1. Background

Educational simulators are essential tools in dental education, as they use physical models or virtual reality (VR) to create more realistic learning conditions and facilitate the transfer of concepts to real-world practice. Simulation not only facilitates the learning process but also contributes to improving performance, maintaining patient safety, and enhancing students’ critical thinking skills. While dental education is traditionally based on clinical encounters with patients, the risks associated with training errors may compromise patient health. Extracted teeth have long been used as educational tools in the preclinical curriculum; however, they present several challenges, including limited availability, lack of hygiene, variability in hardness, and inequities in the assessment of students’ performance. Therefore, the primary goal of dental education should be to ensure patient safety and well-being.

The concept of dental simulation was first introduced in 1894 by Oswald Fergus, who designed the 'phantom head' simulator (1). Numerous studies have confirmed the gradual advancements in this field and the necessity of using such simulators. In recent years, they have become part of the broader spectrum of virtual technologies applied in dental education. Virtual technologies have also been shown to enhance learning outcomes, particularly in areas such as endodontics, prosthodontics, and restorative dentistry. They encompass a wide range of applications, including VR simulation, haptic simulators, augmented reality devices, and real-time digital mapping for dental education (2, 3).

The VR simulators have been used as tools for manual skill training and feedback, and they have been shown to be beneficial for long-term learning among students during clinical exposure, in preclinical stages, and for those with limited access to patients (4). The VR is a technology that creates simulated environments in which users feel as though they are present in a real setting. The VR technology is founded on three key principles, namely immersion, interaction, and user engagement within the virtual environment. Immersion reflects the sense of presence within the virtual environment, while interaction represents the corrective actions performed by the user (5)

To experience VR, specialized head-mounted displays (HMDs) are commonly used. These devices allow users to view and interact with the virtual environment. Some headsets are standalone and do not require external hardware, whereas others must be connected to a computer or console. The VR simulators can present the oral and dental anatomy in a three-dimensional virtual format and serve as suitable alternatives to traditional teaching models, enabling students to thoroughly examine oral and dental structures (6). The use of VR in dental education provides an interactive and three-dimensional learning experience, increases student engagement and participation in the learning process, and enhances the overall quality of education (3).

The VR simulators make it possible to train in various dental surgeries and treatment procedures. These tools allow students to practice their skills in a simulated and safe environment and to learn from their mistakes (7). The primary aim of this study is to determine the effect of using the DentaSim VR simulator (developed by SiMedix) in preclinical endodontic training for undergraduate dental students.

2. Objectives

1. Evaluate the effect of using the DentaSim VR simulator (developed by SiMedix) on the competency of undergraduate dental students in preclinical endodontic training.

2. Compare the performance of students trained with the VR simulator and those trained with conventional methods in access cavity preparation of maxillary central teeth.

3. Assess the impact of VR training on the occurrence of critical errors, including perforation, gouging, and canal accessibility.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was conducted as a comparative case-control study. Forty fourth-year undergraduate dental students enrolled in the endodontic fundamentals course were included. Before beginning the practical exercises, the principles and theories regarding the preparation of access cavities for maxillary central teeth were presented, and a theoretical entry test (pass/fail) was administered to assess eligibility for the practical phase. One student was excluded due to failing the test, leaving 39 eligible participants. These 39 students were then randomly assigned to two groups, with 20 in the experimental group (VR group) and 19 in the control group (conventional group).

3.2. Practical Exercises

The practical exercises were carried out over three sessions. In the first session, both groups received an explanation and a demonstration of access cavity preparation for maxillary central teeth, followed by a pre-test. All pre- and post-tests in both groups were performed on resin typodont teeth. In the second session, the VR group practiced independently with the VR simulator for two hours without instructor supervision, and immediately afterward, the first post-test (on resin typodont teeth) was administered. During the same session, the control group practiced for two hours on extracted teeth under instructor supervision, submitted their work, and then completed the first post-test (on resin typodont teeth). In the third session, both groups performed complementary practice for two hours on extracted teeth under instructor supervision, after which the second post-test (on resin typodont teeth) was conducted. Thus, the total training volume in the control group consisted of four hours of practice on extracted teeth, whereas in the VR group it was a combination of two hours with the simulator and two hours on extracted teeth.

