1. Background

Viral components of SARS-CoV-2 exhibit diverse functions in host–pathogen interactions and have been the focus of extensive investigation since the onset of the pandemic. These viral elements are generally classified into structural, nonstructural, and accessory proteins (1-3). Among them, the spike protein has been shown to enhance the expression of its receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), in bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells, thereby facilitating viral entry (4, 5). Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have further demonstrated ACE2 expression in lung type II pneumocytes, ileal absorptive enterocytes, nasal goblet secretory cells, and bronchial epithelial cells (6). Co-expression of viral entry-related genes has been observed in respiratory, corneal, and intestinal epithelia, underscoring their roles in transmission and tissue tropism (7, 8). Overall, ACE2 abundance appears to be a key determinant of infectivity, and its spike-induced upregulation may further enhance viral invasion (9, 10). Therefore, the functions of SARS-CoV-2 proteins during infection warrant re-evaluation, particularly in the context of in vivo models.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and elevate inflammatory biomarkers. Beyond the respiratory system, the virus also infects the gastrointestinal tract, which may serve as an additional replication site with important clinical implications (11). The gut-lung axis has emerged as a potential contributor to COVID-19 pathogenesis. Structural and nonstructural viral proteins play distinct roles in disease development, while dysregulated immune responses (marked by elevated IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) are key drivers of systemic inflammation and COVID-19 severity (12, 13). Chronic inflammation drives tumor progression, including in colorectal cancer, yet the impact of viral components like the spike protein on healthy versus cancerous epithelia is unclear. Clarifying these cytokine responses may reveal mechanisms of tissue injury and tumor microenvironment changes (14).

2. Objectives

This study therefore evaluates how the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein modulates key proinflammatory cytokines in lung and colon epithelial cells.

3. Methods

3.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

This study utilized two human epithelial cell lines: BEAS-2B (human bronchial epithelial cells) and CRL-1831 (colon epithelial cells). BEAS-2B cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) according to the supplier’s protocol. CRL-1831 cells were maintained in ATCC-formulated RPMI-1640 Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 (15, 16).

3.2. Cell Viability Assay

To evaluate cell proliferation, the XTT assay based on the sodium salt of benzene sulfonic acid hydrate was employed. CRL-1831 cells and BEAS-2B epithelial cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well and incubated for 24 hours to allow for cell attachment and stabilization. Following incubation, CRL-1831 cells and BEAS-2B epithelial cells were treated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Elabscience Bionovation Inc) at the determined doses (0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 ng/mL) for 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Control groups received medium only. Experiments were conducted in triplicate for each condition. After each treatment period, 50 µL of XTT reagent (1 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 hours. The resulting formazan product was quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Synergy H1, BioTek Instruments, USA) (17).

3.3. RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from treated and control cells using TRIzol reagent (ABP Biosciences, China) and RNA integrity was verified by spectrophotometry (Biotek Synergy HT). Reverse transcription was performed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using SYBR Green master mix on a real-time PCR system (Roche Diagnostic Systems, USA). Primers targeting glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were utilized. Gene expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were analyzed. The GAPDH was used as an internal control gene. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (18). Primer sequences are detailed in Table 1.

| Genes | Forward Primers | Reverse Primers |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 5′-CTCCACAAGCGCCTTCGGT-3′ | 5′-GAATCTTCTCCTGGGGGTACTGG-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-GCCCATGTTGTAGCAAACCCTC-3′ | 5′-GGTTATCTCTCAGCTCCACGCC-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′ | 5′-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3′ |

| IL-1β | 5’-CGAATCTCCGACCACCACTA-3' | 5’-AGCCTCGTTATCCCATGTGT-3' |

| IFN-γ | 5’-GCTGTTACTGCCAGGACCC-3' | 5’-TTTTCTGTCACTCTCCTCTTTCC-3’ |

3.4. Protein Quantification

Culture supernatants collected at each time point were analyzed for cytokine concentrations using ELISA kits specific for IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 (ELK Biotechnology, USA). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Concentrations were determined based on standard curves generated for each cytokine (19).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with great care for each experiment, all of which were conducted at least in triplicate. Data processing was carried out using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0.1, USA). Comparisons between treated and untreated cell optical density values were evaluated using two-tailed t-tests, with statistical significance defined as P ≤ 0.05. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additional statistical significance levels are shown as follows: *P ≤ 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

