1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted global healthcare systems, necessitating swift and precise evaluations of disease severity. Critical in this assessment is oxygen saturation, a vital indicator of respiratory function, where levels below 90% suggest severe respiratory compromise (1, 2). Computed tomography (CT) scans play a crucial role in gauging the severity of COVID-19 by offering prognostic insights not captured by standard methods. The extent of lung lesions visible on CT scans correlates significantly with disease severity, providing a measurable index of lung involvement. Notably, specific radiographic patterns, such as the "crazy-paving pattern," indicate advancing severity towards substantial lung consolidation, highlighting the transition phases within the pulmonary structure affected by the infection (2-5). Non-lesion lung volume (NLLV), defined as the volume of aerated lung tissue not affected by visible lesions, provides a marker of preserved lung function. The ‘crazy-paving’ pattern refers to ground-glass opacities with superimposed interlobular septal thickening, typically associated with disease progression and increasing lung consolidation.

This evolving understanding underscores the potential of advanced machine learning (ML) models that integrate CT data with clinical and laboratory assessments to enhance the prediction accuracy of critical outcomes such as oxygen saturation. The intersection of ML and radiomics has transformed medical imaging analysis (4, 6-8). The development of sophisticated algorithms facilitates deep explorations into high-dimensional imaging data (9, 10), thus broadening the horizon for improved diagnostic precision and predictive capabilities in managing COVID-19 outcomes. However, the adoption of these advanced techniques in clinical practice is hampered by challenges such as biases in feature extraction and selection, which can undermine the reliability of predictive models (11-14). Furthermore, without careful management, feature selection processes might prioritize computational artifacts over clinically relevant data, necessitating a meticulous approach to ensure the utility of CT-integrated ML models in clinical settings.

This study models peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) measured at hospital admission — defined as the earliest recorded oxygen saturation within two hours of arrival — to anchor predictive learning on a standardized, clinically meaningful outcome. While not a substitute for direct measurement, modeling the structural determinants of initial desaturation enables retrospective triage modeling, reveals cross-modal patterns of early respiratory compromise, and provides a robust benchmark for evaluating classifier generalizability and feature relevance in real-world datasets

2. Objectives

This study aims to develop ML models that incorporate CT-based interpretable features with clinical and laboratory data to predict binary oxygen saturation outcomes in COVID-19 patients. By evaluating both linear and non-linear classifiers, this research seeks to assess their effectiveness in forecasting oxygen saturation levels, considering the evolution of CT scan features from ground-glass opacities to complete lung consolidation. We hypothesize that non-linear classifiers will outperform linear ones in CT-based and integrated models due to the complex spatial and textural patterns present in radiological data, whereas linear classifiers may suffice for clinical and laboratory variables. Incorporating domain knowledge to distinguish between clinically relevant features and computational artifacts is crucial, ensuring that the models remain applicable in real-world clinical settings, particularly regarding decisions on intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and mechanical ventilation requirements.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Population