3.3. Evaluation Criteria

The evaluation criteria for access cavity preparation of maxillary central teeth (Table 1) were determined based on a literature review and expert opinion, and were provided to the examiners in the form of a standardized checklist (8-10). Prior to the evaluation, three expert faculty members independently rated the importance of each criterion on a predefined scale ranging from 1 to 3, and the average of their ratings was assigned as the weight of each criterion (Table 2). All test samples were assessed in a single-blind manner. Three independent examiners, using proper magnification and illumination along with a periodontal probe, visually examined the prepared samples. For each criterion, they selected one of the following performance levels: Very poor (0), poor (1), inadequate (2), acceptable (3), good (4), or excellent (5). Inter-rater reliability was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.866. For each participant, the mean score from the three examiners was first calculated for each criterion, and then the overall score was obtained as the sum of the products of these means multiplied by the corresponding weights. In addition, three specific criteria (perforation, gouging, and canal accessibility) were designated as critical. If a prepared sample scored below “acceptable” (score < 3) on any of these critical criteria, it was classified as “unacceptable” overall, even if high scores were achieved in other areas. This procedure was implemented to prevent the acceptance of errors with potential clinical consequences.

| Evaluation Criterions | Correct Method | Incorrect Method |

|---|---|---|

| Perforation a | Adequate extension of the access cavity toward the incisal wall without perforating the labial wall during preparation | Perforation of the labial wall during access cavity preparation |

| Gouging a | Opening of the pulp chamber floor only along the crown-root path | Labial gouging; mesial gouging; distal gouging |

| Canal accessibility a | The cavity preparation should provide direct access and visibility into the canal. | Instruments are inserted at an angle into the canal, or there is no direct visibility into the canal. |

| Outline form of the access cavity | The outline form should be free of sharp angles, and in maxillary central teeth it should present as a rounded triangular shape with the base oriented toward the incisal edge. | Not in the form of a rounded triangle, with sharp angles present |

| Removal of the lingual shoulder | Excessive dentin removal from the lingual wall of the pulp chamber | Remaining lingual shoulder |

| Removal of the pulp horn | Complete removal of the pulp horn | Remaining part of the pulp horn |

| Complete removal of the pulp chamber roof | Clear access pathway with complete removal of the pulp chamber roof | Remaining part of the pulp chamber roof |

| Convergence of the mesial and distal walls toward the cingulum | Presence of convergence of the mesial and distal walls toward the cingulum | Lack of convergence of the walls toward the cingulum |

| Adequate extension of the cavity toward the incisal edge | Adequate extension of the cavity toward the incisal edge | Inadequate extension of the cavity toward the incisal edge |

a The vital errors by which the student can fail.

| Criterions | Mean Weight | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perforation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Gouging | 2.3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Canal accessibility | 2.6 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Outline form of the access cavity | 2.3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Removal of the lingual shoulder | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Removal of the pulp horn | 1.6 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Complete removal of the pulp chamber roof | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Convergence of the mesial and distal walls toward the cingulum | 1.3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Adequate extension of the cavity toward the incisal edge | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