4. Results

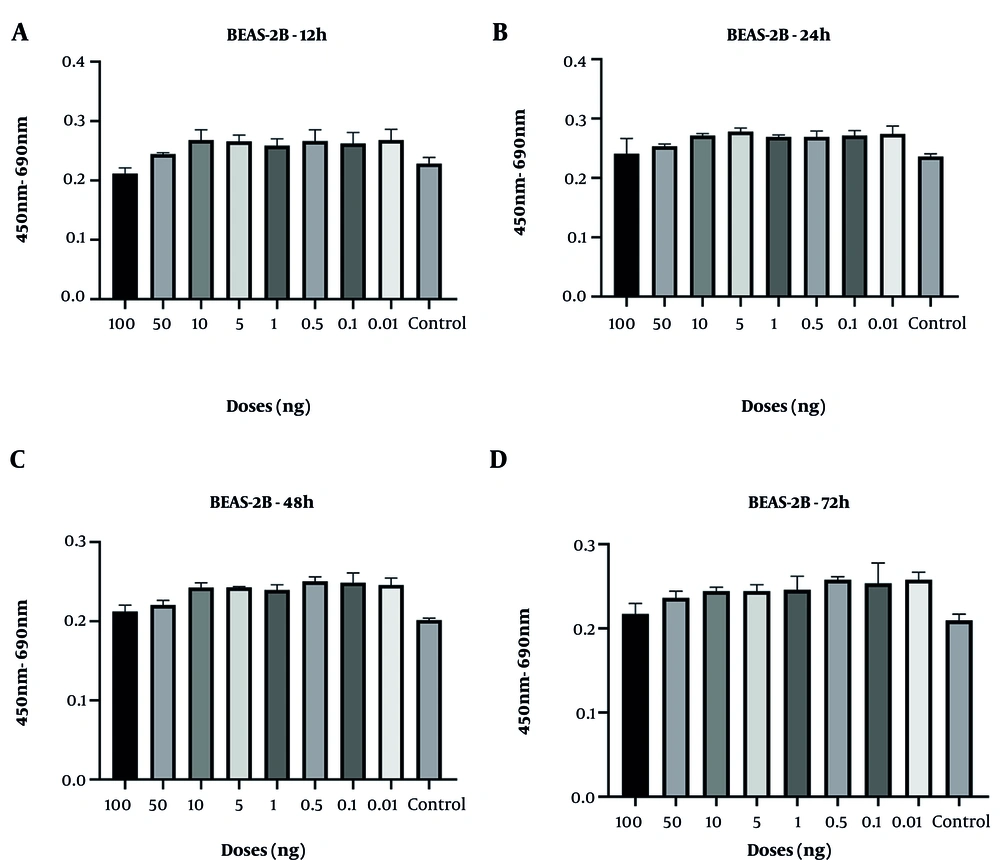

4.1. Cell Viability in BEAS-2B and CRL-1831 Cells Treated with Spike Protein

Cell viability analyses demonstrated that the control group of BEAS-2B epithelial cells and CRL-1831 colon epithelial cells exhibited a natural decline over time, particularly at 48 and 72 hours. In BEAS-2B cells, spike protein treatment resulted in a modest increase in viability at the 48-hour time point, although this effect was not sustained at 72 hours. At the highest concentration (100 ng/mL), an early increase at 24 hours was followed by a decline at later time points (Figure 1). However, none of these fluctuations reached statistical significance at any dose or time point.