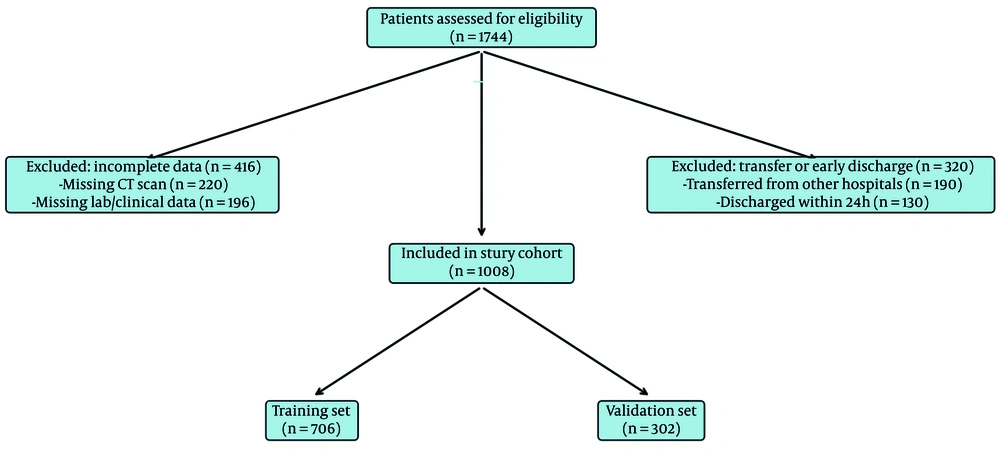

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults (≥ 18 years) with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 admitted to Baqiyatallah Hospital between October 2020 and May 2021. Inclusion required a chest CT within one day of admission; patients with incomplete clinical data or inter-hospital transfers were excluded. The primary binary outcome was peripheral oxygen saturation at first reading within two hours of admission and prior to high-flow oxygen/ventilatory support (SpO₂ < 90% vs ≥ 90%). After applying criteria, 1,008 of 1,744 patients were included (training n = 706; validation n = 302). The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1400.079); data were anonymized. A participant flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. (Details in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary File.)

Participant flow diagram. Of 1,744 patients initially assessed, 736 were excluded: 416 due to incomplete data (220 lacking CT scans; 196 missing laboratory or clinical information), and 320 due to early discharge or inter-hospital transfers (190 transferred from other hospitals; 130 discharged within 24 hours). The final study cohort consisted of 1,008 patients, split into a training set (n = 706) and a validation set (n = 302)

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Demographics, exposure history, comorbidities, symptoms, laboratory values, and treatment records were extracted from electronic health records. Continuous clinical variables were standardized using z-scores derived from the training set; categorical variables were one-hot or binary encoded. Missing data (< 10% overall) were handled via multiple imputation by chained equations. Symptom concordance with chart documentation was assessed in a validation subset. (Appendix 2 and 6 in the Supplementary File.)

3.3. Computed Tomography Acquisition, Segmentation, and Features

Non-contrast chest CT scans were acquired on a GE Revolution EVO 64-slice scanner within one day of admission using a standardized protocol. A 2D U-Net segmented lungs and lesions; outputs underwent radiologist review, with excellent agreement and high Dice coefficients. Volumetric (e.g., lesion volume; NLLV; %NLLV) and texture features were computed per image biomarker standardization initiative recommendations after intensity normalization and isotropic resampling. (Appendix 3, 4 and 5 in the Supplementary File.)

3.4. Feature Selection and Model Development

Clinical, laboratory, and CT-derived variables were considered alongside a priori covariates (age, sex, Body Mass Index, comorbidities, presenting symptoms). Classifiers included linear support vector machine (SVM), SVM with radial basis function (RBF), logistic regression, random forests (RFs), naive Bayes, and XGBoost. Feature selection used recursive feature elimination, embedded importances (RF/XGBoost), correlation/χ² tests, and minimum redundancy maximum relevance; stability analyses guided final sets (typically 8 - 22 features). Hyperparameters were tuned via Bayesian optimization with stratified cross-validation; class imbalance was addressed with synthetic minority over-sampling technique/adaptive synthetic sampling and cost-sensitive learning. (Appendix 7 and 8 in the Supplementary File)

3.5. Validation and Interpretability

We used 10-fold stratified cross-validation and an independent validation split to assess area under the curve (AUC), balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1. Feature importance was examined via model coefficients/embedded scores, permutation importance, and Shapley additive explanations for global and local effects. We used principal component analysis to visualize the distribution and separation of classes in the feature space (Appendix 9 and 10 in the Supplementary File).

3.6. Use of Artificial Intelligence Assistance

Specialized GPT-4 configurations assisted in optimization setup, literature review, and language editing, while all methodological decisions and analyses were conducted by the authors. All artificial intelligence assistance in writing, literature review, and other technical aspects was carefully checked and supervised by the authors.