3.4. Equipment

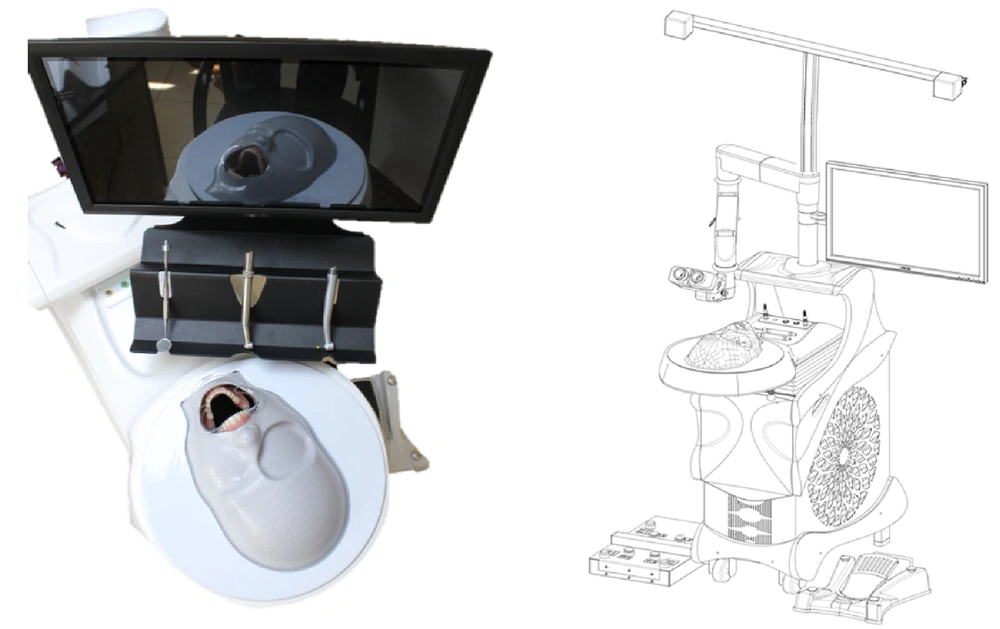

The equipment utilized in this study included resin typodont teeth manufactured by SiMedix (Tehran, Iran) and high-speed rotary instruments with diamond burs (Figure 1). In addition, the DentaSim VR-based educational system, developed by SiMedix, was used (Figure 2). This simulator is equipped with a motion capture system with an accuracy of 50 microns, which records the user’s hand movements and transmits them to the computer. Within the processor, the interaction between the simulated instrument and the virtual dental models is calculated, then processed by the graphics processor and displayed to the user through the VR headset.

3.5. Virtual Reality Training Exercises

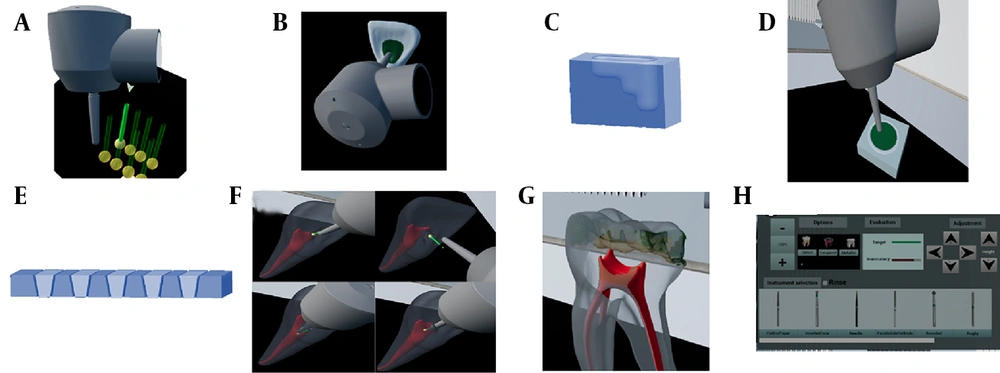

Focusing on access cavity preparation for maxillary central teeth, the VR group performed exercises aimed at improving turbine handling, neuromuscular coordination, understanding tooth anatomy, mastering the correct bur angulation, and reinforcing acquired knowledge (Figure 3).

Training modules shown in panels A - H: A, vertical hand-tremor exercise; B, targeted access-cavity preparation for maxillary central; C, depth-control exercises; D, geometric-shape drilling; E, wall-angulation and cutting practice; F, advanced tremor-control exercise specific to maxillary central endodontics; G, transparent-tooth view (cavity-pulp relationship); and H, in-simulator scoring interface.

- Hand tremor exercise: Hand tremor during vertical movements is measured and improved. This exercise applies to restorative cavities, endodontic access cavities, and wall shaping in prosthodontics.

- Preparation of simple geometric shapes: Participants first practice shaping simple forms before addressing complex structures, to understand the principles of cavity preparation.

- Preparation of simple patterns: Training includes cavity depth and wall convergence/divergence. A separate exercise focuses solely on cavity wall angles, enabling participants to master correct instrument positioning.

- Cavity preparation with marked targets: Participants cut only within designated areas, becoming familiar with the proper cavity form, correct hand-piece control, and pulp/tooth anatomy.

- Guided cavity preparation exercise: Using a guide, participants follow a correct cavity outline. This improves understanding of the final cavity form, though over-preparation or deviation may occur.

- Advanced hand tremor exercise for endodontics: Participants practice reducing tremor and maintaining correct turbine positioning. Step-by-step access preparation is guided by a predefined path.

