1. Background

On the threshold of the third decade of the 21st century, we are witnessing an unprecedented digital revolution in the healthcare field that has transformed the traditional foundations of medical diagnosis, treatment, and education (1). Artificial intelligence (AI), as a manifestation of this massive transformation, is not only considered a tool for optimizing processes but also draws a new paradigm in the methods of healthcare service delivery and health professional training (2).

The nursing profession, with over 28 million individuals worldwide, constitutes the largest healthcare workforce (3). The AI offers transformative capacities in nursing education that extend beyond the traditional concept of teaching aids. From personalizing learning paths and advanced clinical simulations to intelligent processing of patient information and predicting treatment outcomes, these technologies provide a boundless space of possibilities for improving the quality of education (4).

Scientific evidence indicates that a lack of sufficient knowledge about AI can culminate in anxiety and concern among students, even impacting their professional career choices (5). Additionally, according to studies, AI purposeful implementation can enhance students’ clinical self-confidence by 23%, reduce the time to access medical knowledge by 67%, and improve the accuracy of clinical decision-making by 18%. These findings highlight the transformative potential of AI in creating a new generation of capable nurses who are prepared to face the complexities of modern healthcare (6).

Despite its high potential, AI implementation in nursing education is accompanied by considerable challenges and concerns (7). Extensive studies have reported deep concerns about patient privacy (65.6%), the possibility of incorrect conclusions (68.8%), and medico-legal consequences (68.6%). These issues have led to 67.8% of nursing researchers being hesitant to use AI tools in healthcare decision-making (8, 9). Therefore, reputable international organizations emphasize that healthcare professionals should also be familiar with the principles, ethical considerations, data protection, and critical analysis of AI (10, 11).

As the architects of the future of this vital profession, nursing faculty members bear significant responsibilities for preparing the next generation of nurses to practice in complex, AI-driven clinical settings (12). However, while 82.5% of nursing faculty members have at least a basic familiarity with AI tools, only 44% express a medium level of knowledge, and 65% show positive attitudes toward these technologies (13). Recent systematic reviews indicate that AI-related digital literacy among healthcare professionals is significantly suboptimal, with 40% of studies reporting insufficient levels of preparedness (14). This situation, while 91.11% of experts believe in the positive potential of AI, highlights a deep contradiction between existing expectations and preparedness. This gap underscores the necessity for comprehensive and multidimensional research to gain a deeper understanding of the various aspects of this complex phenomenon (15). Given the existing gaps in the literature and the need for a deeper understanding of the perspectives of nursing faculty members, as well as their critical role in developing and applying new technologies, investigating professors’ knowledge, attitudes, and performance regarding AI can be effective in identifying barriers and preparing the ground for the effective implementation of these technologies in education and healthcare (16).

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted aiming at a comprehensive investigation into the knowledge, attitudes, application, benefits, and concerns of professors regarding AI at the School of Nursing, Abadan University of Medical Sciences, in 2024 - 2025.

3. Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted during the academic year 2024 - 2025 on 71 professors at the School of Nursing, Abadan University of Medical Sciences. For the appropriate sample size selection, the professors were enrolled in the study by a census method. The inclusion criterion for professors was teaching at the School of Nursing with a minimum of one year of work experience. The exclusion criterion was incomplete questionnaires in the form of more than 5% of missing data in all questionnaire items.

For data collection, the researcher obtained the necessary permissions from Abadan University of Medical Sciences and proceeded to the School of Nursing to sample professors. The sampling was carried out among the nursing professors. The participants were first provided with the necessary explanations regarding the research objectives, the confidentiality of their information, the research methodology, and how to access the study results. Subsequently, the link to the electronic questionnaire, which was designed on the DigiSurvey platform, was sent to the professors’ phone numbers via messaging applications, such as Eitaa and WhatsApp. The participants would click the provided link to first complete the informed consent form and then the questionnaire.