4. Results

4.1. Patients’ Characteristics

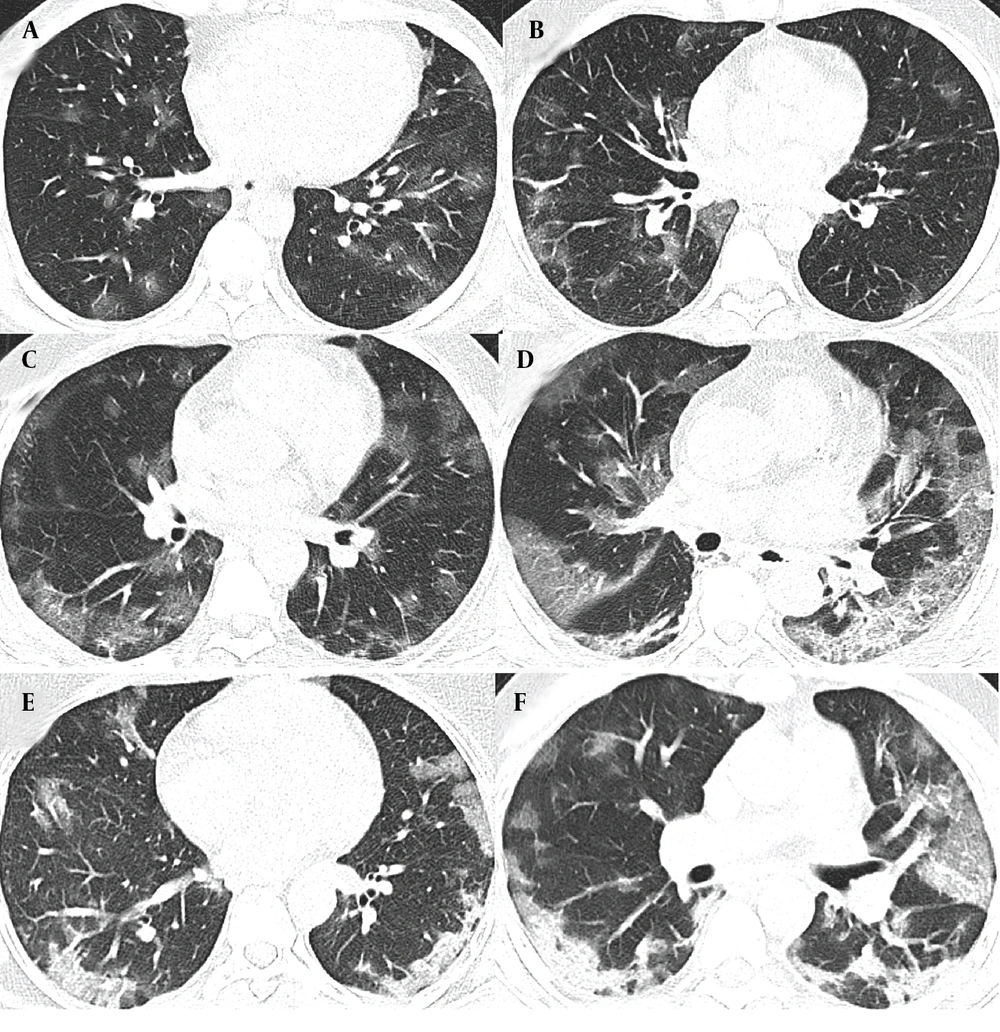

The characteristics of COVID-19 patients with oxygen saturation levels below and above 90% were examined in two distinct cohorts, each with training and validation groups. The first cohort includes patients with oxygen saturation below 90%, comprising 224 in the training group and 96 in the validation group. The second cohort involves patients with oxygen saturation equal to or above 90%, with 482 in the training group and 206 in the validation group. A detailed breakdown of clinical characteristics, biological measures, symptoms, and CT features is provided in Appendix 12, 13 and 14 in the Supplementary File. Figure 2 depicts the typical progression of lung damage in COVID-19, from ground-glass opacity to consolidation, reflecting the increasing severity of the disease. Appendix 15 in the Supplementary File provides a complete list of features selected in each model by the top-performing classifier, along with their importance and stability scores.

