1. Background

In modern healthcare, where patient autonomy and shared decision-making are increasingly emphasized, patient-centered communication (PCC) has become a key component of effective clinical practice. The PCC promotes a collaborative, interactive model for the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients and has been a central focus of medical education in recent decades (1). Unlike the paternalistic model, which emphasizes medical expertise and positions the physician as the ultimate decision-maker, patient-centered care prioritizes respect, information sharing, and active patient involvement in consultations.

A growing body of evidence indicates that PCC improves health outcomes, patient satisfaction, and adherence to medical recommendations. Consequently, many healthcare planners consider PCC a cornerstone of high-quality care and strive to train medical staff in patient-centered practices (2). In the absence of formal training, students may adopt alternative communication models through workplace or university behavioral norms, a phenomenon often referred to as the “hidden curriculum” (3).

To evaluate current practices, researchers frequently use the Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS) to examine physicians’ and medical students’ attitudes toward the patient-physician relationship, considering factors such as age, gender, and stage of education.

International studies consistently reveal variability in patient-centered attitudes, often influenced by cultural and educational factors. Research from Europe (e.g., Greece, Sweden) and the USA generally reports doctor-centered attitudes, although females and more experienced practitioners tend to be more patient-centered (4-6). Studies from several Asian countries, including South Korea, Pakistan, and China, report even lower patient-centered tendencies (7-9). These findings indicate that male and less experienced practitioners are more likely to adopt doctor-centered approaches, highlighting the influence of both culture and experience on patient-physician communication. In many Asian and developing countries, cultural and systemic factors often favor a paternalistic, physician-centered approach.

Despite these global insights, evidence regarding Iranian medical students remains limited. Preliminary findings suggest that Iranian students show comparatively lower patient-centered attitudes, consistent with trends observed in other Asian contexts. However, compared with neighboring Middle Eastern countries such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia, where recent studies have shown a gradual shift toward more patient-centered approaches among younger practitioners, Iranian findings appear to reflect a slower transition toward patient-centeredness. Similarly, when compared with East and South Asian countries such as China and Pakistan, Iranian students demonstrate comparable or slightly higher levels of doctor-centered attitudes. These regional parallels and distinctions underscore the need to better understand contextual, cultural, and educational influences shaping communication models in Iran. Understanding these attitudes within the Iranian setting is crucial for guiding medical education strategies and promoting effective PCC locally.

In Iran, Mirzadeh et al. translated and validated the PPOS for Farsi and compared the attitudes of faculty members and medical students, reporting that faculty members had significantly lower total scores and were more doctor-centered (10). Similarly, Rohani et al. assessed medical interns’ attitudes at the beginning and end of their internship at Kerman University of Medical Sciences, finding improvement in the caring subscale but not in the sharing subscale (11).

2. Objectives

This study represents the first cross-sectional analysis of Iranian medical students’ attitudes toward PCC. It aims to assess patient-centered attitudes across different stages of medical education and examine their associations with demographic factors such as age and gender.

3. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences in 2018 - 2019 to evaluate medical students’ attitudes toward the doctor-patient relationship across different stages of medical education. Medical education in Iran comprises four stages: Basic sciences (five semesters of theoretical courses), semiology and physiopathology (two semesters), externship (approximately 20 months of clinical rotations), and internship (around 18 months of direct patient care). Students were stratified according to these stages because each represents a distinct level of clinical exposure, which may influence patient-centered attitudes.

We used a questionnaire consisting of two parts. The first part collected socio-demographic information, including gender, age, and stage of education. The second part was the PPOS, which has been validated in several studies (9) and is the most commonly used tool to evaluate students’ attitudes toward PCC (12). The PPOS contains 18 items in two subscales: “Sharing” (physicians’ beliefs in equitable distribution of power, control, and information) and “caring” (attention to patients’ lifestyles, emotions, and expectations). Items are scored from 1 (strongly doctor-centered) to 6 (strongly patient-centered); mean scores ≥ 5 indicate patient-centered attitudes, while scores < 4.57 indicate doctor-centered attitudes (4). The Farsi version of PPOS has demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.8) (10); in our study, reliability was 0.70.

Participants were selected using a multistage sampling method. Within each educational stage, three classes were randomly selected, and all students in those classes were invited to participate. Sample size was calculated using the following formula: Z2 × SD2/d2. Assuming SD = 0.95, 99% confidence (Z = 2.576), precision = 5%, a 20% nonresponse rate, and a design effect of 2, the final sample size was 402 participants.