The data were collected using the questionnaire from Hamedani et al.’s study (17). The first part of the questionnaire included demographic information, and the second part comprised 13 questions assessing nurses’ attitudes toward the use of AI. These questions were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), with each item valued between one and five. A score of 13 - 35 denotes an unfavorable attitude toward the use of AI, a score of 36 - 50 indicates a relatively favorable attitude, and a score of 51 - 65 shows a favorable attitude. The third part, consisting of 12 questions to examine the applications of medical AI from the perspective of nurses, was scored on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: Very high (5 points), high (4 points), low (3 points), very low (2 points), and AI should not be used in this field (1 point). A score of 12 - 32.5 indicates low use of AI, a score of 32.6 - 46 denotes moderate use of AI, and a score of 47 - 60 shows high use of AI. The fourth part of the questionnaire consisted of eight questions assessing nurses’ knowledge of AI, using a 3-point Likert scale as follows: Yes, it is correct (3 points), No, it is not correct (2 points), and I do not know (1 point). A score of 8 - 13.5 denotes low knowledge, a score of 13.6 - 19 indicates moderate knowledge, and a score of 20 - 24 shows high knowledge. The benefits and concerns regarding AI were also evaluated through 21 questions. The content validity of the questionnaire was confirmed by expert opinions, and the reliability of its dimensions was established using internal consistency and a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.81 (17).

Following data collection, the data were analyzed using SPSS software version 27. For the descriptive findings, central tendency indices [mean ± standard deviation (SD)], frequency, and percentage were used. For the inferential analysis of the data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), independent samples t-test, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were utilized.

4. Results

A total of 71 nursing professors (mean age = 35.97 ± 7.62 years) from Abadan University of Medical Sciences were investigated in this study. The majority of participants were female (71%). Analysis of the participants’ AI technology usage patterns revealed that 77.4% of the professors had prior experience using AI, 51.6% had participated in at least one AI-related workshop, and only 29% had taken a formal AI-related course. Among the various types of AI tools, ChatGPT was the most frequently used (74.2%) and Qwen was the least frequently used AI tool (3.2%). Table 1 presents the frequency and percentage of various types of AI tools used by the professors.

| AI | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| The use of AI | |

| Yes | 55 (77.4) |

| No | 16 (22.6) |

| Participation in AI workshops | |

| Yes | 37 (51.6) |

| No | 34 (48.4) |

| Participation in AI educational courses | |

| Yes | 21 (29.0) |

| No | 50 (71.0) |

| Chat GPT | |

| Yes | 53 (74.2) |

| No | 18 (25.8) |

| Gemini | |

| Yes | 21 (29.0) |

| No | 50 (71.0) |

| Copilot | |

| Yes | 5 (6.5) |

| No | 66 (93.5) |

| Perplexity | |

| Yes | 5 (6.5) |

| No | 66 (93.5) |

| DeepSeek | |

| Yes | 25 (35.5) |

| No | 46 (64.5) |

| Claude | |

| Yes | 7 (9.7) |

| No | 64 (90.3) |

| Qwen | |

| Yes | 2 (3.2) |

| No | 69 (96.8) |

| Grok3 | |

| Yes | 9 (12.9) |

| No | 62 (87.1) |

| Total | 71 (100) |

Abbreviation: AI, artificial intelligence.

The results demonstrated that the mean score for knowledge of AI was 16.77 ± 4.43, being at a moderate level. Professors’ attitudes toward AI were 39.83 ± 11.85, also being at a moderate level. The mean score for the application of AI was reported as 20.70 ± 7.12, indicating low use of AI. Additionally, understanding the benefits of AI yielded a mean score of 18.12 ± 3.27, and professors’ concerns about AI were reported as 9.03 ± 1.66, being at low and moderate levels, respectively. These findings are presented in Table 2.

| Variables | Score Range | Lowest - Highest Score | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 8 - 24 | 8 - 23 | 16.77 ± 4.43 |

| Attitudes | 13 - 65 | 16 - 53 | 39.83 ± 11.85 |

| Application | 12 - 60 | 12 - 44 | 20.70 ± 7.12 |

| Benefits | 15 - 30 | 15 - 29 | 18.12 ± 3.27 |

| Concerns | 6 - 12 | 6 - 12 | 9.03 ± 1.66 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

