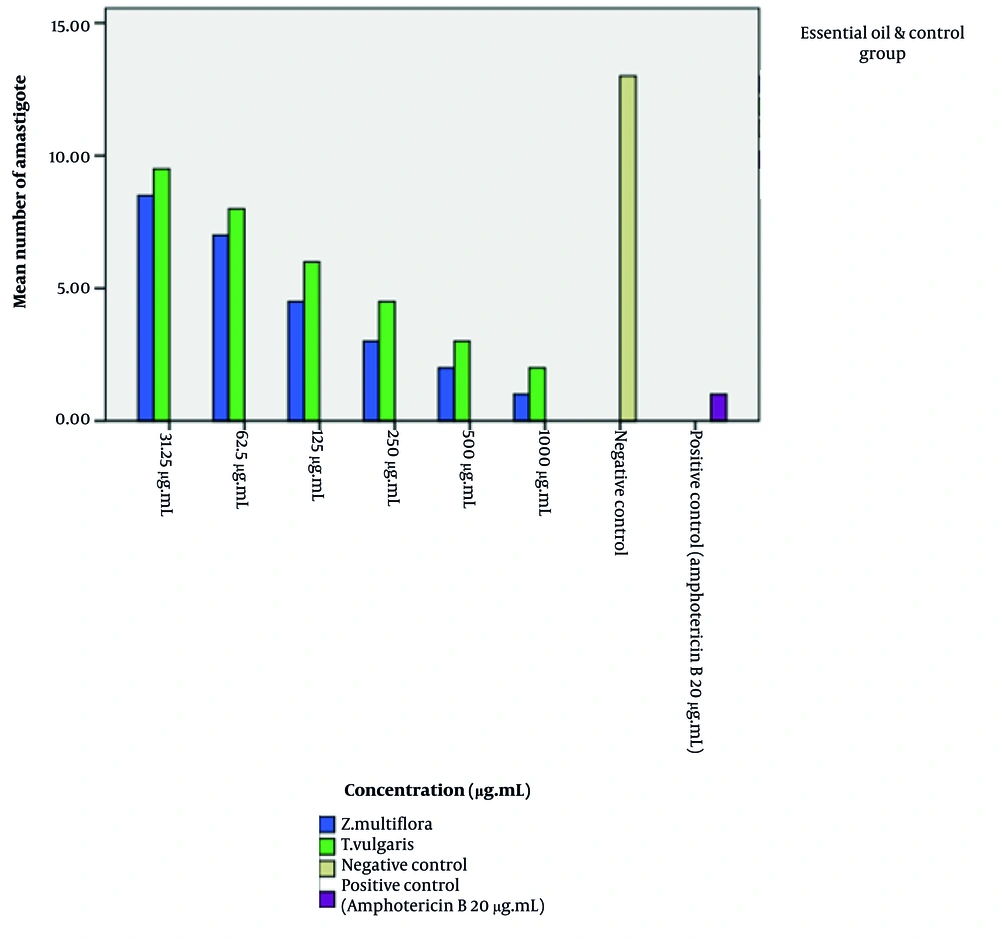

4.4. The Effect of Zataria multiflora and Thymus vulgaris Essential Oils on Leishmania major Amastigotes

Our findings indicate that the essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris exert a significant effect on intracellular amastigotes. Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test) confirmed that the essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris exhibited a significant dose-dependent reduction in the intracellular amastigote load compared to the NC (P < 0.05). As illustrated in Figures 5 and 6, the anti-amastigote activity of Z. multiflora essential oil was statistically superior to that of T. vulgaris. However, both essential oils demonstrated significantly lower efficacy in clearing the infection than the PC, amphotericin B. The IC50 values for Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris were determined to be 118.4 and 131.2 µg/mL after 24 hours, and 87.28 and 100.68 µg/mL after 48 hours of exposure to the parasite, respectively. The Selectivity Index (SI) for T. vulgaris essential oil against promastigotes and amastigotes (48 hours) was 8.84 and 8.14 µg/mL, respectively. For Z. multiflora essential oil, the SI against promastigotes and amastigotes (48 hours) was 13.39 and 9.16 µg/mL, respectively, indicating moderate selective toxicity of both essential oils towards the parasite over host cells (Table 3, Figures 5 and 6).

| Characteristic | Z. multiflora(µg.mL) | T. vulgaris(µg.mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Promastigote IC50 | 59.69 | 92.75 |

| Amastigote IC50 (48 hours) | 87.28 | 100.68 |

| Macrophage CC50 | 799.6 | 820.4 |

| SI for promastigotes | 13.39 | 8.84 |

| SI for amastigotes (48 hours) | 9.16 | 8.14 |

Abbreviations: IC50, Inhibitory Concentration; SI, Selectivity Index;

5. Discussion

5.1. Documented Bioactivities of Zataria multiflora and Thymus vulgaris

Zataria multiflora, native to central and southern Iran, has demonstrated antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic properties (14, 31). Similarly, T. vulgaris is known for its antimicrobial activities (32). One study demonstrated that treatment with Z. multiflora essential oil at a concentration of 100 μg/mL exhibited significantly higher toxicity against Leishmania tropica parasites, reducing infectivity by more than 86% in macrophages infected with Leishmania tropica amastigotes compared to the untreated control group (12). A key finding was that all tested concentrations of Z. multiflora essential oil exhibited significant antileishmanial activity against both extracellular promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania tropica in infected macrophages under in vitro conditions. Notably, the essential oil demonstrated particularly high antileishmanial efficacy against amastigotes, with a half – maximal IC50 of 8.3 μg/mL.