3.6. Supportive Features During Training

Technology provides opportunities that were not previously available. For example, during training, participants can activate a transparent tooth view to observe the relationship between the prepared cavity and the pulp, helping to prevent perforation during treatment. This method also makes it much easier to assess gouging. In addition, image magnification, while preserving the real dimensions of hand movements, allows users to observe preparation details more clearly. Scores at each stage, along with visual and auditory feedback on errors, play a crucial role in the effectiveness of the educational system.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and visual inspection of histograms and Q-Q plots. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (percentages), and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were conducted using the independent t-test (or Mann–Whitney U test for non-normal data), and categorical variables using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Within-group changes were evaluated with the paired t-test. A 95% confidence interval was applied, and significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0.

4. Results

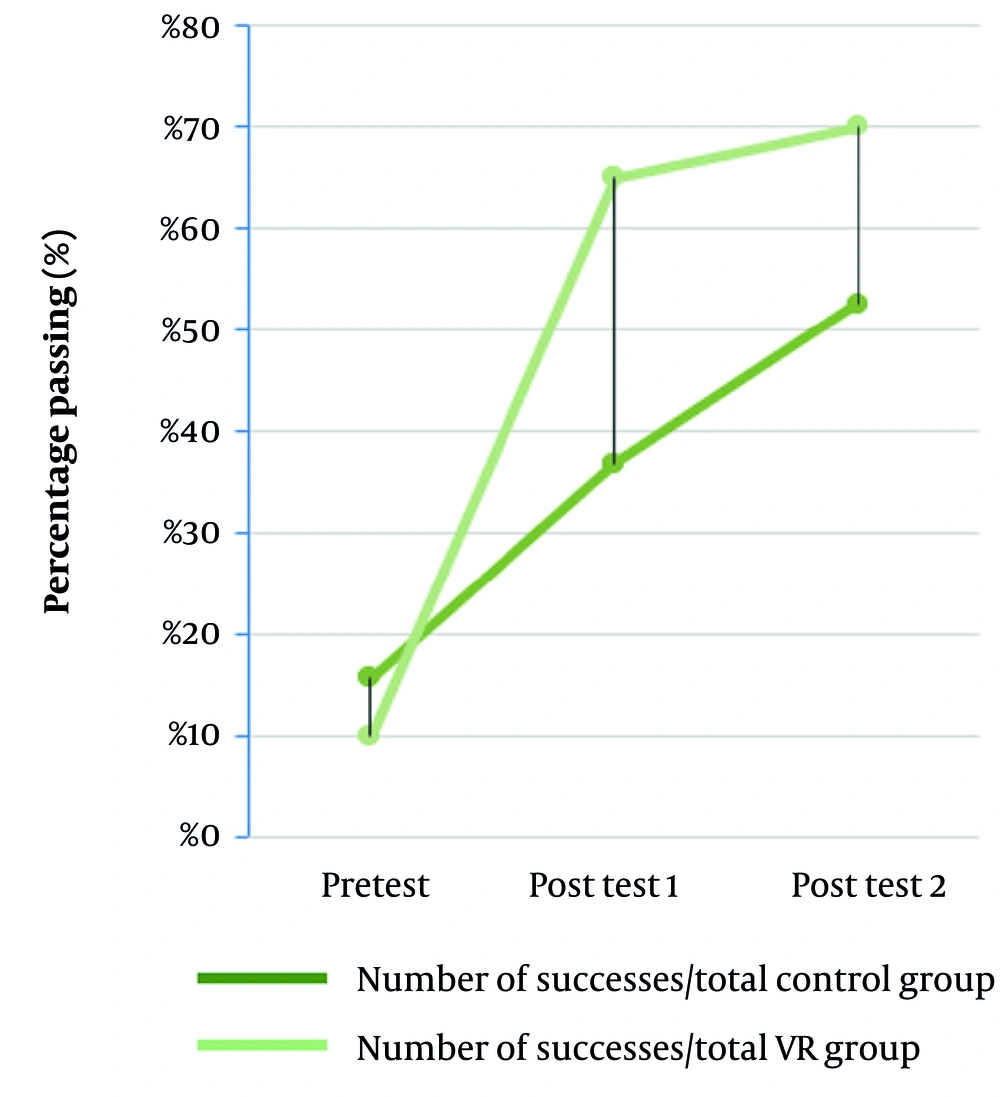

For each participant, the overall score was calculated based on the weighted mean of the criterion scores (Table 2). The overall scores for each test in both groups are presented in Table 3. The pass/fail status of each participant was determined according to the same weighted mean of the criteria (Table 2), with consideration of the critical criteria. The percentage of successful participants in each group and in each test is shown in Figure 4. As illustrated in Figure 4, the pass rate in the first session differed substantially between the control group (C) and the VR group, and overall, the total pass rate was higher in the VR group (Table 4).