In a survey of professors’ perspectives on the benefits of AI, the highest levels of agreement belonged to increased speed of service delivery (97.2%), access to vast patient databases (93.0%), and AI’s lack of time and location constraints (90.1%). In contrast, the lowest level of agreement was observed in reliance on AI in difficult decision-making (35.2%). Regarding concerns, the most significant concerns reported by professors were the potential for disclosure of confidential patient information (84.5%) and inability to empathize with patients (64.8%). In contrast, concerns about the diminished role of medical team members (45.1%) and increased workload (9.9%) were reported less frequently. These findings indicate that professors generally perceive AI as beneficial, but concerns about privacy and the human aspects of care must be addressed. Table 3 illustrates these findings.

| Variables; Items | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Benefits | |

| The AI reduces healthcare costs. | |

| Agree | 62 (87.3) |

| Disagree | 9 (12.7) |

| The AI reduces the duration of patient hospital stay. | |

| Agree | 60 (84.5) |

| Disagree | 11 (15.5) |

| The AI increases the speed of service delivery to clients. | |

| Agree | 69 (97.2) |

| Disagree | 2 (2.8) |

| The AI can eliminate many current medical weaknesses. | |

| Agree | 55 (77.5) |

| Disagree | 16 (22.5) |

| The AI can reduce the heavy workload of medical team members. | |

| Agree | 53 (74.6) |

| Disagree | 18 (25.4) |

| The AI creates new jobs in the healthcare field. | |

| Agree | 53 (74.6) |

| Disagree | 18 (25.4) |

| The AI has no physical limitations or fatigue. | |

| Agree | 62 (87.3) |

| Disagree | 9 (12.7) |

| The AI is not constrained by time or location. | |

| Agree | 64 (90.1) |

| Disagree | 7 (9.9) |

| The AI can help reduce medical errors. | |

| Agree | 62 (87.3) |

| Disagree | 9 (12.7) |

| The AI can reduce differences in judgments and diagnoses among physicians. | |

| Agree | 57 (80.3) |

| Disagree | 14 (19.7) |

| The AI opinions can be relied upon in making difficult decisions. | |

| Agree | 25 (35.2) |

| Disagree | 46 (64.8) |

| By using AI, doctors will have more time for their patients and also for focusing on more complex tasks. | |

| Agree | 55 (77.5) |

| Disagree | 16 (22.5) |

| The AI systems provide reliable reports after analyzing patient data. | |

| Agree | 41 (57.7) |

| Disagree | 30 (42.3) |

| The AI grants researchers access to a massive database of anonymized patients from across the country. | |

| Agree | 66 (93.0) |

| Disagree | 5 (7.0) |

| The use of AI increases profitability for medical centers. | |

| Agree | 60 (84.5) |

| Disagree | 11 (15.5) |

| Concerns | |

| There is a potential for the disclosure of patient confidential information by certain individuals or hackers. | |

| Agree | 60 (84.5) |

| Disagree | 11 (15.5) |

| The AI increases the workload of treatment team members. | |

| Agree | 7 (9.9) |

| Disagree | 64 (90.1) |

| The AI lacks the ability to empathize patients and consider their emotional behavior. | |

| Agree | 46 (64.8) |

| Disagree | 25 (35.2) |

| The AI can harm the physician-patient relationship. | |

| Agree | 39 (54.9) |

| Disagree | 32 (45.1) |

| The AI reduces the number of medical team members needed in the community. | |

| Agree | 34 (47.9) |

| Disagree | 37 (52.1) |

| The AI diminishs the role of medical team members in treating patients in the future. | |

| Agree | 32 (45.1) |

| Disagree | 39 (54.9) |

Abbreviation: AI, artificial intelligence.

