1. Background

Substance use disorders (SUDs) represent a significant and growing public health crisis, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where treatment resources are limited (1). In Egypt, recent epidemiological data reveal alarming increases in cannabis and prescription drug misuse, with emerging patterns of polydrug use complicating treatment efforts. A particularly challenging aspect of SUDs is agitation behavior, which affects approximately 34% of patients in Egyptian treatment centers and significantly worsens clinical outcomes (2).

The neurobiological basis of agitation in SUD patients involves dysregulation of prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuitry, where chronic substance use impairs emotional regulation while heightening stress reactivity. This explains why traditional abstinence-focused approaches often fail — they do not address the underlying emotional dysregulation that drives both substance use and agitated behaviors (3). The cyclical nature of this relationship creates substantial barriers to treatment adherence, as patients frequently relapse when unable to manage distressing emotional states without substances (4).

Clinically, agitation manifests along a severity continuum from restlessness to physical aggression, leading to safety concerns and high dropout rates. Current pharmacological approaches, while providing immediate symptom control, often prove inadequate for long-term management due to side effects and limited impact on behavioral components (5). These challenges are exacerbated in Egypt by critical shortages of addiction specialists and persistent stigma surrounding mental health treatment (2).

Developing effective interventions requires addressing three key dimensions: Neurobiological changes from chronic substance use, culturally relevant behavioral strategies, and implementation feasibility in resource-limited settings (6). Our rehabilitation program addresses these needs by combining self-directed evidence-based cognitive techniques (7) with culturally adapted components like family support and spiritual coping (8). By addressing both biological and psychosocial factors, this study contributes to advancing comprehensive care models for patients with SUD by evaluating the effectiveness of a targeted rehabilitation program designed to reduce agitation.

1.1. Hypothesis and Research Question

Based on the aim of the study to evaluate the effect of a rehabilitation program on agitation behavior among patients with SUD, the following hypotheses and research questions were formulated:

- Hypothesis 1: There is a significant reduction in agitation behavior scores after participation in the rehabilitation program among patients with SUD.

- Research question: Are the selected sociodemographic characteristics associated with the severity of agitation behavior among patients with SUD before and after the rehabilitation program?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This quasi-experimental study used a single-group pretest-posttest design and followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement guidelines. Randomization was not applied due to ethical concerns about withholding treatment from a high‑risk population, practical constraints related to clinic-based recruitment, where all eligible patients required intervention, and the need to evaluate a newly developed, culturally adapted rehabilitation protocol.

2.2. Setting and Sampling

The study was conducted at the outpatient clinics of the Okasha Institute of Psychiatry in Egypt between March and September 2024. The required sample size was calculated using Rosner's (2016) formula for paired-sample comparisons to achieve 80% statistical power at a 5% significance level (two-sided). A pilot study with five similar patients yielded an estimated standard deviation of the differences (SΔ = 1.14), and the expected effect size was E/SΔ = 0.3962. Using Zα = 1.9600 and Zβ = 0.8416, the constants were calculated as B = (Zα + Zβ)2 = 7.8489 and C = (E/SΔ)2 = 0.1570, yielding a required sample size of N = B/C ≈ 50. Accordingly, 50 participants were recruited using purposive sampling. Eligible participants were Arabic-speaking adults aged 18 - 45 years, diagnosed with SUD according to DSM-5 criteria, drug-free for at least one month before enrollment, and without co-occurring psychiatric disorders. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving an explanation of the study objectives and procedures.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

Three standardized tools were used to collect comprehensive data for this study. First, a demographic and clinical characteristics form was developed to capture essential participant information. This form collected personal details, including age, gender, and marital status, as well as socioeconomic factors such as education level, occupation, and monthly income. It also documented substance use history, including age of initiation, types of substances used, and administration methods, as well as family history of substance abuse. The form consisted of 17 closed-ended questions with multiple-choice response options, and its content validity was confirmed through rigorous review by five psychiatric nursing experts.