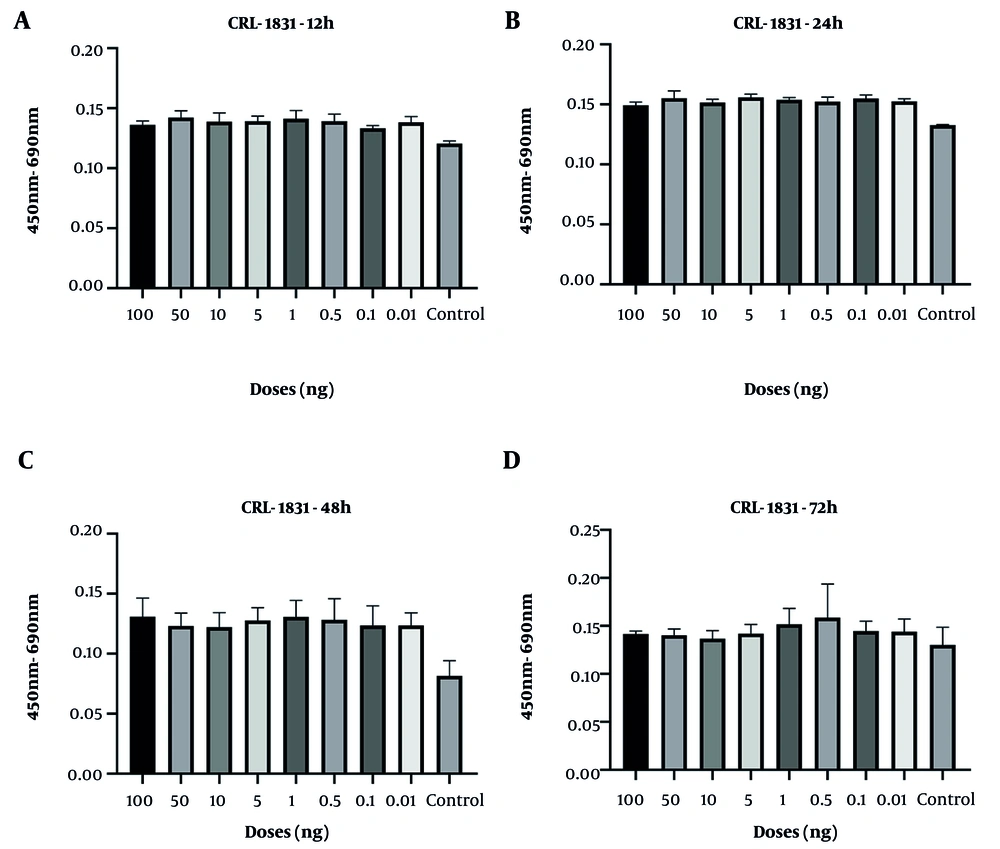

In CRL-1831 cells, spike protein exposure produced an early elevation in cell viability at 12 hours, whereas a reduction became evident at 48 hours (Figure 2). Across all tested doses, no cytotoxicity was observed, indicating that the spike protein did not adversely affect cell survival under the experimental conditions. Consistently, no statistically significant changes in viability were detected at any concentration or incubation period.