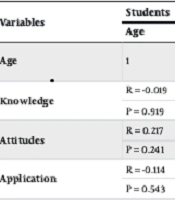

The results of Pearson’s correlation test revealed that age has a significant negative correlation with both knowledge (R = -0.119, P = 0.031) and attitude (R = -0.217, P = 0.024). This indicates that an increase in age is associated with a decrease in both knowledge and attitude. However, age had no significant correlation with application, benefits, or concerns (P > 0.05). Additionally, knowledge was positively correlated with attitude (R = 0.611, P < 0.001), application (R = 0.651, P < 0.001), and benefits (R = 0.475, P = 0.007), meaning that higher levels of knowledge were associated with more positive attitudes, greater application, and higher reported understanding of benefits. Moreover, attitude showed a positive correlation with application (R = 0.550, P = 0.001) and benefits (R = 0.564, P = 0.001). The strongest correlation was found between application and benefits (R = 0.654, P < 0.001). In contrast, concerns had no significant correlation with any of the variables (P > 0.05). These findings underscore that enhancing professors’ knowledge can culminate in more positive attitudes, increased application, and a better understanding of the benefits of AI. Meanwhile, concerns operate more independently of these variables and are likely dependent on other factors. Pearson’s correlation coefficients are reported in Table 4.

| Variables | Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Knowledge | Attitudes | Application | Benefits | Concerns | |

| Age | 1 | R = -0.119 | R = -0.217 | R = -0.114 | R = 0.044 | R = 0.084 |

| P = 0.031 | P = 0.024 | P = 0.061 | P = 0.813 | P = 0.652 | ||

| Knowledge | R = -0.019 | 1 | R = 0.611 | R = 0.651 | R = 0.475 | R = -0.049 |

| P = 0.919 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.007 | P = 0.795 | ||

| Attitudes | R = 0.217 | R = 0.611 | 1 | R = 0.550 | R = 0.564 | R = -0.094 |

| P = 0.241 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.613 | ||

| Application | R = -0.114 | R = 0.651 | R = 0.550 | 1 | R = 0.654 | R = -0.120 |

| P = 0.543 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.520 | ||

| Benefits | R = 0.044 | R = 0.475 | R = 0.564 | R = 0.654 | 1 | R = -0.307 |

| P = 0.813 | P = 0.007 | P = 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.093 | ||

| Concerns | R = 0.084 | R = -0.049 | R = -0.094 | R = -0.120 | R = -0.307 | 1 |

| P = 0.652 | P = 0.795 | P = 0.613 | P = 0.520 | P = 0.093 | ||

Univariate analysis revealed that gender had no statistically significant correlation with any of the domains of knowledge, attitudes, application, benefits, and concerns regarding AI (P > 0.05). However, the mean score for concerns was higher for males than for females (9.88 ± 1.05 versus 8.68 ± 1.75; P = 0.066). Moreover, overall use of AI did not create any significant differences in the domains, although individuals who did not use AI had higher concerns (P = 0.080). In contrast, the use of some specific AI tools accompanied significant changes; in particular, DeepSeek users reported a lower level of knowledge (P = 0.005), less frequent application (P = 0.001), and a more limited understanding of benefits (P = 0.023), and the use of Grok3 was also associated with lower knowledge (P = 0.036). Additionally, taking AI training courses was associated with more positive attitudes (P = 0.037), and participating in educational workshops was associated with reduced concerns (P = 0.038). Other AI tools, as well as variables like work experience and academic rank, did not show any significant differences (P > 0.05). The results of the univariate analysis among the investigated variables are reported in Table 5.