The Drug Abuse Screening Test [DAST-10; Skinner, 1982 (9)] served as a reliable screening tool for substance use patterns and related problems. This 10-item questionnaire assessed nonmedical drug use, negative consequences of use, and difficulties in controlling substance use. Scoring followed established guidelines, with total scores categorized into five severity levels ranging from no problem (0 points) to severe (9 - 10 points). All participants had a confirmed diagnosis of SUD established by a qualified psychiatrist using DSM‑5 criteria before enrolment. This psychiatric confirmation served as a clinical verification of the substance use history. The DAST-10 served as a reliable screening tool for substance use patterns and related problems. To minimize potential self-report bias and encourage honest disclosure, several strategies were implemented during the administration of the DAST-10. These included explicitly emphasizing the confidentiality and anonymity of all responses, assuring participants that their answers would not affect their clinical care, and creating a trusting and non-judgmental environment by trained research staff. Supplementary methods such as laboratory toxicology screening or collateral family interviews were not used due to ethical, logistical, and budgetary constraints.

2.4. Tool Validation and Adaptation

All study instruments underwent rigorous validation for cultural and clinical appropriateness in the Egyptian context. The Arabic versions were developed through a multi‑stage process: (1) Forward‑translation by bilingual psychiatrists, (2) back‑translation by independent linguists, and (3) expert review by five addiction specialists to confirm content validity. The content validity of the tools was quantitatively assessed. The Content Validity Index (CVI) was 0.92, and the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was 0.89, both exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.70, confirming accepted content validity.

The Agitated Behavior Scale (ABS) represents a modified version of the Modified Aggression Questionnaire (41‑item version), which demonstrated excellent internal consistency during pilot testing with 5 participants (10% of the target sample), with Cronbach's α = 0.84 for the total scale, meeting reliability thresholds without requiring item modifications. Pilot testing also confirmed that all tools were comprehensible (100% of participants completed questionnaires without requesting clarifications) and feasible to administer within clinic time constraints.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was not conducted in the present study due to the relatively small sample size (n = 50), which is below the recommended participant‑to‑item ratio (5 - 10:1) for stable factor solutions. Additionally, the study's primary focus was on evaluating the effect of the nursing intervention program rather than performing a full psychometric validation. Future research with a larger Egyptian sample is recommended to conduct CFA and report structural validity indices such as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

2.5. Intervention

The structured rehabilitation program comprised nine group sessions, each lasting 45 minutes, conducted over four months (April - August 2024). Participants were stratified by their initial agitation levels (low, moderate, high) to tailor intervention delivery. The program covered psychoeducation on SUDs and addiction, education on agitation and aggression, anger management strategies (e.g., physical exercises, muscle relaxation), coping techniques (e.g., deep breathing, sleep hygiene), cognitive-behavioural methods for challenging negative thoughts, and problem-solving skills training. Sessions were sequentially organized, beginning with knowledge-building and progressing to skill application. A standardized manual guided implementation to ensure consistency, while participants received handouts and between-session practice tasks to reinforce learning.

2.6. Procedure of Data Collection

Data collection was conducted in three phases. Baseline assessment (March - April 2024) involved administering the demographic form, DAST-10, and the ABS in Arabic at the clinic, with research staff available to clarify items. Intervention delivery (April - August 2024) consisted of nine structured group sessions held twice weekly. Post-intervention assessment (September 2024) repeated the same tools one month after program completion. To ensure quality control, all questionnaires were checked for completeness immediately after administration, and research assistants received training to deliver instruments consistently while maintaining a neutral stance.