| Groups; Participant Number | Pre-test | Post-test 1 | Post-test 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | |||

| 1 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.8 |

| 2 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| 3 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| 4 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| 6 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| 7 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| 8 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| 9 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.9 |

| 10 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.2 |

| 11 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 3.7 |

| 12 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| 13 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| 14 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| 15 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| 16 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| 17 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

| 18 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 4.1 |

| 19 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.6 |

| VR | |||

| 20 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| 21 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| 22 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 4.8 |

| 23 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 4.2 |

| 24 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 4.3 |

| 25 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| 26 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.4 |

| 27 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| 28 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| 29 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.8 |

| 30 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| 31 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| 32 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| 33 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| 34 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| 35 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| 36 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| 37 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| 38 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| 39 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.1 |

Abbreviations: C, control group; VR, virtual reality.

| Groups | Number of Successes | Percentage of Successes Relative to the Total Sample (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | VR | C | VR | |

| Pre-test | 3 | 2 | 16 | 10 |

| Post-test 1 | 7 | 13 | 37 | 65 |

| Post-test 2 | 10 | 14 | 53 | 70 |

| All | 19 | 20 | - | - |

Abbreviation: C, control group; VR, virtual reality.

Analyses were reported separately for within-group and between-group comparisons. The within-group results showed that the first session led to a significant improvement in scores in both groups (P < 0.05). In the second session, no significant progress was observed in most of the criteria in either group. A comparison of changes between the first and second post-tests revealed statistically significant differences in only 2 out of the 8 criteria (Table 5). Specifically, in the first session, the control group showed significant improvement in 5 out of 8 criteria, whereas the VR group demonstrated significant improvement in all 8 criteria (Table 6). These findings highlight the effectiveness of simulator-based training in enhancing participant performance.

| Groups | Paired Differences | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference (Lower - Upper) | ||

| C | |||

| Perf | - | - | - |

| Gouging | -0.561 ± 1.307 | -1.192 - 0.069 | 0.078 |

| Canal access | -0.740 ± 1.105 | -1.273 - -0.208 | 0.009 |

| Access outline | -0.488 ± 0.803 | -0.875 - -0.100 | 0.016 |

| Ling. Shoulder | -0.498 ± 1.424 | -1.185 - 0.188 | 0.145 |

| Pulp horn | 0.196 ± 0.686 | -0.134 - 0.527 | 0.228 |

| PC roof | -0.091 ± 0.538 | -0.350 - 0.168 | 0.469 |

| MD-conv | -0.161 ± 0.660 | -0.480 - 0.157 | 0.301 |

| Inc extension | -0.088 ± 0.859 | -0.502 - 0.326 | 0.662 |

| Overall | 0.288 ± 0.360 | 0.114 - 0.462 | 0.003 |

| VR | |||

| Perf | - | - | - |

| Gouging | -0.500 ± 1.023 | -0.979 - -0.021 | 0.042 |

| Canal access | -0.250 ± 0.716 | -0.585 - 0.085 | 0.135 |

| Access outline | -0.383 ± 0.811 | -0.763 - -0.004 | 0.048 |

| Ling. Shoulder | -0.350 ± 0.791 | -0.720 - 0.020 | 0.062 |

| Pulp horn | -0.050 ± 0.987 | -0.512 - 0.412 | 0.823 |

| PC roof | 0.000 ± 0.911 | -0.426 - 0.426 | 1.000 |

| MD-conv | -0.183 ± 1.152 | -0.723 - 0.356 | 0.485 |

| Inc extension | -0.200 ± 0.994 | -0.665 - 0.265 | 0.379 |

| Overall | 0.212 ± 0.483 | -0.014 - 0.438 | 0.065 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; C, control group; VR, virtual reality.

a Paired samples test (pre-test-post-test 2).