| Variables | Knowledge | Attitudes | Application | Benefits | Concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | |

| Gender | 0.868 | 0.803 | 0.611 | 0.985 | 0.066 | |||||

| Male | 16.55 ± 4.82 | 29.44 ± 5.60 | 19.66 ± 6.91 | 18.11 ± 2.42 | 9.88 ± 1.05 | |||||

| Female | 16.86 ± 4.37 | 30.00 ± 5.89 | 21.13 ± 7.33 | 18.13 ± 7.33 | 8.68± 1.75 | |||||

| The use of AI | 0.597 | 0.811 | 0.442 | 0.374 | < 0.080 | |||||

| Yes | 16.54 ± 4.34 | 29.70 ± 5.15 | 20.16 ± 7.52 | 18.41 ± 3.48 | 8.75 ± 1.72 | |||||

| No | 17.57 ± 4.99 | 30.28 ± 6.94 | 22.57 ± 5.65 | 17.14 ± 2.34 | 10.00 ± 1.00 | |||||

| Chat GPT | 0.773 | 0.477 | 0.808 | 0.264 | 0.365 | |||||

| Yes | 16.91 ± 4.03 | 30.26 ± 4.48 | 20.52 ± 7.48 | 18.52 ± 3.52 | 8.86± 1.65 | |||||

| No | 16.37 ± 5.73 | 28.62 ± 7.96 | 21.25 ± 6.43 | 17.00 ± 2.20 | 9.50 ± 1.69 | |||||

| Gemini | 0.074 | 0.599 | 0.146 | 0.709 | 0.137 | |||||

| Yes | 14.55 ± 4.36 | 30.66 ± 6.44 | 17.77 ± 6.53 | 17.77 ± 2.81 | 8.33 ± 1.50 | |||||

| No | 17.68 ± 4.22 | 29.50 ± 5.17 | 21.90 ± 7.15 | 18.27 ± 3.49 | 9.31 ± 1.67 | |||||

| Copilot | 0.930 | 0.458 | 0.343 | 0.247 | 0.404 | |||||

| Yes | 16.50 ± 4.94 | 27.00 ± 0.00 | 16.00 ± 2.82 | 15.50 ± 0.70 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | |||||

| No | 16.79 ± 4.49 | 30.03 ± 5.62 | 21.03 ± 7.24 | 18.31 ± 3.30 | 8.96 ± 1.70 | |||||

| Perplexity | 0.463 | 0.827 | 0.456 | 0.476 | 0.202 | |||||

| Yes | 14.50 ± 2.12 | 29.00 ± 822 | 17.00 ± 4.24 | 16.50 ± 0.70 | 10.50 ± 0.70 | |||||

| No | 16.93 ± 4.52 | 29.89 ± 5.64 | 20.96 ± 7.26 | 18.24 ± 3.35 | 8.93 ± 1.66 | |||||

| Deepseek | 0.005 | 0.170 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.717 | |||||

| Yes | 13.90 ± 4.10 | 28.00 ± 4.85 | 15.54 ± 3.53 | 16.36 ± 1.56 | 9.18 ± 1.60 | |||||

| No | 18.35 ± 3.84 | 30.85 ± 5.65 | 23.55 ± 7.05 | 19.10 ± 3.58 | 8.95 ± 1.73 | |||||

| Claude | 0.091 | 0.870 | 0.104 | 0.174 | 0.696 | |||||

| Yes | 12.66 ± 3.51 | 29.33 ± 3.21 | 14.33 ± 0.57 | 15.66 ± 0.57 | 8.66 ± 1.52 | |||||

| No | 17.21 ± 4.34 | 29.89 ± 5.71 | 21.39 ± 7.17 | 18.39 ± 3.33 | 9.07 ± 1.69 | |||||

| Qwen | 0.074 | 0.567 | 0.425 | 0.340 | 0.985 | |||||

| Yes | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 33.00 ± 0.00 | 15.00 ± 0.00 | 15.00 ± 0.00 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | |||||

| No | 17.03 ± 4.45 | 29.73± 5.54 | 20.90 ± 7.16 | 18.23 ± 3.27 | 9.03 ± 1.69 | |||||

| Grok3 | 0.036 | 0.482 | 0.061 | 0.294 | 0.723 | |||||

| Yes | 12.50 ± 3.41 | 28.00 ± 5.94 | 14.50 ± 1.29 | 16.50 ± 1.29 | 8.75 ± 0.95 | |||||