2.7. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages) were used to summarize demographic, clinical, and outcome variables. Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of histograms. For within-group changes from pre- to post-intervention, paired-samples t-tests were used for normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for non-normally distributed data. Between-group comparisons were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for baseline (pre-intervention) scores. To meet ANCOVA assumptions and ensure adequate group sizes, several sociodemographic and clinical variables were recoded into broader categories: Age (< 36 vs. ≥ 36 years), education (low vs. higher), marital status (not married vs. married), duration of drug use (≤ 5 vs. > 5 years), number of inpatient treatments (≤ 2 vs. ≥ 3), and relapse history (1 - 2 vs. ≥ 3 times). These recoded variables were used as fixed factors in the ANCOVA.

Due to small subgroup sizes in certain demographic variables, which may violate ANCOVA assumptions and reduce statistical power, categories were collapsed into broader, analytically meaningful groups. Age was grouped into < 36 years and ≥ 36 years; education was dichotomized into low education (cannot read/write, can read/write, intermediate education) and higher education (university/postgraduate); marital status was categorized as not currently married (single/divorced) and currently married; duration of drug use was recoded as short-term (≤ 5 years) and long-term (> 5 years); number of inpatient treatment episodes as ≤ 2 times and ≥ 3 times; and relapse history as 1 - 2 times and ≥ 3 times. These recodings allowed for more robust statistical comparisons while preserving interpretive relevance. Interaction terms were included in the full ANCOVA model to examine combined demographic effects. For non-parametric confirmation, Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted for between-group comparisons. Effect sizes were reported as Cohen's d for t-tests and partial eta squared (η2) for ANCOVA. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ain-Shams University Research Ethics Committee (No. 24.07.335) in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Before enrolment, all participants provided written informed consent detailing: (1) Research aims, (2) voluntary participation with withdrawal rights, (3) confidentiality protections (anonymous IDs, encrypted digital storage), and (4) session recording procedures. No financial compensation was offered to avoid coercion. Special precautions were taken for agitated patients, including on-call psychiatric support during assessments. All data will be retained for 5 years per institutional policies before secure destruction.

3. Results

McNemar's test revealed significant reductions in eight of ten drug use–related behaviours after rehabilitation, including nonmedical use, polydrug use, inability to stop, blackouts, family complaints, neglect of responsibilities, and illegal activities (all P < 0.001). Guilt feelings showed a nonsignificant improvement (P = 0.096), while withdrawal symptoms (P = 1.000) and medical problems (P = 0.549) showed no change (Tables 1 and 2).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 18 < 27 | 8 (16.0) |

| 27 < 36 | 23 (46.0) |

| 36 - 45 | 19 (38.0) |

| Mean ± SD | 33.39 ± 6.81 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 28 (56.0) |

| Married | 14 (28.0) |

| Divorced | 8 (16.0) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 1 (2.0) |

| Read and write | 8 (16.0) |

| Intermediate | 16 (32.0) |

| University | 18 (36.0) |

| Postgraduate | 7 (14.0) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 12 (24.0) |

| Student | 15 (30.0) |

| Manual labour | 21 (42.0) |

| Administrative work | 2 (4.0) |

| Monthly income | |

| Insufficient | 31 (62.0) |

| Sufficient | 15 (30.0) |

| More than sufficient | 4 (8.0) |

| Residence | |

| Alone | 12 (24.0) |

| With parents | 34 (68.0) |

| With spouse/children | 4 (8.0) |

| Residence location | |

| Rural | 18 (36.0) |

| Urban | 32 (64.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

| No. | Drug Use-Related Behaviour | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | McNemar's Exact P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Q1 | Using drugs other than those required for medical reasons | 44 (88.0) | 6 (12.0) | 11 (22.0) | 39 (78.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q2 | Using more than one drug at a time | 39 (78.0) | 11 (22.0) | 10 (20.0) | 40 (80.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q3 | Able to stop using drugs when you want to | 30 (60.0) | 20 (40.0) | 11 (22.0) | 39 (78.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q4 | Having "blackouts" or "flashbacks" because of drug use | 33 (66.0) | 17 (34.0) | 9 (18.0) | 41 (82.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q5 | Feeling bad or guilty about drug use | 25 (50.0) | 25 (50.0) | 33 (66.0) | 17 (34.0) | 0.096 |