A and B, The radiographic progression of lung involvement in COVID-19 pneumonia, beginning with ground-glass opacity (GGO), an early radiographic finding representing alveolar damage and fluid accumulation; C, As the disease advances, GGO may increase in distribution, exhibiting peripheral predominance; C and D, The crazy paving pattern, characterized by thickened interlobular septa superimposed on ground-glass opacity, indicates deeper lung parenchyma involvement; E and F, Further progression leads to consolidation; where dense opacities obscure the underlying vasculature, signaling severe alveolar damage.

4.2. Outperformance of Linear Machine Learning Classifiers in Clinical and Laboratory Models

The performance of the ML classifiers in predicting oxygen saturation outcomes (below or above 90%) in COVID-19 patients was assessed, with the validation AUC values and training folds range detailed in Table 1, with validation AUC values and the range of AUC from 10-fold cross-validation (in parenthesis) for each model type: Clinical, Laboratory, CT-based, and Integrated. Classifiers are grouped into linear and non-linear categories. Tighter cross-validation ranges indicate greater consistency across training folds, suggesting a more reliable and generalizable model. In addition to validation AUC, we evaluated clinical utility metrics — sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value — for the best-performing classifier in each model type. The Clinical Model's logistic regression (AUC = 0.82 [95% CI: 0.80 - 0.85]) achieved a sensitivity of 0.798, specificity of 0.801, positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.776, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.823. The Laboratory Model's top classifier, linear SVM (AUC = 0.82 [95% CI: 0.80 - 0.84]), showed a sensitivity of 0.812 and specificity of 0.809, with PPV and NPV values of 0.788 and 0.832, respectively. In addition to discrimination metrics, calibration analyses were conducted for all top-performing classifiers. The Clinical Model (logistic regression) demonstrated acceptable calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ² = 6.77, df = 8, P = 0.56; Brier score = 0.118), as did the Laboratory Model (linear SVM; χ² = 7.92, P = 0.44; Brier = 0.105).

| Classifier | Clinical Model | Laboratory Model | CT-Based Model | Integrated Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear classifiers | ||||

| Logistic regression | 0.82 (0.80 - 0.85) | 0.81 (0.78 - 0.94) | 0.76 (0.78 - 0.85) | 0.84 (0.83 - 0.87) |

| Linear SVM | 0.80 (0.77 - 0.83) | 0.82 (0.80 - 0.84) | 0.71 (0.63 - 0.88) | 0.78 (0.76 - 0.90) |

| Naive Bayes | 0.76 (0.72 - 0.78) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.76) | 0.79 (0.66 - 0.82) | 0.81 (0.78 - 0.83) |

| Non-linear classifiers | ||||

| SVM (RBF Kernel) | 0.75 (0.72 - 0.78) | 0.76 (0.74 - 0.79) | 0.85 (0.86 - 0.91) | 0.89 (0.92 - 0.97) |

| RF | 0.78 (0.74 - 0.81) | 0.79 (0.76 - 0.82) | 0.87 (0.78 - 0.93) | 0.86 (0.81 - 0.96) |

| XGBoost | 0.77 (0.63 - 0.80) | 0.78 (0.71 - 0.81) | 0.81(0.77 - 0.92) | 0.85 (0.80 - 0.95) |

Abbreviation: SVM, support vector machine; RBF, radial basis function; RF, random forest.

4.3. Non-linear Classifiers Excelled in Computed Tomography-Based and Integrated Models

In the Computed Tomography-Based Model, RF (AUC = 0.87 [95% CI: 0.78 - 0.93]) achieved 0.845 sensitivity, 0.827 specificity, 0.806 positive predictive value, and 0.865 negative predictive value. The Integrated Model’s SVM with RBF kernel (AUC = 0.89 [95% CI: 0.92 - 0.97]) reached the highest overall performance, with sensitivity of 0.861, specificity of 0.824, PPV of 0.794, and NPV of 0.884.