| No | 17.40 ± 4.25 | 30.11 ± 5.47 | 21.62 ± 7.18 | 18.37 ± 3.42 | 9.07 ± 1.75 | |||||

| Participation in AI workshops | 0.162 | 0.261 | 0.172 | 0.124 | 0.038 | |||||

| Yes | 15.68 ± 4.33 | 28.75 ± 4.31 | 19.00 ± 5.21 | 17.25 ± 2.48 | 9.62 ± 1.50 | |||||

| No | 17.93± 4.38 | 31.00 ± 6.45 | 22.53 ± 8.53 | 19.06 ± 3.80 | 8.40± 1.63 | |||||

| Participation in AI educational courses | 0.074 | 0.037 | 0.199 | 0.144 | 0.765 | |||||

| Yes | 14.55 ± 3.94 | 26.66 ± 5.50 | 18.11 ± 5.64 | 16.77 ± 1.85 | 8.88 ± 1.69 | |||||

| No | 17.68 ± 4.37 | 31.13 ± 5.03 | 21.77 ± 7.55 | 18.68 ± 3.59 | 9.09 ± 1.68 | |||||

| Experience | 0.439 | 0.812 | 0.702 | 0.782 | 0.615 | |||||

| 1 - 5 | 16.00 ± 5.04 | 28.22 ± 7.51 | 20.66 ± 10.34 | 18.88 ± 4.53 | 8.44 ± 2.18 | |||||

| 6 - 10 | 18.50 ± 3.37 | 30.80 ± 3.11 | 23.10 ± 4.86 | 18.60 ± 2.75 | 9.10 ± 1.59 | |||||

| 11 - 15 | 17.20 ± 4.20 | 29.80 ± 5.58 | 19.20± 5.63 | 17.40 ± 1.14 | 9.40 ± 1.34 | |||||

| 16 - 20 | 14.33 ± 5.20 | 31.16 ± 6.11 | 19.00 ± 6.48 | 16.83± 3.54 | 9.16 ± 1.16 | |||||

| 20 - 36 | 19.00 ± 0.00 | 27.00 ± 0.00 | 15.00 ± 0.00 | 18.00 ± 0.00 | 11.00 ± 0.00 | |||||

| Rank | 0.395 | 0.480 | 0.352 | 0.665 | 0.696 | |||||

| Instructor | 17.00 ± 4.24 | 30.07 ± 5.70 | 21.10 ± 7.15 | 18.21 ± 3.32 | 9.07 ± 1.69 | |||||

| Assistant Professor | 14.66 ± 6.65 | 27.66 ± 2.08 | 17.00 ± 7.00 | 17.33 ± 3.21 | 8.66± 1.52 | |||||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; AI, artificial intelligence.

5. Discussion

As shown by the findings of this study, the professors’ level of knowledge in the field of AI is at a moderate level, and they had no significant differences with certain demographic variables, such as gender, work experience, and academic rank. This result aligns with the Hamedani et al.’s study and Saleh et al.’s study, which reported demonstrated a moderate level of AI knowledge among nurses and nursing students (13, 17). Additionally, the similarity of the results with the results of Kharroubi et al.’s study in Lebanon, which reported that only 43% of participants had a high level of knowledge, demonstrates the existence of a similar educational gap in the region’s countries (18). However, our finding of no significant correlation between gender and knowledge is also consistent with the results of Serbaya et al.’s study in Saudi Arabia, in which no significant difference was observed based on gender (19). Our findings are also in line with the results of Esfandiari et al.’s study, which also reported the physicians’ knowledge at a moderate level, and mentioned no significant difference between demographic groups (20).