| Q6 | Spouse (or parents) ever complained about your involvement with drugs | 40 (80.0) | 10 (20.0) | 15 (30.0) | 35 (70.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q7 | Neglecting the family because of drug use | 38 (76.0) | 12 (24.0) | 11 (22.0) | 39 (78.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q8 | Having engaged in illegal activities to obtain drugs | 23 (46.0) | 27 (54.0) | 5 (10.0) | 45 (90.0) | < 0.001 |

| Q9 | Having ever experienced withdrawal symptoms when stopping drugs | 38 (76.0) | 12 (24.0) | 39 (78.0) | 11 (22.0) | 1.000 |

| Q10 | Having medical problems because of drug use | 38 (76.0) | 12 (24.0) | 35 (70.0) | 15 (30.0) | 0.549 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Over half of participants (54%) reported opioid use, followed by cocaine (44%), sedatives (40%), cannabis (30%), and alcohol (32%), with volatile substances least common (20%). Methods included oral (50%), nasal (36%), and injection (38%), with 54% using multiple routes. Main reasons were curiosity/experimentation and coping with problems (74% each), peer influence (60%), and stress relief (46%), while self-medication (32%), sexual performance (20%), and shyness (20%) were less frequent (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

A significant improvement in ABS and DAST-10 scores after the rehabilitation program. High ABS scores dropped from 66% to 16%, while low scores increased from 16% to 52%. Likewise, substantial/severe DAST-10 cases decreased from 48% to 38%, and low cases rose from 6% to 24%. These changes were statistically significant (ABS: χ2 = 25.1, P < 0.001; DAST-10: χ2 = 36.14, P < 0.001). Correlation analysis revealed strong negative associations for both ABS (R = -0.554) and DAST-10 (R = -0.604), confirming reduced agitation and drug abuse severity post-intervention (Appendix 2 in Supplementary File).

After the 9-session rehabilitation program, significant improvements were observed in both behavioural and psychological outcomes. The ABS scores decreased from 96.21 ± 27.24 to 61.63 ± 27.03 (t = 10.50, P < 0.001, d = 1.10), reflecting reduced agitation. Similarly, DAST-10 scores dropped from 7.30 ± 2.30 to 3.20 ± 2.20 (t = 12.59, P < 0.001, d = 1.96), indicating a marked reduction in drug-related problems (Appendix 3 in Supplementary File).