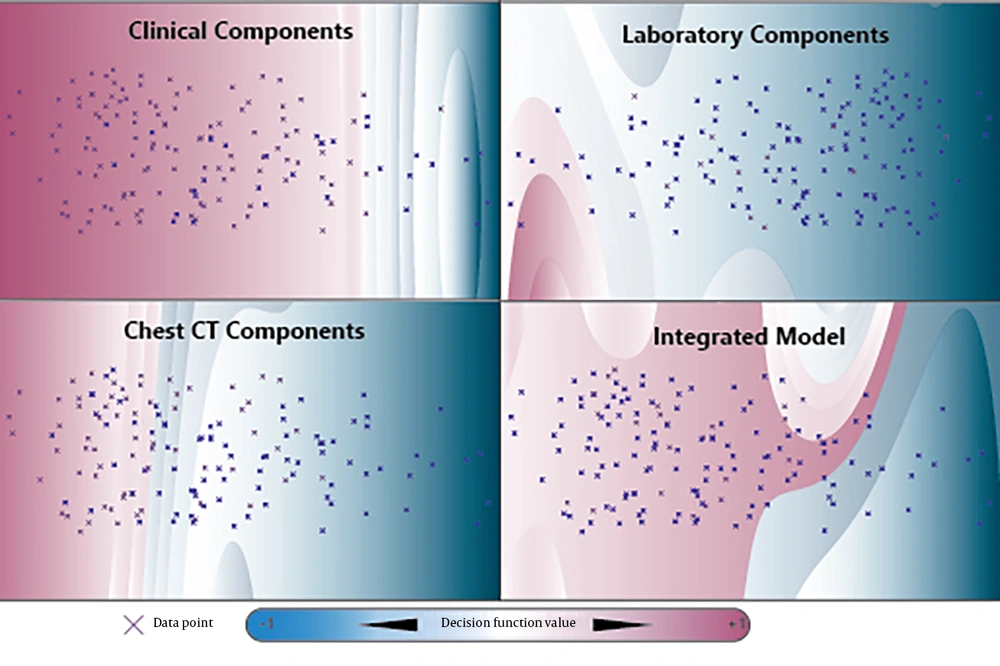

The Computed Tomography-Based Model (RF) showed strong alignment (χ² = 9.35, P = 0.31; Brier = 0.098). The Integrated Model’s SVM with RBF achieved the best calibration (χ² = 7.38, P = 0.50; Brier = 0.092), supporting the reliability of its predicted probabilities. Figure 3 illustrates the SVM with RBF decision boundaries in a two-dimensional space, derived from the first two principal components, revealing distinct patterns of separability in the clinical, laboratory, CT-based, and integrated models.

Two-Dimensional Support Vector Machine (SVM) Decision Boundaries and Heatmaps derived from Principal Component Analysis across four datasets: Clinical, laboratory, computed tomography-based (CT-based), and integrated features. The first two principal components explain a significant portion of the variance: 81.5% in the clinical dataset, 88.8% in the laboratory dataset, 71.7% in the CT-based dataset, and 79.3% in the integrated model. The SVM with radial basis function (RBF) decision boundaries in the two-dimensional space demonstrate non-linear separability patterns, particularly within the CT-based and integrated feature sets.

4.4. Key Features for Oxygen Saturation Prediction

The Clinical Model's logistic regression classifier achieved an AUC of 0.82, with age emerging as the most important predictor of oxygen saturation in COVID-19 patients (Table 2). It had a feature importance of 0.51 and a stability of 0.89. Gender followed with an importance of 0.33 and a stability of 0.81. Fever, with an importance of 0.31 and stability of 0.73, also contributed significantly, highlighting the role of clinical symptoms in oxygen saturation prediction. In the Laboratory Model, linear SVM (AUC = 0.82) identified white blood cell (WBC) count as the most significant predictor, with an importance of 0.53 and stability of 0.88. The lymphocyte count, with an importance of 0.35 and stability of 0.83, and platelet count, with an importance of 0.32 and stability of 0.80, indicate the potential link between coagulation and respiratory outcomes in COVID-19.