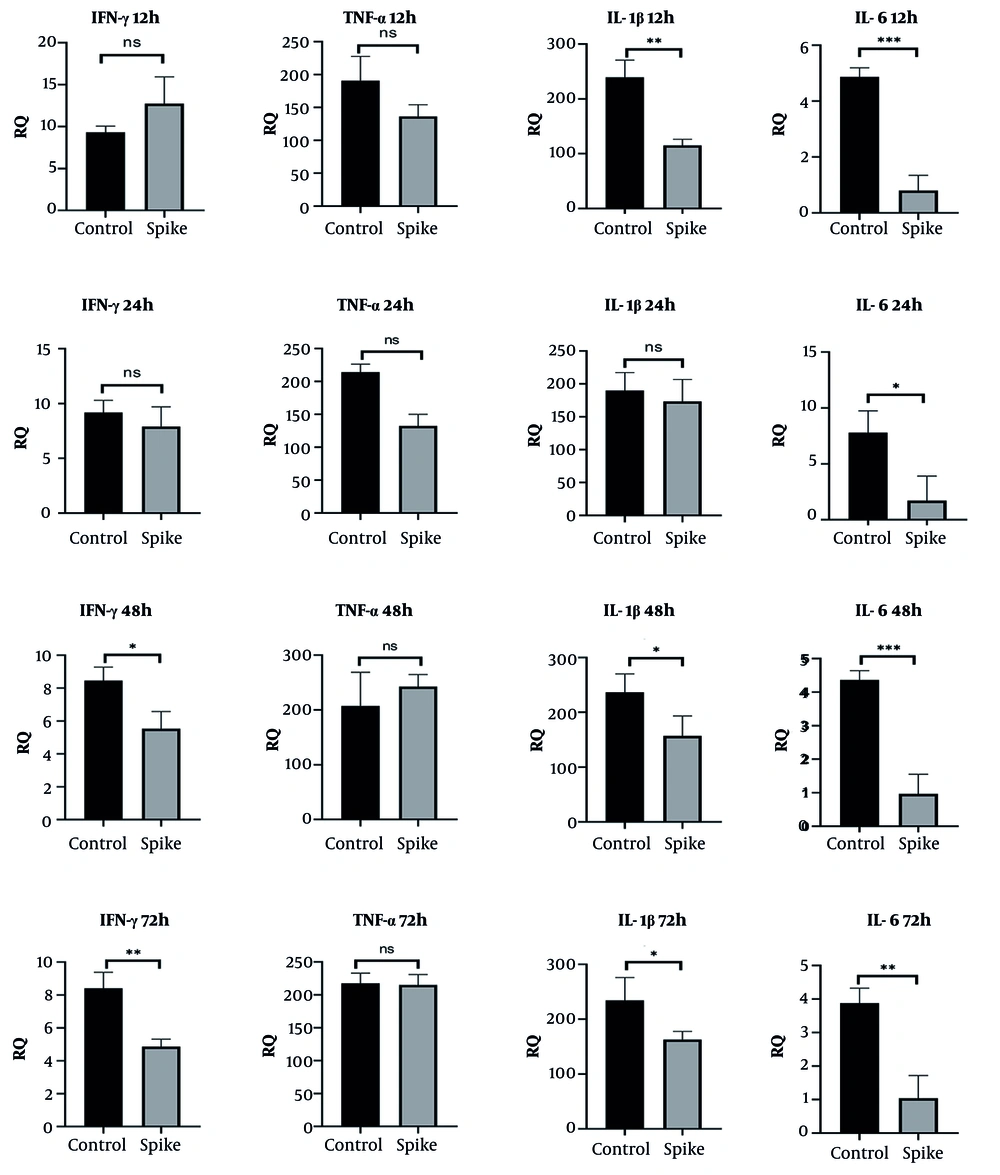

4.2. Time-Dependent Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein on Immune Gene Expression in BEAS-2B Cells

Spike protein treatment led to a transient increase in IFN-γ mRNA levels at 12 hours, followed by a significant reduction at 48 (P < 0.05) and 72 hours (P < 0.01). TNF-α expression remained relatively unchanged throughout the treatment period. IL-1β expression showed a progressive decrease across all time points, aligning with a time-dependent suppression pattern. Similarly, IL-6 mRNA levels were consistently reduced at each measured interval, suggesting an overall dampening of inflammatory gene activation in BEAS-2B cells (12 h: P < 0.001, 24 h: P < 0.05, 48 h: P < 0.01, and 72 h: P < 0.01; Figure 3).