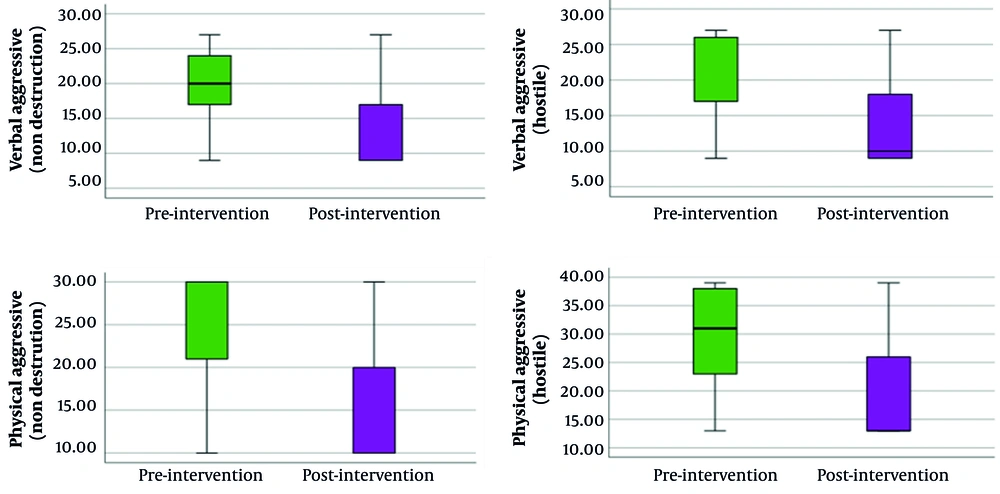

The rehabilitation program led to significant reductions across all types of aggressive behavior among patients with SUD. Verbal aggression (non-destructive) scores decreased from 20.02 ± 5.65 to 13.78 ± 6.18 (t = 10.503, P < 0.001, d = 1.165). Verbal aggressive (hostile) scores dropped from 21.30 ± 6.40 to 13.50 ± 5.86 (t = 9.505, P < 0.001, d = 1.501). Physical aggression (non-destructive) scores declined from 25.58 ± 6.53 to 14.80 ± 6.47 (t = 12.805, P < 0.001, d = 1.681). Physical aggressive (hostile) scores improved from 29.20 ± 9.09 to 19.51 ± 8.61 (t = 11.591, P < 0.001, d = 1.627; Appendix 4 in Supplementary File). Figure 1 provides a clear visualization of the intervention's impact, showing a consistent reduction in both verbal and physical aggression domains among patients with SUDs (Table 3).

| Factors | Group Comparison | Adjusted Mean (SE) | ANCOVA F (P-Value) | Partial Eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | < 36 y (n = 31) vs. ≥ 36 y (n = 19) | 2.80 (0.30) vs. 4.91 (0.45) | 0.81 (0.376) | 0.030 |

| Education | Low (n = 25) vs. high (n = 25) | 2.45 (0.32) vs. 4.82 (0.42) | 1.15 (0.294) | 0.042 |

| Marital status | Not married (n = 36) vs. married (n = 14) | 2.78 (0.28) vs. 5.68 (0.52) | 2.73 (0.110) | 0.095 |

| Start using drugs | ≤ 5 y (n = 31) vs. > 5 y (n = 19) | 3.52 (0.35) vs. 3.70 (0.44) | 0.74 (0.399) | 0.027 |

| Treatment episodes | ≤ 2 times (n = 39) vs. ≥ 3 times (n = 11) | 3.75 (0.33) vs. 3.15 (0.58) | 0.10 (0.751) | 0.004 |

| Relapses | 1 - 2 times (n = 17) vs. ≥ 3 times (n = 33) | 3.98 (0.46) vs. 3.42 (0.32) | 0.01 (0.917) | 0.000 |

| Full ANCOVA model | All factors + Baseline control (pre-intervention) | - | F(7, 42) = 2.14 (0.045) | 0.639 |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) < 2.0.

c This table presents results from ANCOVA tests for post-intervention ABS scores, controlling for the pre-intervention ABS score. The results for individual factors are from separate one-way ANCOVAs. The "Full ANCOVA model" row presents the results from a single model that includes all listed factors simultaneously.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the intervention's efficacy depended on baseline agitation severity (Appendix 5 in Supplementary File). Patients with high baseline agitation experienced a significant reduction in ABS scores, with a large effect size (mean difference: -13.0, P = 0.012, Cohen's d = 1.18). To assess clinical significance, a response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction in the ABS score. Using this criterion, 50% of the high-severity subgroup were classified as responders, compared to only 11.1% of the moderate-severity subgroup. The number needed to treat (NNT) for one additional patient to achieve this clinically meaningful response in the high-severity group was approximately 2.5. In contrast, the moderate agitation subgroup showed no significant improvement in ABS scores.

4. Discussion

This study revealed that substance use was highly prevalent among the patients, with more than three-quarters reporting cannabis, marijuana, and alcohol consumption. Over 60% of them used nasal or intravenous routes for drug administration, and more than 80% admitted to taking drugs to enhance sexual performance or to overcome shyness. Substance use was particularly common among younger, less educated, unmarried individuals — especially single or divorced — and predominantly among males, many of whom also reported symptoms of depression. Social contexts such as parties, concerts, and sporting events were common situations for smoking cannabis, as patients used substances to relieve stress and anger. These findings are consistent with regional patterns of substance use. A study by Saquib et al. on SUDs in Saudi Arabia highlighted cannabis and alcohol as the primary substances of misuse, noting that poly-drug use is a common complicating factor (10). Similarly, research by Bassiony et al. on Egyptian university students found a high prevalence of tramadol use, particularly among males (11). Furthermore, a study of an Egyptian adolescent sample identified synthetic cannabis and cocaine as the most commonly used drugs (12). Together, these regional studies corroborate the substance use patterns observed in our clinical sample.