Inclusion criteria consisted of students who had completed at least six months in their current educational stage. This timeframe ensured sufficient exposure to the learning environment and clinical experiences relevant to that stage, allowing a more accurate assessment of attitudes toward patient-centered care. This criterion was applied uniformly across all four stages. Incomplete questionnaires were excluded. Questionnaires were distributed after providing instructions and obtaining informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC.1392.126).

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test for two groups and one-way ANOVA for more than two groups. Spearman correlation was used to assess the relationship between age and PPOS scores. Linear regression models were constructed for the total PPOS score as well as the ‘sharing’ and ‘caring’ subscales. Independent variables included sex and stage of education, selected based on prior literature and the study hypothesis that demographic factors may influence patient-centered attitudes. A type I error rate of 1% (α = 0.01) was applied to reduce the risk of false-positive findings due to multiple comparisons and to ensure the robustness of the results. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.01.

4. Results

A total of 402 questionnaires were distributed among medical students, of which 363 valid questionnaires were returned. The overall response rate was 90%. Table 1 shows the students’ demographic data. The mean age of the respondents was 22.92 ± 1.60, and more than half of the students were female (51%).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 168 (48.97) |

| Female | 175 (51.03) |

| Stage of education | |

| Internship | 95 (26.17) |

| Externship | 94 (25.89) |

| Basic sciences | 85 (23.42) |

| Physiopathology | 89 (24.52) |

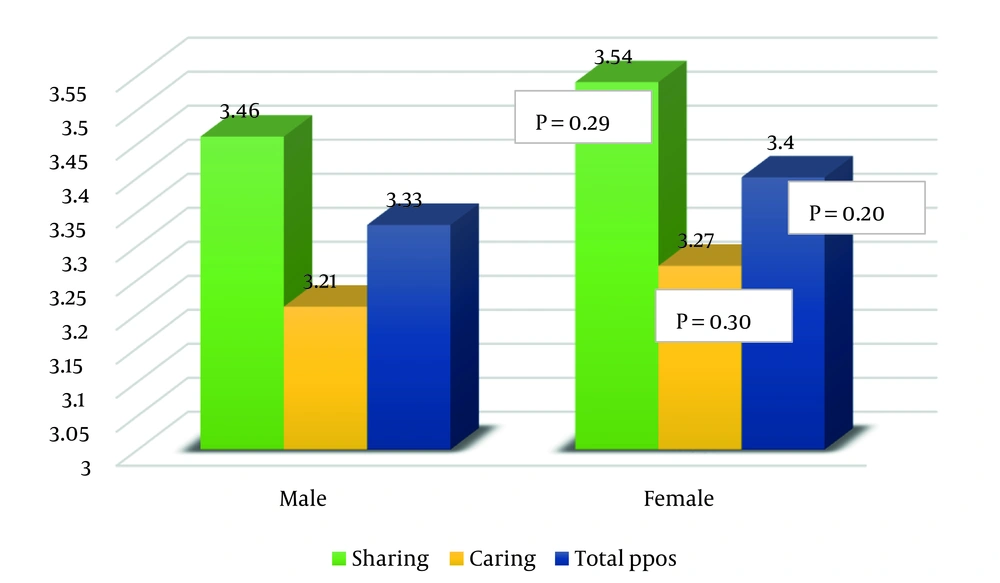

The majority of participants in our study had doctor-centered attitudes. The mean score for overall PPOS was 3.36 ± 0.38, and the mean scores for the sharing and caring domains were 3.53 ± 0.56 and 3.26 ± 0.39, respectively. Table 2 presents the mean sharing, caring, and total PPOS scores along with the results of the comparison of means. Female students displayed a higher total PPOS score in comparison with male students (Figure 1), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.20). The Spearman correlation coefficient showed a negative correlation between age and sharing score (P = 0.007), meaning older students were less patient-centered in the sharing subscale.

| Variables | Sharing | Caring | Total PPOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3.46 ± 0. 6 | 3.21 ± 0. 49 | 3.33 ± 0. 61 |

| Female | 3.54 ± 0.54 | 3.27 ± 0. 32 | 3.40 ± 0.62 |

| P b | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| Stage of education | |||

| Internship | 3.46 ± 0.60 | 3.21 ± 0.40 | 3.33 ± 0.40 |

| Externship | 3.43 ± 0.55 | 3.27 ± 0.38 | 3.36 ± 0.34 |

| Basic sciences | 3.58 ± 0.51 | 3.25 ± 0.41 | 3.39 ± 0.39 |

| Physiopathology | 3.65 ± 0.55 | 3.29 ± 0.39 | 3.45 ± 0.40 |

| P c | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.50 |

Abbreviation: PPOS, Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Independent samples t-test.

c One-way ANOVA test.