In terms of attitude, the professors held positive but moderate attitudes toward AI. This finding aligns with the findings of Swed et al.’s study, which reported that 69.5% of participants had positive attitudes (21); with the findings of Kharroubi et al.’s study, which reported that more than half of the participants had positive attitudes; and with the findings of Hasan et al.’s study (13), which reported that 65% of participants had positive attitudes toward these technologies (18). In this regard, in a systematic review, Amiri et al. also reported a generally positive attitude among students and experts, noting ethical concerns and reduced patient interaction as limiting factors, also observed in the present study (22). The current study findings are also consistent with Esfandiari et al.’s study, which reported physicians’ attitudes as positive but not absolutely high (20). Concurrently, unlike Wang et al.’s study, which found age and gender to be influential factors on attitudes, no relationship with gender was observed in our research (23).

When it comes to application, professors made little use of AI tools. This finding is consistent with Abd El-Maksoud’s study, which reported the poor performance of users without formal education and highlighted the necessity of training (24). Similarly, our research findings align with those of Esfandiari et al.’s study, revealing that the practical use of these tools by physicians was also low due to a lack of education and insufficient familiarity (20). The negative impact of using certain platforms, such as DeepSeek and Grok3, on knowledge and application scores is also a finding that has been less frequently reported in similar studies and may stem from different choices in the use of AI tools.

In the realm of benefits, the highest agreement among professors belonged to increased speed of service delivery and improved access to vast patient databases, which is similar to the findings of studies conducted by Swed et al., Al-Qerem et al., and Esfandiari et al. (20, 21, 25). Concerns were primarily focused on privacy protection (83.9%) and reduced physician-patient interaction, which aligns with the findings of studies conducted by Serbaya et al., Esfandiari et al. (2024), and Pandya et al. (7, 19, 26).

This study is not without limitations. First, it relied on self-reported questionnaires, which are prone to response bias; for example, participants’ perceived need to demonstrate competence in artificial intelligence may have shaped their responses. Second, the study sample was drawn from a single university of medical sciences, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings to other institutions and nursing student populations in different regions or countries. Conducting future research with larger and more diverse samples, as well as interdisciplinary comparisons, can help better generalize the results and identify factors influencing knowledge, attitudes, and application of AI.

5.1. Conclusions

This research provides a clear picture of the current state of using AI at the School of Nursing, Abadan University of Medical Sciences. The present study findings reveal that while nursing professors at Abadan University of Medical Sciences hold relatively positive attitudes toward AI and have relative familiarity with common AI tools, such as ChatGPT, the actual application of this technology remains limited. Despite the high potential of AI to enhance the quality of education and research, ethical concerns and privacy protection issues continue to be raised as key barriers. Hence, it is recommended that targeted and structured educational programs be designed and implemented focusing on enhancing professors’ practical knowledge and skills in the field of AI. In addition to introducing the capabilities and applications of AI, these programs must also address ethical concerns and protect patient privacy. A revision of the content of formal courses and workshops is essential to enhance effectiveness and mitigate potential negative effects on attitudes. Moreover, providing supportive platforms and easy access to credible AI tools can elevate motivation and the practical ability to use this technology among professors. Targeted investment in AI education, policymaking, and infrastructure can culminate in flourishing this technology’s potential capacities and shaping a smarter future in academic settings.

5.2. Highlights

Moderate levels of knowledge and positive yet cautious attitudes toward artificial intelligence among nursing professors • Limited actual application of AI tools in educational and research activities • Highest perceived benefits related to faster service delivery and improved access to large patient databases • Main concerns focused on patient privacy, ethical issues, and confidentiality risks • Positive correlations between knowledge, attitude, application, and perceived benefits of AI Lay Summary This study explored how nursing professors at Abadan University of Medical Sciences view artificial intelligence (AI)—its benefits, challenges, and application. The study showed that while most professors are familiar with AI tools and hold generally positive attitudes toward their potential, their actual use of these technologies in teaching and research remains low. Many participants believed AI could speed up healthcare services and improve access to medical data, but they were also concerned about issues such as confidentiality and loss of the human touch in patient care. Overall, the findings highlight a need for targeted training programs, ethical guidelines, and institutional support to responsibly integrate AI into education and clinical practice.