A concerning finding in this study was that more than 80% of patients misused prescription medications without a physician's order. This misuse often led to family conflict and concerns about patients' neglect of responsibilities. The reasons for misuse included seeking euphoria, pain relief, relaxation, or assistance with sleep. These findings are consistent with Schepis et al., who reported a high lifetime prevalence of prescription drug misuse (13). Hochstatter et al. similarly documented increasing use of illicit substances (14), while Cohn and Elmasry reported early initiation of cannabis and alcohol among patients (15). Likewise, Kibet et al. highlighted family distress, social conflicts, and harmful outcomes such as deaths related to polysubstance use and nonmedical stimulant use (16).

Importantly, this study demonstrated significant improvements in patients' outcomes following completion of the rehabilitation program. Both the ABS and DAST-10 scores showed marked reductions in severity from the pre-program to post-program assessments. These promising findings are consistent with the possibility that the rehabilitation intervention may improve outcomes, including psychosocial education, behavioural counselling, and non-drug strategies. Interventions such as diaries, noise reduction, deep breathing, massage, music therapy, and progressive muscle relaxation likely contributed to reducing agitation and improving coping skills. While the significant pre-post improvements are encouraging, it is important to note that the single-group design limits our ability to rule out alternative explanations for these changes. The following discussion interprets the findings within this context. These results are consistent with Whiting et al., who confirmed that non-pharmacological interventions effectively reduce violence and aggression (17). They also align with Im et al., who reported that structured interventions provided by specialized teams significantly reduced agitation and minimized the need for restraints (18).

The use of McNemar's test and chi-square analysis provided robust evidence for the observed reductions in both aggression and substance abuse severity, confirming that the improvements were not due to chance. Furthermore, the significant negative correlations between post-intervention ABS and DAST-10 scores reinforce the effectiveness of the rehabilitation program in reducing both aggressive tendencies and substance dependence simultaneously. These findings strengthen the validity of the results and highlight the consistency across the statistical approaches used in the analysis.

Sociodemographic characteristics were also strongly associated with patients' outcomes. Younger, less educated, divorced or single, unemployed, and low-income patients exhibited higher levels of agitation and substance-related problems both before and after the rehabilitation program. These findings suggest that socioeconomic vulnerability and lack of stable social support contribute significantly to drug misuse and behavioural problems. Similar observations were reported by Menculini et al., who found higher irritability scores among younger and unemployed individuals, with married patients displaying lower agitation levels (19). Likewise, Garrote-Camara et al. noted that lower levels of education and socioeconomic status were associated with increased agitation and poorer outcomes (20).

Additionally, the study revealed a significant relationship between patients' living arrangements and their rehabilitation outcomes. Those living alone or in rural areas had persistently higher levels of agitation after rehabilitation compared with patients living with family or in urban settings. Limited access to healthcare facilities, reduced social support, cultural norms, and increased social isolation may explain these findings. Caruso et al. similarly reported that patients living alone exhibited greater physical aggression, impulsivity, and poorer adherence to treatment plans (21, 22).

While the intervention demonstrated overall effectiveness in reducing aggressive behavior and substance use severity, the impact may vary by the type of substance consumed. For instance, individuals primarily using alcohol or sedatives may experience different behavioral outcomes compared to those using marijuana, given the pharmacological and psychological effects of these substances. Although the present study was not powered to conduct detailed subgroup analyses, preliminary observations suggest that reductions in aggression were consistent across groups. Future research with larger samples is recommended to further explore substance-specific effects of rehabilitation interventions.