Sharing scores were independently correlated with externship and internship stages in linear regression analysis (Table 3), but there was no correlation between students’ gender and sharing scores (P = 0.28). Likewise, caring scores showed no significant relationships with demographic variables or stage of education.

| Variables | Sharing | Caring | Total PPOS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | P | Estimate | SE | P | Estimate | SE | P | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.33 | -0.24 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| Stage of education | |||||||||

| Internship | -0.30 | 0.12 | 0.01 | -0.08 | 0.08 | 0.32 | -0.37 | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| Externship | -0.21 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.96 | -0.20 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| Basic sciences | -0.21 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.99 | -0.51 | 0.66 | 0.44 |

| Physio-pathology | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; PPOS, Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale; R2, regression coefficient.

In order to evaluate the impact of missing demographic data, we used multiple imputation (MI) analysis. The MI helps to take into account uncertainty in predicting missing values by making multiple complete datasets. The MI analysis revealed no significant impact by the missing values on our final results (Table 4).

| Characteristics | Sharing | Caring | Total PPOS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | P | Estimate | SE | P | Estimate | SE | P | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.35 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.55 | -0.12 | 0.14 | 0.38 |

| Stage of education | |||||||||

| Internship | -0.31 | 0.12 | 0.009 | -0.12 | 0.08 | 0.15 | -0.28 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| Externship | -0.21 | 0.09 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.65 | -0.24 | 0.12 | 0.004 |

| Basic sciences | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.76 | -0.002 | 0.19 | 0.07 | -0.12 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| Physio-pathology | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||||||

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; PPOS, Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale; R2, regression coefficient.

5. Discussion

This study explored how medical students at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences view communication and decision-making with patients. Most students showed doctor-centered attitudes, especially in clinical years, with younger and female students slightly more patient-centered. Compared to students in the USA and some European countries, Iranian students’ scores were lower, but similar to those in Pakistan, Nepal, and Nigeria. Cultural norms, hierarchical medical education, and exposure to clinical environments appear to reduce empathy and shared decision-making. These findings suggest the need for targeted training in PCC to prepare future doctors for more collaborative care.

Understanding medical students’ patient-centered attitudes helps identify gaps in communication training and guides curriculum development toward fostering empathy and shared decision-making. Incorporating formal PCC training early in medical education can promote more patient-centered clinical behaviors and improve doctor–patient relationships. The findings highlight the need for culturally adapted educational interventions to strengthen PCC within Iranian and regional medical contexts.

The data obtained from medical students at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences showed that the majority of participants had doctor-centered attitudes. The mean score for the overall PPOS was 3.21 ± 1.25. Female students had a higher total PPOS score. Sharing and total PPOS scores were independently correlated with externship and internship stages, and there was a negative correlation between age and sharing score, meaning older students were less patient-centered in the sharing subscale.

The findings revealed that the mean total PPOS score, as well as sharing and caring scores, are lower than those reported in past studies in the USA, Vietnam, and Korea (4, 8, 13, 14) and are closer to those from Nepal, Pakistan, and Nigeria (7, 15, 16). This is consistent with previous findings that suggest the social norms and culture in Asian and developing countries lead physicians towards a paternalistic, physician-centered view in patient-physician relationships (17). The emphasis on traditional medicine, which espouses unequal power between the doctor and the patient, provides a superior position for physicians and generates a doctor-knows-best attitude toward the provider-patient relationship (18). Additionally, since many patients in these countries do not have sufficient education and access to medical information, only younger and more educated people question their doctor’s decisions, while others often accept instructions without questioning or participating in the treatment process.

The findings also provide support for the distress hypothesis (19) since reduced quality of life, changes in living conditions, and absence of a calm environment are among major external stressors for healthcare providers in Middle Eastern countries. This finding is also supported by Bauer in a neurophysiological study in Germany, showing that anxiety, tension, and stress can significantly reduce the signaling rate of mirror neurons, which in turn reduces the ability to empathize, understand others, and perceive subtleties (20).

In our study, the mean total score and sharing and caring scores were higher in female students, but this correlation was not statistically significant. This is contrary to most previous studies, which suggest a more patient-centered perspective in female students and physicians (4, 6, 8, 13). However, this observation is consistent with the results of studies in Pakistan and Nepal (7, 15), indicating the importance of social and cultural norms in the doctor-patient relationship (12). One explanation is the tendency of women to adapt to the dominant doctor-centered culture in their society, especially in their later academic years, an issue which was investigated in a study by Batenburg et al. in the Netherlands (21).