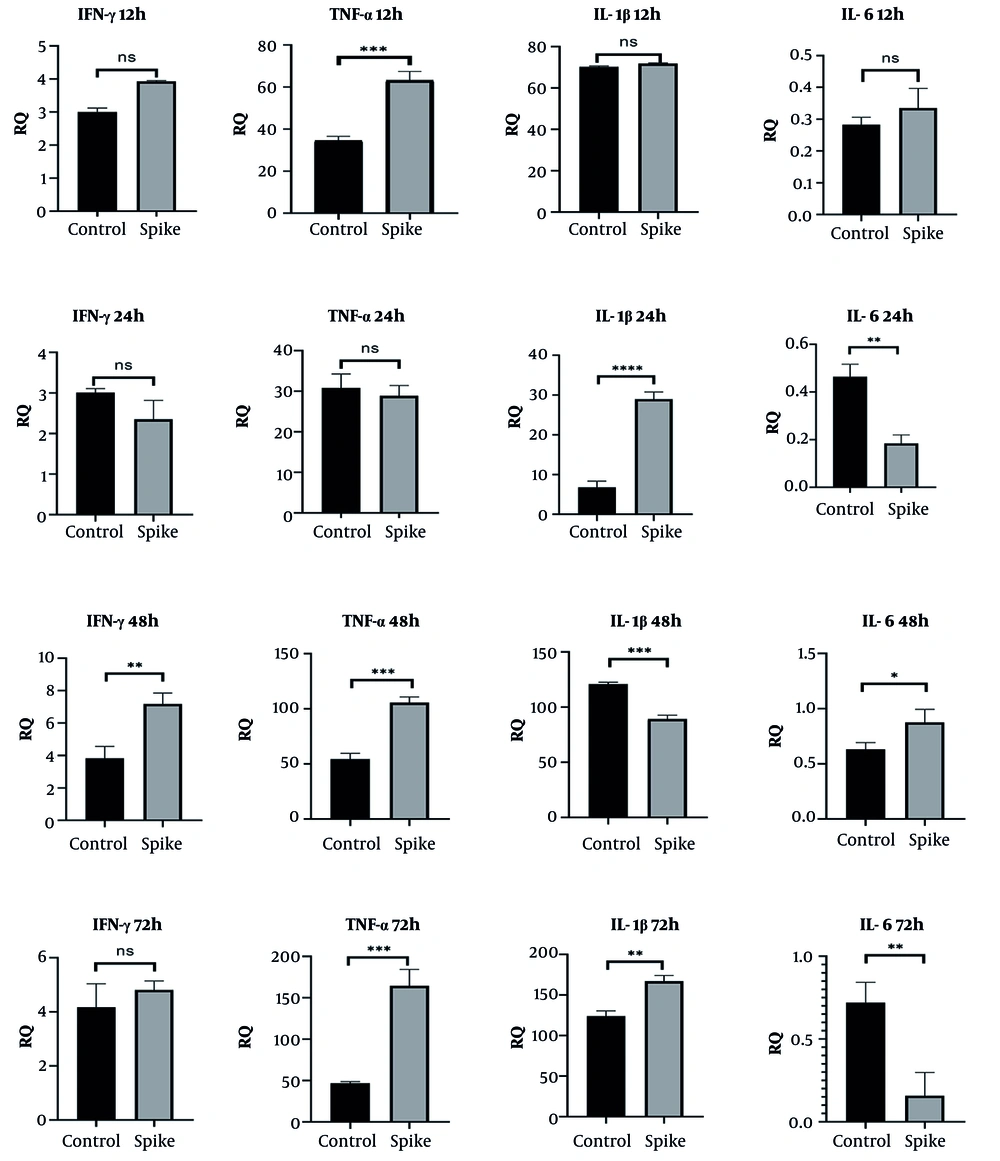

4.3. Time-Dependent Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein on Immune Gene Expression in CRL-1831 Cells

CRL-1831 cells demonstrated a different transcriptional pattern in response to spike protein. IFN-γ expression significantly increased at 48 and 72 hours, while TNF-α levels were elevated at 12, 48, and 72 hours. IL-1β expression was also upregulated at 24 and 48 hours. IL-6 expression exhibited a complex pattern, showing reduced levels at 24 and 72 hours while displaying a marked increase at 48 hours, which indicates a fluctuating inflammatory response distinct from that observed in lung epithelial cells (Figure 4).

Gene expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in CRL-1831 colon epithelial cells following 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h spike protein treatment (statistical significance levels are shown as follows: * P ≤ 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001; abbreviation: ns, not significant).