Similarly, in a study by Zaki et al., the antileishmanial effects of silver nanoparticles coated with T. vulgaris extract were investigated. The obtained IC50 values were 4.7 μg/mL for L. major promastigotes and 3.02 μg/mL for amastigotes, demonstrating potent activity against both parasite stages (18). In a study conducted by Youssefi et al. to investigate the effects of thymol and carvacrol on Leishmania infantum, the IC50 values for promastigotes were determined to be 7.2 and 9.8 µg/mL, respectively (33). These studies demonstrated the efficacy and therapeutic value of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris extracts and compounds against other Leishmania species.

5.2. Key Findings and Chemical Basis of the Present Study

However, despite these encouraging findings, a comprehensive understanding of the direct antileishmanial efficacy of the essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris specifically against L. major, a highly relevant species in our region, remains to be fully elucidated. In another study conducted by Barati et al., the antileishmanial effects of the hydroalcoholic extract of Z. multiflora against L. major were investigated. Their results demonstrated that the extract significantly inhibited the growth of promastigotes, with a half–maximal IC50 of 7.4 mg/mL (34).

Our study highlights the potential of essential oils from Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris as promising anti-leishmanial agents. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis revealed that thymol and carvacrol were the major bioactive compounds, known for their antimicrobial and antiparasitic effects. In vitro assays demonstrated significant dose-dependent inhibition of L. major promastigotes, with IC50 values of 59.69 µg/mL for Z. multiflora and 92.75 µg/mL for T. vulgaris. The cytotoxicity assessments on J774 macrophages further supported the safety profile of these essential oils, with CC50 values of 799.6 µg/mL for Z. multiflora and 820.4 µg/mL for T. vulgaris. The findings of this study also revealed that the IC50 values for the essential oils of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris after 48 hours of exposure to L. major amastigotes were 87.28 and 100.68 µg/mL, respectively.

In light of the aforementioned study, it can be concluded that the antileishmanial effects of these plants are likely due to the presence of these active compounds. Additionally, their study demonstrated that the tested compounds exhibited the highest growth inhibition at higher concentrations. In our study, the highest inhibition of parasite growth was observed at higher concentrations, which may corroborate previous findings reported in the literature.

5.3. Comparison with Existing Literature and Potential Mechanisms

This indicates a therapeutic window that could be beneficial for further development in clinical settings, aligning with the growing interest in natural products as alternatives to synthetic pharmaceuticals. The observed cytotoxicity levels suggest that while these essential oils exert significant anti-parasitic effects, they also retain the potential for safety in therapeutic applications. The antileishmanial effects of these essential oils may be attributed to their complex chemical compositions, which likely act synergistically (35, 36). This synergy is not limited to the dominant phenols; other major components such as γ-terpinene and p-cymene are known to exert membrane-perturbing and pro-oxidant effects, while terpinene-4-ol can disrupt mitochondrial function. The presence of (E)-caryophyllene may also contribute to a potential immunomodulatory response (37, 38). Previous studies have shown that the combination of multiple bioactive compounds can lead to improved therapeutic outcomes. Thymol and carvacrol, in particular, are known to disrupt cell membrane integrity and induce oxidative stress in parasites (39-41).

The proposed mechanism involves the interaction of these phenolic compounds with the phospholipid bilayers of the parasite's cell membrane, increasing its permeability and leading to the leakage of vital intracellular components such as potassium ions, proteins, and nucleotides, ultimately causing cell lysis (42, 43). Furthermore, these compounds can disrupt mitochondrial function by collapsing the mitochondrial membrane potential, a critical step for ATP production, thereby depriving the parasite of energy (33). These compounds may also act by inhibiting key enzymes in protozoal metabolism, including dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR).

The inhibition of DHFR leads to the depletion of cellular folate reserves, as this enzyme plays a vital role in producing tetrahydrofolate, a precursor for cofactors essential in the synthesis of purines, dTTP, and amino acids. Ultimately, this process results in the cessation of cell proliferation and cell death (44, 45). Another key mechanism is the induction of an apoptotic-like death pathway in Leishmania parasites, characterized by phosphatidylserine externalization, DNA fragmentation, and activation of caspase-like proteases (46, 47). The lipophilic nature of thymol and carvacrol facilitates their penetration into the parasite, enabling these multi-faceted attacks. This multi-target mechanism is advantageous as it reduces the likelihood of the development of parasite resistance, a significant limitation of current single-target drugs (48).

5.4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the anti-leishmanial potential of essential oils from Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris against L. major. In vitro tests demonstrated effective dose-dependent inhibition of L. major promastigotes and amastigotes, with low toxicity observed in J774 macrophages, indicating a favorable safety profile. These findings suggest that these essential oils could be promising natural alternatives for leishmaniasis treatment, especially given the challenges of drug resistance and side effects with current therapies. Further in vivo studies are needed to validate their therapeutic potential.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Given the ongoing challenges associated with conventional leishmaniasis therapies, including drug resistance and adverse effects, the exploration of these natural alternatives is timely and necessary. However, this study was limited to in vitro experiments, and further in vivo studies are needed to validate these findings. Future research should also explore the formulation of these essential oils for topical or systemic use in clinical settings.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the potential of Z. multiflora and T. vulgaris essential oils as effective and safe alternatives for leishmaniasis treatment. Continued research into their mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications is essential to address the global burden of this neglected tropical disease. The identification of their bioactive compounds and the elucidation of their mechanisms of action remain critical areas for future exploration, with the ultimate goal of improving health outcomes for affected populations.