The subgroup analysis revealed a critical nuance: While patients with high baseline agitation responded robustly, those with moderate agitation showed no significant improvement. This finding generates the hypothesis that the intervention's focus on managing high-intensity aggression may have been a potential 'mismatch' for the needs of the moderate agitation group. For these individuals, whose primary presentation likely involves restlessness, irritability, and inner tension rather than overt aggression, the program content might have been less engaging or applicable. This suggests that this specific patient subgroup might require a different interventional approach, such as one specifically targeting underlying anxiety, restlessness, or boredom. This important hypothesis — that distinct agitation profiles require tailored interventions — should be explicitly tested in future research. Although the small size of the moderate subgroup (n = 9) means this finding must be interpreted with caution, it provides a vital direction for personalizing rehabilitation strategies.

Several non-mutually exclusive factors could explain this result for the moderate subgroup. First, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to determine if this minor increase represents a true iatrogenic effect or merely reflects random fluctuation or regression to the mean around their baseline level. The small sample size of this subgroup (n = 9) means it was severely underpowered, and the mean difference of +2.45 points is likely not clinically significant, falling well within the measurement error of the scale and far below the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for agitation scales, which often exceeds 10 - 15 points. Second, the intervention's content, which was heavily focused on anger management and coping with high-intensity aggression, may have been mismatched or less engaging for individuals whose primary issue was moderate restlessness or irritability rather than overt aggression. They might have benefited more from interventions targeting anxiety, depression, or boredom as a factor affecting (23, 24). This suggests that future iterations of rehabilitation programs should be tailored more precisely to specific agitation profiles rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

4.1. Conclusions

This study confirmed the research hypothesis by demonstrating a significant reduction in agitation behaviour scores among patients with SUD following participation in the rehabilitation program. The findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the potential value of structured rehabilitation strategies in mitigating agitation and improving behavioral outcomes. In addressing the research question, the study also identified key sociodemographic characteristics — including younger age, divorced marital status, lower educational attainment, unemployment, financial instability, and rural residence — as significant predictors of agitation severity both before and after the program. These results underscore the importance of tailoring rehabilitation interventions to individual and socio-cultural contexts, with particular focus on high-risk demographic groups. Future research is strongly recommended to: (1) Employ randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a treatment-as-usual control group to firmly establish causal efficacy; and (2) explore the adaptation and effectiveness of this rehabilitation program for more diverse populations. Key questions for implementation science include identifying the necessary cultural modifications for different groups, such as adjusting group dynamics for gender-specific settings, addressing unique stigma concerns, and incorporating relevant religious or community support structures for non-Egyptian and rural populations.

4.2. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although ANCOVA was used to control for baseline scores, the observed reductions in agitation and substance use cannot be attributed solely to the rehabilitation program with certainty. The lack of a control group poses a substantial threat to internal validity, as the improvements could be influenced by other factors such as the Hawthorne effect, maturation, historical events, or the concurrent receipt of other therapeutic services at the outpatient clinic. Second, although the analysis accounted for differences by substance type, the relatively small subgroup sizes limited statistical power to detect more nuanced effects across substance categories. Third, the short-term follow-up period (one-month post-intervention) restricted the assessment of the sustainability of treatment effects. Fourth, the generalizability of the findings is limited. The study sample consisted exclusively of Egyptian men recruited from a single clinical setting. Consequently, the results may not apply to women, individuals from other cultural or national backgrounds, or those receiving treatment in different healthcare systems. The effectiveness and cultural appropriateness of the rehabilitation program in these populations remain to be investigated. Fifth, the primary reliance on self-reported measures for key outcomes like substance use (DAST-10) and aggression, without complementary validation methods such as urine toxicology tests or collateral reports, carries a risk of reporting bias, including social desirability bias and under-reporting.