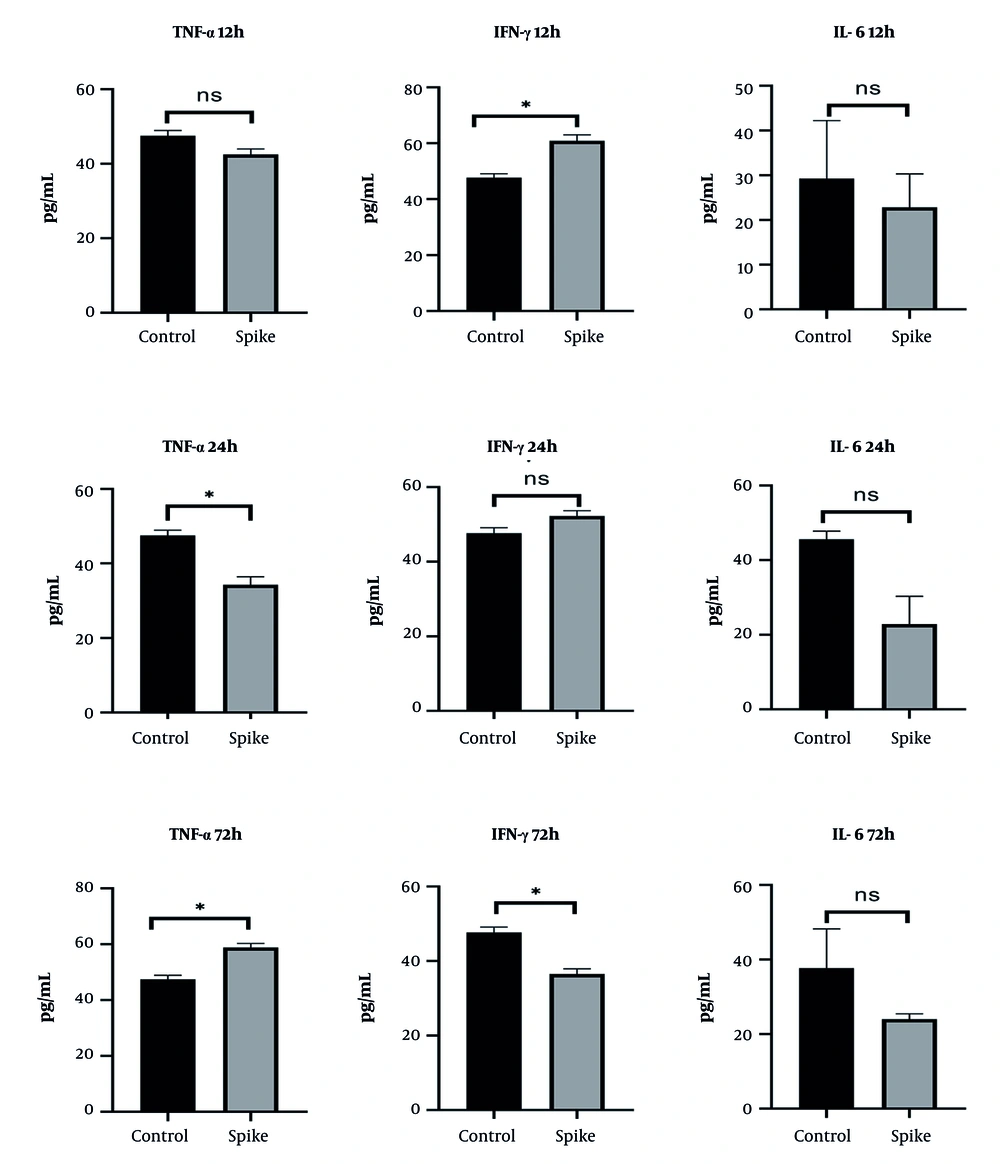

4.4. Proinflammatory Cytokine Secretion in CRL-1831 Cells

In CRL-1831 cells, spike protein exposure produced a reduction in TNF-α levels at 24 hours, followed by an increase at 72 hours. IFN-γ secretion showed an early rise at 12 hours but decreased substantially by 72 hours. IL-6 concentrations displayed an overall decreasing trend across the evaluated time points (Figure 5). These secretion profiles were consistent with the gene expression patterns, particularly the delayed proinflammatory response.