For the Computed Tomography-Based Model, RF achieved an AUC of 0.87, with mean lesion volume showing a high feature importance of 0.24 and stability of 0.90. Lower zone predominance achieved an importance of 0.20 and stability of 0.85, and NLLV skewness, an importance of 0.16 and stability of 0.80. In the Integrated Model, the SVM with RBF kernel (AUC = 0.89) led the way with WBC as the most significant predictor, having an importance of 0.31 and stability of 0.88. The mean NLLV followed with an importance of 0.30 and stability of 0.85, reinforcing the importance of CT-based lung volume metrics. Crazy paving, with an importance of 0.22 and stability of 0.72, highlights the role of specific CT patterns in the model's predictive accuracy. Table 2 displays the top features for predicting oxygen saturation in each model type, based on the classifier with the highest AUC in the validation dataset. The feature importance values are normalized, reflecting the relative significance of each feature within its respective model, while feature stability measures the consistency of importance across subsampling runs.

| Model Type | Best Classifier (AUC) | Top Feature 1 (Importance, Stability) | Top Feature 2 (Importance, Stability) | Top Feature 3 (Importance, Stability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical model | Logistic Regression (AUC = 0.82) | Age (0.51, 0.89) | Gender (0.33, 0.81) | Fever (0.31, 0.73) |

| Laboratory model | Linear SVM (AUC = 0.82) | WBC (0.53, 0.88) | Lymphocyte (0.35, 0.83) | Platelet Count (0.32, 0.80) |

| CT-Based model | RF (AUC = 0.87) | Mean LV (0.24, 0.90) | Lower Zone Predominance (0.20, 0.85) | NLLV skewness (0.16, 0.80) |

| Integrated model | SVMRBF (AUC = 0.89) | WBC (0.31, 0.88) | Mean NLLV (0.30, 0.85) | Crazy paving (0.22, 0.72) |

Abbreviation: AUC, Area under the curve; SVM, Support vector machine; RF, Random Forest; WBC, White blood cell; NLLV, Non-lesion lung volume; RBF, Radial basis function; LV, lesion volume.

5. Discussion

Our study explored the comparative performance of ML classifiers across four model types, focusing on the top-performing classifiers and their key features for predicting binary oxygen saturation outcomes in COVID-19 patients, to guide resource allocation in healthcare settings, such as deciding when to admit patients to ICU or administer high-flow oxygen therapy. The models incorporated a diverse set of features, including clinical, laboratory, CT-based, and integrated data to offer a comprehensive understanding of the outcomes. The best-performing classifiers for each model align with the underlying patterns of the data, reflecting the linearity or non-linearity of the feature sets. The feature importance values and stability metrics provide insights into the robustness and reliability of each model.

The ability to predict oxygen saturation levels in COVID-19 patients is crucial for assessing disease severity and guiding clinical decisions. In the Clinical Model, where the logistic regression classifier achieved an AUC of 0.82, age emerged as the most significant predictor, with a feature importance of 0.51 and a stability of 0.89. This finding underscores the well-documented correlation between advanced age and severe respiratory distress in COVID-19. Gender, with a feature importance of 0.33 and stability of 0.81, indicates possible gender-related differences in disease progression. Fever, a common symptom of COVID-19, also contributed significantly to the model, suggesting that clinical symptoms play a vital role in predicting oxygen saturation (2, 3).

The Laboratory Model, with an AUC of 0.82 for linear SVM, identified WBC count as the primary predictor. This strong importance points to the role of the immune response in the progression of COVID-19. The lymphocyte count, with an importance of 0.35 and stability of 0.83, further supports the idea that immune system markers are critical in understanding disease severity. Platelet count, with an importance of 0.32 and stability of 0.80, suggests that coagulation factors may also have a role in predicting oxygen saturation outcomes, emphasizing the broader systemic impact of COVID-19.