In terms of age, we found that as students get older, there is a decline in patient-centered attitudes. Similar findings have been reported in the USA and Iran, where senior students demonstrated lower empathy and patient-centeredness scores compared to junior students (4, 10). Previous systematic reviews and longitudinal studies also support the notion that patient-centered orientations tend to decline during the clinical years, although sometimes with small to moderate effect sizes (22, 23). This decline may be explained by the process of professional identity formation and exposure to the hidden curriculum, in which hierarchical role modeling and increased reliance on one’s clinical expertise reduce attention to patient participation (21, 24). Moreover, heavy clinical workload and cognitive demands may downregulate empathic responses and contribute to a more doctor-centered orientation (25). These mechanisms collectively provide a theoretical grounding for the negative association we observed between age and the sharing subscale in our sample.

Similar to studies performed in Brazil (26), in our study, the caring subscale did not show significant changes at different stages of education, while the sharing score increased in the first two stages (basic sciences and physiopathology) but decreased during externship and internship; this decline was marginally significant between the physiopathology and externship stages. This result is contrary to studies conducted in Pakistan and Sweden (6, 7) and is more similar to the study in the USA, in which patient-centered care was associated with the first years of medical education (4).

The decrease in scores, especially at a time when students start clinical work at hospitals, highlights the importance of the effect of the “hidden” or “informal curriculum” as described by Hafferty. The hidden curriculum is a set of environmental and cultural structures in the community or at work that affect students during their education. As students are exposed to the clinical environment, they learn the common behaviors of professors and senior students, which may be contrary to what is taught in the formal curriculum (3).

In addition, the structure of the formal curriculum itself may contribute to this pattern. In Iran, as in many countries, medical education strongly emphasizes biomedical knowledge and clinical management, while less attention is given to communication skills, shared decision-making, and patient-centered care. Moreover, the hierarchical institutional culture in teaching hospitals, where students often model the behavior of senior physicians, reinforces doctor-centered attitudes and limits opportunities to practice PCC (27).

Another explanation for this phenomenon has been proposed by ER Werner as “the vulnerability of the medical student”. When medical students enter a clinical environment and encounter mortality and morbidity distress for the first time, they may try to dehumanize patients as a defensive reaction. Thus, they become less empathic in their attitude towards patients (28). This is also in line with previous neurological studies in healthcare professionals that demonstrate downregulation of sensory processes in response to the perception of pain in others (29).

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences regarding changes across educational stages; longitudinal studies would provide stronger evidence. Second, as the data were collected from a single institution, the generalizability of findings may be restricted despite the use of a nationally mandated curriculum. Future studies incorporating multiple institutions or cross-country comparisons would provide a more comprehensive understanding of medical students’ patient-centered attitudes and strengthen the generalizability of the findings. Third, reliance on self-reported questionnaires may have introduced recall or social desirability bias, and unmeasured factors such as personality traits or prior clinical exposure could have acted as confounders. Finally, the exclusive use of the PPOS is another limitation, as it measures attitudinal orientation but not actual behavior. Future research should therefore combine PPOS with other validated instruments (e.g., JSE, CSAS) and observational or qualitative methods to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of medical students’ patient-centered attitudes.

5.1. Conclusions

Our results suggest that the current curriculum does not meet the requirements of a patient-centered system, and the shift in students’ scores in their first year of clinical work supports the idea that students are more affected by the hidden curriculum in their workplace than by what is taught through their formal education. Based on the results of this study, in order to achieve the standards of modern medicine and train physicians who can take a comprehensive approach to treatment, medical universities in Iran should include systematic training and communication skills in their educational programs, especially in the early months of students’ exposure to the clinical environment. Educating medical students on the appropriate handling of distress in the workplace and informing them about the effects and consequences of the hidden curriculum is another strategy for promoting patient-centeredness. Additional multicenter studies are needed to detail the changes in physicians’ attitudes over the course of their medical training and to develop systematic assessment and training programs.

5.2. Highlights

• Understanding medical students’ patient-centered attitudes helps identify gaps in communication training and guides curriculum development toward fostering empathy and shared decision-making.

• Incorporating formal PCC training early in medical education can promote more patient-centered clinical behaviors and improve doctor–patient relationships.

• The findings highlight the need for culturally adapted educational interventions to strengthen patient-centered communication within Iranian and regional medical contexts.

5.3. Lay Summary

This study explored how medical students at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences view communication and decision-making with patients. Most students showed doctor-centered attitudes, especially in clinical years, with younger and female students slightly more patient-centered. Compared to students in the USA and some European countries, Iranian students’ scores were lower, but similar to those in Pakistan, Nepal, and Nigeria. Cultural norms, hierarchical medical education, and exposure to clinical environments appear to reduce empathy and shared decision-making. These findings suggest the need for targeted training in patient-centered communication to prepare future doctors for more collaborative care.