| Groups | Paired Differences | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference (Lower - Upper) | ||

| C | |||

| Perf | - | - | - |

| Gouging | -0.904 ± 1.111 | -1.439 - -0.368 | 0.002 |

| Canal access | -0.646 ± 1.692 | -1.461 - 0.170 | 0.114 |

| Access outline | -0.447 ± 1.001 | -0.930 - 0.035 | 0.067 |

| Ling. shoulder | -0.986 ± 0.889 | -1.415 - -0.557 | 0.000 |

| Pulp horn | -0.539 ± 1.211 | -1.122 - 0.045 | 0.068 |

| PC roof | -0.619 ± 1.116 | -1.157 - -0.081 | 0.026 |

| MD-conv | -0.654 ± 0.906 | -1.091 - -0.218 | 0.006 |

| Inc extension | -0.861 ± 0.713 | -1.205 - -0.518 | 0.000 |

| Overall | 0.670 ± 0.447 | 0.455 - 0.886 | 0.000 |

| VR | |||

| Perf | - | - | - |

| Gouging | -1.865 ± 1.327 | -2.486 - -1.244 | 0.000 |

| Canal access | -1.192 ± 1.437 | -1.864 - -0.519 | 0.001 |

| Access outline | -1.577 ± 1.113 | -2.098 - -1.056 | 0.000 |

| Ling. shoulder | -1.385 ± 1.452 | -2.064 - -0.706 | 0.000 |

| Pulp horn | -1.143 ± 1.016 | -1.619 - -0.668 | 0.000 |

| PC roof | -1.162 ± 1.071 | -1.663 - -0.660 | 0.000 |

| MD-conv | -1.088 ± 1.206 | -1.653 - -0.524 | 0.001 |

| Inc extension | -1.383 ± 1.025 | -1.863 - -0.903 | 0.000 |

| Overall | 1.255 ± 0.658 | 0.947 - 1.563 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; C, control group; VR, virtual reality.

a Paired samples test (pre-test-post-test 1).

In the between-group comparison, no significant difference was observed in the pre-test; however, in both the first and second post-tests, the VR group performed significantly better, with differences noted in 6 out of 8 criteria (Tables 7 and 8). It should be noted that the perforation criterion was excluded from the final analyses due to the lack of notable changes across sessions. The critical criteria (perforation, gouging, and canal accessibility) were defined as events that result in overall treatment failure and are expected to decrease in occurrence throughout the training process.

| Variables | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference (Lower - Upper) | P-Value | |

| Gouging | -0.5711 ± 0.3343 | -1.2484 - 0.1063 | 0.096 |

| Canal access | -1.0482 ± 0.3423 | -1.7419 - -0.3546 | 0.004 |

| Access outline | -0.7228 ± 0.2099 | -1.1480 - -0.2976 | 0.001 |

| Ling. shoulder | -1.1772 ± 0.3651 | -1.9169 - -0.4375 | 0.003 |

| Pulp horn | -0.7500 ± 0.2496 | -1.2556 - -0.2444 | 0.005 |

| PC roof | -0.7886 ± 0.2717 | -1.3391 - -0.2381 | 0.006 |

| MD-conv | -0.5272 ± 0.2350 | -1.0033 - -0.0511 | 0.031 |

| Inc extension | -0.5377 ± 0.2814 | -1.1079 - 0.0325 | 0.064 |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

a Independent samples test.

| Variables | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference (Lower - Upper) | P-Value | |

| Gouging | -0.5096 ± 0.2872 | -1.0915 - 0.0722 | 0.084 |

| Canal access | -0.5579 ± 0.2092 | -0.9817 - -0.1341 | 0.011 |

| Access outline | -0.6184 ± 0.2492 | -1.1234 - -0.1134 | 0.018 |

| Ling. shoulder | -1.0289 ± 0.3512 | -1.7406 - -0.3173 | 0.006 |

| Pulp horn | -0.9965 ± 0.2264 | -1.4553 - -0.5377 | 0.000 |

| PC roof | -0.6974 ± 0.2064 | -1.1157 - -0.2791 | 0.002 |

| MD-conv | -0.5491 ± 0.3026 | -1.1623 - 0.0641 | 0.078 |

| Inc extension | -0.6500 ± 0.2656 | -1.1882 - -0.1118 | 0.019 |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

a Independent samples test.