The Computed Tomography-Based Model, where the RF classifier achieved an AUC of 0.87, brought attention to the radiological features of COVID-19. Mean lesion volume was the top predictor, highlighting the significance of lung lesion volume in assessing disease severity. Lower zone predominance and NLLV skewness suggest that spatial distribution and volume consistency of lung tissue are essential factors in determining oxygen saturation (15). Finally, the Integrated Model, which combined clinical, laboratory, and CT-based features, demonstrated a broader range of significant predictors. The SVM with RBF kernel achieved an AUC of 0.89, with WBC count and mean NLLV as the leading predictors, suggesting that combining immune response markers with radiological data provides a more comprehensive view of disease severity. Crazy paving, a specific CT pattern, further contributes to the predictive power of the integrated approach. The integration of these diverse features emphasizes the critical role of radiology and underscores the need for ongoing research to improve predictive accuracy and clinical outcomes (2, 3, 15).

In a clinical setting, these models could be deployed as triage support tools at admission. Given that all input features are routinely available within hours, real-time prediction of oxygen saturation status could inform ICU referrals, high-flow oxygen initiation, or monitoring intensity. Probability thresholds (e.g., ≥ 0.70 from the Integrated Model) could be defined for actionable interventions, optimized to institutional capacity and risk tolerance. The model’s high NPV (NPV = 0.884) suggests that patients classified as low risk could be safely managed in general wards, aiding in resource allocation during surges. A limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which may inherently carry biases due to reliance on existing hospital records. The inclusion of only admitted patients with confirmed COVID-19 could lead to selection bias, potentially excluding milder cases not requiring hospitalization. The study's cohort focused on a single hospital, which may not represent broader demographic or regional variations. Data standardization techniques such as z-score and one-hot encoding may also introduce inconsistencies in the processed data, affecting model robustness. Finally, the CT-based features, while comprehensive, may not capture all relevant variables contributing to disease progression. The reliance on specific ML classifiers, though effective, could be restricted by their inherent assumptions and limitations, impacting the broader applicability of the findings.

Demographic imbalance — particularly in age and sex — may influence model predictions, as these variables were among the most influential features in the Clinical and Integrated models. While covariates were included to mitigate bias, subgroup-specific calibration or fairness analysis was not performed and should be addressed in future work. Institutional bias may also be present due to consistent imaging protocols and treatment pathways at a single site. Although preprocessing techniques and feature selection were designed to reduce dependency on institutional artifacts, generalizability must be confirmed through multi-center validation.

Although external validation was not performed, methodological safeguards were applied to enhance generalizability. These included stratified 10-fold cross-validation, a separate 30% test set, and robust feature selection pipelines incorporating recursive elimination, redundancy filtering, and stability subsampling. All models maintained consistent AUC performance across folds (standard deviation ≤ 0.03), and calibration metrics demonstrated reliable probability estimates. Input features were restricted to routinely available clinical, laboratory, and semantic CT variables to ensure practical transferability across settings. While external datasets remain necessary for prospective transportability testing, this study establishes internal generalization under a rigorously controlled technical design.

In conclusion, our analytical framework highlights the strengths and limitations of various classifiers across different models, emphasizing the underlying linearity or non-linearity in their feature sets. The study contributes to the field of COVID-19 research by demonstrating the importance of CT scans in assessing disease severity and predicting patient outcomes. The findings are expected to guide clinical decision-making, such as ICU admissions and the need for high-flow oxygen therapy. Additionally, the study highlights the potential of ML models to integrate various data types, leading to more accurate severity assessments and enhanced patient care.

These insights provide a detailed comparative analysis that guides the selection of the most appropriate classifiers for predicting oxygen saturation outcomes in COVID-19 patients. The intertwined and multi-level approach to the discussion underscores the importance of understanding the unique characteristics of each model type and the complex interactions among various features in determining the best-performing classifiers. The results may inform future research directions, focusing on developing quantitative analysis tools for CT scans and integrating them with clinical algorithms for improved predictive accuracy and reproducibility.