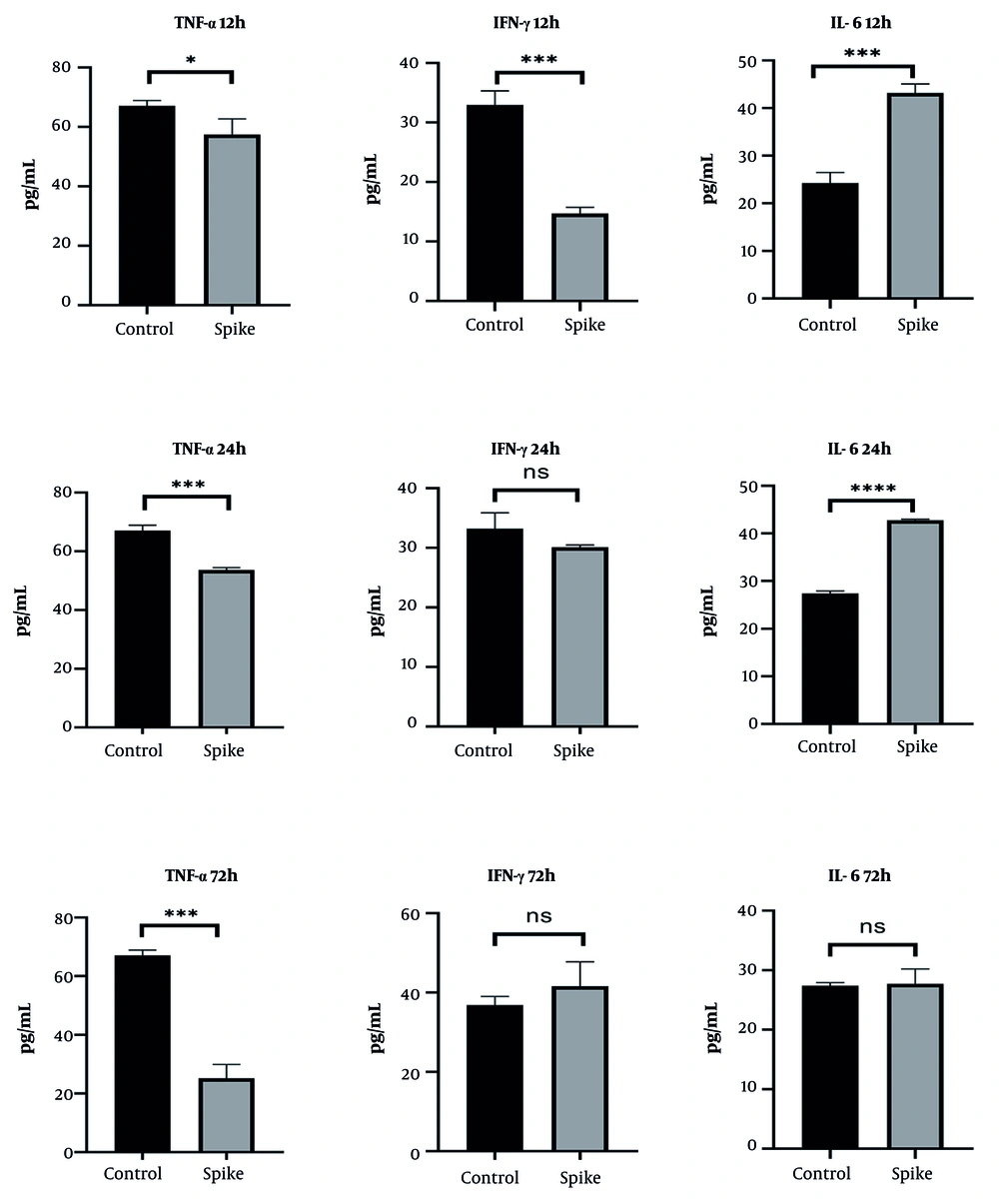

4.5. Proinflammatory Cytokine Secretion in BEAS-2B Cells

In BEAS-2B cells, TNF-α secretion decreased progressively in a time-dependent manner following spike protein treatment. IFN-γ levels were reduced at 12 hours but increased at later time points, suggesting delayed compensatory activation. IL-6 secretion increased during the early phases (12 and 24 hours), then returned to baseline by 72 hours (Figure 6).

5. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 remains a major global concern due to its ability to trigger strong inflammatory responses and affect multiple organs beyond the respiratory tract, including the gastrointestinal epithelium. In the lungs, excessive cytokine release (cytokine storm) contributes significantly to severe disease and mortality (20, 21). Individuals with autoimmune disorders are also at higher risk because of immunosuppressive treatments (22, 23). NF-κB is a central regulator of inflammation and immune responses and is known to be persistently activated in COVID-19 (24, 25). The spike protein can activate TLR2-MyD88-NF-κB signaling and induce cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α (26). Delayed cytokine patterns may reflect feedback regulation within NF-κB and interferon pathways. The stronger and more sustained inflammatory response observed in colon cells may be due to tissue-specific receptor expression or different signaling thresholds (27-29).

In this study, we demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 spike protein differentially modulates proinflammatory genes and cytokine expression in human lung and colon epithelial cells in a time-dependent manner. In BEAS-2B cells, the early increase in IFN-γ and IL-6 mRNA levels followed by their subsequent downregulation at 48 and 72 hours aligns with prior findings indicating an initial hyperinflammatory reaction that becomes suppressed as the infection progresses or as regulatory mechanisms activate. Interestingly, IL-1β was consistently downregulated in BEAS-2B cells, potentially reflecting a dampened inflammasome response in airway epithelial cells (30). On the contrary, CRL-1831 colon epithelial cells demonstrated more sustained and even delayed elevations in IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β mRNA, particularly at 48 and 72 hours, suggesting a different regulatory kinetics. This is congruent with clinical reports of prolonged gastrointestinal inflammation in COVID-19 patients (31). The observed IL-6 fluctuations (initial suppression followed by a spike) suggest a biphasic response or the involvement of feedback mechanisms distinct from those in the lung epithelium.