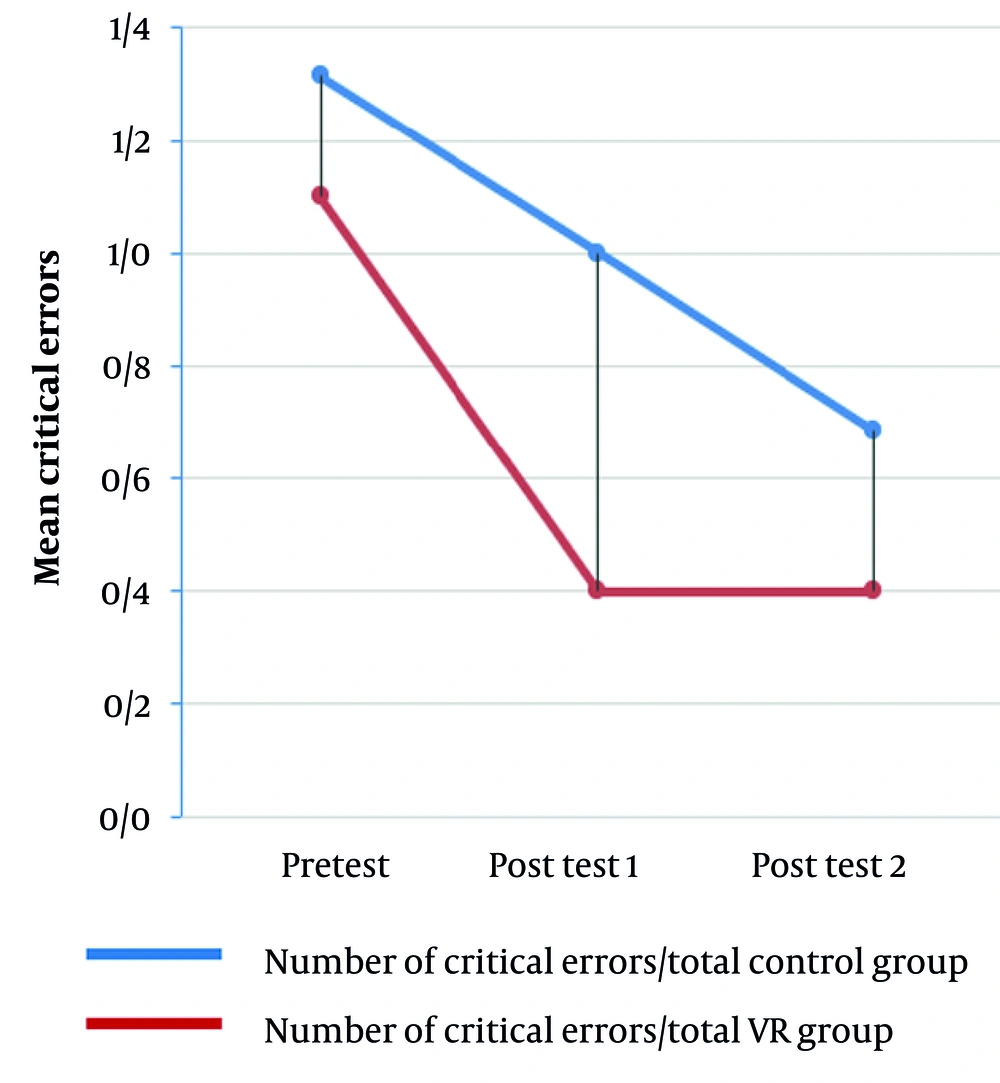

The mean critical error rates for both groups across the sessions are illustrated in Figure 5. As shown in the figure, the mean critical error rate in the VR group decreased markedly across the sessions. Continuing with conventional training in the VR group did not lead to further significant reductions in critical errors. However, a comparison of critical error occurrence between the two groups in different tests revealed that after the first session, the VR method had a significant effect on reducing critical errors, whereas after the second session no significant difference between the groups was observed. These findings suggest that the conventional method, when continued, may also be effective in maintaining the reduction of critical errors (Table 9).

| Tests | Mann-Whitney U | Wilcoxon W | Z | Asymp. P-Value (2-Tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 158.000 | 368.000 | -0.972 | 0.331 |

| Post-test 1 | 118.000 | 328.000 | -2.214 | 0.027 |

| Post-test 2 | 154.000 | 364.000 | -1.167 | 0.243 |

a Mann-Whitney test.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of using VR simulators on the competency of preclinical students in endodontic access cavity preparation. The main findings demonstrated that the VR group (training with the simulator) achieved greater overall improvement and a higher pass rate compared to the control group. In particular, during the first session, the VR group showed significant improvement in all criteria, whereas the control group improved significantly in only five criteria. This highlights the ability of the simulator to facilitate learning and accelerate the acquisition of fundamental skills. The present findings are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the role of high-technology simulators, including VR, in enhancing the quality of health professions education (11-14). This convergence of evidence is particularly notable in relation to accelerating learning and improving practical performance (15, 16).