BEAS-2B cells exhibited an early IFN-γ response followed by progressive suppression, aligning with previous findings suggesting immune exhaustion or feedback inhibition in lung epithelial cells during prolonged viral exposure. The consistent downregulation of IL-6 and IL-1β further supports an overall immunosuppressive effect of prolonged spike protein exposure in lung tissue, which may impair effective antiviral responses and contribute to disease progression. Moreover, the inflammatory effects of spike treatment occurred without indications of cell damage at the tested concentrations. Due to the diverse organ tropisms observed in SARS-CoV-2 infections involving various organs, the virus utilizes multiple receptors and co-receptors. Host entry factors such as ACE2, TMPRSS2, Furin, heparan sulfate, and CD147 are known to shape SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and determine epithelial susceptibility. Differences in the expression of these molecules across tissues may therefore help explain the distinct inflammatory patterns observed in lung and colon cells in our study. Moreover, demographic factors including age, sex, and smoking status have been reported to influence ACE2, TMPRSS2, and CTSL expression levels, further contributing to variability in viral tropism and disease severity.

Recent studies indicate that spike protein can modulate epithelial inflammatory pathways through ACE2 dependent entry, host-factor–mediated cell tropism, and TLR-mediated immune activation (32, 33). Additionally, both viral and synthetic spike proteins have been implicated in endothelial dysfunction, which is a key driver of vascular complications in COVID-19. Spike protein can directly bind to ACE2 on endothelial cells, leading to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and thrombosis. Such endothelial damage has also been associated with atypical lymphoid proliferation in various tissues, contributing to persistent immune dysregulation in long COVID and other post-infectious syndromes (34).

Recent studies show that the spike protein can activate endothelial and thrombo-inflammatory pathways, particularly through the C3a/C3aR axis, suggesting C3aR as a potential therapeutic target (35). Other reports indicate that spike protein promotes inflammation and EMT in lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts by upregulating GADD45A, highlighting additional pathways relevant to spike-induced injury (28). Although endothelial mechanisms were not assessed here, the delayed and sustained cytokine responses observed in colon cells may have downstream epithelial-vascular implications.

In this context, our findings indicate that the spike protein alone acts as an immunomodulatory stimulus capable of inducing prolonged epithelial stress responses, which may contribute to secondary endothelial and lymphoid alterations.

A limitation of this study is that all experiments were performed using immortalized epithelial cell lines (BEAS-2B and CRL-1831), which lack the complexity of in vivo tissue architecture and immune-epithelial interactions. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as cell-line specific responses rather than fully representative of human tissues. Validation using primary epithelial cells, co-culture or organoid models, and clinical samples will be essential to confirm the translational relevance of these findings. Second, the study focused solely on cytokine expression and did not evaluate upstream signaling pathways that may mediate these responses. Mechanistically relevant pathways including NF-κB, TLR-related signaling, GADD45A associated EMT induction, and complement-driven endothelial activation were not examined. Addressing these pathways in future studies, together with models incorporating epithelial-immune interactions, will help clarify the molecular basis of spike protein-induced inflammatory responses.

Protein-level cytokine measurements via ELISA confirmed these expression trends. The spike protein triggered a general suppression of proinflammatory cytokines in BEAS-2B cells over time, while CRL-1831 cells showed a delayed but marked increase in TNF-α and IFN-γ secretion. These findings underscore the ability of the spike protein to independently modulate local inflammatory responses in non-immune cells.

5.1. Conclusions

This study shows that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alone can differentially modulate inflammatory responses in lung and colon epithelial cell lines in a time-dependent manner. These findings underscore the tissue-specific immunomodulatory effects of the spike protein and may help explain organ-level differences in COVID-19 pathology. Further studies are needed to clarify the underlying signaling mechanisms and the consequences of prolonged spike exposure.