Potential mechanisms that may explain these effects include the opportunity for deliberate practice, the provision of immediate feedback, and the application of micro-learning approaches, each of which contributes to targeted practice, rapid error correction, and the breakdown of skills into smaller components (17-20). In the current study, the simulator provided opportunities for deliberate practice and immediate feedback, which likely supported self-assessment and the prompt correction of student performance. However, the temporal pattern of improvement indicated that the accelerating effect of the simulator was more pronounced in the initial phase. In the second session, neither group showed significant progress in most criteria, and only two criteria demonstrated significant change. This pattern suggests that the immediate and substantial impact of simulation may diminish over time if not reinforced, highlighting the need for continuity and well-designed training sessions to consolidate skills.

Another clinically important finding was the reduction of critical errors in the VR group after the first session. The decrease in perforation, gouging, and canal accessibility issues may reflect a potential enhancement in the safety of student performance. On the other hand, continuing with conventional training in the VR group did not lead to further reductions in these errors, although the data suggest that conventional training, when continued, is also capable of reducing their occurrence. Therefore, the simulator may serve as an effective complementary tool in the early phases to accelerate safe learning (2, 21).

From an educational planning perspective, a practical advantage of using simulators is the reduced need for continuous instructor presence in the early phases, which can allow for the redistribution of educational resources and enable faculty to focus on more complex concepts. This advantage, however, requires the development of technical and instructional support mechanisms for faculty members to ensure that unfamiliarity with technology does not hinder effective implementation (22, 23). In addition, the diversity of platforms and the lack of a unified educational standard are factors that must be considered when generalizing the results (24).

The main limitations of this study include its single-center design and relatively small sample size, the need for faculty training and technical support prior to the widespread adoption of the technology, and variations in simulator fidelity. Future studies are therefore recommended to adopt multicenter designs with larger sample sizes, to develop training programs with technical support for familiarizing faculty members with VR technology, to investigate the optimal timing for integrating VR into the curriculum, and to conduct comprehensive economic evaluations comparing the costs and benefits of conventional versus simulator-based education.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that training with a VR simulator can enhance the effectiveness of preclinical education in access cavity preparation for endodontics compared with conventional methods. Therefore, VR may be regarded as a reliable complementary educational tool, although it cannot yet be considered a definitive substitute for traditional approaches. To ensure effective utilization of this technology, its purposeful integration into the curriculum is required, with clearly defined learning objectives and adequate instructional and technical support for faculty members. Finally, further multicenter, longitudinal, economic, and applied studies in other fields of dentistry (such as prosthodontics, implantology, and restorative dentistry) are essential to comprehensively determine the effectiveness, limitations, and cost-efficiency of this tool.

5.2. Highlights

Integration of VR simulation into preclinical endodontic training accelerates early skill acquisition, improves performance across key competencies, and reduces critical errors, particularly during initial learning sessions. Virtual reality provides safe, repeatable, and feedback-rich practice opportunities, enabling students to enhance precision, canal accessibility, and hand stability without requiring continuous instructor supervision. Incorporating VR as a complementary tool within dental curricula—supported by clear educational objectives and technical guidance—can optimize resource allocation, enhance patient-safety–oriented skill development, and support future expansion into other dental disciplines.

5.3. Lay Summary

In this study, we looked at whether a VR simulator could help dental students learn how to prepare access cavities in endodontics more effectively. We compared students who practiced with the VR simulator to those who trained using traditional methods. The results showed that students using VR improved faster, made fewer important mistakes, and felt more confident in the early stages of learning. Virtual reality allowed them to practice safely, repeat steps as needed, and receive instant feedback. Although VR cannot replace traditional training, it can be a valuable extra tool to support students and help them learn essential skills more quickly and safely.